Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

The Wench Is Dead

Book by Colin Dexter From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

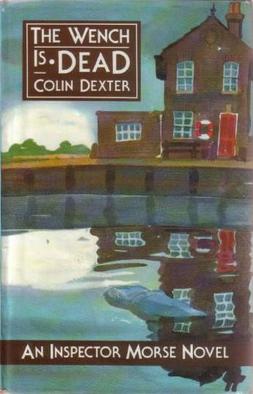

The Wench Is Dead is a historical crime novel by Colin Dexter, the eighth novel in the Inspector Morse series. The novel received the Gold Dagger Award in 1989.

Remove ads

Plot summary

Summarize

Perspective

Inspector Morse is admitted to the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford with a perforated ulcer. Early the next morning, another patient in the same ward, Colonel Wilfred Deniston, dies. In the evening, Morse is visited by Detective Sergeant Lewis, who brings him two books to read: a study of crime and punishment in mid-19th-century Shropshire (chosen by Mrs Lewis) and a salacious paperback titled The Blue Ticket (chosen by Lewis himself). Later, Colonel Deniston's widow gives Morse a booklet written by Deniston and titled Murder on the Oxford Canal, about a 19th-century murder case.

Morse reads Deniston's book (the text of which, divided into four parts, is reproduced in full over the course of the novel). It tells the story of the death in 1859 of 38-year-old Joanna Franks, who was found drowned in the Oxford Canal at Duke's Cut, close to Oxford. She had been a passenger on the "fly" boat Barbara Bray, travelling from Liverpool to join her husband, Charles Franks, an ostler, who had obtained a new job in London. The boat's crew comprised Jack 'Rory' Oldfield, the captain; Alfred Musson (alias Brotherton); Walter Towns (alias Thorold); and a "boy", Thomas Wootton. All four were charged with Franks' rape and murder. The charges against Wootton were dropped, but Oldfield, Musson and Towns were found guilty and sentenced to death. Towns received a last-minute reprieve and was transported to Australia, but Oldfield and Musson were publicly hanged. As Morse reads, he develops doubts about the evidence presented at the trial, and the soundness of the verdict.

He seeks additional information through Lewis, who is sent in search of the original assize court registers; and through Christine Greenaway, the daughter of another patient on the ward, who works at the Bodleian Library, and is sufficiently taken with Morse to pursue research on his behalf at the Westgate Central Library. Lewis discovers that some of the physical evidence from the Franks case is still held at the City Police headquarters on St Aldate's, including Joanna Franks' shoes and knickers.

Morse is sent home from hospital, but is told to take a further two weeks off work. He continues to ponder the Franks case. He theorises that Joanna had not been drowned at all, but had staged her death as part of an insurance fraud (her father had been an agent for an insurance company), substituting another body for her own. He further speculates that the supposed death in 1858 of her first husband, F. T. Donovan, a stage conjuror, might have been a similar fraud. He decides to visit Donovan's grave in Ireland, where, with the help of a local police officer, Inspector Mulvaney, he carries out an unauthorised exhumation. Donovan's coffin proves to contain only a carpet rolled around some squares of peat. Morse and Lewis then visit the terraced house in Derby that had been Joanna's childhood and pre-marital home, and is now about to be demolished. Inside, under multiple layers of wallpaper, they discover a set of marks recording Joanna and her brother's heights as they grew up: these confirm that Joanna had been considerably shorter than the body found in the canal. In an epilogue, Morse abruptly realises that the name of Donald ("Don") Favant, a passer-by and potential witness in the case who subsequently disappeared, was an anagram of F. T. Donavan: he must have been Donovan using a pseudonym.

Remove ads

Title

The title of the novel comes from Christopher Marlowe's play The Jew of Malta; the following quotation serves as the epigraph to the novel:

Friar Barnardine. Thou hast committed –

Barabas. Fornication: but that was in another country;

And besides, the wench is dead.

T. S. Eliot used the same quote as an ironic prologue to his poem "Portrait of a Lady".

Inspiration

Summarize

Perspective

Dexter based the novel on the 1839 murder of 37-year-old Christina Collins as she travelled the Trent and Mersey Canal at Rugeley, Staffordshire, on the Staffordshire Knot en route to London.[1] Of the four crewmen, captain James Owen and boatman George Thomas were hanged for the murder by William Calcraft and assistant George Smith, while boatman William Ellis was transported for his involvement (following a last minute reprieve from his death sentence), and cabin boy William Muston was not charged.[1] The evidence was largely circumstantial: the three accused were drunk at the time of the woman's death, numerous witnesses attested to Collins being distressed as the men used sexually explicit language towards her, and all four men (including the cabin boy) were seen to have lied in court in an attempt to pin the blame on each other and to escape punishment.[1] The three accused stated that Collins jumped into the canal of her own accord and drowned, despite the fact that the water at the particular section of the canal was less than four feet in depth.[1] Alan Hayhurst, author of the 2008 book Staffordshire Murders, states that "this author does not agree with Mr Dexter's conclusions!"[1]

According to the dedication to the novel, it was Harry Judge, a "lover of canals", who introduced Dexter to the small book The Murder of Christina Collins by John Godwin, a local historian and former headteacher in Rugeley. The booklet gives many details of Christina’s early life and the criminal trial that followed her murder.

Much of the research for the novel was carried out at the William Salt Library in Stafford. Dexter recalls that he spent "a good many fruitful hours in the library" consulting contemporary newspaper reports of Christina's murder.[2]

The novel's framing device, of a detective solving an historical murder while laid up in hospital, was most famously used by the mystery novelist Josephine Tey in her 1951 novel, The Daughter of Time – in that case, the murder of the Princes in the Tower.

Remove ads

Awards and nominations

The Wench Is Dead won the British Crime Writers' Association Gold Dagger Award for the best crime novel of the year in 1989.

Adaptations

Summarize

Perspective

The novel was filmed as an episode in Inspector Morse and was first aired on 11 November 1998. The filming took place on the Grand Union Canal at Braunston locks, south of Braunston Tunnel and on the Kennet and Avon Canal, all broad canals, whereas the Oxford Canal is a narrow canal. The historical office and loading scenes were filmed at the Black Country Museum in Dudley. The Barge Inn at Honeystreet, Vale of Pewsey, Wiltshire, was used in many scenes and pictures from the filming are on their website.[3] The boats were provided by South Midland Water Transport. Barbara Bray is actually Australia, built in 1894 by Fellows Morton & Clayton. Trafalgar was Northolt built in 1899 by the same firm. Fazeley built in 1921 is also used but carries two names. Three motor boats (Archimedes, Clover and Jaguar) were used to tow the unpowered horse boats around the country to the various locations which involved a two-week trip.[4] The adaptation kept the details of the historic mystery virtually identical, but the present day sections introduced a number of confidantes for Morse, the book's author Dr Van Buren (portrayed by Lisa Eichhorn), Adele Cecil (a character from the adaptation of Death is Now My Neighbour) and Detective Constable Adrian Kershaw (played by Matthew Finney), a replacement for Lewis who is absent from the television version. It also guest starred Paul Mari as Rory Oldfield, Alan Mason as the consultant and Aline Mowat as Sister Nessie.

A BBC Radio 4 play The Wench Is Dead, dramatised by Guy Meredith, was broadcast in 1992 starring John Shrapnel as Morse and Robert Glenister as Lewis, with Garard Green as Col. Deniston, Joanna Myers as Christine Greenaway, Peter Penry-Jones as Waggy Greenaway, and Kate Binchy as Sister MacLean. The play was directed by Ned Chaillet.[5]

Remove ads

Publication history

- 1989, London: Macmillan ISBN 0-333-51787-3, Pub date 26 October 1990, Hardback

- 1990, New York: St. Martin's Press ISBN 0-312-04444-5, Pub date May 1990, Hardback

- 1991, New York: Bantam ISBN 0-553-29120-3, Pub date 1 May 1991, Paperback

- 1991, London: Pan ISBN 0-330-31336-3, Pub date 12 July 1991, Paperback

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads