Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

People's Court (Germany)

Instrument of judicial murder in Nazi Germany From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The People's Court (German: Volksgerichtshof pronounced [ˈfɔlksɡəˌʁɪçt͡shoːf] ⓘ, acronymed to VGH) was a Nazi tribunal established in 1934 to try political crimes such as treason. It became one of the most notorious instruments of state terror in the Third Reich, and is associated with summary justice, execution, and denial of civil and legal rights.

The court was created on 24 April 1934, in response to acquittals in the Reichstag fire trial, and building on precedents such as the Bavarian People's Court. Based on factors such as the stab-in-the-back myth, the Enabling Act, and the Führerprinzip, the court aimed to impose severe penalties on the Nazis’ enemies under a facade of legality.

Initially the court maintained some semblance of legal procedure but progressively abandoned all pretense of independence. During the 1936-1942 presidency of Otto Georg Thierack the court expanded its jurisdiction and openly declared itself a political weapon. With the start of World War II, prosecutions grew exponentially, and as the war turned against Germany sentences grew harsher, with the execution rate jumping from 5% to 46% under Judge-President Roland Freisler. After Freisler's death in an air raid, the court continued under Harry Haffner before dissolving in April 1945.

The People's Court rejected liberal legal principles, including judicial independence, due process, the right to appeal, and the right to counsel. It also operated on the principle of punishing "criminal mentality" rather than crimes defined in law and used a broad interpretation of “preparation for treason” to impose the death penalty for acts such as telling anti-Nazi jokes and listening to foreign radio stations.

Between 1937 and 1945, the court heard over 14,000 cases, executing over 5,000 people. Victims included resistance members, communists, and those considered disloyal to the Nazi regime. The 1944 show trials of the participants in the plot to kill Adolf Hitler are infamous for Freisler’s attempts to berate and humiliate the defendants.

After the war, most People's Court judges escaped justice, and at least 29 People's Court judges and 69 prosecutors went on to work in the West German court system. However, in 1985, the West German Bundestag declared that the People's Court was an instrument of judicial murder and state terrorism, stating "The Volksgerichtshof was an instrument of state-sanctioned terror, which served one single purpose, which was the destruction of political opponents. Behind a juridical facade, state-sanctioned murder was committed", and in 1998 all judgments of the People’s Court were annulled by German Federal Law.

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

Background

H.W. Koch states that three main features of Germany's history led to the creation of the People's Court:[1]

- The Stab-in-the-back myth that Germany had lost World War I primarily because of treason and revolution on the home-front.

- The Enabling Act which empowered the government to deviate from the constitution without any legislative constraints.

- The Führerprinzip, the belief that Germany's leader, Adolf Hitler, was both above the law and deserving of unquestioning loyalty.

In addition, whilst Hitler disliked laws and lawyers as a constraint on his freedom of action, he was also concerned to keep up a facade of legality to his actions, a process now known as autocratic legalism. He openly stated that, "we take recourse to democratic means only to win power," and that "what forces us to use such means is the constitution".[2]

Previous special courts

Political courts existed in Germany before the Nazi era, and Robert D. Rachlin argues that the excesses of the People's Court can be viewed in the context of historical antecedents such as the medieval Feme Courts and the reactionary, anti-democratic and anti-semitic Weimar Republic judiciary that treated right-wing and anti-Jewish crimes more leniently than they treated similar crimes which were committed by members and supporters of the political left.[3] Previous Sondergericht (special court) and Volksgerichte (people's court) had generally been set up temporarily in response to civil disturbances. For example, the People's Courts of Bavaria were established during the German Revolution in November 1918 and handed out more than 31,000 sentences before being abolished in May 1924. One of the Bavarian People's Court's most notable trials was that of the Beer Hall Putsch conspirators.[4]

Nazi expansion of treason laws

Under the Weimar Constitution, Articles 80–92 of the 1871 Reichsstrafgesetzbuch (Federal Penal Code), defined high treason as attacks on the head of state, attempts to alter the territory of the federal state, or violations of the constitution. The Nazis, regarded this definition as excessively liberal and too narrow.[5] The day after the Reichstag fire of 27 January 1933, they enacted two decrees expanding the law on treason: the ‘Decree of the President against Treason and High Treasonous Activities’, which extended the definition of treason to include "acts of political subversion”, and the ‘Decree of the President for the Protection of People and State’, commonly known as the Reichstag Fire Decree, which made all acts of treason capital offences.[6]

A month later, in a 23 March 1933 speech to the Reichstag regarding the Enabling Act, Hitler prefigured the creation of the People's Court with his statement that, "Not the individual, but the Volk must be the focus of legal concern... In the future, state and national treason will be annihilated with barbaric ruthlessness".[7]

Establishment

The People's Court was established on 24 April 1934 by decree of Reich Chancellor Adolf Hitler.[8] The proximate cause of its creation was the outcome of the Reichstag fire trial in front of the Reich Court of Justice (Reichsgericht) in which all but one of the defendants were acquitted.[9] However, Hitler had pronounced the necessity for a "national tribunal" to execute "tens of thousands" of people he regarded as traitors in Mein Kampf.[10]

The ‘Law Amending Provisions of Criminal Law and Criminal Procedure’ which created the People’s Court also transferred jurisdiction over crimes that had previously been within the jurisdiction of the Reich Court of Justice: treason, high treason, major cases of sabotage, and assassination of members of the government.[10] The definition of treason used by the court was initially unchanged, but the penalties were made substantially more severe.[8] The same law defined the composition of the court, the appointment of its members, and many of its procedures.[11]

Criticism of the creation of the People's Court was countered by statements that it was a temporary expedient and would either be replaced or transformed as part of future reforms of the legal system. Official commentary saw the court only as a way to make law enforcement more efficient.[12]

The first president of the court was a former judge of the Berlin Special Court, Fritz Rehn. However Rehn died two months after taking office.[13] For the next two years the post of president remained vacant.[14]

Early Days of the Court

The People's Court was created outside the framework of the German constitution, although whether the Weimar-era constitution was even still in force was a matter of unresolved controversy within the Nazi Party. Regardless, in reality the führerprinzip rejected all liberal legal principles in favour of Nazi control.[15] with an editorial in the Völkischer Beobachter commenting that the People's Court was an '...expression of National Socialist basic concepts in the field of the application of the law."[16]

Despite this rejection of the rule of law, there was continuity of personnel within the judicial system, with only a few judges retiring or being removed.[15], and initially, the legal procedures of the People's Court did not differ from previous treason trials.[17] Early decisions of the court were cautious to the point that they were criticised by the Nazi regime,[12] with only four death sentences handed down in 1934 and nine in 1935.[18] Between April 1935 and August 1936, the Ministry of Justice criticized eighteen of the court’s verdicts as excessively lenient. Hitler later stated that the People’s Court, "had not initially corresponded to his desired tough standards."[19]

The Secretary of State of the Ministry of Justice, Roland Freisler, who was the driving force of the rise of the People's Court, intended to make it Germany's supreme court, superseding the Reichsgericht, with the goal of making the führerprinzip the basis of the entire judicial system. He believed that the People's Court had three advantages: speed, efficiency, and that there was no appeal against its verdicts.[20] For the Nazis, who could eliminate opponents by taking them into so-called protective custody in a concentration camp, the advantage of the People’s Court was it eliminated their enemies behind a facade of legality. This led to conflict between the Nazi appointees to the court, who understood that the court was a charade, and the conservative “judges of the old school”, who expected the law, however draconian, to be upheld in genuine trials.[21]

Thierack Presidency

Contrary to the pronouncement that the People's Court was a temporary expedient, a decree of 18 April 1936 transformed it into a “full court according to the Constitution of Courts Act”.[22] Shortly afterwards, on 1 May 1936, Otto Georg Thierack, formerly vice-president of the Reich Court of Justice, became president of the court.[23]

Expansion of jurisdiction and reduced legalism

With the accession of Thierack, the court gained prestige, symbolised by its judges being given the right to wear the red robes of the supreme court. It also increased its jurisdiction to include misprision of treason, economic sabotage, Wehrkraftzersetzung (corroding defensive strength), evading military service, sedition, and espionage.[24]

The regime had initially denied characterisation of the court as a summary or revolutionary court, claiming it was independent. However, by 1937 such pretence was dropped, with minister of justice, Franz Gürtner declaring the court to be, "a task force for combating and defeating all attacks on the external and internal security of the Reich.", the vice-president of the court stating that its members, were "politicians first and judges second", and its chief prosecutor announcing that the purpose of the court was, "to annihilate the enemies of National Socialism".[24]

The beginning of World War II brought an increased number of prosecutions (doubling from 1939 to 1940), an increase of the severity of sentencing, and an expansion of the court's jurisdiction to cover undermining morale. Suggestions such as the war being either pointless or lost, or that peace should be sought, and statements attacking Hitler in any way, were ranked as capital crimes. This was true even of private remarks, with the court declaring that "every political remark must be regarded as a public statement in principle", a position without support in law.[25]

Sources vary on how often cases of undermining morale resulted in a death sentence. Müller states that "such remarks were always punishable by death", while Koch states that "reliable statistics are difficult to compile", and Johnson shows that the law was selectively enforced, with only around a third of accusations against "ordinary Germans" in Krefeld reaching court at all, while two-thirds of accusations against non-Jews in Cologne were dismissed by the local Special Court, and only three percent were referred to the People's Court.[26]

Freisler Presidency

In August 1942, Thierack was appointed as Reich Minister of Justice and Roland Freisler was appointed as President of the People's Court.[27] Freisler had been a member of the Nazi Party since 1923.[28]

Further deterioration of legalism

Freisler took the most important cases for himself, prosecuting those accused of attacks on the Führer, as well as cases involving espionage and economic sabotage. Goebbels noted that: “Freisler... is once again the radical National Socialist he used to be. Just as he did too little as undersecretary in the Ministry of Justice, today as President of the People’s Court, he is doing too much.”[28]

Under Thierack, the People’s Court’s decisions had retained the appearance of legalism with verdicts, however predetermined, justified in lengthy written arguments.[29] However, at the time of Freisler's appointment, Goebbels gave a private speech to the court stating that the court "is not to be started from the law but from the decision that the man must be gotten rid of".[27]

Freisler’s inauguration as president of the People's Court came at a time when Germany’s military fortunes were worsening, and this was reflected in harsher sentences.[30] In 1940, 4.9% of defendants had received a death sentence, rising to 8.2% in 1941. During Freisler’s presidency, the execution rate rose dramatically. In 1942 it was 46%, and it remained at a similar level throughout his presidency.[31]

Nacht und Nebel

In 1941, the Nacht und Nebel programme — literally "night and fog" — focused on the forced disappearance of resistance activists from occupied countries, who were imprisoned without any word of their fate. Initially, it was planned to try some of these prisoners by the Reichskriegsgericht, a military court, but both the military courts and the ordinary civilian courts proved reluctant to take on cases that were expected to be drumhead trials of overt illegality. Freisler agreed that the People's Court would take on the cases,[32], and 1,200 were referred to the People’s Court, although Freisler transferred about three-quarters of them to other courts. Of the approximately two hundred cases prosecuted before the People’s Court, Freisler assigned the majority to his own First Senate. The trials themselves were a complete sham, as Justice Minister Thierack had informed Freisler that, "You will have every indictment submitted to you and will recognize... what is essential for the state.”[30]

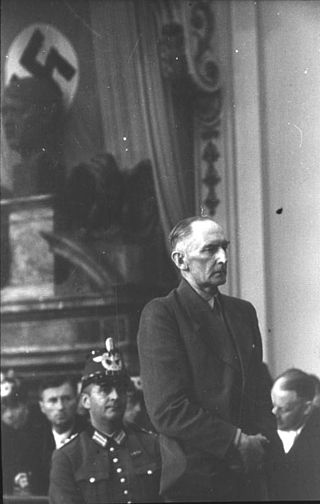

Trials of August 1944

The best-known trials in the People's Court began on 7 August 1944, in the aftermath of the 20 July plot that year. The first eight men accused were Erwin von Witzleben, Erich Hoepner, Paul von Hase, Peter Yorck von Wartenburg, Hellmuth Stieff, Robert Bernardis, Friedrich Klausing, and Albrecht von Hagen. The trials were held in the imposing Great Hall of the Berlin Chamber Court on Elßholzstrasse,[33] which was bedecked with swastikas for the occasion. There were around 300 spectators, including Ernst Kaltenbrunner and selected civil servants, party functionaries, military officers and journalists.

The accused were forced to wear shabby clothes, denied neckties and belts or suspenders for their trousers, and were marched into the courtroom handcuffed to policemen. The proceedings began with Freisler announcing he would rule on "...the most horrific charges ever brought in the history of the German people." Freisler was an admirer of Andrey Vyshinsky, the chief prosecutor of the Soviet purge trials, and copied Vyshinsky's practice of heaping loud and violent abuse on defendants.

The 62-year-old Field Marshal von Witzleben was the first to stand before Freisler, and he was immediately castigated for giving a brief Nazi salute. He faced further humiliating insults while holding onto his trouser waistband. Next, former Colonel-General Erich Hoepner, dressed in a cardigan, faced Freisler, who addressed him as "Schweinehund". When he said that he was not a Schweinehund, Freisler asked him what zoological category he thought he fitted into.

The accused were unable to consult their lawyers, who were not seated near them. None of them were allowed to address the court at length, and Freisler interrupted any attempts to do so. However, Major General Helmuth Stieff attempted to raise the issue of his motives before being shouted down, and Witzleben managed to call out "You may hand us over to the executioner, but in three months, the disgusted and harried people will bring you to book and drag you alive through the dirt in the streets!" All of the accused were found guilty and condemned to death by hanging, and the sentences were carried out shortly afterwards in Plötzensee Prison.

Another trial of plotters was held on 10 August. On that occasion the accused were Erich Fellgiebel, Alfred Kranzfelder, Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg, Georg Hansen, and Berthold Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg.

On 15 August, Wolf-Heinrich Graf von Helldorf, Egbert Hayessen, Hans Bernd von Haeften, and Adam von Trott zu Solz were condemned to death by Freisler.

On 21 August, the accused were Fritz Thiele, Friedrich Gustav Jaeger, and Ulrich Wilhelm Graf Schwerin von Schwanenfeld who was able to mention the "...many murders committed at home and abroad" as a motivation for his actions.

On 30 August, Colonel-General Carl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel, who had blinded himself in a suicide attempt, was led into the court and condemned to death along with Caesar von Hofacker, Hans Otfried von Linstow, and Eberhard Finckh.

In the aftermath of the 20 July Plot to assassinate Hitler, senior intelligence analyst Lieutenant Colonel Alexis von Roenne was arrested on account of his links with many of the conspirators. Although not directly involved in the plot, he was nonetheless tried, found guilty by the show trial, and hanged on a meat hook at Plötzensee Prison on 12 October 1944.[34]

'Traitors Before the People's Court' documentary

The trials of those involved in the 20 July Plot were filmed with the intention of making a documentary entitled Traitors Before the People's Court.[35] Hitler intended the documentary to be shown in all German cinemas in order to deter and intimidate future resistance. However, this proved impossible because of the farcical behaviour of Freisler during the trials. Instead, the film was made an official secret and only shown to a handful of party officials.[36]

The documentary turned out to be the last made for The German Weekly Review.[35]

Bombing

Field Marshal von Witzleben's prediction of Roland Freisler's fate proved slightly incorrect, as he died in a bombing raid in February 1945, approximately half a year later.[37][38]

On 3 February 1945, Freisler was conducting a Saturday session of the People's Court, when USAAF Eighth Air Force bombers attacked Berlin.[39] Government and Nazi Party buildings were hit, including the Reich Chancellery, the Gestapo headquarters, the Party Chancellery, and the People's Court. According to one report, Freisler hastily adjourned court, and had ordered that day's prisoners to be taken to a shelter, but paused to gather that day's files. Freisler was killed when an almost direct hit on the building caused him to be struck down by a beam in his own courtroom.[40] His body was reportedly found crushed beneath a fallen masonry column, clutching the files that he had tried to retrieve.[41]

Another version of Freisler's death states that he was killed by a British bomb that came through the ceiling of his courtroom as he was trying two women, who survived the explosion.[42]

A foreign correspondent reported, "Apparently nobody regretted his death."[40] Luise Jodl, the wife of General Alfred Jodl, recounted more than 25 years later that she had been working at the Lützow Hospital when Freisler's body was brought in, and that a worker commented, "It is God's verdict." According to Luise Jodl, "Not one person said a word in reply."[43]

Final days of the court

Freisler's death and the damage to the court meant no trials occurred for nearly a month.[44] Wilhelm Crohne became acting president from 4 February to 11 March 1945, before the appointment of Harry Haffner.

Among cases disrupted by the bombing was that of Fabian von Schlabrendorff, a 20 July plot member who was on trial that day and was facing execution.[45] Von Schlabrendorff was "standing near his judge when the latter met his end."[41] Freisler's death saved Schlabrendorff, as he was later re-tried and acquitted by Crohne.[46]

Arthur Nebe, former head of the Reich Criminal Police who had been implicated in the 20 July 1944 plot, was tried and sentenced to death by the People's Court in March 1945. No trials before the People's Court are documented after April 1945.[44]

On 26 April 1945, the US occupation forces were directed to abolish all extraordinary courts, including the People's Court, and arrest their judges, prosecutors, and officials for prosecution.[47] Laws implementing the directive were issued by the Allied Control Council after the Surrender of Nazi Germany.[48]

Remove ads

Composition

The People's Court was divided into senates (initially two, later rising to six). The first senate was presided over by the court's president and dealt with the most important cases.[17]

Each Senate had five judges: two judicially trained and three so-called lay judges. The lay judges supposedly represented, “the people, whose popular conception of legality they best reflect.”[49] However, they were not drawn from the public, with approximately two-thirds coming from nazi organisations and one-third from the armed forces.[14] This selection of lay judges from national socialist and military organizations was unprecedented.[49]

Judges were initially appointed for a period of five years and later for life.[20] Defense lawyers had to get permission to appear before the court and could be disqualified at any time.[50] All appointments were suggested by the Minister of Justice and confirmed by Hitler, and judges could not reject their appointment to the court.[51]

The number of trained judges expanded from 17 to 34 during the court's lifetime, while the number of lay judges expanded from 95 to 173.[52]

Remove ads

Location

The court was originally located in the former Prussian House of Lords in Berlin. Later it moved to the former Königliches Wilhelms-Gymnasium at Bellevuestrasse 15 in Potsdamer Platz (the location now occupied by The Center Potsdamer Platz, and a marker is located on the sidewalk nearby).[53]

The memorial plaque translates to the following:

Located at this spot

1935–1945

The entrance to the People's CourtIn disregard of fundamental principles of the rule-of-law-based justice system, it sentenced more than five thousand people to death, and an even greater number to prison terms. Its goal was the persecution and annihilation of opponents of the National Socialist regime.

After the bombing of the Bellevuestrasse site, the court moved to Potsdam and then its final location in Bayrouth.[51]

Process

Summarize

Perspective

Cases generally reached the People's Court via the Gestapo, who acted on the basis of information supplied by informants. The prosecuting authority, following instructions from the Ministry of Justice, would decide whether to bring an indictment to the court.[54]

Jurisdiction

The People's Court's primary jurisdiction was Germany (including annexed territories), along with the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, the General Government and, after 1941, those resisting German rule in France, Belgium, Norway and Holland.[55]

‘No crime without law’ versus ‘criminal mentality’

The Nazis believed the courts should adhere to their definition of the needs of the Volksgemeinschaft (national community), not liberal legal principle.[56] Individual rights came second to the Volksgemeinschaft's needs.[57]

Courts generally proceed from the principle that there is “no crime without law” and so they can only punish defined criminal acts. In contrast, the People’s Court proceeded from the principle that "criminal mentality", broadly defined, should be punished regardless of law, declaring that, “Whosoever... merits punishment according to the ideas fundamental to criminal law and according to the healthy common sense of the people, shall be punished. If no criminal law applies specifically to the offence, it shall be punished according to that law the fundamental idea of which best fits the offence”. [58]

In practice, the meaning of "healthy common sense of the people" became "the Führer’s will", due to the Führerprinzip. Hans Frank, President of the Academy for German Law instructed judges in 1936 that they should ask themselves when making a judgement, "How would the Führer decide in my place?", and Reich Justice Curt Rothenberger stated, "The judge is on principle bound by the law. The laws are the orders of the Führer".[59]

A variety of novel legal arguments enabled the People’s Court to prosecute people for their supposed criminal mentality. In particular, the court extended the definition of "preparation for high treason" to:

- Include other crimes.

- Allow the death penalty for crimes that didn’t warrant the death penalty in law.

- Relax the rules of evidence used by the court.

- Argue that any crime committed by a Communist was preparation for treason.

- Allow prosecution of "crimes" that were undefined in law.[60]

This expansion of the definition of treason made the death penalty applicable to even the slightest resistance, with the court stating that, “even the most remote preparation—even a preparation for a preparation—is punishable”.[61] It also enabled laws to be applied ex post facto to actions that were not criminalized at the time and to actions "that would be regarded as trifling in any non-despotic society", such as anti-Nazi jokes.[32]

The result was that the definition of a crime was in the hands of the People’s Court judges, who had discretion to impose the death sentence regardless of law.[62]

Legal conventions rejected

The People's Court was distinguished from previous German courts by its open understanding that The rule of law and civil and political rights were subordinate to supporting Nazi supremacy. As Thierack wrote to Freisler when he became president of the court, "the judge of the People's Court must become accustomed to seeing primarily the ideas and intentions of the leadership of the state, while the human fate that depends on it is only secondary".[63]

To achieve this aim, the court rejected liberal legal conventions such as judicial independence, due process, the right to appeal, and the right to counsel:

- All the judges on the People’s Court were either members of the Nazi Party or conservative ideological sympathizers.[64] Its judgments were not impartial, and its judges were subservient to the wishes of the Nazi regime.[56]

- Although the court had claimed the right to ignore double jeopardy as early as 1938, it was fully abolished after the outbreak of the war. Retrials almost always increased the severity of punishment, and seven out of ten retrials resulted in the death penalty.[65]

- Defense lawyers were constrained by the threat of arrest or disciplinary action, insufficient preparation time, and inadequate contact with the defendant. They were also restricted in requesting retrials and were strongly discouraged from appealing for a pardon.[66]

- In at least one case (the trial of the White Rose conspirators), the defense lawyer assigned to Sophie Scholl chastised her the day before the trial, stating that she would pay for her crimes.[67]

- The People's Court's verdicts were not appealable.[68]

- Children were tried as adults rather than having the protection of juvenile law.[69]

Remove ads

Victims

Summarize

Perspective

Statistics regarding the People's Court are only available until mid 1944, so exact figures on the number of cases and victims are not available.[70] However, various estimates have been made:

- Wachsmann and Hoffmann give figures of 10,980 people sentenced to prison and 5,179 executed.[71][72]

- Räbiger states that in 7,000 cases 18,000 defendants were convicted, 5,000 were sentenced to death and about 1,000 were acquitted.[73]

- Müller states that there were at least 14,319 defendants, of which at least 5,191 were executed and 1073 acquitted.[70]

- Rachlin states that a figure of between five and six thousand executions is credible. [74]

Acquittals

The People's Court acquitted more defendants than its reputation suggests.[55] The acquittal rate in 1940 was 7.3%. It then fell to around 5% until 1944, when it rose to almost 12%.[75]

Cases that were dismissed or acquitted were usually because the accused appeared to have mental health issues and/or they were allegedly part of an accused group but there was little evidence connecting them to the group. However, although these individuals were acquitted or had their cases dismissed, the SS often took them into so-called protective custody in a concentration camp after the court discharged them.[76]

Pre-war sentencing

During the pre-war years, the People’s Court retained a semblance of legal procedure, and its sentencing was neither indiscriminate nor a complete sham.[77] People’s Court judges retained a degree of discretion in imposing sentences as the Nazi regime wanted judicial outcomes to reflect what they believed to be the popular will, and that required granting flexibility to its judges to move beyond legal precedent.[78]

During the period, the People's Court, on average, sentenced two percent of defendants to death. However, it treated members of the KPD and SPD more harshly. Twelve percent of KPD leaders brought before the court received death sentences or long terms of hard labour, and three-quarters of the defendants sentenced to death belonged to the KPD. In contrast, people involved with smaller parties, Catholic, or right-wing organizations generally received lighter punishment.[79]

Wartime sentencing

As the war progressed, the Nazi regime became more brutal, insisting the legal system deliver ever-more ruthless summary justice.[80] Cases of every kind increased enormously. Between 1939 and 1940, the number of death sentences handed down by the People's and Special Courts increased tenfold, from 99 to 929, and between 1941 and 1943 they quadrupled again, from 1,292 to 5,336.[81]

Following the Battle of Stalingrad in early 1943, the People’s Court increasingly prosecuted defeatism, leading to a further degeneration of procedure. Oswald Rothaug was made responsible for defeatism cases, which involved prosecuting people for even the most trivial remarks. In 1943, the People’s Court handled about 2,500 cases of defeatism.[27] Even clearly being innocent of the charges could not be relied on as a defence. In 1944, Leopold Felsen was brought before the court after being accused of listening to foreign broadcasts by his wife. He pointed out to the court that she had been trying to get rid of him since 1939, and his daughter admitted in court that she had been threatened into lying by her mother. The People’s Court nevertheless condemned Felsen to death.[82]

Executions

More than 1,500 of those found guilty by the People's Court were executed in Plötzensee Prison in Berlin.[83]

Selected Victims

- 1941 – Heinz Kapelle. A leader of the Young Communist League of Germany. Sentenced to death on 20/21 February, executed on 1 July, at the age of 27.

- 1942 – Helmuth Hübener. Beheaded at the age of 17, he was the youngest opponent of Nazi Germany executed as a result of a trial by the People's Court.

- 1942 – Maria Restituta Kafka. A Catholic nun and surgical nurse who was found guilty of distributing regime-critical pamphlets and beheaded.

- 1943 – Otto and Elise Hampel. The couple carried out civil disobedience in Berlin, were caught, tried, sentenced to death by Freisler, and executed. Their story formed the basis for the 1947 Hans Fallada novel Every Man Dies Alone/Alone in Berlin.

- 1943 – Members of the White Rose resistance movement: Sophie Scholl, Hans Scholl, Alexander Schmorell, Willi Graf, Christoph Probst and Kurt Huber.

- 1943 – Julius Fučík. A Czechoslovak journalist, Communist Party of Czechoslovakia leader, and a leader in the forefront of the anti-Nazi resistance. On 25 August 1943, in Berlin, he was accused of high treason in connection with his political activities. He was found guilty and hanged two weeks later on 8 September 1943.

- 1943 – Karlrobert Kreiten, a pianist. Nazi Party member Ellen Ott-Monecke notified the Gestapo of Kreiten's negative remarks about Adolf Hitler and the war effort. Kreiten was indicted at the Volksgerichtshof, with Freisler presiding, and condemned to death. Friends and family frantically tried to save his life, to no avail. The family was never notified officially about the judgment, and only accidentally learned that Kreiten had been executed with 185 other inmates in Plötzensee Prison.

- 1943 – Max Sievers, communist and former chairman of the German Freethinkers League. He fled to Belgium after the Nazis came to power, but they caught up with him after invading that country. He was convicted of "conspiracy to commit high treason along with favouring the enemy", sentenced to death, and beheaded by guillotine on 17 February 1944.

- 1943 – The Lübeck martyrs. Johannes Prassek, Eduard Müller, Hermann Lange and Karl Friedrich Stellbrink

- 1943 – Elfriede Scholz. A tailor living in Dresden, she was the younger sister of Erich Maria Remarque, author of All Quiet on the Western Front, who had fled into exile before the war. She was arrested in August 1943 for Wehrkraftzersetzung (undermining defensive capability) for saying to a customer that the war was lost. Freisler declared, "Ihr Bruder ist uns leider entwischt—Sie aber werden uns nicht entwischen" ("Your brother is unfortunately beyond our reach — you, however, will not escape us").

- 1944 – Max Josef Metzger, a German Catholic priest. Metzger was the founder of the brotherhood Una Sancta, a group devoted to the reunification of Roman Catholics and Lutherans. During the trial, Freisler stated to Metzger, that "such a plague had to be eradicated".

- 1944 – Erwin von Witzleben. A German Field Marshal, Witzleben was a military conspirator in the 20 July Bomb Plot to kill Hitler. Witzleben, who would have been Commander-in-Chief of the Wehrmacht in the planned post-coup government, arrived at Army Headquarters (OKH-HQ) in Berlin on 20 July to assume command of the coup forces. He was arrested the next day and tried by the People's Court on 8 August. Witzleben was sentenced to death and hanged the same day in Plötzensee Prison.

- 1944 – Johanna "Hanna" Kirchner. A member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany.

- 1944 – Lieutenant Colonel Caesar von Hofacker. A member of a resistance group in Nazi Germany. Hofacker's goal was to overthrow Hitler.

- 1944 – Carl Friedrich Goerdeler. Conservative German politician, economist, civil servant and opponent of the Nazi regime, who would have served as the Chancellor of the new government had the 20 July plot of 1944 succeeded.

- 1944 – Otto Kiep – the Chief of the Reich Press Office (Reichspresseamts), who became involved in resistance.

- 1944 – Elisabeth von Thadden, as well as other members of the anti-Nazi Solf Circle.

- 1944 – Heinrich Maier, an Austrian priest who very successfully passed on plans and production sites for V-2 rockets, Tiger tanks, and planes to the Allies. In contrast to many other German resistance groups, the Maier group informed very early about the mass murder of Jews. The head of a Vienna resistance group was killed on the last day of execution in Vienna after several months of torture in the Mauthausen concentration camp.

- 1944 – Julius Leber – German politician of the SPD and a member of the German Resistance against the Nazi regime.

- 1944 – Johannes Popitz – Prussian finance minister and a member of the German Resistance against Nazi Germany.

- 1945 – Helmuth James Graf von Moltke. German jurist, a member of the opposition against Adolf Hitler in Nazi Germany, and a founding member of the Kreisau Circle dissident group.

- 1945 – Klaus Bonhoeffer and Rüdiger Schleicher – German resistance fighters.

- 1945 – Erwin Planck. Politician, businessman, resistance fighter and son of physicist Max Planck. Planck was an alleged conspirator in the 20 July plot.

- 1945 – Arthur Nebe. An SS-Lieutenant General (Gruppenführer). Nebe was a conspirator in the 20 July Plot to kill Hitler. He was the head of the Kriminalpolizei, or Kripo, and the commander of Einsatzgruppe B. Nebe oversaw massacres on the Russian Front, and at other locations as he was commanded to do by his superiors in the SS. After the failure to assassinate Hitler, Nebe hid on an island in the Wannsee until he was betrayed by one of his mistresses. On 21 March 1945 Nebe was hanged, allegedly with piano wire (Hitler wanted members of the plot "hanged like cattle"[84]) at Plötzensee Prison.

Remove ads

Aftermath

Summarize

Perspective

Legal aftermath

Nuremberg Trials

Former president of the People's Court Otto Georg Thierack was taken prisoner by the British after the end of World War II. It was intended that he would be brought to trial before the court at the Judges' Trial of 1947, one of the subsequent Nuremberg proceedings, but he committed suicide before the trial began.[85]

The People's Court Chief Public Prosecutor Ernst Lautz, was sentenced to ten years imprisonment during the Judges' Trial. During his trial, Lautz, who had never been a member of the Nazi party, did not accept that his actions had undermined the rule of law, blaming Freisler for its excesses.[21] Lautz was released after serving less than four years of his sentence and was granted a government pension by West Germany.

Oswald Rothaug, formerly a judge of the People's Court was sentenced to life imprisonment on 14 December 1947 for crimes against humanity. His sentence was later reduced to twenty years, and he was released on parole on 22 December 1956.[86]

West Germany

No judges associated with the People’s Court were successfully prosecuted by the West German justice system. Hans-Joachim Rehse, a former People's Court judge, was tried in Berlin in July 1967. Initially found guily and sentenced to five years' imprisonment, he was acquitted on appeal.[87] This was due to the 1946 invention of a Richterprivileg (judicial privilege) which declared that a judge could only be prosecuted for their verdicts if they had intentionally perverted the course of justice. Rehse argued that he had believed his actions to be legal under laws in effect at the time, so there was no intentionality.[88] The acquittal caused a scandal.[89]

After Rehse was acquitted, all other cases against People's Court judges and prosecutors were dropped for over a decade until, in 1979, investigations restarted. In 1982, Die Weiße Rose, a movie dramatizing the trial of the White Rose resistance group before the People's Court, included a closing statement that "It is the opinion of the Federal Court that the sentences of the White Rose were legal. They are still in force." Whilst not accepting the accuracy of the statement, the President of the Federal Court distanced himself from the Rehse decision and suggested the Bundestag should consider annulling the sentences of the People's Court.[90]

Following this, in 1984, a further attempt to prosecute a People's Court judge, Paul Reimers, was made which rejected the concept of judicial privilege.[91] The Reimers trial was abandoned when he committed suicide, and by 1986 all other investigations into People's Court judges and prosecutors had been abandoned.[92]

At least 29 People's Court judges and 69 prosecutors had careers in the West German court system.[93] However, negative publicity surrounding the Rehse trial led to the early retirement of many, including Reimers, with all the retirees receiving state pensions.[91]

East Germany

Heino von Heimburg, a People's Court lay judge, died in 1945 in a prisoner-of-war camp in the Soviet Union.

In the Soviet occupation zone on June 29, 1948, four former People's Court judges and prosecutors were sentenced to prison terms. In East Germany five members of the People's Court were convicted, including one, Wilhelm Klitzke, who received a death sentence.[94]

Other People's Court judges joined the East German judiciary.[95] In addition, Arno von Lenski, who had been a lay judge in the People's Court and had signed several death sentences, became a general in the National People's Army and later a deputy in the Volkskammer.[96]

Nullification of People's Court verdicts

All judgments of the People’s Court were reversed by German Federal Law on 28 May 1998.[97]

Declaration of the Bundestag

On January 25, 1985, the West German Bundestag passed a legally non-binding resolution declaring the People's Court to be an instrument of judicial murder and state terrorism, stating: "The Volksgerichtshof was an instrument of state-sanctioned terror, which served one single purpose, which was the destruction of political opponents. Behind a juridical facade, state-sanctioned murder was committed." It also stated that the judgments of the court had no legal effect in the Federal Republic of Germany.[98]

Characterization of the People’s Court

The People's Court is associated with summary justice, execution, and denial of civil and legal rights.[64] Because of its rejection of legal convention, it has been characterized as “symbolic of the wanton criminality and corruption of the Third Reich”, as a “court in name only,” a “terror court,” a “blood tribunal,” “an instrument of terror in the enforcement of National Socialist tyranny,” [56], as "essentially a revolutionary tribunal... to persecute and intimidate political opponents of the regime",[99] and as the "death machine of the Nazi Party".[100]

Remove ads

See also

- Judicial murder

- List of members of the 20 July plot

- Presumption of guilt

- Tribunale speciale per la difesa dello Stato (1926–1943) (a court with comparable tasks which existed in Fascist Italy)

- Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the Soviet Union (a Soviet court which was responsible for many show trials)

- Revolutionary Tribunal ( similar court which existed during the Reign of Terror during the French Revolution)

Remove ads

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads