Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Swan Lake

1877 ballet by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Swan Lake (Russian: Лебеди́ное о́зеро, romanized: Lebedínoje ózero, Russian pronunciation: [lʲɪbʲɪˈdʲinəjə ˈozʲɪrə]), Opus 20, is a ballet composed by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky between August 1875 and April 1876.[1] The original production premiered at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow on 4 March 1877 (20 February Old Style), with choreography by Julius Reisinger. The ballet, initially conceived in two acts, is based on Russian and German folk tales and tells the story of Princess Odette, who is transformed into a swan by the sorcerer Von Rothbart.[2][3][4]

This article incorporates text from a large language model. (October 2025) |

The initial reception was lukewarm, with criticism directed at various elements of the production. Despite this, Swan Lake has become one of the most frequently performed ballets worldwide.[5]

Most modern productions derive their choreography and music from the 1895 revival, which was staged by the Imperial Ballet at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg on 15 January 1895. This revival was choreographed by Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov. The musical score was revised by Riccardo Drigo, the chief conductor of the St. Petersburg Imperial Theatre. The 1895 version extended the ballet to four acts and restructured the storyline, establishing a framework that has shaped subsequent stagings.[6]

The ballet’s narrative centers on the relationship between Prince Siegfried and Odette, the Swan Queen, and includes well-known sequences such as the Dance of the Little Swans and the Black Swan pas de deux. Swan Lake’s themes of transformation, love, and redemption are set against Tchaikovsky’s symphonic score, noted for its complexity and emotional depth.[7]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

Uncertain Libretto Origins

The original libretto’s authorship and exact origin are unclear. It may draw from Russian and German folk tales, including Johann Karl August Musäus’s 1784 story The Stolen Veil, linked to the Swan Maiden legend, though similarities to the ballet’s plot are limited.

The story likely developed through ballet traditions rather than one author. Critics find elements from legends worldwide and common German settings in 19th-century ballets. Siegfried resembles Albrecht from Giselle, both betrayed by deception. The ball to choose a bride appears in La fille du Danube. Swan maidens echo wilis and sylphs from Romantic ballets and connect to Daniel Auber’s opera Le lac des fées.[8][9][10][11][12][13][14]

Authorship Theories

- Julius Reisinger, the original choreographer and a Bohemian likely familiar with The Stolen Veil, might have created the story.

- Vladimir Begichev, Director of Moscow’s Imperial Theatres, possibly with danseur Vasily Geltser, a libretto copy names Begichev.

- A journalist may have written the first libretto based on early rehearsals explaining differences from Tchaikovsky’s score.

- Tchaikovsky possibly invented the story himself, adapting from his earlier ballet The Lake of the Swans.

Tchaikovsky's influences

From the late 1700s to the 1890s, ballet music was usually written by specialists who created light, and rhythmically clear works. Before starting Swan Lake, Tchaikovsky studied the style of composers such as Cesare Pugni and Ludwig Minkus. He especially took inspiration from Léo Delibes, Adolphe Adam, and Riccardo Drigo, mentioning them in letters to his protégé Sergei Taneyev. When writing Swan Lake, Tchaikovsky reused themes from earlier works. His nephew and niece said he had written a small ballet called The Lake of the Swans in 1871, which already contained the “Swan’s Theme.” He also borrowed music from his abandoned opera The Voyevoda and from his unfinished opera Undina. By April 1876, the score was finished and rehearsals began. Choreographer Julius Reisinger rejected some parts as hard to dance to and used other composers’ music instead. Tchaikovsky objected, and his music was restored.[15][16]

Composition process

Tchaikovsky’s enthusiasm for Swan Lake is reflected in the speed of its composition. Commissioned in the spring of 1875, the score was completed within a year. In letters to Sergei Taneyev dated August 1875, he explained that his haste was driven not only by excitement for the project but also by a desire to complete it quickly, thereby freeing himself to begin work on an opera. He first composed the scores for the opening three numbers, before undertaking the orchestration in the autumn and winter, and continued to wrestle with the instrumentation well into the spring. By April 1876 the work was finished. His reference to an early draft implies the existence of a preliminary outline, though no such document has ever been found. In correspondence with friends he spoke of his long‑standing wish to write for the ballet stage, describing this particular commission as both stimulating and laborious in equal measure.[17]

Performance history

Moscow première (world première)

- Date: 4 March (OS 20 February) 1877

- Place: Bolshoi Theatre, Moscow

- Balletmaster: Julius Reisinger

- Conductor: Stepan Ryabov

- Scene Designers: Karl Valts (acts 2 & 4), Ivan Shangin (act 1), Karl Groppius (act 3)

St. Petersburg première

- Date: 27 January 1895

- Place: Mariinsky Theatre, St. Petersburg

- Balletmaster: Marius Petipa (acts 1 & 3), Lev Ivanov (acts 2 & 4)

- Conductor: Riccardo Drigo

- Scene Designers: Ivan Andreyev, Mikhail Bocharov, Henrich Levogt

- Costume Designer: Yevgeni Ponomaryov[18]

Other notable productions

- 1880 and 1882, Moscow, Bolshoi Theatre, staged by Joseph Hansen after Reisinger, conductor and designers as in première

- 1901, Moscow, Bolshoi Theatre, staged by Aleksandr Gorsky, conducted by Andrey Arends, scenes by Aleksandr Golovin (act 1), Konstantin Korovin (acts 2 & 4), N. Klodt (act 3)

- 1911, London, Ballets Russes, Sergei Diaghilev production, choreography by Michel Fokine after Petipa–Ivanov, scenes by Golovin and Korovin

- 1934, London, Royal Opera House company premiere, The Vic-Wells Ballet

- 1946, London, Royal Opera House premiere, Sadler's Wells Ballet

Original interpreters

Original 1877 Production

Swan Lake premiered on March 4, 1877, at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow as a benefit performance for ballerina Pelageya (Polina) Karpakova, who danced Odette, while Victor Gillert performed as Prince Siegfried. Karpakova might have also danced Odile, though the original plan called for separate performers in those roles, while today, one ballerina typically plays both. The role of Odette was first meant for Russian ballerina Anna Sobeshchanskaya, but a Moscow official's objections led to her replacement. Tchaikovsky, the composer's brother, blamed the poor sets and costumes, lack of star performers, weak choreography, and subpar orchestra. Despite the failure, the production ran for six years with 41 performances, outlasting several other ballets in the theatre’s repertory.[20][21][22][23][24][25][26]

Tchaikovsky Pas de Deux (1877)

In Julius Reisinger’s 1877 Moscow premiere of Swan Lake, ballerina Anna Sobeshchanskaya first danced the dual role of Odette and Odile. After her debut on 26 April 1877, she asked Marius Petipa to create a new piece for Act III, at the time, prominent dancers often requested custom dances, which were considered their property.[27]

Petipa choreographed a pas de deux to music by Ludwig Minkus, the Imperial Theatres’ composer. Following the traditional form, it included an entrée, adage, separate variations, and a coda. Tchaikovsky subsequently insisted that he alone should control the ballet’s music, however, he agreed to write a new pas de deux for Sobeshchanskaya. Because she wanted to keep Petipa’s choreography, Tchaikovsky carefully matched the music to her steps so she wouldn’t need to rehearse again. Content, she asked for and received an extra variation. For many years the piece was thought lost, until 1953, when a repetiteur score was found in the Moscow Bolshoi Theatre archives. It was filed among materials for Alexander Gorsky’s 1912 revival of Le Corsaire, where he had reused the piece. [28][29][30]

In 1960, George Balanchine revived the music by creating a new pas de deux for Violette Verdy and Conrad Ludlow. Premiered in New York at the City Center of Music and Drama, it was titled Tschaikovsky Pas de Deux and remains performed worldwide today.[31]

Subsequent productions 1879–1894

Julius Reisinger was succeeded as ballet-master by Joseph Peter Hansen, who made notable attempts to revive Swan Lake. On 13 January 1880 he presented a new production for his own benefit performance, with Evdokia Kalmykova, a pupil of the Moscow Imperial Ballet School, in the dual role of Odette/Odile, partnered by Alfred Bekefi as Prince Siegfried. This staging was received more favourably than the original, though it fell short of genuine success.

On 28 October 1882 Hansen mounted yet another version of Swan Lake, again casting Kalmykova as Odette/Odile. For this production he interpolated a Grand Pas into the ballroom scene, entitled La Cosmopolitana, adapted from the European section of the Grand Pas d’action "The Allegory of the Continents" in Marius Petipa’s 1875 ballet The Bandits, set to music by Ludwig Minkus. Hansen’s version of Swan Lake was performed only four times, the last of which took place on 2 January 1883, after which the ballet disappeared from the repertory.

In all, Swan Lake was performed 41 times between its première and the final performance of 1883, a rather lengthy run for a ballet that was so poorly received upon its première. Hansen became Balletmaster to the Alhambra Theatre in London and on 1 December 1884 he presented a one-act ballet titled The Swans, which was inspired by the second scene of Swan Lake. The music was composed by the Alhambra Theatre's chef d'orchestre Georges Jacoby.

On 21 February the second scene of Swan Lake was presented in Prague by the Ballet of the National Theatre, in a staging by Balletmaster August Berger. The work was performed as part of two concerts conducted by Tchaikovsky himself, who recorded in his diary that he had experienced "a moment of absolute happiness" on hearing the ballet performed. Berger’s production adhered to the 1877 libretto, though the names of Prince Siegfried and Benno were changed to Jaroslav and Zdeňek, with the role of Benno danced by a woman en travestie. Berger himself performed as Prince Siegfried, partnered by Giulietta Paltriniera-Bergrova as Odette. The production received only eight performances, and although plans were made for its transfer to the Fantasia Garden in Moscow in 1893, these were never realised.

Petipa–Ivanov–Drigo revival of 1895

In the late 1880s and early 1890s Marius Petipa and Ivan Vsevolozhsky entered into discussions with Tchaikovsky concerning a possible revival of Swan Lake. However, Tchaikovsky died on 6 November 1893, just as these plans were beginning to take shape. It remains uncertain whether he himself intended to revise the score for the new production. Following his death, Riccardo Drigo prepared a revised version of the music, with the approval of Tchaikovsky’s younger brother, Modest Ilyich Tchaikovsky. There are substantial differences between Drigo’s adaptation and the original 1877 score, and it is Drigo’s revision, not Tchaikovsky’s first version, that forms the basis of most productions today.

In February 1894 two memorial concerts organised by Ivan Vsevolozhsky were held in honour of Tchaikovsky. The programme included the second act of Swan Lake, staged by Lev Ivanov, Second Ballet-master of the Imperial Ballet. Attendance proved lower than expected, owing partly to the mixed character of the programme and the unusually high ticket prices, and the theatre was left half empty. Nevertheless, Ivanov’s choreography for Swan Lake was met with unanimous critical acclaim, and the performance itself was warmly received by those in attendance.[32]

The revival of Swan Lake was conceived as the benefit performance for Pierina Legnani during the 1894–1895 season. The death of Tsar Alexander III on 1 November 1894, however, led to a period of official mourning during which all rehearsals and ballet performances were suspended. This hiatus allowed full attention to be devoted to preparations for the major revival of Swan Lake. The production was a collaboration between Lev Ivanov and Marius Petipa: Ivanov retained his choreography for the second act and created the fourth, while Petipa was responsible for staging the first and third acts.

Modest Tchaikovsky was entrusted with revising the ballet’s libretto. His alterations included transforming Odette from a supernatural swan-maiden into a mortal woman placed under a curse, recasting the antagonist from Odette’s stepmother to the sorcerer von Rothbart, and reshaping the conclusion. In the revised ending, Odette chooses to drown herself, with Prince Siegfried electing to share her fate rather than live without her; their spirits are then reunited in an apotheosis.[33] In addition to these narrative changes, the structure of the ballet was altered from four acts to three, with the original second act becoming the second scene of the first act.

By early 1895 preparations were complete, and the ballet received its première on 27 January. Pierina Legnani appeared in the dual role of Odette/Odile, partnered by Pavel Gerdt as Prince Siegfried, with Alexei Bulgakov as Rothbart and Alexander Oblakov as Benno. The production was favourably received, with most reviews in the St Petersburg press expressing approval.

In contrast to the triumphant reception of The Sleeping Beauty, Swan Lake did not immediately secure a dominant place in the repertory of the Mariinsky Theatre. Between its première and the 1895–1896 season it was given only sixteen performances, and it was omitted entirely in 1897. Even more striking, the ballet was staged just four times across 1898 and 1899. For several years the work was associated exclusively with Pierina Legnani, who retained it as her preserve until her return to Italy in 1901. Thereafter the rôle passed to Mathilde Kschessinskaya, whose interpretations were regarded as equally distinguished as those of her Italian predecessor.

Later productions

Throughout its performance history, it is the 1895 version of Swan Lake that has provided the foundation for almost all subsequent stagings. While nearly every balletmaster or choreographer who has revived the work has introduced alterations to the scenario, the traditional choreography for the dances has generally been preserved and is regarded as virtually inviolable. Over time, the rôle of Prince Siegfried has also assumed greater prominence, a development closely linked to the evolution of male ballet technique.

In 1922 the Finnish National Ballet became the first European company outside the Russian sphere to mount a full production of Swan Lake. Until its Helsinki première that year, the ballet had been performed only by Russian and Czech companies, with Western Europe having encountered the work solely through visiting Russian troupes.[34]

In 1940 the San Francisco Ballet became the first American company to present a complete production of Swan Lake. The staging featured Lew Christensen as Prince Siegfried, Jacqueline Martin as Odette, and Janet Reed as Odile. Willam Christensen drew upon the Petipa–Ivanov version for his choreography, and enlisted the expertise of San Francisco’s community of Russian émigrés, among them Princess and Prince Vasili Alexandrovich of Russia, to ensure that the production reflected the traditions of Russian ballet and served as a vehicle for preserving Russian culture in the city.[35]

Several significant productions of Swan Lake have departed from both the 1877 original and the 1895 revival.

- In 1967 Erik Bruhn produced and danced in a new staging of Swan Lake for the National Ballet of Canada, distinguished by Desmond Healey’s striking designs in a predominantly black-and-white palette. While substantial portions of the traditional Petipa–Ivanov choreography were preserved, Bruhn introduced notable musical as well as choreographic alterations. Most controversially, he reconceived the character of Von Rothbart as the malevolent Black Queen, thereby adding a psychological dimension to the Prince’s troubled relationships with women, including his domineering mother.[36][37]

- Illusions Like "Swan Lake" (1976), choreographed by John Neumeier for the Hamburg Ballet, reimagined the classical work by intertwining it with the life of Ludwig II of Bavaria, whose well‑documented fascination with swans provided the link. Neumeier retained much of Tchaikovsky’s original score, supplementing it with additional music by the composer, while blending elements of the traditional Petipa–Ivanov choreography with his own new dances and dramatic scenes. The ballet concludes with Ludwig’s drowning while incarcerated in an asylum, set against the dramatic finale of Act III. With its focus on an unhappy monarch compelled into a marriage for dynastic reasons. The work inspired later reinterpretations of Swan Lake by choreographers such as Matthew Bourne and Graeme Murphy. Illusions Like "Swan Lake" remains part of the repertory of leading German ballet companies.[38][39][40][41]

- Matthew Bourne’s re‑imagining of Swan Lake diverged radically from tradition by replacing the female corps de ballet with male swans and reframing the narrative around the psychological burden of modern royalty, focusing on a prince torn between his sexuality and his distant mother. Since its première, the production has toured extensively to Greece, Israel, Turkey, Australia, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Russia, France, Germany, the Netherlands, the United States, Ireland, and the United Kingdom, and has received more than thirty international awards.[42][43][44][45]

- The 2000 production of Swan Lake by the American Ballet Theatre (recorded for television in 2005) diverges from the traditional staging in which the curtain remains lowered during the slow introduction. Instead, this music accompanies a newly created prologue that depicts Rothbart’s initial transformation of Odette into a swan. This addition recalls Vladimir Burmeister’s 1953 staging at the Stanislavsky Theatre in Moscow, though with notable differences. In this version, Rothbart is portrayed by two performers: one as a handsome young man who beguiles Odette during the prologue, and the other, in grotesque "monster" make-up, representing the sorcerer’s true form. A parallel image appears in the opening sequence of the film Black Swan, in which Natalie Portman, as Nina, dreams the transformation.[22][46][47][48][49][50]

- Graeme Murphy’s Swan Lake, first performed in 2002, was loosely inspired by the collapse of the marriage between Lady Diana and Prince Charles, and by his relationship with Camilla Parker Bowles. In this reinterpretation, the traditionally separate roles of Rothbart and Odile are unified in the character of a Baroness, shifting the narrative emphasis towards a love triangle.[51]

- In 2010, the psychological thriller Black Swan, directed by Darren Aronofsky and starring Natalie Portman and Mila Kunis, prominently integrated thematic and musical elements from Swan Lake. The narrative was conceived as a contemporary reimagining of Tchaikovsky’s ballet, employing its motifs not only in the film’s score, adapted and re-orchestrated by composer Clint Mansell, but also as a structural and symbolic framework. The story follows a ballerina cast in the dual role of Odette, the White Swan, and Odile, the Black Swan, thereby mirroring the ballet’s central themes of duality, transformation, and the conflict between purity and sensuality. Portman’s performance as Nina Sayers, a dancer whose pursuit of perfection spirals into psychological disintegration, drew explicit parallels with the tragic fate of the Swan Queen in Tchaikovsky’s work. Aronofsky has remarked that Swan Lake’s narrative of innocence corrupted and self-destruction served as a direct inspiration for the film’s dramatic trajectory. The choreography, overseen by New York City Ballet dancer and choreographer Benjamin Millepied, incorporated sequences from classical productions of Swan Lake while adapting them to suit the film’s darker, expressionistic vision.The film garnered widespread critical acclaim, particularly for Portman’s performance, which earned her the Academy Award for Best Actress. Black Swan has since been analysed for its intertextual appropriation of Swan Lake, with scholars in film and performance studies noting its transformation of a canonical ballet into a psychological allegory on ambition, repression, and artistic sacrifice.[52][53][54][55][56]

- In 2010, South African choreographer and ballet dancer Dada Masilo, remade Tchaikovsky's classic.[57] Her interpretation combined elements of classical ballet with influences from African dance. She further introduced a narrative innovation by reimagining Odile, the Black Swan, not as a female character but as a male swan, portrayed with a homoerotic dimension.[58][59]

- A Swan Lake, choreographed by Alexander Ekman and composed by Mikael Karlsson, was created for the Norwegian National Ballet. The first act combines elements of dance and spoken theatre, reflecting on the original production of Swan Lake and incorporating performances by two stage actors and a soprano. In the second act, the stage is transformed by the introduction of 5,000 litres of water, providing the setting for the dramatic confrontation between the White Swan and the Black Swan.[60][61][62][63]

Remove ads

Instrumentation

Swan Lake is scored for the typical late 19th-century large orchestra:

- Strings: violins I and II; violas, violoncellos; double basses, harp

- Woodwinds: piccolo; 2 flutes; 2 oboes; 2 clarinets in B♭, A and C; 2 bassoons

- Brass: 4 French horns in F; 2 cornets in A and B♭; 2 trumpets in F, D, and E; 3 trombones (2 tenor, 1 bass); tuba

- Percussion: timpani; snare drum; cymbals; bass drum; triangle; tambourine; castanets; tam-tam; glockenspiel; chimes

Remove ads

Roles

- Princess Odette (the Swan Queen, the White Swan, the Swan Princess), a beautiful princess, who has been transformed into a white swan

- Prince Siegfried, a handsome Prince who falls in love with Odette

- Baron Von Rothbart, an evil sorcerer, who has enchanted Odette

- Odile (the Black Swan), Rothbart's daughter

- The Queen, Prince Siegfried's mother

- The princesses who are the prince's brides.

Synopsis

Summarize

Perspective

Swan Lake is most commonly staged either in four acts across four scenes, a format prevalent outside Russia and Eastern Europe, or in three acts comprising four scenes, more typical within those regions. The most significant variation among productions worldwide concerns the conclusion: while the original ending was tragic, many modern interpretations have been adapted to provide a more optimistic resolution.

Prologue

In certain productions, a prologue is introduced depicting Odette’s initial encounter with Rothbart and her subsequent transformation into a swan.

Act 1

A magnificent park before a palace

[Scène: Allegro giusto], Prince Siegfried celebrates his birthday in the company of his tutor, friends, and local peasants [Waltz]. The festivities are interrupted by the arrival of his mother, the Queen [Scène: Allegro moderato], who expresses concern about his carefree existence. She reminds him that at the royal ball to be held the following evening, he must select a bride (in some productions, potential candidates are already introduced in this scene). Distressed by the prospect of being denied the freedom to marry for love, Siegfried becomes sombre. His companion, Benno, together with the tutor, attempts to lift his spirits. As dusk descends [Sujet], Benno observes a flight of swans passing overhead and suggests a hunt [Finale I]. Siegfried and his friends seize their crossbows and set off in pursuit.

Act 2

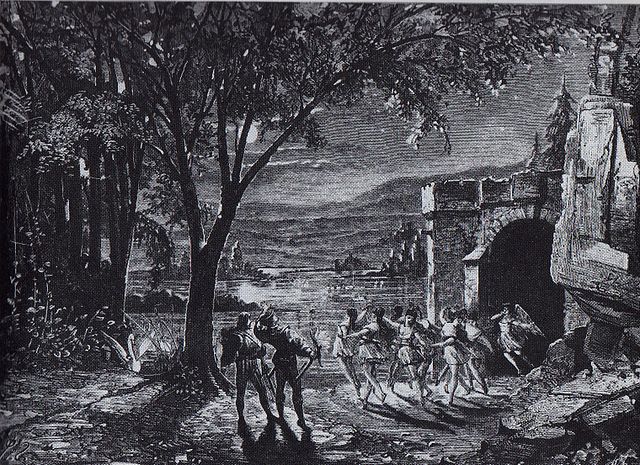

A lakeside clearing in a forest by the ruins of a chapel. A moonlit night.

Siegfried becomes separated from his companions and arrives at a lakeside glade just as a flock of swans alights [Scène. Moderato]. He raises his crossbow [Scène. Allegro moderato], yet hesitates upon witnessing one of the swans transform into a maiden of remarkable beauty, Odette [Scène. Moderato]. Initially, she recoils in fear, however, following his assurance that he intends her no harm. She and her fellow swans are subject to an enchantment imposed by the sinister and owl-like sorcerer Rothbart. By day, they assume the form of swans, and only at night, beside the enchanted lake, born of the tears of Odette's mother, do they regain their human guise. The enchantment may be lifted solely if one who has never before loved pledges eternal devotion to Odette. Rothbart appears abruptly [Scène. Allegro vivo]. Siegfried prepares to strike, but Odette intervenes, cautioning that the spell shall remain unbroken should Rothbart perish before the conditions for its dissolution are fulfilled.

As Rothbart vanishes, the swan maidens begin to populate the glade [Scène: Allegro, Moderato assai quasi andante]. Siegfried then deliberately destroys his crossbow and endeavours to earn Odette's trust, leading to the blossoming of their mutual affection. Yet with the arrival of dawn, the malign enchantment compels Odette and her companions to return to the lake and they once again assume their swan forms.

Act 3

An opulent hall in the palace

Guests gather at the palace for a grand masquerade ball. Six princesses are introduced to the prince as potential brides [Entrance of the Guests and Waltz]. Rothbart arrives incognito [Scène: Allegro, Allegro giusto] and presents his daughter, Odile, disguised as Odette. Despite the princesses' efforts to charm Siegfried with their dances [Pas de six], his attention remains fixed on Odile. [Scène: Allegro, Tempo di valse, Allegro vivo] Odette appears at the palace window, endeavouring to alert him, but she goes unnoticed. Siegfried then publicly pledges himself to Odile, after which Rothbart conjures a mystical vision of the true Odette. Realising his grievous error, having vowed fidelity only to Odette, he is overwhelmed by despair and hastens back to the lake.

Act 4

By the lakeside

Odette is overwhelmed by sorrow. Her fellow swan maidens offer solace, yet the burden of grief remains. Siegfried returns to the lake, expressing remorse and imploring forgiveness. Odette absolves him, but the consequences of his betrayal are immutable. Rejecting a life bound by the curse, she chooses death over perpetual swanhood. Siegfried resolves to share her fate, and together they plunge into the lake, ensuring their eternal union. This supreme act of devotion shatters Rothbart’s enchantment over the swan maidens, divesting him of his power and bringing about his demise. In a final apotheosis, the maidens, restored to their human forms, witness Siegfried and Odette’s ascent into the Heavens, eternally united by love.

1877 libretto synopsis

Act 1

Prince Siegfried, his companions, and a number of peasants are gathered to celebrate his coming of age. The festivities are lively, marked by dancing and merriment. Siegfried’s mother arrives, expressing her wish that he soon take a wife so as to secure the honour of their family lineage. She announces that a ball has been arranged for him to select a bride from among the daughters of the nobility. After the celebration concludes, Siegfried and his close friend Benno catch sight of a flock of swans in flight, which prompts them to embark upon a hunt.

Act 2

Siegfried and Benno pursue the flock of swans to a lake, only to witness their sudden disappearance. There, they encounter a woman adorned with a crown who introduces herself as Odette, revealing she was one of the swans they sought. She recounts her tale: her mother, a benevolent fairy, had once wed a knight who, upon her death, remarried. Odette’s stepmother, a witch, sought her demise, but her grandfather intervened and saved her. So profound was his grief over her mother’s passing that his tears formed the very lake in which they now dwell. Alongside her companions and grandfather, Odette inhabits this lake, possessing the power to transform at will into a swan. Yet her stepmother, taking the form of an owl, continues to pursue her, though Odette is shielded by a crown that grants protection from harm. The curse shall be broken when Odette marries, as this event will strip her stepmother of her dark power. Siegfried is captivated by Odette, but she remains fearful that her stepmother's malice may spoil their happiness.

Act 3

At Siegfried's ball, several young noblewomen dance, though he declines to choose any as his bride. Baron von Rothbart arrives in disguise, accompanied by his daughter, Odile, who bears a striking resemblance to Odette. While Benno remains unconvinced of the likeness, Siegfried becomes increasingly captivated by Odile as they dance. Ultimately, he declares his intention to marry her. In that moment, Rothbart reveals his true form as a demon, Odile laughs sinisterly, and a white swan crowned with a tiara appears at the window. Overwhelmed, Siegfried flees the castle.

Act 4

In tears, Odette laments that Siegfried has broken his vow of love. Her fellow swan maidens urge her to depart with them upon seeing Siegfried approach, but she insists on seeing him one final time. A storm erupts as Siegfried enters, imploring her forgiveness. She denies him and attempts to leave, whereupon he seizes the crown from her head and casts it into the lake, declaring, "Willing or unwilling, you will always remain with me!" The malevolent owl soars overhead, bearing the crown away. Odette cries out in anguish, "What have you done? I am dying!" and collapses into his arms. The lake, stirred by the tempest, rises and engulfs them both. As the storm subsides, a cluster of swans appears upon the tranquil waters.[64]

Alternative endings

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2022) |

Swan Lake is known for featuring a variety of endings that range from the deeply romantic to the profoundly tragic. Some versions conclude with the lovers’ ultimate sacrifice, uniting in death and breaking the sorcerer’s curse through their sublime love. Other interpretations offer a more optimistic resolution, wherein good triumphs over evil, the villain is defeated, and Odette is restored permanently to human form to live happily with Siegfried. These alternative conclusions reflect diverse artistic visions and cultural contexts, ranging from spiritual transcendence to earthly victory, allowing each production to impart a unique emotional impact on its audience.

- In 1950, Konstantin Sergeyev mounted a new production of Swan Lake for the Mariinsky Ballet (then known as the Kirov Theatre), which drew extensively on the original choreography by Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov. Sergeyev’s staging also incorporated stylistic elements associated with Agrippina Vaganova and Alexander Gorsky, reflecting a synthesis of classical Russian ballet traditions. Notably, during the Soviet era, the ballet's conventionally tragic denouement was altered to reflect ideological preferences, replacing the lovers' tragic deaths with a happier resolution. Consequently, both the Mariinsky and Bolshoi ballet versions concluded with the protagonists Odette and Siegfried united and joyful, an ending designed to align with the regime’s inclination toward optimistic narratives. This 1950 production has since become a defining interpretation of Swan Lake within Russia, celebrated for blending tradition with the political and cultural imperatives of its time.[65][66]

- The version of Swan Lake presently performed by the Mariinsky Ballet concludes with an optimistic "happily ever after" scenario, marking a significant departure from the traditionally tragic endings. In this rendition, Prince Siegfried triumphs over Rothbart in a combat, tearing off the sorcerer’s wing and killing him. Consequently, Odette is restored to her human form, and the lovers are joyfully reunited, symbolising the ultimate victory of good over evil. This resolution reflects the influential 1950 revision by Konstantin Sergeyev, who adapted the original choreography of Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov to incorporate more hopeful themes, in line with Soviet-era artistic directives favouring affirmative conclusions. This interpretation has attained wide acceptance and is frequently adopted not only by the Mariinsky but also by Russian and Chinese ballet companies, underscoring its enduring popularity and cultural resonance. The staging is complemented by opulent costumes and sets that reinforce the narrative’s emotional uplift, while the choreography retains the classical grandeur and virtuosic demands that define the ballet's stature within the international repertoire. This version exemplifies how Swan Lake continues to evolve, balancing tradition with interpretive variations that reflect shifting aesthetic and ideological contexts.[67][68][69][70][71][72]

- Rudolf Nureyev’s 1966 production of Swan Lake for the Vienna State Ballet presents a notably tragic and atmospheric interpretation of the ballet's conclusion. In this version, Rothbart abducts Odette, while Siegfried is left to face the tempestuous storm conjured by the sorcerer. The violent storm consumes Siegfried, resulting in his demise, and Odette remains in captivity, thus concluding the narrative on a profoundly sombre note. Nureyev’s choreography, developed in 1964 and filmed in 1966, is distinguished by its psychological intensity and the collaboration with Margot Fonteyn, who danced the dual role of Odette/Odile. The production’s staging and designs, crafted by Nicholas Georgiadis, contribute to a moody and evocative atmosphere that underscores the themes of loss, power, and entrapment. The interpretation notably diverges from more redemptive conclusions commonly associated with Swan Lake, embracing instead a bleak resolution that highlights the tragic consequences of betrayal and dark magic. This version remains part of the Vienna State Ballet's repertoire and is widely regarded for its artistic significance and the celebrated partnership of Nureyev and Fonteyn.[73][74][75]

- Rudolf Nureyev’s 1986 production of Swan Lake for the Paris Opera Ballet presents a notably sombre and tragic conclusion to the ballet’s narrative. The climactic encounter depicts a fierce confrontation between Prince Siegfried and Rothbart. Despite Siegfried’s valiant efforts, he is ultimately vanquished and succumbs to death. In a striking contrast to earlier interpretations, Rothbart emerges triumphant, aloft with Odette in his grasp, elevating her skyward, thereby signifying his dominion and the lovers’ irrevocable separation. Nureyev’s conception emphasises psychological complexity, repositioning Siegfried as the ballet’s principal dramatic figure, tormented by unfulfilled desire and doomed idealism. This rendition integrates Freudian symbolism and explores the fantastical as an extension of Siegfried’s inner psyche, with the ballet unfolding largely as a dream or fantasy. The staging, notably austere and infused with dark, Gothic atmospheres, departs from traditional romanticism, highlighting themes of repression and fatal destiny. First premiered at the Paris Opera in 1984 and revived in 1986, Nureyev’s version has been recognised for its bold reinterpretation of classical ballet norms, offering a theatrical and psychologically nuanced alternative to more conventional revivals. Despite mixed critical reception, it significantly influenced subsequent stagnings by foregrounding male virtuosity and intensifying the dramatic tension between characters.[76][77][78][79][80][81]

- In the 1988 production of Swan Lake choreographed by Rudi van Dantzig for the Dutch National Ballet, the narrative concludes with a poignant departure from more conventional interpretations. Siegfried comes to the painful realisation that he cannot rescue Odette from Rothbart's curse, leading him to drown himself in despair. His loyal companion, Alexander, discovers Siegfried's lifeless body and carries him ashore. This ending eschews the often romanticised apotheosis, instead offering a sober meditation on loss and unfulfilled ideals. The role of Alexander is notably expanded, providing a compassionate counterpoint to Siegfried’s tragedy and embodying the continuation of his aspirations beyond death. Van Dantzig's choreography, inspired deeply by Tchaikovsky’s writings and music, emphasises emotional depth and psychological nuance throughout the ballet, culminating in this uniquely somber denouement.[82][83][84]

- The 1988 production of Swan Lake by the London Festival Ballet presents a profoundly tragic conclusion. In this version, Odette dies in Siegfried's arms, and he carries her to the lake where they both willingly drown themselves. Their shared sacrifice breaks the sorcerer's curse and unites them in death, a poignant ending that highlights themes of love, loss, and redemption. This interpretation, choreographed with significant contributions from Natalia Makarova, Sir Frederick Ashton, and Marius Petipa, remains a powerful and emotionally charged rendition of the classic ballet.[70][85][86]

- In Yury Grigorovich’s 1969 staging of Swan Lake for the Bolshoi Ballet, the drama concluded with an affirmative resolution broadly consonant with the variant preserved in the Mariinsky Ballet tradition. This ending, in keeping with mid‑twentieth‑century Soviet practice, employed a celebratory Apotheosis in which the forces of good triumph, love is vindicated, and the musical materials are resolved in a major key, underscoring the work’s presentation as a parable of moral clarity. Grigorovich’s 2001 revision, however, introduced a wholly different and notably more sombre conclusion. In this reworking, Siegfried is decisively overcome during his confrontation with the Evil Genius, a role which, in Grigorovich’s dramaturgy, functions less as a conventional sorcerer than as a symbolic embodiment of destructive or fated forces. Odette is seized and carried away into an unspecified, unredeemable realm before she and Siegfried can achieve union, leaving the prince alone and desolate by the lakeside. This dramatic shift is reinforced through corresponding changes to the musical score. The jubilant major‑key treatment of the principal leitmotif, together with the Apotheosis retained in the 1969 version, was excised. In its place Grigorovich adopted a transposed reprise of the sombre Introduction, followed by the closing bars of Numbers 10 and 14 from Tchaikovsky’s score. The result is a finale of markedly elegiac tone, replacing the celebratory resolution with an impression of tragic irresolution and existential futility. This change exemplified the broader interpretative flexibility of Swan Lake, a ballet whose conclusion has never been entirely stabilised in performance history. The canonical 1895 production by Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov for the Imperial Ballet concluded with the lovers’ dual suicide, a resolution viewed both as tragic and as spiritually redemptive, since their sacrifice secured victory over Rothbart and the release of Odette’s companions. Yet in the twentieth century, especially within the Soviet Union, ideological frameworks often demanded a more optimistic or morally didactic outcome, leading to productions in which Siegfried vanquishes evil and love is ultimately triumphant. Grigorovich’s shift in 2001 therefore represents not only a personal artistic revision but also an implicit commentary on the tradition itself: rejecting the imposed optimism of Socialist Realism in favour of a starker, more tragic vision more consistent with the darker undercurrents of Tchaikovsky’s score.[87][88][89][90]

- In the American Ballet Theatre’s production of Swan Lake, first staged in 2000 and preserved in a widely circulated video recording from 2005, the conclusion closely mirrors that of the 1895 Mariinsky revival. Within this interpretation, Prince Siegfried’s ill-fated pledge of fidelity to Odile irrevocably condemns Odette to eternal swan form. Aware that her final moment of humanity draws near, Odette chooses to end her life by casting herself into the lake. Siegfried follows her in death, an act of self-sacrifice that ultimately breaks the sorcerer Rothbart’s dominion, leading to his destruction. The ballet culminates in an apotheosis, wherein the lovers are depicted rising together to Heaven, symbolising transcendence and eternal union. This ending conveys a poignant synthesis of tragedy and redemption, emphasising themes of love’s power as well as sacrifice. Its fidelity to the original Ivanov and Petipa choreography, rooted in the Imperial Russian tradition, distinguishes it from various other modern interpretations that variably opt for more optimistic or ambiguous resolutions. The musical and choreographic framework supports the emotional gravity of the narrative’s final moments, maintaining the integrity of Tchaikovsky’s evocative score while highlighting its dramatic potential for catharsis. By adhering to this classical tragic resolution, American Ballet Theatre’s production offers a historically informed and emotionally resonant conclusion that honours the legacy of the original Swan Lake, as reconstructed by the Mariinsky Ballet in the late nineteenth century.[91][92]

- In the 2006 production of Swan Lake staged by the New York City Ballet, with choreography by Peter Martins drawing upon the works of Lev Ivanov, Marius Petipa, and George Balanchine, the narrative adheres to a markedly tragic trajectory. Within this interpretation, Prince Siegfried’s declaration of intent to marry Odile is perceived as a profound act of betrayal, resulting in the irrevocable condemnation of Odette to remain a swan eternally. As the drama unfolds, Odette is compelled to return to her swan form, departing the human realm and symbolically representing loss and separation. Siegfried is left alone on stage, overwhelmed by grief and isolation, as the curtain falls, underscoring the ballet’s sombre denouement.This version, while incorporating the classical choreographic lineage and Tchaikovsky’s well-known score, emphasises emotional complexity and psychological nuance over traditional romantic resolution. Martins’s choreography synthesises elements inherited from the Imperial Russian tradition and Balanchine’s neoclassical aesthetic, creating a rendition that is both a homage and an innovative reinterpretation. The restrained and poignant conclusion contrasts with other more redemptive endings found in alternative productions, situating this work within a modern discourse on tragic love and the inexorable consequences of fate. By modestly modifying the conclusion in line with the dramatic betrayal at the narrative’s core, the New York City Ballet’s rendition exemplifies how Swan Lake continues to be a dynamic canvas for re-examination and reinterpretation within the contemporary ballet repertoire.[93][94][95]

- In Stanton Welch’s 2006 production of Swan Lake for Houston Ballet, which draws upon the choreographic heritage of Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov, the final scene is marked by a heartrending climax. In this interpretation, Prince Siegfried attempts to slay the malevolent Rothbart with a crossbow, but his arrow misses the intended target and instead strikes Odette. As a result, she collapses; Rothbart’s spell is consequently broken, and Odette is restored to her human form. Siegfried embraces her in a profoundly tragic moment as she succumbs to her wounds. The ballet concludes with Siegfried carrying her lifeless body into the lake before following her into death by drowning. Welch’s production is distinguished by its psychological depth and dramatic intensity, adhering to classical ballet’s narrative core while imbuing it with contemporary sensibilities. The choreography maintains many of the canonical elements that define Swan Lake, yet Welch’s staging accelerates the pacing and heightens emotional realism to resonate with twenty-first-century audiences. This poignant ending conveys themes of tragic love, sacrifice, and the devastating cost of enchantment, aligning with but also subtly reinterpreting the revered Imperial Russian tradition. This version’s emotive resolution reflects Welch’s artistic vision to combine fidelity to the traditional choreography and music with a fresh narrative perspective — presenting Swan Lake as a compelling and cohesive work that continues to evolve in performance today.[96][97][98][99][100]

- In the 2006 production of Swan Lake choreographed by Michael Pink for the Milwaukee Ballet, the narrative adopts a notably dramatic and tragic dimension. In this interpretation, Rothbart inflicts a mortal wound upon Odette in full view of Prince Siegfried. Despite her grievous injury, Siegfried carries Odette to the lakeside, where they ultimately drown together, their shared demise symbolising the triumph of their love over the forces of evil represented by Rothbart and Odile. Consistent with the conclusion of the 1895 Mariinsky revival, the ballet’s final apotheosis depicts the lovers reunited in death, embodying a poignant spiritual transcendence and closure to the drama. Pink’s staging is distinguished by its emphasis on emotional intensity and psychological complexity, offering a fresh yet respectful homage to the classical tradition. The production refrains from romanticising the swans, instead imbuing their plight with somber realism, reflected also in the stripped-back costume design and an underlying political narrative motif. This version reaffirms the enduring resonance of Swan Lake's themes of sacrifice, love, and redemption, within a contemporary choreographic framework.[101][102][103]

- In the San Francisco Ballet’s 2009 production of Swan Lake, choreographed by Artistic Director Helgi Tomasson, the climax closely follows the 1895 Mariinsky revival’s tragic resolution. Prince Siegfried and Odette, unable to overcome the dark forces arrayed against them, choose to throw themselves into the lake, drowning together. This ultimate act of love and sacrifice leads to the destruction of Rothbart’s evil influence. The ballet concludes with a symbolic tableau in which two swans, implicitly representing the reunited lovers, are seen soaring past the Moon, evoking themes of spiritual transcendence and eternal union. Tomasson’s version integrates a modern sensibility with the ballet’s classical heritage, exemplified by contemporary yet elegant set and costume designs by Jonathan Fensom that deepen the narrative’s psychological and symbolic dimensions. His revised choreography respects the traditional structure, while enhancing narrative coherence and dramatic impact through the connection of acts and the repositioning of key scenes. This production remains a distinguished and popular interpretation within the repertoire of the San Francisco Ballet, reflecting both the enduring power of Swan Lake and its capacity for continual artistic renewal.[104][105][106]

- In the 2010 production of Swan Lake performed by the National Ballet of Canada, Odette exhibits forgiveness towards Siegfried despite his earlier betrayal, intimating a fragile promise of reconciliation. This moment of hope is swiftly shattered when Rothbart conjures a violent storm, prompting a fierce struggle between the sorcerer and Siegfried. As the tempest subsides, Odette is left alone on stage to mourn the fallen Siegfried, underscoring the ballet’s tragic dimension and the enduring theme of loss. This interpretation, influenced by choreographic innovations introduced by James Kudelka and staged under the artistic vision of Karen Kain, departs from more traditional renditions by placing greater emphasis on emotional complexity and character psychology. The production subtly downplays the mythical and fairy-tale elements, favouring a nuanced exploration of love, betrayal, and grief within a brooding, atmospheric setting. Costume and set designs contribute richly to this ambience, situating the narrative in an ambiguous historical European context that reinforces the universality of its themes.[107][108][109][110]

- In the 2012 version performed at Blackpool Grand Theatre by the Russian State Ballet of Siberia Siegfried drags Rothbart into the lake and they both drown. Odette is left as a swan.[111][112][113]

- In the 2015 English National Ballet version My First Swan Lake, specifically recreated for young children, the power of Siegfried and Odette's love enables the other swans to rise up and defeat Rothbart, who falls to his death. This breaks the curse, and Siegfried and Odette live happily ever after. This is like the Mariinsky Ballet's "happily ever after" endings. In a new production in 2018, Odile helps Siegfried and Odette in the end. Rothbart, who is Odile's brother in this production, is forgiven and he gives up his evil power. Odette and Siegfried live happily ever after and stay friends with Rothbart and Odile.[114][115]

- In Hübbe and Schandorff's 2015 and 2016 Royal Danish Ballet production, Siegfried is forced by Rothbart to marry Odile, after condemning Odette to her curse as a swan forever by mistakenly professing his love to Odile.

- In the 2018 Royal Ballet version, Siegfried rescues Odette from the lake, but she turns out to be dead, even though the spell is broken. The pre-2018 versions do not have this ending, only the 1895 ending.[116]

- In David Hallberg's 2023 Australian Ballet version, Odette makes an irrevocable promise to von Rothbart, vowing eternal obedience in order to save Siegfried. Triumphantly, Rothbart takes Odette away from Siegfried. Alone in his grief, Siegfried throws himself off a cliff and dies.[117]

Remove ads

Structure

Summarize

Perspective

Tchaikovsky’s original score for Swan Lake, including the additional music composed for the initial 1877 production,[118] which differs from the revised version by Riccardo Drigo created for the revival by Petipa and Ivanov and still employed by most ballet companies, follows this structure. The titles assigned to each musical number are taken from the original published score. While some numbers bear purely musical designations, those with titles have been translated from their original French.

Act 1

Introduction: Moderato assai – Allegro non-troppo – Tempo I

- No. 1 Scène: Allegro giusto

- No. 2 Waltz: Tempo di valse

- No. 3 Scène: Allegro moderato

- No. 4 Pas de trois

- Intrada (or Entrée): Allegro

- Andante sostenuto

- Allegro semplice, Presto

- Moderato

- Allegro

- Coda: Allegro vivace

- No. 5 Pas de deux for Two Merry-makers (later fashioned into the Black Swan Pas de Deux)

- Tempo di valse ma non troppo vivo, quasi moderato

- Andante – Allegro

- Tempo di valse

- Coda: Allegro molto vivace

- No. 6 Pas d'action: Andantino quasi moderato – Allegro

- No. 7 Sujet (Introduction to the Dance with Goblets)

- No. 8 Dance with Goblets: Tempo di polacca

- No. 9 Finale: Sujet, Andante

Act 2

- No. 10 Scène: Moderato

- No. 11 Scène: Allegro moderato, Moderato, Allegro vivo

- No. 12 Scène: Allegro, Moderato assai quasi andante

- No. 13 Dances of the Swans

- Tempo di valse

- Moderato assai

- Tempo di valse

- Allegro moderato (later the famous Dance of the Little Swans)

- Pas d'action: Andante, Andante non-troppo, Allegro (material borrowed from Undina)

- Tempo di valse

- Coda: Allegro vivo

- No. 14 Scène: Moderato

Act 3

- No. 15 Scène: March – Allegro giusto

- No. 16 Ballabile: Dance of the Corps de Ballet and the Dwarves: Moderato assai, Allegro vivo

- No. 17 Entrance of the Guests and Waltz: Allegro, Tempo di valse

- No. 18 Scène: Allegro, Allegro giusto

- No. 19 Pas de six

- Intrada (or Entrée): Moderato assai

- Variation I: Allegro

- Variation II: Although bearing the designation Andante con moto and formally presented as a variation, this number was most likely conceived to follow the Intrada, functioning as the central Grande adage of the Pas de six. Its placement, however, appears to have been either originally conceived out of sequence or subsequently altered in publication, where it was issued in the guise of a variation immediately after the first.

- Variation III: Moderato

- Variation IV: Allegro

- Variation V: Moderato, Allegro semplice

- Grand Coda: Allegro molto

- Appendix I – Pas de deux pour Mme. Anna Sobeshchanskaya[a]

- Andante

- Variation I: Allegro moderato

- Variation II: Allegro

- Coda: Allegro molto vivace

- No. 20 Hungarian Dance: Czardas – Moderato assai, Allegro moderato, Vivace

- Appendix II – No. 20a Danse russe pour Mlle. Pelageya Karpakova: Moderato, Andante semplice, Allegro vivo, Presto

- No. 21 Danse Espagnole: Allegro non-troppo (Tempo di bolero)

- No. 22 Danse Napolitaine: Allegro moderato, Andantino quasi moderato, Presto

- No. 23 Mazurka: Tempo di mazurka

- No. 24 Scène: Allegro, Tempo di valse, Allegro vivo

Act 4

- No. 25 Entr'acte: Moderato

- No. 26 Scène: Allegro non-troppo

- No. 27 Dance of the Little Swans: Moderato

- No. 28 Scène: Allegro agitato, Molto meno mosso, Allegro vivace

- No. 29 Scène finale: Andante, Allegro, Alla breve, Moderato e maestoso, Moderato

Remove ads

Adaptations and references

Live-action film

- Darren Aronofsky's Black Swan (2010) focuses on two characters from Swan Lake-the Princess Odette, sometimes called the White Swan, and her evil duplicate, the witch Odile (the Black Swan), and takes its inspiration from the ballet's story, although it does not literally follow it. Clint Mansell's score contains music from the ballet, with more elaborate restructuring to fit the horror tone of the film.[121][122]

Animated films

- Swan Lake (1981) is a feature-length anime produced by the Japanese company Toei Animation and directed by Koro Yabuki. The adaptation uses Tchaikovsky's score and remains relatively faithful to the story. Two separate English dubs were made, one featuring regular voice actors, and one using celebrities as the main principals (Pam Dawber as Odette, Christopher Atkins as Siegfried, David Hemmings as Rothbart, and Kay Lenz as Odille). The second dub was recorded at Golden Sync Studios and aired on American Movie Classics in December 1990 and The Disney Channel in January 1994.[123] It was presently distributed in the United States by The Samuel Goldwyn Company. It was also distributed in France and the United Kingdom by Rouge Citron Production.[124]

- Swan Lake (1994) is a 28-minute traditional two-dimensional animation narrated by Dudley Moore. It is one of five animations in the Storyteller's Classics series. Like the 1981 version, it also uses Tchaikovsky's music throughout and is quite faithful to the original story. What sets it apart is the climactic scene, in which the prince swims across the lagoon towards Rothbart's castle to rescue Odette, who is being held prisoner there. Rothbart points his finger at the prince and zaps him to turn him into a duck – but then, the narrator declares, "Sometimes, even magic can go very, very wrong." After a moment, the duck turns into an eagle and flies into Rothbart's castle, where the prince resumes his human form and engages Rothbart in battle. This animation was produced by Madman Movies for Castle Communications. The director was Chris Randall, the producer was Bob Burrows, the production co-ordinator was Lesley Evans and the executive producers were Terry Shand and Geoff Kempin. The music was performed by the Moscow State Orchestra. It was shown on TVOntario in December 1997 and was distributed on home video in North America by Castle Vision International, Orion Home Video and J.L. Bowerbank & Associates.

- The Swan Princess (1994) is a Nest Entertainment film based on the Swan Lake story. It stays fairly close to the original story, but does contain many differences. For example, instead of the Swan Maidens, we have the addition of sidekicks Puffin the puffin, Speed the tortoise, and Jean-Bob the frog. Several of the characters are renamed – Prince Derek instead of Siegfried, his friend Bromley instead of Benno and his tutor Rogers instead of Wolfgang; Derek's mother is named Queen Uberta. Another difference is Odette and Derek knowing each other from when they were children, which introduces us to Odette's father, King William and explains how and why Odette is kidnapped by Rothbart. The character Odile is replaced by an old hag (unnamed in this movie, but known as Bridget in the sequels), as Rothbart's sidekick until the end. Also, this version contains a happy ending, allowing both Odette and Derek to survive as humans once Rothbart is defeated. It has eleven sequels, Escape from Castle Mountain (1997), The Mystery of the Enchanted Treasure (1998), Christmas (2012), A Royal Family Tale (2014), Princess Tomorrow, Pirate Today (2016), Royally Undercover (2017), A Royal MyZtery (2018), Kingdom of Music (2019), A Royal Wedding (2020), A Fairytale is Born (2023), and Far Longer than Forever (2023) which deviate even further from the ballet. None of the films contain Tchaikovsky's music.

- Barbie of Swan Lake (2003) is a direct-to-video children's movie featuring Tchaikovsky's music and motion capture from the New York City Ballet and based on the Swan Lake story. In this version, Odette is not a princess by birth, but a baker's daughter; instead of being kidnapped by Rothbart and taken to the lake against her will, she discovers the Enchanted Forest when she willingly follows a unicorn there. She is also made into a more dominant heroine in this version, as she is declared as the one who is destined to save the forest from Rothbart's clutches when she frees a magic crystal. Another difference is the addition of new characters, such as Rothbart's cousin the Fairy Queen, Lila the unicorn, Erasmus the troll, and the Fairy Queen's fairies and elves, who have also been turned into animals by Rothbart. These fairies and elves replace the Swan Maidens from the ballet. In this version, Rothbart does not even refer to Odette by name, except once when he referred to her as "That Silly Odette Girl". It is also the Fairy Queen's magic that allows Odette to return to her human form at night, not Rothbart's spell. Other changes include renaming the Prince Daniel and a happy ending, instead of the ballet's tragic ending. Like the 1877 production, Odette wears a magic crown that protects her.

Dance

- The Swedish dancer/choreographer Fredrik Rydman has produced a modern dance/street dance interpretation of the ballet entitled Swan Lake Reloaded. It depicts the "swans" as heroin addict prostitutes who are kept in place by Rothbart, their pimp. The production's music uses themes and melodies from Tchaikovsky's score and incorporates them into hip-hop and techno tunes.[125]

Literature

- Amiri & Odette (2009) is a verse retelling by Walter Dean Myers with illustrations by Javaka Steptoe.[126] Myers sets the story in the Swan Lake Projects of a large city. Amiri is a basketball-playing "Prince of the Night", a champion of the asphalt courts in the park. Odette belongs to Big Red, a dealer, a power on the streets.

- The Black Swan (1999) by Mercedes Lackey is a fantasy novel that retells the Swan Lake story from the perspective of Odile, the sorcerer Baron von Rothbart’s daughter. Odile, trained in magic, initially serves her father’s mission to curse women who have supposedly betrayed men by transforming them into swans by day. Over time, she grows sympathetic to the captive maidens, especially their leader, Odette. When von Rothbart uses Odile to deceive Prince Siegfried and break his vow to Odette, Odile ultimately rebels against her father, using her magic to defeat him.[127][128][129]

- Swan Lake (1989), authored by Mark Helprin and illustrated by Chris Van Allsburg, is a reinterpretation of the classical ballet framed within a narrative of political upheaval in an unspecified Eastern European context. The novel employs a narrative structure presenting the story as recounted by an elder to a young girl, central to the plot is Odette, a princess hidden from birth to safeguard her from a puppetmaster who controls the throne. Van Allsburg’s illustrations complement the text with imagery that deepens the novel’s atmospheric and allegorical dimensions.[130][131]

Television

- In episode 213 (Season 2, Episode 13) of The Muppet Show, Rudolf Nureyev appeared in a ballet parody titled "Swine Lake."[132][133]

Musicals or opera

- Odette – The Dark Side of Swan Lake, a musical written by Alexander S. Bermange and Murray Woodfield, was staged at the Bridewell Theatre, London in October 2007.

- In Radio City Christmas Spectacular, The Rockettes do a short homage to Swan Lake during the performance of the "Twelve Days of Christmas (Rock and Dance Version)", with the line "Seven Swans A-Swimming"

Remove ads

Selected discography

Audio

Video

Remove ads

References

Notes

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads