Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Akrasia

Lack of self-control From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Akrasia[a] refers to the phenomenon of acting against one's better judgment—the state in which one intentionally performs an action while simultaneously believing that a different course of action would be better.[1][2] Sometimes translated as "weakness of will" or "incontinence," akrasia describes the paradoxical human experience of knowingly choosing what one judges to be the inferior option.

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

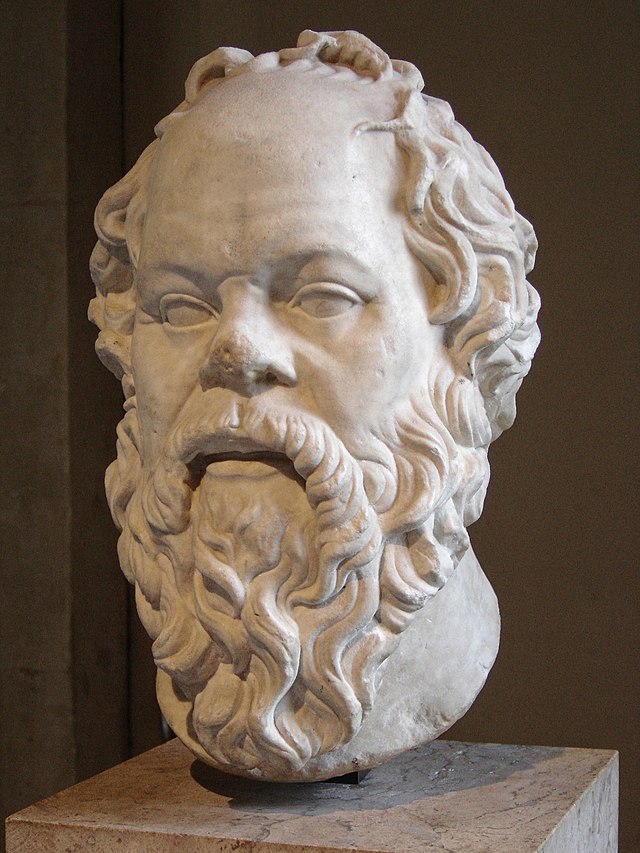

In Plato's Protagoras dialogue, Socrates asks precisely how it is possible that, if one judges action A to be the best course of action, why one would do anything other than A.[3]

Classical answers

In Plato's Protagoras, Socrates presents a radical thesis that fundamentally denies the existence of akrasia. His famous declaration, "No one goes willingly toward the bad" (οὐδεὶς ἑκὼν κακός), encapsulates a view known as Socratic intellectualism.[4]

According to Socrates, genuine akrasia is impossible because human action necessarily follows knowledge. His argument proceeds through several interconnected premises:

- The Unity of Knowledge and Virtue: Socrates maintains that virtue is knowledge. Specifically, virtue is knowledge of what is truly good and beneficial. To know the good is necessarily to pursue it, as knowledge compels action.[5]

- The Natural Orientation Toward the Good: Human beings, by their very nature, seek what they perceive to be good for themselves. No rational agent deliberately chooses what they genuinely believe to be harmful or inferior to available alternatives.[6][7]

- The Power of Complete Knowledge: When one conducts a thorough, all-things-considered evaluation of a situation, this assessment yields complete knowledge of each potential action's outcomes and relative worth. This knowledge is inextricably linked to well-developed principles of the good.

Given the above premises, Socrates concludes that it is psychologically impossible for someone who truly knows what is best to act otherwise. The person who possesses genuine knowledge of the good will inevitably pursue it, as this pursuit aligns with both human nature and rational necessity.

Therefore, in the Socratic framework, what appears to be akrasia—acting against one's better judgment—is actually a form of ignorance. Actions that seem to contradict what is objectively best must result from incomplete knowledge of the facts, inadequate understanding of what constitutes the genuine good, or failure to properly calculate the consequences of one's actions.

Aristotle recognizes that the possibility of acting contrary to one's best judgment is a staple of commonsense and a common human experience.[8] Aristotle dedicates Book VII of the Nicomachean Ethics to an examination of akrasia, adopting a distinctly empirical approach that contrasts sharply with Socratic intellectualism.[9] He distanced himself from the Socratic position by distinguishing different mental faculties and their roles in action. He argues that akrasia results from the one's opinion (δόξα, doxa), not one's desire (epithumia) per se. The crucial difference here is that while desire is a natural condition of the body incapable of truth or falsity, opinion is a belief that may or may not be true, a cognitive state. Therefore, akratic failures can be explained by the incorrectness of one's best judgment rather than a failure to attempt to act according to one's best judgment. When an agent's best judgment is a false belief, it does not have the power to compel one that Socrates attributed to knowledge of what is genuinely best.

For Aristotle, the opposite of akrasia is enkrateia, a state where an agent has power over their desires.[10] Aristotle considered one could be in a state of akrasia with respect to money or temper or glory, but that its core relation was to bodily enjoyment.[11] Its causes could be weakness of will, or an impetuous refusal to think.[12] At the same time he did not consider it a vice because it is not so much a product of moral choice as a failure to act on one's better knowledge.[13]

For Augustine of Hippo, incontinence was not so much a problem of knowledge but of the will; he considered it a matter of everyday experience that men incontinently choose lesser over greater goods.[14]

Contemporary approaches

Donald Davidson attempted to answer the question by first criticizing earlier thinkers who wanted to limit the scope of akrasia to agents who despite having reached a rational decision were somehow swerved off their "desired" tracks. Indeed, Davidson expands akrasia to include any judgment that is reached but not fulfilled, whether it be as a result of an opinion, a real or imagined good, or a moral belief. "[T]he puzzle I shall discuss depends only on the attitude or belief of the agent...my subject concerns evaluative judgments, whether they are analyzed cognitively, prescriptively, or otherwise." Thus, he expands akrasia to include cases in which the agent seeks to fulfill desires, for example, but end up denying themselves the pleasure they have deemed most choice-worthy.

Davidson sees the problem as one of reconciling the following apparently inconsistent triad:

- If an agent believes A to be better than B, then they want to do A more than B.

- If an agent wants to do A more than B, then they will do A rather than B if they only do one.

- Sometimes an agent acts against their better judgment.

Davidson solves the problem by saying that, when people act in this way they temporarily believe that the worse course of action is better because they have not made an all-things-considered judgment but only a judgment based on a subset of possible considerations.

Another contemporary philosopher, Amélie Rorty, has tackled the problem by distilling out akrasia's many forms. She contends that akrasia is manifested in different stages of the practical reasoning process. She enumerates four types of akrasia: akrasia of direction or aim, of interpretation, of irrationality, and of character. She separates the practical reasoning process into four steps, showing the breakdown that may occur between each step and how each constitutes an akratic state.

Another explanation is that there are different forms of motivation that can conflict with each other. Throughout the ages, many have identified a conflict between reason and emotion, which might make it possible to believe that one should do A rather than B, but still end up wanting to do B more than A.

Psychologist George Ainslie argues that akrasia results from the empirically verified phenomenon of hyperbolic discounting, which causes us to make different judgments close to a reward than we will when further from it.[15]

Weakness of will

Richard Holton argues that weakness of the will involves revising one's resolutions too easily. Under this view, it is possible to act against one's better judgment (that is, be akratic) without being weak-willed. Suppose, for example, Sarah judges that taking revenge upon a murderer is not the best course of action but makes the resolution to take revenge anyway and sticks to that resolution. According to Holton, Sarah behaves akratically but does not show weakness of will.

Remove ads

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

In the structural division of Dante's Inferno, incontinence is the sin punished in the second through fifth circles.[16] The mutual incontinence of lust was for Dante the lightest of the deadly sins,[17] even if its lack of self-control would open the road to deeper layers of Hell.

Akrasia appeared later as a character in Spenser's The Faerie Queene, representing the incontinence of lust, followed in the next canto by a study of that of anger;[18] and as late as Jane Austen the sensibility of such figures as Marianne Dashwood would be treated as a form of (spiritual) incontinence.[19]

But with the triumph of Romanticism, the incontinent choice of feeling over reason became increasingly valorised in Western culture.[20] Blake wrote, "those who restrain desire, do so because theirs is weak enough to be restrained".[21] Encouraged by Rousseau, there was a rise of what Arnold J. Toynbee called "an abandon (ακρατεια)...a state of mind in which antinomianism is accepted—consciously or unconsciously, in theory or in practice—as a substitute for creativeness".[22]

A peak of such akrasia was perhaps reached in the 1960s cult of letting it all hang out—of breakdown, acting out, and emotional self-indulgence and drama.[23] Partly in reaction, the proponents of emotional intelligence looked back to Aristotle in the search for impulse control and delayed gratification[24]—to his dictum that "a person is called continent or incontinent according as his reason is or is not in control".[25]

Remove ads

See also

- Aboulia – Neurological symptom of lack of will or initiative

- Acedia – Mental state

- Categorical imperative – Central concept in Kantian moral philosophy

- Disorders of diminished motivation – Group of psychiatric and neurological conditions

- Ego depletion – Psychological theory

- Executive functions – Cognitive processes necessary for control of behavior

- Marshmallow test – Study on delayed gratification by psychologist Walter Mischel

- Higher-order volition – Philosophical term

- Procrastination – Avoiding doing a task that needs to be completed

- Self control – Aspect of inhibitory control

- Velleity – Lowest degree of volition

Footnotes

- /əˈkreɪʒə, -zi-/, ə-KRAY-zhə, -zee-; from Ancient Greek ἀκρασία, literally "lack of self-control" or "powerlessness," derived from ἀ- "without" + κράτος "power, rule"

Notes

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads