Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Sorbian languages

West Slavic language group From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The Sorbian languages[1] (Upper Sorbian: serbska rěč, Lower Sorbian: serbska rěc) are the Upper Sorbian language and Lower Sorbian language, two closely related and partially mutually intelligible languages spoken by the Sorbs, a West Slavic ethno-cultural minority in the Lusatia region of Eastern Germany.[1][2][3] They are classified under the West Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages and are therefore closely related to the other two West Slavic subgroups: Lechitic and Czech–Slovak.[4] Historically, the languages have also been known as Wendish (named after the Wends, the earliest Slavic people in modern Poland and Germany) or Lusatian.[1] Their collective ISO 639-2 code is wen.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2011) |

The two Sorbian languages, each having its own literary standard, are Upper Sorbian (hornjoserbsce), spoken by about 20,000–25,000[5] people in Saxony, and Lower Sorbian (dolnoserbski), spoken by about 7,000 people in Brandenburg. The area where the two languages are spoken is known as Lusatia (Łužica in Upper Sorbian, Łužyca in Lower Sorbian, or Lausitz in German).[1][2][3]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

After the settlement of the formerly Germanic territories (the part largely corresponding to the former East Germany)[3] by the Slavic ancestors of the Sorbs in the 5th and 6th centuries CE,[2] the Sorbian language (or its predecessors) had been in use in much of what was the southern half of Eastern Germany for several centuries. The language still had its stronghold in (Upper and Lower) Lusatia,[2] where it enjoys national protection and fostering to the present day. For people living in the medieval Northern Holy Roman Empire and its precursors, especially for the Saxons, the Wends (Wende) were heterogeneous groups and tribes of Slavic peoples living near Germanic settlement areas, in the area west of the River Oder, an area later entitled Germania Slavica, settled by the Polabian Slav tribes in the north and by others, such as the Sorbs and the Milceni, further south (see Sorbian March).

The exact origin of the Sorbian language is uncertain. While some linguists consider it to be a transitory language between Lechitic and other non-Lechitic languages of West Slavic languages, others like Heinz Schuster-Šewc consider it a separate dialectical group of Proto-Slavic which is a mixture of Proto-Lechitic and South Slavic languages.[6] According to him, "Sorbian spoken today in Upper and Lower Lusatia is what remains of an earlier extensive Old Sorbian dialect area between the Elbe/Saale rivers in the west and the Bober/Queis rivers in the east".[6]

Furthermore, while some consider it a single language which later diverged to two major dialects, others consider these dialects two separate languages. There exist significant differences in phonology, morphology, and lexicon between them. Several characteristics in Upper Sorbian language indicate a close proximity to Czech language which again are absent in Lower Sorbian language.[7] The Upper Sorbian is considered as representative of the old "Sorbian proper", while the Lower Sorbian would be a transitional hybrid language more akin to the Lechitic languages.[6] According to some researchers the archaeological data cannot confirm the thesis about a single linguistic group yet supports the claim about two separated ethno-cultural groups with different ancestry whose respective territories correspond to Tornow-type ceramics (Lower Sorbian language) and Leipzig-type ceramics (Upper Sorbian language),[7] both derivations of Prague culture.[8]

Outside Lusatia, the Sorbian language has been superseded by German. From the 13th century on, the language suffered official discrimination.[4] Bible translations into Sorbian provided the foundations for its writing system.

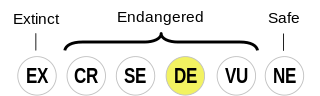

Today, around 60,000 Sorbs live in Germany, about 40,000 in Saxony and 20,000 in Brandenburg. Since national affiliation is not officially recorded in Germany, and identification with the Sorbian nationality is voluntary, the exact number is only an estimate. The number of active Sorbian speakers is likely lower. Unlike Upper Sorbian, Lower Sorbian is considered critically endangered. According to projections, around 7,000 people actively speak Lower Sorbian, which could become extinct within 20 to 30 years, while around 13,000 speak Upper Sorbian. According to language experts,[who?] Upper Sorbian is expected to survive into the 21st century.[citation needed]

Currently, Sorbian is taught at 25 primary schools and several secondary schools. At the Lower Sorbian Gymnasium in Cottbus and the Upper Sorbian Gymnasium in Bautzen, it is compulsory. In many primary and Sorbian schools, lessons are held in the Sorbian language. The daily newspaper Serbske Nowiny is published in Upper Sorbian, and the weekly Nowy Casnik in Lower Sorbian. In addition, the religious weekly journals Katolski Posoł and Pomhaj Bóh are published. The cultural magazine Rozhlad appears monthly, along with one children's magazine each in Upper and Lower Sorbian (Płomjo and Płomje, respectively), as well as the educational magazine Serbska šula.

Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk (MDR) and Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg (RBB) also broadcast monthly half-hour TV magazines in Sorbian, as well as several hours of daily radio programming—the Sorbian radio. Wikipedia editions exist in both written forms of the Sorbian language.

- Upper Sorbian-German information sign in Nebelschütz

- Bilingual street signs in Cottbus (Chóśebuz) in German and Lower Sorbian

- Bilingual town sign in Bautzen (Budyšin) with Upper Sorbian

- Bilingual street sign in Bautzen with Upper Sorbian

- Bilingual information board on the A13

Remove ads

Geographic distribution

Summarize

Perspective

In Germany, Upper and Lower Sorbian are officially recognized and protected as minority languages.[9] In the officially defined Sorbian settlement area, both languages are recognized as second official languages next to German.[10]

The city of Bautzen in Upper Lusatia is the centre of Upper Sorbian culture. Bilingual signs can be seen around the city, including the name of the city, "Bautzen/Budyšin". To the north, the city of Cottbus/Chóśebuz is considered the cultural centre of Lower Sorbian; there, too, bilingual signs are found.

Sorbian was also spoken in the small Sorbian ("Wendish") settlement of Serbin in Lee County, Texas, however no speakers remain there. Until 1949, newspapers were published in Sorbian. The local dialect was heavily influenced by surrounding speakers of German and English.

The German terms "Wends" (Wenden) and "Wendish" (wendisch/Wendisch) once denoted "Slav(ic)" generally;[citation needed] they are today mostly replaced by "Sorbs" (Sorben) and "Sorbian" (sorbisch/Sorbisch) with reference to Sorbian communities in Germany.[citation needed]

Endangered status

The use of Sorbian languages has been contracting for a number of years. The loss of Sorbian language use in emigrant communities, such as in Serbin, Texas, has not been surprising. But within the Sorbian homelands, there has also been a decrease in Sorbian identity and language use. In 2008, Sorbs protested three kinds of pressures against Sorbs: "(1.) the destruction of Sorbian and German-Sorbian villages as a result of lignite mining; (2.) the cuts in the network of Sorbian schools in Saxony; (3.) the reduction of financial resources for the Sorbian institutions by central government."[11]

A study of Upper Sorbian found a number of trends that go against language vitality. There are policies that have led to "unstable diglossia". There has been a loss of language domains in which speakers have the option to use either language, and there is a disruption of the patterns by which the Sorbian language has traditionally been transmitted to the next generation. Also, there is no strong written tradition and there is not a broadly accepted formal standardized form of the language(s). There is a perception of the loss of language rights, and there are negative attitudes towards the languages and their speakers.[12]

Remove ads

Linguistic features

Summarize

Perspective

Both Upper and Lower Sorbian have the dual for nouns, pronouns, adjectives, and verbs; very few living Indo-European languages retain this as a productive feature of the grammar. For example, the word ruka is used for one hand, ruce for two hands, and ruki for more than two hands. As with most Slavic languages, Sorbian uses no articles.

Grammar

The Sorbian languages are declined in six or seven cases:

- Nominative

- Accusative

- Genitive

- Dative

- Locative

- Instrumental

- Vocative (Upper Sorbian only)

In Lower Sorbian, the vocative is preserved only in a few fossilized forms.

Notably, in addition to the singular and plural, the dual number (used for two items), inherited from Old Slavic, has also been preserved.

- Singular: ruka ("hand")

- Dual: ruce ("two hands")

- Plural: ruki ("more than two hands")

In contrast to other West Slavic languages (Czech, Slovak, Polish, Kashubian), Upper Sorbian literary language and some dialects have preserved the synthetic past tense (aorist, imperfect) to this day. This form was also common in Lower Sorbian literary language, but over the course of the 20th century, it has become increasingly rare and is hardly used today.

Lower Sorbian, however, has retained the supine (a variant of the infinitive used after verbs of motion), e.g.: njok spaś ("I don't want to sleep") versus źi spat ("go to sleep")

Less demanding written texts in Sorbian can generally be understood by speakers of West Slavic languages.

Vocabulary comparison

The following is selected vocabulary from the two Sorbian languages compared with other Slavic languages.

Differences between the two written languages

There are several differences between the two written languages, Upper Sorbian and Lower Sorbian, particularly in the alphabet.

Phonetic differences

In the consonants

The two written languages differ significantly in terms of consonants. For example, the letter ć has been alphabetically placed after č in Upper Sorbian since 2005.

Vowels

Both Lower Sorbian and Upper Sorbian have eight vowels.

Different number of syllables

In some words, the number of syllables differs because Upper Sorbian has shortened them here, similarly to Czech.

Differences in declension

Upper Sorbian have seven cases and Lower Sorbian have six cases.

Differences in case government (i.e., which case follows which preposition or verb)

Differences in gender

Differences in conjugation

Differences in vocabulary

Remove ads

Similarities

Summarize

Perspective

Phonetic Similarities

Consonantal Parallels

Vocalic Parallels

Grammatical Similarities

- Preservation of the dual (grammatical number for two items)

- Merger of the locative dual with the dative/instrumental dual

- Stress on the first syllable

- Broad generalization of the genitive plural ending -ow for nouns

Remove ads

Phonological development of Sorbian

Summarize

Perspective

Common developments and developments only in Lower Sorbian

As in Polish and Czech, the two Proto-Slavic reduced vowels ь and ъ in Sorbian developed early into e in stressed position. Full vowels, which stood in syllables before a reduced vowel in unstressed position, were lengthened after the fall of the reduced vowels. Over time, the opposition of short and long vowels was lost, and words were generally stressed on the first syllable; in Proto-Slavic the stress had been free. This development occurred under the influence of German and has a parallel in Czech.

The nasal vowels in Sorbian disappeared according to Jerzy Nalepa in the second half of the 12th century under Czech influence.

The affricate ʒ was, as in most other Slavic languages, simplified to z, cf. mjeza (Polish: miedza) (“border”).

As in Polish and originally also in Kashubian, the soft dentals ť and ď in Sorbian changed into the affricates ć and dź. This transition already occurred in the 13th century. In Lower Sorbian, these affricates later also lost their plosive component: ć > ś, dź > ź, except after dental spirants: rjeśaz “chain”, daś “to give”, kosć “bone”, źiwy “wild”, měź “copper”, pozdźej “later” (compared to Upper Sorbian rjećaz, dać, kosć, diźwi, mjedź, pozdźe). This change occurred in the mid-16th century in the western dialects and 100 years later in the eastern dialects, whereby the central transitional dialects as well as the dialects of Muskau and Schleife were not affected.

Soft c', z', s' were hardened in Sorbian. When the sound i followed them, it changed to y: ducy “to go”, syła “strength”, zyma “winter” (compared to Czech jdoucí, síla, zima). This change probably took place in the early 15th century. A similar change (only in Lower Sorbian) occurred at the beginning of the 16th century with the soft č', ž', š': cysty “clean”, šyja “neck”, žywy “alive” (cf. Upper Sorbian čisty, šija, žiwy).

In the mid-16th century, č became c: cas “time”, pcoła “bee” (from čas, pčoła). This change did not occur only in the ending -učki and after spirants. In addition, č appears in loanwords and onomatopoeic words.

After p, t, and k, the sounds r and r' in Sorbian became ř and ř'. In Lower Sorbian, ř developed further to š and ř' to ć (later ś): pšawy “right”, tśi “three”.

As in Polish, the voiceless ł in Lower Sorbian became bilabial w, with the first written records dating from the 17th century, and the soft ľ adopted the “European” alveolar articulation (as in German) except before front vowels.

The sound w in Sorbian disappeared in initial clusters gw- and xw- (Proto-Slavic gvozdj > gozd “dry forest”, Proto-Slavic xvoščj > chošć “horsetail”), at the beginning of a word before a consonant, and after a consonant before u. This process probably began before the 13th century and ended in the 16th century. The soft “w” in the middle of words in intervocalic position and before consonants as well as at the end of words changed to “j”: rukajca “glove” (Polish: rękawica), mužoju / mužeju “man” (Polish: mężowi), kšej “blood” (Polish: krew).

The sound e changed into a in the position after soft consonants and before hard consonants: brjaza “birch”, kolaso “wheel”, pjac “oven”, lažaś “lie”, pjas “dog” (cf. brěza, koleso, pjec, ležeć', pos). This change was completed in the mid-17th century and again did not affect the dialects of Muskau and Schleife.

Phonological developments Only in Upper Sorbian

In some positions, metathesis of or, ol, er, and el occurred in Upper Sorbian: in positions between consonants, these became ro, lo, re, and le, while at the beginning of a word, or, ol became either ra-, la- or ro-, lo- depending on the stress.

As in Polish and Czech, the two Proto-Slavic reduced vowels in stressed position changed to e in Sorbian as well. Unstressed full vowels in the syllable before the reduced vowel were lengthened with the disappearance of the reduced vowels. Long ē and ō in stressed position became mid vowels in Upper Sorbian, which are written in the modern Upper Sorbian literary language as ě and ó. Proto-Slavic ē merged with ě. Later, in the 19th century, ó became o before reflexive pronouns and labials: mloko – w mlóce (“milk” – “in milk”). Over time, the contrast between long and short vowels was lost.

Syllabic ṛ became or in Upper Sorbian: *kъrmiti > kṛmiti > kormić (“to feed”), and similarly, ṛʼ before voiceless dentals also became or: *pьrstъ > pṛʼstъ > porst (“finger”), while in other positions it softened to je: *prštěp > pṛʼštěp > pjeršćeń (“ring”). Syllabic ḷ became oł: *dъlgъ > dḷgъ > dołh (“debt”), or before voiceless dentals became ḷʼ: *rlnj > pḷʼpъ > połny (“full”), and in other positions became el: *vjlk > vḷʼkъ > wjelk (“wolf”).

The nasal vowels in Sorbian disappeared, according to J. Nalepa, in the second half of the 12th century under Czech influence, while in Polish they remain to this day. The vowel a between two soft consonants became e in Upper Sorbian: jeje (“egg”), žel (“compassion”). Written evidence suggests this occurred in the 17th and 18th centuries, and in some Upper Sorbian dialects, it has not occurred at all.

Just as in Czech, Slovak, and Ukrainian, the plosive g turned into the fricative h in Upper Sorbian. The g sound only appears in relatively recent loanwords or expressive words in Upper Sorbian. J. Nalepa dates the beginning of the shift g > h to the late 13th century, while J. Stone places it in the 12th century, stating that the change spread from south to north. Gunter Schaarschmidt, based on texts and toponyms, assumes that the transition occurred via the intermediate sound γ (as in Belarusian) and that this sound γ already existed in Upper Sorbian in the 12th to 14th centuries. Later, h was mostly lost in Upper Sorbian, except before vowels and after consonants. In most dialects and in Upper Sorbian colloquial language, h also disappeared in intervocalic position. The first written evidence of this dates back to the beginning of the 17th century.

As mentioned, in the 13th century the soft dentals ť and ď in Sorbian became the affricates ć and dź: tělo > ćěło (“body”), devęt > dźewjeć (“nine”). In Upper Sorbian, ć later merged with č, and dź with the allophone č – dž, which led to their phonologization. The Proto-Slavic combinations šč and ždž were first simplified to šť and žď respectively, and then by affrication of ť and ď to šć and ždź. Soft cʼ, zʼ, and sʼ were hardened, and the following i and ě changed to y: Proto-Slavic cělъ > cyły, Proto-Slavic sila > syła, Proto-Slavic zima > zyma. After p, t, k, the sounds r and rʼ in Sorbian changed to ř and řʼ; in Upper Sorbian, this sound later became š. Still later, the combination tš was simplified to cʼ.

The spirant x in Upper Sorbian changed to aspirated k (kʰ) at the beginning of a word before a vowel, and elsewhere to unaspirated k. This change is already evident in texts from the 16th century, though it is not reflected in modern Upper Sorbian orthography. Similar to Polish, hard ł was replaced with w in Upper Sorbian (first evidence from the 17th century), except in the northeastern dialects, while soft lʼ assumed a “European” (alveolar) articulation (like in German), except when followed by a front vowel.

The sound w dropped in Sorbian in the initial clusters gw- and xw-, e.g. Proto-Slavic gvozdj > hózdź (“nail”) and Proto-Slavic hvogsttъ > chróst (“horsetail”), specifically at the beginning of a word before a consonant, and after consonants before u. This process likely began before the 13th century and ended in the 16th century. The soft wʼ in the middle of a word in intervocalic position and before a consonant, as well as at the end of a word, became j: prajić (“to speak”) (Polish: prawić), mužej (“man”) (Polish: mężowi), krej (“blood”) (Polish: krew).

Before soft consonants at the end of a word or elsewhere before other consonants (and before originally soft dental affricates and spirants also in other positions), an epenthetic j appeared in Upper Sorbian. When j follows e or ě, the preceding consonant becomes voiceless. The consonant ń is also hardened before other consonants. This change is not reflected in the spelling: dźeń [ˈd͡ʒejn] (“day”), ležeć [ˈlejʒet͡ʃ] (“to lie”), tež [tejʃ] (“also”), chěža [ˈkʰejʒa] (“house”). This epenthetic j likely already appeared in Upper Sorbian at the end of the 16th century.

The replacement of the dental r by the uvular r in several Upper Sorbian dialects is attributed to German influence.

Remove ads

See also

References

Sources

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads