Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

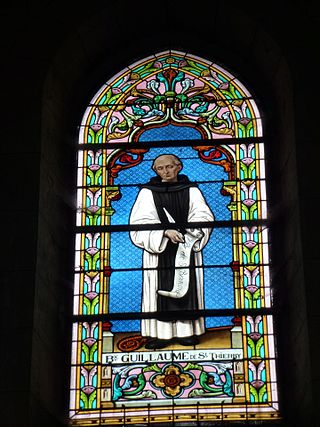

William of Saint-Thierry

Medieval Benedictine and Cistercian theologian From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

William of Saint-Thierry, O. Cist (French: Guillaume de Saint-Thierry; Latin: Guillelmus S. Theodorici; 1075/80/85–1148) was a twelfth-century Benedictine, theologian and mystic from Liège who became abbot of Saint-Thierry in France, and later joined the Cistercian Order.

Biography

Summarize

Perspective

William was born at Liège (in present-day Belgium) of a noble family around 1085 and died at Signy-l'Abbaye in 1148. He probably studied at the cathedral school in Reims, though some have argued it was at Laon, prior to his profession as a Benedictine monk. He became a monk with his brother Simon at the monastery of St. Nicaise in Reims in 1113. From here both eventually became abbots of other Benedictine abbeys: Simon at the abbey of Saint-Nicolas-au-Bois, in the Diocese of Laon, and William at Saint-Thierry, on a hill overlooking Reims, in 1119.[1]

In the years 1116-1118 William met St. Bernard, abbot of the Cistercian monastery of Clairvaux, where they formed an intimate friendship that lasted for life. His greatest desire was to move to Clairvaux and take vows as a Cistercian monk, but Bernard disapproved of the plan and imposed on him the responsibility of remaining abbot at the Benedictine abbey of St. Thierry.[1]

William was instrumental in the first General Chapter meeting of the Benedictine abbots in the Diocese of Reims, in 1131, and it is possible that he hosted the chapter meeting at Saint-Thierry. After the second General Chapter of the Benedictines, held at Soissons in 1132, where many Cistercian reforms were adopted by the Black Monks, William submitted his Responsio abbatum ("Response of the Abbots") to Cardinal Matthew – papal legate in the diocese and critic of the abbots' reforms – successfully defending their efforts at reform. On account of long infirmities and a lifelong desire for a life of contemplation, William resigned his abbacy in 1135 and entered the newly established Cistercian Signy Abbey, also in the diocese of Reims.

According to a contemporary, William died in 1148, about the time of the council held at Reims under Pope Eugenius. The necrology of Signy dates it 8 September, a few years prior to his good friend Bernard's death in 1153.[1]

Remove ads

Writings

Summarize

Perspective

William wrote throughout all of his abbatial career and in his final years as a Cistercian monk. His earliest works reflect a monk seeking God continually and investigating the ways of furthering the soul's ascent to God in spiritual union.

Toward the end of his career, having written extensively on spiritual life and especially on the moral interpretation of the biblical Song of Songs, William came across the writings of Peter Abelard, whose Trinitarian theology and Christology William found to be in error. He wrote his own work against Abelard and alerted others about these concerns, urging St. Bernard to act. As a result, Abelard was condemned by the Council of Sens in 1140 or 1141. William wrote against what he saw as errors in the writings of William of Conches concerning Trinitarian theology and also against Rupert of Deutz on sacramental theology.

Besides his letters to St. Bernard and others, William wrote several works. In total, there were 22 works by William (21 extant), all written in Latin between c. 1121 and 1148.

In approximate chronological order, these include:

- De contemplando Deo (On Contemplating God) in 1121–1124. This is sometimes paired with De natura et dignitate amoris (below) under the title Liber solioquiorum sancti Bernardi.[2]

- De natura et dignitate amoris (On the Nature and Dignity of Love) around the same time. This is sometimes called the Liber beati Bernardi de amore.[3]

- Oratio domni Willelmi (Prayer of William) in 1120s.

- Epistola ad Domnum Rupertum (Letter to Rupert of Deutz).

- De sacramento altaris (On the Sacrament of the Altar) which is the earliest Cistercian text on sacramental theology and written in 1122–23.[4]

- Prologus ad Domnum Bernardum abbatem Claravallis (Preface to Sac Alt to Bernard).

- Brevis commentatio in Canticum canticorum (Brief Comments on the Song of Songs) his first exposition of this biblical text in mid-1120s, written shortly after his time of convalescence with Bernard at Clairvaux.[5]

- Commentarius in Canticum canticorum e scriptis S. Ambrosii (Commentary on the Song of Songs from the Writings of St. Ambrose) around 1128.

- Excerpta ex libris sancti Gregorii super Canticum canticorum (Excerpts from the Books of St. Gregory [the Great] over the Song of Songs) around the same year.

- Responsio abbatum (Response of the Abbots) from the General Chapter of Benedictine abbots in the diocese of Reims in 1132.

- Meditativae orationes (Meditations on Prayer), written c1128-35.[6][7]

- Expositio super Epistolam ad Romanos (Exposition of the Letter to the Romans), written c. 1137.[8]

- De natura corporis et animae (On the Nature of the Body and the Soul), written c. 1138.[9]

- Expositio super Canticum canticorum (Exposition on the Song of Songs) his longer commentary on the Song of Songs, written c1138.[10]

- Disputatio adversus Petrum Abelardum (Disputation against Peter Abelard) as a letter to Bernard in 1139.

- Epistola ad Gaufridum Carnotensem episcopum et Bernardum abbatem Clarae-vallensem (preface to Disputatio).

- Epistola de erroribus Guillelmi de Conchis (Letter on the Errors of William of Conches) also addressed to Bernard in 1141.

- Sententiae de fide (Thoughts on Faith) in 1142 (now lost).

- Speculum fidei (Mirror of Faith) around 1142–1144.[11]

- Aenigma fidei (Enigma of Faith), written c1142-44.[12]

- Epistola ad fratres de Monte-Dei (Letter to the Brothers of Mont-Dieu, more often called The Golden Epistle) in 1144–1145.[13]

- Vita prima Bernardi (First Life of Bernard) in 1147 which was later expanded by other authors after Bernard's death in 1153.

Three of William's writings were widely read in the later Middle Ages. However, they were frequently attributed to Bernard of Clairvaux – a sign of their quality and also another reason for their continued popularity.[14] Only in the early twentieth century did interest in William as a distinct writer begin to develop again and was his name correctly attached to all of his own writings.[15]

William drew upon the existing and traditional monastic and theological authors of his day and significant authors of previous centuries, but not in a slavish way; he is creative and independent in his thought and exposition. His own commentaries show his remarkable insight while they also incorporate traditional authors such as Augustine of Hippo and Origen of Alexandria. Perhaps his most influential works are those dealing with the spiritual life of the contemplative monk. From his On Contemplating God to his Golden Epistle, one can notice an improved, more polished writing style and organization. Some scholars also argue that although William drew on texts and authors in the past, his creativity and usage of spiritual terminology was also influential on many other authors from the 12th century onward.[15]

William's writings are contained in J.-P. Migne's Patrologia Cursus Completus Series Latina (Patrologia Latina) volume 180, with other works in volumes 184 and 185. All of his works are available in critical editions in the Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Medievalis series from Brepols in six volumes (86-89B). The bulk of William's writings are available in English translation from Cistercian Publications.

Remove ads

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads