胆管癌

疾病 / 维基百科,自由的 encyclopedia

胆管癌(Cholangiocarcinoma),又称胆道癌,是一种由胆道上皮细胞(或呈现上皮细胞分化特征的细胞)癌变所造成的癌症[6]。胆管癌主要的症状为肝功能异常、腹痛、黄疸、全身搔痒、发热和体重减轻[1];此外患者的粪便颜色可能变浅,尿液颜色变深[3]。同属胆道系统(英语:biliary tract)癌症的疾病还包括胆囊癌和十二指肠乳头癌(英语:ampulla of Vater)[7]。胆管癌是一种罕见的腺癌[2]。

| 胆管癌 | |

|---|---|

| |

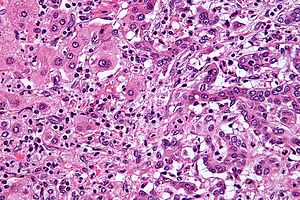

| 肝内胆管癌(右侧)和正常肝细胞(左侧)的组织切片,HE染色。 | |

| 症状 | 腹痛、黄疸、体重下降、全身搔痒、发热[1] |

| 常见始发于 | 约70岁[2] |

| 类型 | 肝内型(Intrahepatic)、肝门型(perihilar)、远端型(distal)[2] |

| 风险因子 | 原发性硬化性胆管炎、溃疡性结肠炎、特定肝吸虫(英语:liver fluke)感染、先天肝发育异常[1] |

| 诊断方法 | 显微病理切片[3] |

| 治疗 | 手术切除(英语:Surgical resection)、化学疗法、放射线疗法、胆道支架、肝脏移植(英语:liver transplantation)[1] |

| 预后 | 通常很差[4] |

| 盛行率 | 约每年每10万人1–2例(西方国家)[5] |

| 分类和外部资源 | |

| 医学专科 | 肿瘤学 |

| ICD-11 | XH7M15 |

| OMIM | 615619 |

| DiseasesDB | 2505 |

| MedlinePlus | 000291 |

| eMedicine | 277393、365065 |

| [编辑此条目的维基数据] | |

胆管癌的风险因子包含原发性硬化性胆管炎、溃疡性结肠炎、肝硬化、丙型肝炎、乙型肝炎、特定肝吸虫(英语:liver fluke)感染,以及先天肝脏结构异常等等[1][2][8]。但大多数胆管癌患者缺乏明确的风险因子背景可供辨识[2]。疾病的诊断须结合血液检查、医学影像,和内窥镜检查,有时需手术取出检体进行病理诊断。确诊须经由显微镜检进行[3]。

多数患者在诊断出胆管癌时,疾病已经进展至晚期,无法治愈。在这些无法治愈的病人可进行和缓医疗,包含手术切除(英语:surgical resection)、化学疗法、放射线疗法,以及置放胆道支架等等。完全手术切除是唯一的治愈希望,但有约三分之一的病人肿瘤会进犯总胆管(英语:common bile duct),而此类肿瘤无法手术切除,因此仅有少数肿瘤可以进行完全切除。完全切除后仍然建议继续进行化疗及放疗[1]。有些符合特定条件的病人可以进行肝脏移植(英语:liver transplantation)[2],但术后的五年存活率仍不到五成[5]。

胆管癌在西方世界相当罕见,大约每年每10万人仅 0.5–2 例[1][5]。东南亚等肝吸虫流行的地区发生率较高,如泰国约每年每10万人60例[4]。韩国、上海的发生率甚至高于罕见癌症的标准[9]。胆管癌一般发生于70岁左右,但患有原发性硬化性胆管炎者常在40岁左右即发病[2]。现今西方国家的肝内型胆管癌比例比起过去较高[5]。