Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Javanese language

Austronesian language From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Javanese (/ˌdʒɑːvəˈniːz/ JAH-və-NEEZ,[3] /dʒævə-/ JAV-ə-, /-ˈniːs/ -NEESS;[4] Basa Jawa, Javanese script: ꦧꦱꦗꦮ, Pegon: باسا جاوا, IPA: [bɔsɔ d͡ʒɔwɔ]) is an Austronesian language spoken primarily by the Javanese people from the central and eastern parts of the island of Java, Indonesia. There are also pockets of Javanese speakers on the northern coast of western Java. It is the native language of more than 68 million people.[5]

Javanese is the largest of the Austronesian languages in number of native speakers. It has several regional dialects and a number of clearly distinct status styles.[6] Its closest relatives are the neighboring languages such as Sundanese, Madurese, and Balinese. Most speakers of Javanese also speak Indonesian for official and commercial purposes as well as a means to communicate with non-Javanese-speaking Indonesians.

There are speakers of Javanese in Malaysia (concentrated in the West Coast part of the states of Selangor and Johor) and Singapore. Javanese is also spoken by traditional immigrant communities of Javanese descent in Suriname, Sri Lanka and New Caledonia.[7]

Along with Indonesian, Javanese is an official language in the Special Region of Yogyakarta, Indonesia.[2]

Remove ads

Geographical distribution

Summarize

Perspective

Javanese is spoken throughout Indonesia, neighboring Southeast Asian countries, the Netherlands, Suriname, New Caledonia, and other countries. The largest populations of speakers are found in the six provinces of Java itself, and in the neighboring Sumatran province of Lampung.

The language is spoken in Yogyakarta, Central and East Java, as well as on the north coast of West Java and Banten. It is also spoken elsewhere by the Javanese people in other provinces of Indonesia, who are numerous due to the government-sanctioned transmigration program in the late 20th century, including Lampung, Jambi, and North Sumatra provinces. In Suriname, Javanese is spoken among descendants of plantation migrants brought by the Dutch during the 19th century.[8] In Madura, Bali, Lombok, and the Sunda region of West Java, it is also used as a literary language. It was the court language in Palembang, South Sumatra, until the palace was sacked by the Dutch in the late 18th century.

Javanese is written with the Latin script, Javanese script, and Arabic script.[9] In the present day, the Latin script dominates writings, although the Javanese script is still taught as part of the compulsory Javanese language subject in elementary up to high school levels in Yogyakarta, Central and East Java.

Javanese is the twenty-second largest language by native speakers and the seventh largest language without official status at the national level. It is spoken or understood by approximately 100 million people. At least 45% of the total population of Indonesia are of Javanese descent or live in an area where Javanese is the dominant language. All seven Indonesian presidents since 1945 have been of Javanese descent.[a] It is therefore not surprising that Javanese has had a deep influence on the development of Indonesian, the national language of Indonesia.

There are three main dialects of the modern language: Central Javanese, Eastern Javanese, and Western Javanese. These three dialects form a dialect continuum from northern Banten in the extreme west of Java to Banyuwangi Regency in the eastern corner of the island. All Javanese dialects are more or less mutually intelligible.

A table showing the number of native speakers in 1980, for the 22 Indonesian provinces (from the total of 27) in which more than 1% of the population spoke Javanese:[b]

According to the 1980 census, Javanese was used daily in approximately 43% of Indonesian households. By this reckoning there were well over 60 million Javanese speakers,[10] from a national population of 147,490,298.[11][d]

In Banten, the descendants of the Central Javanese conquerors who founded the Islamic Sultanate there in the 16th century still speak an archaic form of Javanese.[12] The rest of the population mainly speaks Sundanese and Indonesian, since this province borders directly on Jakarta.[e]

At least one third of the population of Jakarta are of Javanese descent, so they speak Javanese or have knowledge of it. In the province of West Java, many people speak Javanese, especially those living in the areas bordering Central Java, the cultural homeland of the Javanese.

Almost a quarter of the population of East Java province are Madurese (mostly on the Isle of Madura); many Madurese have some knowledge of colloquial Javanese. Since the 19th century, Madurese was also written in the Javanese script.[f]

The original inhabitants of Lampung, the Lampungese, make up only 15% of the provincial population. The rest are the so-called "transmigrants", settlers from other parts of Indonesia, many as a result of past government transmigration programs. Most of these transmigrants are Javanese who have settled there since the 19th century.

In Suriname (the former Dutch colony of Surinam), South America, approximately 15% of the population of some 500,000 are of Javanese descent, among whom 75,000 speak Javanese. A local variant evolved: the Tyoro Jowo-Suriname or Suriname Javanese.[13]

Remove ads

Classification

Summarize

Perspective

Javanese is part of the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family, although its precise relationship to other Malayo-Polynesian languages is hard to determine. Using the lexicostatistical method, Isidore Dyen classified Javanese as part of the "Javo-Sumatra Hesion", which also includes the Sundanese and "Malayic" languages.[g][14][15] This grouping is also called "Malayo-Javanic" by linguist Berndt Nothofer, who was the first to attempt a reconstruction of it based on only four languages with the best attestation at the time (Javanese, Sundanese, Madurese, and Malay).[16]

Malayo-Javanic has been criticized and rejected by various linguists.[17][18] Alexander Adelaar does not include Javanese in his proposed Malayo-Sumbawan grouping (which also covers Malayic, Sundanese, and Madurese languages).[18][19] Robert Blust also does not include Javanese in the Greater North Borneo subgroup, which he proposes as an alternative to Malayo-Sumbawan grouping. However, Blust also expresses the possibility that Greater North Borneo languages are closely related to many other western Indonesian languages, including Javanese.[20] Blust's suggestion has been further elaborated by Alexander Smith, who includes Javanese in the Western Indonesian grouping (which also includes GNB and several other subgroups), which Smith considers as one of Malayo-Polynesian's primary branches.[21]

Remove ads

Dialects

Summarize

Perspective

There are three main groups of Javanese dialects, based on sub-regions: Western Javanese, Central Javanese, and Eastern Javanese. The differences are primarily in pronunciation, but with vocabulary differences also. Not all Javanese dialects are mutually intelligible; for example, a Javanese speaker from Surabaya might not be able to understand the Javanese spoken in Tegal, or the formal registers spoken in parts of Central Java.

A preliminary general classification of Javanese dialects given by the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology's Department of Linguistics is as follows.[22] Pesisir (Tegalan), Banyumas and Tengger are considered to be among the most conservative dialects.[23][24] The Banten, Pesisir Lor, Banyumas and Tengger dialect do not have the vowel raising and vowel harmony features that are innovations of the "standard" Solo and Yogyakarta dialects.

- West Java (Geographically) :

- Central Java (Geographically) :

- East Java (Geographically)

Dialects description

Standard Javanese

Standard Javanese is the variety of the Javanese language that was developed at the Yogyakarta and Surakarta courts (the heirs to the Mataram Sultanate that once dominated the whole of Java and beyond), based on the Central Javanese dialect, and becomes the basis for the Javanese modern writings. It is marked with the strict usage of two speech levels for politeness, i.e. vernacular level called ngoko and high-register level called krama. Other dialects do not contrast the usage of the speech levels.[28]

Central Javanese

Central Javanese (Jawa Tengahan) is founded on the speech of Surakarta[h] and to a lesser extent of Yogyakarta. It is considered the most "refined" of the regional variants, and serves as a model for the standard language. This variant is used throughout eastern part of Central Java, the Special Region of Yogyakarta, and the western and southern part of East Java provinces. There are many lower-level dialects such as Kedu (influenced by Banyumasan), Muria and Semarangan, as well as Surakarta and Yogyakarta themselves. Javanese spoken in the Western and Southern Part of East Java (Madiun, Ponorogo, Ngawi, Magetan, Pacitan, Tulungagung, Trenggalek and most parts of Kediri, Nganjuk and Blitar) bears a strong influence of Surakarta Javanese.

This variant is also used by Mataraman descendant's outside the Mataraman cultural area, like small part of western region of Jombang Regency, small part of western region of Malang Regency, almost of southern part of Banyuwangi Regency (pesanggaran until tegaldlimo district) and south and southeastern part of Jember Regency (Wuluhan until Tempurejo district). The variation of Central Javanese are said to be so plentiful that almost every administrative region (or kabupatèn) has its own local slang.

There some influences of other dialect, like in the eastern part of Nganjuk (greater Kertosono), north and northeastern part of Kediri (ex kawedanan Papar & ex kawedanan Pare) and the eastern part of Blitar (ex kawedanan Wlingi) there is some influences of the Arekan dialect, even though the basic vocabulary is still predominantly Mataraman and still classified as Mataraman Dialect.

- Mataram dialect, Kewu dialect, or Standard dialect is spoken commonly in Yogyakarta, Surakarta, Klaten, Karanganyar, Wonogiri, Sukoharjo, Sragen, Boyolali, and eastern half of Magelang Regency.

- Pekalongan dialect is spoken in Pekalongan, Pekalongan regency, Batang and also in Pemalang.

- Kedu dialect is spoken in the former Kedu residency, including: Temanggung, eastern part of Kebumen, Magelang, and Wonosobo.

- Bagelen dialect is sub-dialect of Kedu spoken in Purworejo.

- Semarang dialect is spoken in Semarang, Semarang regency, and also Salatiga, Grobogan, Demak and Kendal.

- Muria (Agung) dialect or Eastern North-Coast dialect is spoken in Jepara, Rembang, Kudus, Pati, and also in Tuban and Bojonegoro.

- Madiunan dialect or Mataraman dialect is spoken mainly in western part of East Java province, including Madiun, Ngawi, Pacitan, Ponorogo, Magetan, Kediri, Nganjuk, Trenggalek, Tulungagung, and Blitar.

Western Javanese

Western Javanese (Jawa Kulonan), spoken in the western part of the Central Java province and throughout the West Java and Banten province (particularly on the north coast), includes dialects that are distinct for their Sundanese influences. It retains many archaic words and original pronunciation from Old Javanese.

- North Banten dialect (Jawa Sérang) is spoken in Serang, Cilegon, and the western part of Tangerang regency.

- Cirebon dialect (Cirebonan or basa Cerbon) is spoken in Cirebon, Indramayu, and Losari.

- Tegal dialect, known as Tegalan or dhialèk Pantura (North-Coast dialect), is spoken in Tegal, Brebes, and the western part of Pemalang regency.

- Banyumas dialect, known as Banyumasan, is spoken in Banyumas, Cilacap, Purbalingga, Banjarnegara, and Bumiayu.

Some Western Javanese dialects such as Banyumasan dialects and Tegal dialect are sometimes referred to as basa ngapak by other Javanese because of the dialectal pronunciation of word apa (what).

Eastern Javanese

Eastern Javanese (Jawa Wétanan) speakers range from the eastern banks of Brantas River in Kertosono, and from Jombang to Banyuwangi, comprising the second majority of the East Java province excluding Madura island, Situbondo and Bondowoso. However, some variant like Pedalungan has been influenced by Madurese.

The most outlying Eastern Javanese dialect is spoken in Balambangan (or Banyuwangi). It is generally known as basa Using. Using, a local negation word, is a cognate of tusing in Balinese.

- Arekan dialect is commonly spoken in Surabaya, Malang, Gresik, Mojokerto, Pasuruan, Lumajang, western and south-western part of Jember, eastern part of Lamongan, and Sidoarjo. Many Madurese people also use this dialect as their second language.

- Pasisir Lor Wétan (Northeastern Coast) or Surabaya dialect is spoken in Surabaya, Sidoarjo, southern part of Gresik, Mojokerto and most part of Lamongan.

- Malang-Pasuruhan dialect is spoken in Malang and Pasuruan.

- Lumajangan dialect is sub-dialect of arekan, bit influenced by madurese languages, spoken in west and southern part of Lumajang (except in north and north-east which base of madurese people's) and also spoken in southwestern part of Jember like Kencong, Jombang, Umbulsari, Gumukmas and southern part of Sumberbaru.

- Jombang dialect is sub dialect of Arekan, bit influenced by Mataraman Javanese dialect, spoken in most part of Jombang

- Gresik dialect or Giri dialect is the outermost in the Arekan dialect group spoken in the northern and central regions of Gresik Regency. Gresik Javanese is thought to be a blend of Arekan Javanese (especially the Surabaya dialect) with Javanese from the Kesunanan Giri era.

- Tengger dialect used by Tengger people, which is centered in thirty villages in the isolated Tengger mountains (Mount Bromo) within the Bromo Tengger Semeru National Park in East-Central Java.

- Osing dialect or Blambangan dialect is spoken in central part of Banyuwangi.

Surinamese-Javanese

Surinamese-Javanese is mainly based on Central Javanese, especially from Kedu Residency. The number of speakers of Suriname-Javanese in Suriname was estimated at 60,000 as of 2012.[29] Most Surinamese-Javanese are bi- or trilingual. According to the 2004 census, Surinamese-Javanese was the first or second language in 11 percent of households. In a 2012 study of multilingualism in Surinamese education by the Dutch Language Union,[29] 3,497 out of 22,643 pupils (15 percent) in primary education indicated Surinamese-Javanese as a language spoken at home. Most of them were living in Wanica and Paramaribo districts.

Not all immigrants from Indonesia to Suriname were speakers of Javanese. Immigration records show that 90 percent of immigrants were Javanese, with 5 percent Sundanese, 0.5 percent Madurese and 2.5 percent from Batavia. The ethnic composition of this last group was not determinable. Probably Sundanese, Madurese or Malay speaking immigrants were forced to learn Javanese during their stay in Suriname to adapt. In view of the language policies in Netherlands Indies at the time of immigration, it is unlikely the immigrants had knowledge of the Dutch language prior to immigration to Suriname. Dutch today is the official language of Suriname.

Surinamese Javanese is somewhat different from Indonesian Javanese.[30][31] In Surinamese-Javanese there is a difference between formal and informal speech. Surinamese-Javanese took many loanwords from languages like Dutch, Sranantongo, Sarnami and Indonesian. The influence of the latter language, which is not spoken in Suriname, can be attributed to the Indonesian embassy and Islamic teachers from Indonesia. Indonesian movies are popular, and usually shown without subtitles on Surinamese-Javanese television channels.

In 1986, the Surinamese government adopted an official spelling for Surinamese-Javanese.[32] It is seldom used as a written language, however.

In the 2012 survey, pupils who indicated Surinamese-Javanese as a language spoken at home, reported Dutch (97.9 percent) and Sranantongo (76.9 percent) also being spoken in the household.

Surinamese-Javanese speaking pupils report high proficiency in speaking and understanding, but very low literacy in the language. They report a low preference for the language in interaction with family members, including their parents, with the exception of their grandparents. Pupils where Surinamese-Javanese is spoken at home tend to speak Dutch (77 percent) rather than Surinamese-Javanese (12 percent).

New Caledonian Javanese

As expected, New Caledonian Javanese is somewhat different from Indonesian Javanese. New Caledonian Javanese took many loanwords from French. New Caledonian society, in addition to their mastery of the language according to their ethnicity (Javanese New Caledonians), is obliged to be fluent in French that is a medium that is used in all the affairs of the state, economy, and education. French is regarded as a prestigious language because it is the language of the government, an official language in France include New Caledonia, one of the major languages in Europe, and one of the official languages of the United Nations.[33]

Phonetic differences

Phoneme /i/ at closed ultima is pronounced as [ɪ] in Central Javanese (Surakarta–Yogyakarta dialect), as [i] in Western Javanese (Banyumasan dialect), and as [ɛ] in Eastern Javanese.

Phoneme /u/ at closed ultima is pronounced as [ʊ] in Central Javanese, as [u] in Western Javanese, and as [ɔ] in Eastern Javanese.

Phoneme /a/ at closed ultima in Central Javanese is pronounced as [a] and at open ultima as [ɔ]. Regardless of position, it tends toward [a] in Western Javanese and as [ɔ] in Eastern Javanese.

Western Javanese tends to add a glottal stop at the end of word-final vowels, e.g.: Ana apa? [anaʔ apaʔ] "What happened?", Aja kaya kuwè! [adʒaʔ kajaʔ kuwɛʔ] "Don't be like that!".

Final consonant devoicing occurs in the standard Central Javanese dialect, but not in Banyumasan. For example, endhog (egg) is pronounced [əɳɖ̥ɔk] in standard Central Javanese, but [əɳɖ̥ɔg] in Banyumasan. The latter is closer to Old Javanese.[25]

Vocabulary differences

The vocabulary of standard Javanese is enriched by dialectal words. For example, to get the meaning of "you", Western Javanese speakers say rika /rikaʔ/, Eastern Javanese use kon /kɔn/ or koen /kɔən/, and Central Javanese speakers say kowé /kowe/. Another example is the expression of "how": the Tegal dialect of Western Javanese uses keprimèn /kəprimen/, the Banyumasan dialect of Western Javanese employs kepriwé /kəpriwe/ or kepribèn /kəpriben/, Eastern Javanese speakers say ya' apa /jɔʔ ɔpɔ/ – originally meaning "like what" (kaya apa in standard Javanese) or kepiyé /kəpije/ – and Central Javanese speakers say piye /pije/ or kepriyé /kəprije/.

The Madiun–Kediri dialect has some idiosyncratic vocabulary, such as panggah 'still' (standard Javanese: pancet), lagèk 'progressive modal' (standard Javanese: lagi), and emphatic particles nda, pèh, and lé.[26]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

In general, the history of the Javanese language can be divided into two distinct phases: 1) Old Javanese and 2) New Javanese.[19][34]

Old Javanese

The earliest attested form of Old Javanese can be found on the Sukabumi inscription at Kediri regency, East Java which dates from 804 CE.[35] Between the 8th and the 15th century, this form of Javanese flourished in the island of Java. Old Javanese is commonly written in the form of verses. This language variety is also called kawi or 'of poets, poetical's, although this term could also be used to refer to the archaic elements of New Javanese literature.[19] The writing system used to write Old Javanese is a descendant of the Pallava script from India.[35] Almost half of the entire vocabularies found in Old Javanese literature are Sanskrit loanwords, although Old Javanese also borrowed terms from other languages in the Maritime Southeast Asia.[19][35]

The form of Old Javanese found in several texts from 14th century onward (mostly written in Bali) is sometimes referred to as "Middle Javanese". Both Old and Middle Javanese written forms have not been widely used in Java since early 16th century. However, Old Javanese works and poetic tradition continue to be preserved in the Javanese-influenced Bali, and the variety is also used for religious purposes.[19][36]

Modern Javanese

Modern Javanese emerged as the main literary form of the language in the 16th century. The change in the literary system happened as Islam started to gain influence in Java.[34] In its early form, Modern Javanese literary form was based on the variety spoken in the north coast of Java, where Islam had already gained foothold among the local people. Many of the written works in this variety were Islamic in nature, and several of them were translation from works in Malay.[37] The Arabic abjad was also adopted (as Pegon) to write Javanese.[34][37]

The rise of Mataram in the 17th century shifted the main literary form of Javanese to be based on the inland variety. This written tradition was preserved by writers of Surakarta and Yogyakarta, and later became the basis of the modern written standard of the language.[37] Another linguistic development associated with the rise of Mataram is the stratification of Javanese into speech levels such as ngoko and krama,[38] which were unknown in Old Javanese.[37][38]

Books in Javanese have been printed since 1830s, at first using the Javanese script, although the Latin alphabet started to be used later. Since mid-19th century, Javanese has been used in newspapers and travelogues, and later, also novels, short stories, as well as free verses. Today, it is used in media, ranging from books to TV programs, and the language is also taught at schools in primarily Javanese areas.

Although Javanese is not a national language, it has recognized status as a regional language in the three Indonesian provinces with the biggest concentrations of Javanese people: Central Java, Yogyakarta, and East Java.[citation needed] Javanese is designated as the official language of the Special Region of Yogyakarta under Yogyakarta Special Region Regulation Number 2 of 2021.[2] Previously, Central Java promulgated a similar regulation—Regional Regulation 9/2012[39]—but this did not imply an official status for the language.

Javanese is taught at schools and is used in some mass media, both electronically and in print. There is, however, no longer a daily newspaper in Javanese. Javanese-language magazines include Panjebar Semangat, Jaka Lodhang, Jaya Baya, Damar Jati, and Mekar Sari. Damar Jati, a new Javanese language magazine, appeared in 2005 is not published in the Javanese heartlands, but in Jakarta.

Since 2003, an East Java local television station (JTV) has broadcast some of its programmes in the Surabayan (Suroboyoan) dialect, including Pojok Kampung ("Village Corner", main newscast), Kuis RT/RW ("RT/RW Quiz"), and Pojok Perkoro ("Case Corner", a crime newscast). In later broadcasts, JTV offers programmes in the Central Javanese dialect (called by them basa kulonan, "the western language") and Madurese. The speakers of Suroboyoan dialect are well known for being proud of their distinctive dialect and consistently maintain it wherever they go.[40]

Remove ads

Endangerment

Several linguists has voiced concerns about the status of Javanese. It is believed that Ngoko Javanese enjoys a stable diglossic status, while Krama Javanese is under more serious threat.[41] The number of Javanese native speakers has significantly dwindled over the years. In a research in Yogyakarta, it was revealed that a significant number of parents do not transmit Javanese to their children.[42] Instead, Javanese speakers typically acquire Javanese through extrafamilial sources, like friend groups.[43] Although Javanese enjoys a large quantity of speaker base, it is not immune from pressures from other languages like Indonesian and English.[41]

Remove ads

Phonology

Summarize

Perspective

The Javanese language has 23–25 consonant phonemes and 6–8 vowel phonemes.[44][45][46] The dialects of Javanese each have their own distinct characteristics in terms of phonology.[44]

The phonemes of Modern Standard Javanese as shown below.[47][48]

Vowels

There is disagreement regarding the number of vowel phonemes in Javanese. According to the Javanese linguist E. M. Uhlenbeck, Javanese has six vowel phonemes, each of which has two pronunciation variants (allophones), except for the schwa /ə/.[49] This view is supported by several other Javanese linguists. However, an alternative analysis by some linguists concludes that Javanese has two additional phonemes, namely /ɛ/ and /ɔ/, which are considered independent phonemes, separate from /e/ and /o/.[45][46]

Following the six-vowel analysis, the phonemes above have the following allophones:

- The phoneme /i/ has two allophones: [i], which generally appears in open syllables, and [ɪ], in closed syllables.[44]

- mari [mari] ‘to recover’

- wit [wɪt] ‘seedling’

- The phoneme /u/ has two allophones: [u], which generally appears in open syllables, and [ʊ], in closed syllables.[44]

- kuru [kuru] ‘thin’

- mung [mʊŋ] ‘only’

- The phoneme /e/ has two allophones: [e] and [ɛ], which can appear in both open and closed syllables.[44] In open syllables, /e/ is realized as [ɛ] if that syllable is followed by (1) an open syllable with the vowel [i] or [u], (2) a syllable with an identical vowel, or (3) a syllable containing the vowel [ə].[50]

- saté [sate] ‘satay’

- mèri [mɛri] ‘jealous’

- kalèn [kalɛn] ‘drain, gutter’

- The phoneme /o/ has two allophones: [o], which generally appears in open syllables, and [ɔ], which can appear in both open and closed syllables.[44] In open syllables, /o/ is realized as [ɔ] if that syllable is followed by (1) an open syllable with the vowel [i] or [u], (2) a syllable with an identical vowel, or (3) a syllable containing the vowel [ə].[50]

- loro [loro] ‘two’

- kori [kɔri] ‘gate’

- sorot [sorɔt] ‘ray, light’

- The phoneme /a/ has two allophones: [a], which generally appears in penultimate (second-to-last) and antepenultimate (third-to-last) syllables, whether open or closed; and [ɔ], which can appear in open syllables.[44] In open syllables, /a/ is only realized as [ɔ] if the syllable occurs at the end of a word, or if it is the penultimate syllable of a word ending in /a/.[50]

- bali [bʰali] ‘to go home’

- kaloka [kalokɔ] ‘famous’

- kaya [kɔyɔ] ‘like, as if’

- The phoneme /ə/ is always pronounced as [ə].[44]

- metu [mətu] ‘to go out’

- pelem [pələm] ‘mango’

In closed syllables the vowels /i u e o/ are pronounced [ɪ ʊ ɛ ɔ] respectively.[47][51] In open syllables, /e o/ are also [ɛ ɔ] when the following vowel is /i u/ in an open syllable; otherwise they are /ə/, or identical (/e...e/, /o...o/). In the standard dialect of Surakarta, /a/ is pronounced [ɔ] in word-final open syllables, and in any open penultimate syllable before such an [ɔ]. Example: Janaka = /dʒ̊anɔkɔ/ and Nakula = /nakulɔ/.

Consonants

The Javanese "voiced" phonemes are not in fact voiced but voiceless, with breathy voice on the following vowel.[47] The relevant distinction in phonation of the plosives is described as stiff voice versus slack voice.[52][48]

A Javanese syllable can have the following form: CSVC, where C = consonant, S = sonorant (/j/, /r/, /l/, /w/, or any nasal consonant), and V = vowel. As with other Austronesian languages, native Javanese roots consist of two syllables; words consisting of more than three syllables are broken up into groups of disyllabic words for pronunciation. In Modern Javanese, a disyllabic root is of the following type: nCsvVnCsvVC.

Apart from Madurese, Javanese is the only language of Western Indonesia to possess a distinction between dental and retroflex phonemes.[47] The latter sounds are transcribed as "th" and "dh" in the modern Roman script, but previously by the use of an underdot: "ṭ" and "ḍ".

Phonotactics

The most common syllable structures in Javanese are V, CV, VC, and CVC. Syllables may also begin with consonant clusters, which are generally divided into three types: 1) homorganic consonant clusters consisting of a nasal sound plus a voiced stop (NCV, NCVC), 2) consonant clusters consisting of a stop plus a liquid or semivowel (CCV, CCVC), and 3) homorganic nasal consonant clusters followed by a liquid and semivowel (NCCV, NCCVC).

| V | : ka-é 'that' | |

| CV | : gu-la 'sugar' | |

| VC | : pa-it 'bitter' | |

| CVC | : ku-lon 'west' | |

| CCV (including NCV) | : bla-bag 'board', kre-teg 'bridge' | |

| CCVC (including NCVC) | : prap-ta 'arrive' | |

| NCCVC | : ngglam-byar 'unfocused' |

Consonant clusters between vowels generally consist of a nasal + homorganic stop (such as [mp], [mb], [ɲtʃ], and so on), or [ŋs]. The sounds /l/, /r/, and /j/ can also be added at the end of such consonant clusters. Examples of such consonant clusters are wonten ‘exist’, bangsa ‘nation’, and santri ‘santri, devout Muslim’. In Javanese, the syllable before such consonant clusters is conventionally considered an open syllable, because the sound /a/ in such a syllable undergoes rounding into [ɔ]. The word tampa ‘accept’, for instance, is pronounced [tɔmpɔ]. Compare this with the word tanpa ‘without’, which is pronounced [tanpɔ].

Most morphemes (85%) in Javanese consist of two syllables; the remaining morphemes have one, three, or four syllables. Javanese speakers have a strong tendency to change monosyllabic morphemes into disyllabic morphemes. Morphemes with four syllables are sometimes also analyzed as combinations of two morphemes each with two syllables.

Stress

Views on stress in Javanese differ. Some linguists have claimed that there is (weak) stress on the penultimate syllable of a word, unless that syllable contains a schwa; if it does, the stress is on the final syllable. Another opinion that appears in the literature is that Javanese stress is word-final. In any case, Javanese stress is considered not to be contrastive.[53]

Remove ads

Writing system

Summarize

Perspective

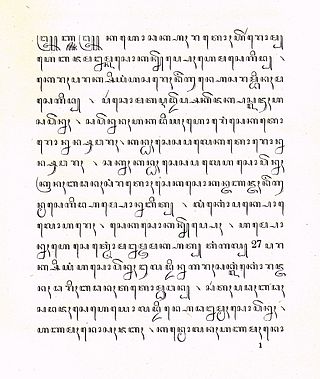

Javanese has been traditionally written with Javanese script. Javanese and the related Balinese script are modern variants of the old Kawi script, a Brahmic script introduced to Java along with Hinduism and Buddhism. Kawi is first attested in a legal document from 804 AD. It was widely used in literature and translations[54] from Sanskrit from the 10th century; by the 17th, the script is identified as carakan.

The Javanese script is an abugida. Each of the twenty letters represents a syllable with a consonant (or a "zero consonant") and the inherent vowel 'a' that is pronounced as /ɔ/ in open position. Various diacritics placed around the letter indicate a different vowel than [ɔ], a final consonant, or a foreign pronunciation.

Letters have subscript forms used to transcribe consonant clusters, though the shapes are relatively straightforward, and not as distinct as conjunct forms of Devanagari. Some letters are only present in old Javanese and became obsolete in modern Javanese. Some of these letters became "capital" forms used in proper names. Punctuation includes a comma; period; a mark that covers the colon, quotations, and indicates numerals; and marks to introduce a chapter, poem, song, or letter.

However, Javanese can also be written with the Arabic script (known as the Pegon script) and today generally uses Latin script instead of Javanese script for practical purposes. A Latin orthography based on Dutch was introduced in 1926, revised in 1972–1973; it has largely supplanted the carakan. The current Latin-based forms:

| Majuscule forms (uppercase) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A | Å | B | C | D | Dh | E | É | È | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | Ng | Ny | O | P | Q | R | S | T | Th | U | V | W | X | Y | Z |

| Minuscule forms (lowercase) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a | å | b | c | d | dh | e | é | è | f | g | h | i | j | k | l | m | n | ng | ny | o | p | q | r | s | t | th | u | v | w | x | y | z |

| IPA | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a | ɔ | b̥ | tʃ | d̪̥ | ɖ̥ | ə, e | e | ɛ | f | ɡ̊ | h | i | dʒ̊ | k | l | m | n | ŋ | ɲ | ɔ, o | p | q | r | s | t̪ | ʈ | u | v | w | x | j | z |

The italic letters are used in loanwords from European languages and Arabic.

Javanese script:

| Base consonant letters | |||||||||||||||||||

| ꦲ | ꦤ | ꦕ | ꦫ | ꦏ | ꦢ | ꦠ | ꦱ | ꦮ | ꦭ | ꦥ | ꦝ | ꦗ | ꦪ | ꦚ | ꦩ | ꦒ | ꦧ | ꦛ | ꦔ |

| ha | na | ca | ra | ka | da | ta | sa | wa | la | pa | dha | ja | ya | nya | ma | ga | ba | tha | nga |

Remove ads

Grammar

Summarize

Perspective

Morphology

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2022) |

Javanese, like many other Austronesian languages, is an agglutinative language, where base words are modified through extensive use of affixes.

Personal pronoun

Javanese has no specific personal pronoun to express plural except for kita which was influenced by Indonesian's first person plural inclusive pronoun. Pronoun pluralization can be ignored or expressed by using phrases such as aku kabèh 'we', awaké dhéwé 'us', dhèwèké kabèh 'them' and so on. Personal pronoun in Javanese, especially for the second and third person, are more often replaced by certain nouns or titles. In addition to the pronoun described in the table below, Javanese still has a variety of other pronoun whose use varies depending on the dialect or level of speech.[44][55][56][page needed]

Personal pronouns in Javanese, especially for the second and third persons, are more often replaced with specific nouns or titles. In addition to the pronouns listed in the table above, Javanese still has a wide variety of other pronouns whose usage varies depending on the dialect or speech level.

Demonstrative

The words iki and iku can be used both in writing and in conversation. The forms kiyi, kiyé, kuwi, and kuwé are mainly used in everyday speech. The form ika is only used in traditional Javanese poetry (tembang).

The madya (middle-level politeness) forms of iki/kiyi/kiyé, iku/kuwi/kuwé, and kaé are niki, niku, and nika. These three types of demonstratives all share the same krama (high-level politeness) form, which is punika or menika, although in some cases the words mekaten or ngaten are also used as polite equivalents of kaé.

Noun

In Javanese, modifiers (attributes) of a head noun are placed after the noun. The head noun does not take affixes if it is followed by an attributive adjective or a non-passive verb (indicating purpose or function) that restricts the meaning of the noun. Possession can be expressed implicitly without affixes, or explicitly with the suffix -(n)é or -(n)ipun on the head noun.

- wit kinah — ‘cinchona tree’

- sumur jero — ‘deep well’

- peranti nenun — ‘weaving tools’

- idham-idhaman kita — ‘our ideals’

- omahé Marsam — ‘Marsam’s house’

The suffix -(n)ing, mainly used in written style, has several distinct meanings that indicate the relationship between the head noun and the attribute.

- ratuning buta — ‘the king of the giants’

- rerengganing griya — ‘decoration for the house’

- dèwining kaéndahan — ‘goddess of beauty’

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2023) |

Numeral

Numerals are generally placed after the noun.[44][50]

- wong siji — ‘one person’

- gelas pitu — ‘seven glasses’

- candhi sèwu — ‘a thousand temples’

Numerals are placed before the noun if the noun refers to a unit of measure or a unit of number. In this position, numerals take a nasal linker: -ng if they end in a vowel, or -ang if they end in a non-nasal consonant. The only exception is the numeral siji ‘one’, which is replaced by the prefixes sa-, se-, or s- in this context.[44][50]

- telu-ng puluh — ‘thirty’

- pat-ang pethi — ‘four chests’

- sa-genthong — ‘one jar’

- se-gelas — ‘a glass (of)’

- s-atus rupiyah — ‘one hundred rupiah’

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2023) |

Verb

The paradigm of standard Javanese verbs can be summarized as follows:

Not all verbal affixes in the paradigm described above are commonly used in everyday conversation. In addition, other Javanese dialects generally have a simpler verb paradigm, such as the Tengger dialect which does not use different affixes for verbs with subjunctive and imperative moods (although the standard dialect also does not distinguish between the two in the active form, both are marked with the affixes N- and -a).

Transitive verbs in Javanese can be formed by attaching the nasal prefix N- to the root word for the active form, or pronominal prefixes such as di-, tak-, and kok- for the passive form.

(1)

Wis

already

nemu

AV:find

akal

solution/idea

aku

I

‘I have already found the solution.'

(2)

Kandha=ku

speech/word=1.GEN

di-gugu

PASS:3-believe

wong

people

akèh

many

‘My words are trusted by many people.’

The addition of the suffixes -i and -aké generally indicates higher valency. The suffix -i is usually applicative, as in tanduri ‘plant with (something)’ from the root tandur ‘to plant’. The suffix -aké (polite/krama form: -aken) can form causative verbs from transitive verbs, e.g. lebokaké ‘put in (into something)’ from mlebu ‘to enter’. When attached to an intransitive verb, the derived verb can be benefactive, e.g. jupukaké ‘take (for someone)’ from the root jupuk ‘take’.

(3)

Kuwi

that

mangan-i

AV:eat-TR

godhong

leaf

tèh

tea

‘That [insect] eats the tea leaves.'

(4)

Para

PL

utusan

envoy

mau

ANAPH

uga

also

ng-islam-aké

AV-Islam-SS

wong-wong

people(plural)

ing

LOC

Pejajaran

Pejajaran

‘These envoys also converted the people in Pejajaran to Islam.’

Both transitive and intransitive verbs have several forms depending on their grammatical mood. In addition to the base or indicative form, there are also the irrealis/subjunctive, imperative, and propositive forms. The irrealis mood in Javanese is expressed with the suffix -a, which can have several meanings:

- Potential (expressing possibility).

(5)

Daya-daya

quickly

tekan-a

arrive-IRR

ing

LOC

omah

house

‘Quickly, [he/she] might arrive at home.’

- Conditional (expressing supposition)

(6)

Aja-a

NEG.IMP-IRR

ana

EXIST

lawa,

bat,

lemud

mosquito

kuwi

that

rak

PTCL

ndadi

become

‘If there were no bats, those mosquitoes would multiply unchecked.’

- Optative (expressing hope)

(7)

Lelakon

event

iku

that

di-gawé-a

PASS:3-make-IRR

kaca

mirror

‘Let that event become a lesson (reflection).’

- Hortative (expressing request or exhortation)

(8)

Ngombé-a

drink-IRR

banyu

water

godhogan

boiled(decoction)

‘Drink the decocted water.’

Verbs in the imperative mood cannot be preceded by an explicit subject, and are marked with the suffixes -en or -a. Intransitive verbs do not have a special imperative form.

(9)

Mripat=mu

eye=2.GEN

tutup-an-a

close-TR-IMP

‘Close your eyes.’

The propositive form is an imperative-like form used to command oneself or to express the desire to do something. The morpheme tak or dak is used before the verb to mark the active propositive mood. Unlike the pronominal prefix tak- or dak-, which cannot be preceded by a first-person subject, the active propositive construction with tak/dak can be preceded by a subject (e.g., aku tak nggorèng iwak ‘I intend to fry fish’). This active propositive marker can also be separated from the verb that follows it, as can be seen in examples (10–11).

(10)

Aku

1

tak

1.PROP

nusul

AV:follow

Bapak

father

dhéwéan

alone

‘Let me follow Dad by myself.’

(11)

Aku

1

tak

1.PROP

dhéwéan

alone

waé

PTCL

nusul

AV:follow

Bapak

father

'Let me go by myself to follow Dad.'

The suffix -é or -ipun is used to mark the passive propositive form. Here, the morpheme tak- functions similarly to the pronominal prefix tak- used in the passive form in the indicative and irrealis moods.

(12)

Tak=Ø-plathok-an-é

1=PASS:1/2-split-TR-PROP

kayu=mu

wood=2.GEN

‘Let me split your wood.’

In non-indicative forms (irrealis/subjunctive, imperative, and propositive), the suffixes -i and -aké are synonymous with the suffixes -an and -n, as in the affix sequences -an-a, -an-é, -n-a, and -n-é. These affixes are often regarded as fused forms (-ana, -ané, -na, and -né), although some linguists argue that they are actually composed of two separate components: -an and -n as derivational affixes, and -a and -é as mood markers.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2023) |

Syntax

Modern Javanese usually employs SVO word order. However, Old Javanese sometimes had VSO and sometimes VOS word order. Even in Modern Javanese, archaic sentences using VSO structure can still be made.

Examples:

- Modern Javanese: "Dhèwèké (S) teka (V) ing (pp.) karaton (O)".[57]

- Old Javanese: "Teka (V) ta (part.) sira (S) ri (pp.) -ng (def. art.) kadhatwan (O)".[i]

Both sentences mean: "He (S) comes (V) into (pp.) the (def. art.) palace (O)". In the Old Javanese sentence, the verb is placed at the beginning and is separated by the particle ta from the rest of the sentence. In Modern Javanese the definite article is lost, and definiteness is expressed by other means if necessary.

Verbs are not inflected for person or number. There is no grammatical tense; time is expressed by auxiliary words meaning "yesterday", "already", etc. There is a complex system of verb affixes to express differences of status in subject and object. However, in general the structure of Javanese sentences both Old and Modern can be described using the topic–comment model, without having to refer to conventional grammatical categories. The topic is the head of the sentence; the comment is the modifier. So the example sentence has a simpler description: Dhèwèké = topic; teka = comment; ing karaton = setting.

Remove ads

Vocabulary

Summarize

Perspective

Javanese has many loanwords supplementing those from the native Austronesian base. Sanskrit has had a deep and lasting influence. The Old Javanese–English Dictionary contains approximately 25,500 entries, over 12,600 of which are borrowings from Sanskrit.[58] Such a high number is no measure of usage, but it does suggest the extent to which the language adopted Sanskrit words for formal purposes. In a typical Old Javanese literary work about 25% of the vocabulary is from Sanskrit. Many Javanese personal names also have clearly recognisable Sanskrit roots.

Sanskrit words are still very much in use. Modern speakers may describe Old Javanese and Sanskrit words as kawi (roughly meaning "literary"); but kawi words may also be from Arabic. Dutch and Malay are influential as well; but none of these rivals the position of Sanskrit.

There are far fewer Arabic loanwords in Javanese than in Malay, and they are usually concerned with Islamic religion. Nevertheless, some words have entered the basic vocabulary, such as pikir ("to think", from the Arabic fikr), badan ("body"), mripat ("eye", thought to be derived from the Arabic ma'rifah, meaning "knowledge" or "vision"). However, these Arabic words typically have native Austronesian or Sanskrit alternatives: pikir = galih, idhep (Austronesian) and manah, cipta, or cita (from Sanskrit); badan = awak (Austronesian) and slira, sarira, or angga (from Sanskrit); and mripat = mata (Austronesian) and soca or nétra (from Sanskrit).

Dutch loanwords usually have the same form and meaning as in Indonesian, with a few exceptions such as:

The word sepur also exists in Indonesian, but there it has preserved the literal Dutch meaning of "railway tracks", while the Javanese word follows Dutch figurative use, and "spoor" (lit. "rail") is used as metonymy for "trein" (lit. "train"). (Compare a similar metonymic use in English: "to travel by rail" may be used for "to travel by train".)

Malay was the lingua franca of the Indonesian archipelago before the proclamation of Indonesian independence in 1945; and Indonesian, which was based on Malay, is now the official language of Indonesia. As a consequence, there has been an influx of Malay and Indonesian vocabulary into Javanese. Many of these words are concerned with bureaucracy or politics.

Basic vocabulary

Numbers

[Javanese Ngoko is on the left, and Javanese Krama is on the right.]

Registers

In common with other Austronesian languages, Javanese is spoken differently depending on the social context. In Austronesian languages there are often three distinct styles or registers.[60] Each employs its own vocabulary, grammatical rules, and even prosody. In Javanese these styles are called:

- Ngoko (ꦔꦺꦴꦏꦺꦴ): Vernacular or informal speech, used between friends and close relatives. It is also used by persons of higher status (such as elders, or bosses) addressing those of lower status (young people, or subordinates in the workplace).

- Madya (ꦩꦢꦾ): Intermediate between ngoko and krama. Strangers on the street would use it, where status differences may be unknown and one wants to be neither too formal nor too informal. The term is from Sanskrit madhya ("middle").[61]

- Krama (ꦏꦿꦩ): The polite, high-register, or formal style. It is used between those of the same status when they do not wish to be informal. It is used by persons of lower status to persons of higher status, such as young people to their elders, or subordinates to bosses; and it is the official style for public speeches, announcements, etc. The term is from Sanskrit krama ("in order").[61]

There are also "meta-style" honorific words, and their converse "humilifics". Speakers use "humble" words concerning themselves, but honorific words concerning anyone of greater age of higher social status. The humilific words are called krama andhap, while the honorifics are called krama inggil. This honorific system is very similar to that of the Japanese keigo. Children typically use the ngoko style, but in talking to the parents they must be competent with both krama inggil and krama andhap.

The most polite word meaning "eat" is dhahar. But it is considered inappropriate to use these most polite words for oneself, except when talking with someone of lower status; and in this case, ngoko style is used. Such most polite words are reserved for addressing people of higher status:

- Mixed usages

- (honorific – addressing someone of high status) Bapak kersa dhahar? ("Do you want to eat?"; literally "Does father want to eat?")

- (reply to a person of lower status, expressing speaker's superiority) Iya, aku kersa dhahar. ("Yes, I want to eat.")

- (reply to a person of lower status, but without expressing superiority) Iya, aku arep mangan.

- (reply to a person of equal status) Inggih, kula badhé nedha.

The use of these different styles is complicated and requires thorough knowledge of Javanese culture, which adds to the difficulty of Javanese for foreigners. The full system is not usually mastered by most Javanese themselves, who might use only the ngoko and a rudimentary form of the krama. People who can correctly use the different styles are held in high esteem.

Remove ads

Sample text

The following is a sample text in Javanese of Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Remove ads

See also

References

Sources

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads