Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

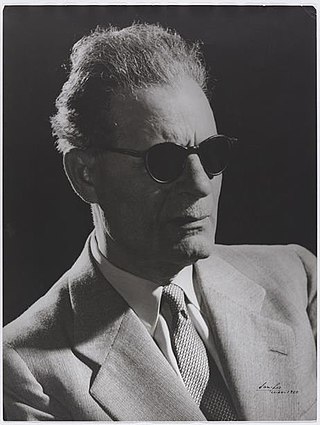

Taha Hussein

Egyptian writer (1889–1973) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Taha Hussein (Egyptian Arabic: [ˈtˤɑːhɑ ħ(e)ˈseːn], Arabic: طه حسين; November 15, 1889 – October 28, 1973) was among the most influential 20th-century Egyptian writers and intellectuals, and a leading figure of the Arab Renaissance and the modernist movement in the Arab world.[2] His sobriquet was "The Dean of Arabic Literature" (Arabic: عميد الأدب العربي).[3][4] He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature twenty-one times.[5]

Remove ads

Early life

Taha Hussein was born in Izbet el Kilo, a village in the Minya Governorate in central Upper Egypt.[1] He was the seventh of thirteen children of lower middle class Muslim parents.[1] He contracted ophthalmia at the age of two, and became blind as a result of malpractice by an unskilled physician.[6][7] After attending a kuttab, he studied religion and Arabic literature at El Azhar University; but from an early age, he was dissatisfied with the traditional education system.

When the secular Cairo University was founded in 1908, he was keen to be admitted, and despite being poor and blind, he won a place. In 1914, he received a PhD for his thesis on the sceptic poet and philosopher Abu al-ʿAlaʾ al-Maʿarri.[6]

Remove ads

Taha Hussein in France

Taha Hussein left for Montpellier, enrolled in its university, attended courses in literature, history, French and Latin. He had studied formal writing, but he was not able to take full advantage of it as he "may be used to taking knowledge with his ears, not with his fingers."[8]

He was summoned to return to Egypt due to the poor conditions at then University of Cairo; but three months later, those conditions improved, and Taha Hussein returned to France.[8]

After obtaining his MA from the University of Montpellier, Hussein continued his studies at the Sorbonne University. He hired Suzanne Bresseau (1895–1989) to read to him, and subsequently married her.[7][8] In 1917, the Sorbonne awarded Hussein a second PhD, this time for his dissertation on the Tunisian historian Ibn Khaldun, who is regarded as one of the founders of sociology.

Remove ads

Academic career

Summarize

Perspective

In 1919, Hussein returned to Egypt with Suzanne, and he was appointed professor of history at Cairo University.[7] He went on to become a professor of Arabic literature and of Semitic languages.[9]

At the Academy of the Arabic Language in Cairo, Taha Hussein was made responsible for the completion of Al-Mu'jam al-Kabir (The Great Dictionary), one of the academy's most important tasks.[9] He also served as president of the academy.[10]

Taha Hussein was a member of several scientific academies in Egypt and internationally. He was also the founding Rector of the University of Alexandria.

A work of literary criticism, On Pre-Islamic Poetry (في الشعر الجاهلي), published in 1926, brought him fame and some notoriety in the Arab world.[11] In this book, Hussein expressed doubt about the authenticity of much early Arabic poetry, claiming it to have been falsified during ancient times due to tribal pride and inter-tribal rivalries. He also hinted indirectly that the Qur'an should not be taken as an objective source of history.[6] Consequently, the book aroused the intense anger and hostility of religious scholars at Al Azhar as well as other traditionalists, and he was accused of having insulted Islam. The public prosecutor stated, however, that what Taha Hussein had said was the opinion of an academic researcher; no legal action was taken against him, although he lost his post at Cairo University in 1931. His book was banned but was re-published the next year with slight modifications under the title On Pre-Islamic Literature (1927).[6]

Political career

Summarize

Perspective

Taha Hussein was an intellectual of a modern Egyptian renaissance in the early to mid 20th century and a proponent of the ideology of Egyptian nationalism. Although famed as the Dean of Arabic Literature, Taha Hussein was an Egyptian nationalist who rejected pan-Arabism. In his book The Future of Culture in Egypt, published in 1936, Hussein stated that "For Egyptians, Arabic is virtually a foreign language; nobody speaks it at home, school, in the streets, or in clubs. [...] People everywhere speak a language that is not Arabic, despite the partial resemblance to it."[12] In opposition to the Pan-Arabists, Hussein asserted that most Egyptians were descendants of the Ancient Egyptians and did not possess any Arab blood, and that Arabic as a daily language in Egypt should not determine the fate of a nation.[13]

Hussein criticized the lack of freedom in Nazi Germany, writing: "They live like a society of insects. They must behave like ants in an anthill or like bees in a hive." Hussein urged the Egyptian government to reject neutrality and fight the Germans in the war.[14]

In 1950, he was appointed Minister of Education, in which capacity he led a call for free education and the right of everyone to be educated.[7] He also transformed many of the Quranic schools into primary schools and converted a number of high schools into colleges such as the Graduate Schools of Medicine and Agriculture. In addition, he is credited with establishing a number of new universities and he was the head of the Cultural Heritage of the Ministry of Education.[9] Hussein proposed that Al-Azhar University should be closed down in 1955 after his tenure as education minister ended.[15]

Remove ads

Works

Summarize

Perspective

In the West, he is best known for his autobiography, Al-Ayyam (الأيام, The Days) which was published in English as An Egyptian Childhood (1932) and The Stream of Days (1943).

The author of "more than sixty books (including six novels) and 1,300 articles",[16] his major works include:[17]

- The Memory of Abu al-Ala' al-Ma'arri (1915)

- Selected Poetical Texts of the Greek Drama (1924)

- Dramas by a Group of the Most Famous French Writers (1924)

- Ibn Khaldun's Philosophy (1925)

- Pioneers of Thoughts (1925)

- Wednesday Talk (1925)

- On Pre-Islamic Poetry (1926)

- In the Summer (1933)

- The Days (1926–1967)

- Hafez and Shawki (1933)

- The Prophet's Life (1933)

- Curlew's Prayers (1934)

- From a Distance (1935)

- Adeeb (1935)

- The Literary Life in the Arabian Peninsula (1935)

- Together with Abi El Alaa in His Prison (1935)

- Poetry and Prose (1936)

- Bewitched Palace (1937)

- Together with El Motanabi (1937)

- The Future of Culture in Egypt (1938)

- Moments (1942)

- The Voice of Paris (1943)

- Sheherzad's Dreams (1943)

- Tree of Misery (1944)

- Paradise of Thorn (1945)

- Chapters on Literature and Criticism (1945)

- The Voice of Abu El Alaa (1945)

- Al-Fitna al-Kubra (The Great Upheaval) (1947)

- Spring Journey (1948)

- The Stream Of Days (1948)

- The Tortured of Modern Conscience (1949)

- The Divine Promise (1950)

- The Paradise of Animals (1950)

- The Lost Love (1951)

- From There (1952)

- Varieties (1952)

- In The Midst (1952)

- Osman: The First Part of the Greater Sedition (1952)

- Ali and His Sons: The 2nd Part of the Greater Sedition (1953)

- Sharh Lozoum Mala Yalzm (1955)

- Anatagonism and Reform (1955)

- The Sufferers: Stories and Polemics (Published in Arabic in 1955), Translated by Mona El-Zayyat (1993), Published by The American University in Cairo, ISBN 9774242998

- Criticism and Reform (1956)

- Our Contemporary Literature (1958)

- Mirror of Islam (1959)

- Summer Nonsense (1959)

- On the Western Drama (1959)

- Talks (1959)

- Al-Shaikhan (Abu Bakr and Omar Ibn al-Khattab) (1960)

- From Summer Nonsense to Winter Seriousness (1961)

- Reflections (1965)

- Beyond the River (1975)

- Words (1976)

- Tradition and Renovation (1978)

- Books and Author (1980)

- From the Other Shore (1980)

Translations

- Jules Simon's The Duty (1920–1921)

- Athenians System (1921)

- The Spirit of Pedagogy (1921)

- Dramatic Tales (1924)

- Jean Racine's Andromaque (1935)

- From the Greek Dramatic Literature (Sophocles) (1939)

- Voltaire's Zadig or (The Fate) (1947)

- André Gide: From Greek

- Legends' Heroes

- Sophocle-Oedipe

Remove ads

Tribute

On November 14, 2010, Google celebrated Hussein's 121st birthday with a Google Doodle.[18]

Honours

Remove ads

See also

- Taha Hussein Museum – Historic house and biographical museum in Cairo

- List of Egyptian authors

- His page at arabworldbooks.com

- His complete works at hindawi.org (in Arabic)

External links

Wikiquote has quotations related to Taha Hussein.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Creator:Taha Hussein.

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads