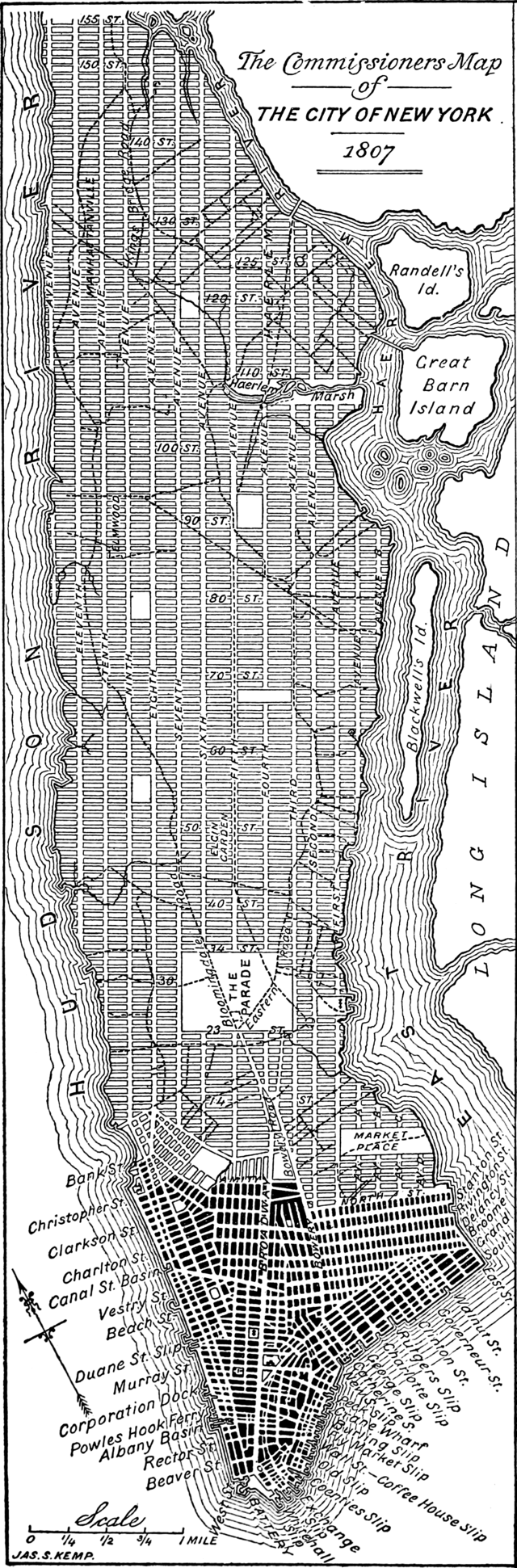

Commissioners' Plan of 1811

Street plan of Manhattan / From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Dear Wikiwand AI, let's keep it short by simply answering these key questions:

Can you list the top facts and stats about Commissioners' Plan of 1811?

Summarize this article for a 10 year old

The Commissioners' Plan of 1811 was the original design for the streets of Manhattan above Houston Street and below 155th Street, which put in place the rectangular grid plan of streets and lots that has defined Manhattan on its march uptown until the current day. It has been called "the single most important document in New York City's development,"[1] and the plan has been described as encompassing the "republican predilection for control and balance ... [and] distrust of nature".[2] It was described by the Commission that created it as combining "beauty, order and convenience."[2]

The plan originated when the Common Council of New York City, seeking to provide for the orderly development and sale of the land of Manhattan between 14th Street and Washington Heights, but unable to do so itself for reasons of local politics and objections from property owners, asked the New York State Legislature to step in. The legislature appointed a commission with sweeping powers in 1807, and their plan was presented in 1811.

The Commissioners were Gouverneur Morris, a Founding Father of the United States; the lawyer John Rutherfurd, a former United States Senator; and the state Surveyor General, Simeon De Witt. Their chief surveyor was John Randel Jr., who was 20 years old when he began the job.

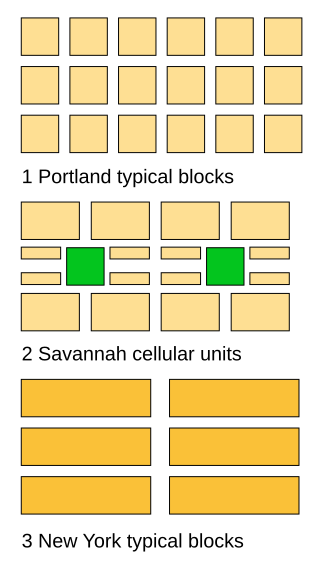

The Commissioners' Plan is arguably the most famous use of the grid plan or "gridiron" and is considered by many historians to have been far-reaching and visionary. Since its earliest days, the plan has been criticized for its monotony and rigidity, in comparison with irregular street patterns of older cities, but in recent years has been viewed more favorably by urban planners.[3]

There were a few interruptions in the grid for public spaces, such as the Grand Parade between 23rd Street and 33rd Street, which was the precursor to Madison Square Park, as well as four squares named Bloomingdale, Hamilton, Manhattan, and Harlem, a wholesale market complex, and a reservoir.[4][2][5] Central Park, the massive urban greenspace in Manhattan running from Fifth Avenue to Eighth Avenue and from 59th Street to 110th Street, was not a part of the plan, as it was not envisioned until the 1850s. The numbering was also extended through Manhattan and the Bronx.