Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Ptolemy

Astronomer and geographer (c. 100–170) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Claudius Ptolemy (/ˈtɒləmi/; Ancient Greek: Πτολεμαῖος, Ptolemaios; Latin: Claudius Ptolemaeus; c. 100 – 160s/170s AD),[1] better known mononymously as Ptolemy, was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist[2] who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine, Islamic, and Western European science. The first was his astronomical treatise now known as the Almagest, originally entitled Mathēmatikḗ Syntaxis (Μαθηματικὴ Σύνταξις, Mathēmatikḗ Syntaxis, lit. 'Mathematical Treatise'). The second is the Geography, which is a thorough discussion on maps and the geographic knowledge of the Greco-Roman world. The third is the astrological treatise in which he attempted to adapt horoscopic astrology to the Aristotelian natural philosophy of his day. This is sometimes known as the Apotelesmatika (Αποτελεσματικά, 'On the Effects') but more commonly known as the Tetrábiblos (from the Koine Greek meaning 'four books'; Latin: Quadripartitum).

The Catholic Church promoted his work, which included the only mathematically sound geocentric model of the Solar System, and unlike most Greek mathematicians, Ptolemy's writings (foremost the Almagest) never ceased to be copied or commented upon, both in late antiquity and in the Middle Ages. However, it is likely that only a few truly mastered the mathematics necessary to understand his works, as evidenced particularly by the many abridged and watered-down introductions to Ptolemy's astronomy that were popular among the Arabs and Byzantines. His work on epicycles is now seen as a very complex theoretical model built in order to explain a false tenet based on faith.

Remove ads

Biography

Summarize

Perspective

Ptolemy's date of birth and birthplace are both unknown. The 14th-century astronomer Theodore Meliteniotes wrote that Ptolemy's birthplace was Ptolemais Hermiou, a Greek city in the Thebaid region of Egypt (now El Mansha, Sohag Governorate). This attestation is quite late, however, and there is no evidence to support it.[3][b]

It is known that Ptolemy lived in or around the city of Alexandria, in the Roman province of Egypt under Roman rule.[5] He had a Latin name, Claudius, which is generally taken to imply he was a Roman citizen.[6] He was familiar with Greek philosophers and used Babylonian observations and Babylonian lunar theory. In half of his extant works, Ptolemy addresses a certain Syrus, a figure of whom almost nothing is known but who likely shared some of Ptolemy's astronomical interests.[7]

Ptolemy died in Alexandria.[8](p311) Ptolemy's year of death is not directly recorded by primary sources, and has to be inferred from the scale of his work.[9] Suggested years of death include c. 165,[10] c. 168,[8](p311) c. 170,[9] and c. 175.[11]

Naming and nationality

Ptolemy's Greek name, Ptolemaeus (Πτολεμαῖος, Ptolemaîos), is an ancient Greek personal name. It occurs once in Greek mythology and is of Homeric form.[12] It was common among the Macedonian upper class at the time of Alexander the Great and there were several of this name among Alexander's army, one of whom made himself pharaoh in 323 BC: Ptolemy I Soter, the first pharaoh of the Ptolemaic Kingdom. Almost all subsequent pharaohs of Egypt, with a few exceptions, were named Ptolemy until Egypt became a Roman province in 30 BC, ending the Macedonian family's rule.[13]

The name Claudius is a Roman name, belonging to the gens Claudia; the peculiar multipart form of the whole name Claudius Ptolemaeus is a Roman custom, characteristic of Roman citizens. This indicates that Ptolemy would have been a Roman citizen.[3] Gerald Toomer, the translator of Ptolemy's Almagest into English, suggests that citizenship was probably granted to one of Ptolemy's ancestors by either the emperor Claudius or the emperor Nero.[14]

The 9th century Persian astronomer Abu Ma'shar al-Balkhi mistakenly presents Ptolemy as a member of Ptolemaic Egypt's royal lineage, stating that the descendants of the Alexandrine general and Pharaoh Ptolemy I Soter were wise "and included Ptolemy the Wise, who composed the book of the Almagest". Abu Ma'shar recorded a belief that a different member of this royal line "composed the book on astrology and attributed it to Ptolemy". Historical confusion on this point can be inferred from Abu Ma'shar's subsequent remark: "It is sometimes said that the very learned man who wrote the book of astrology also wrote the book of the Almagest. The correct answer is not known."[15] Not much positive evidence is known on the subject of Ptolemy's ancestry, apart from what can be drawn from the details of his name, although modern scholars have concluded that Abu Ma'shar's account is erroneous.[17] It is no longer doubted that the astronomer who wrote the Almagest also wrote the Tetrabiblos as its astrological counterpart.[18](p x) In later Arabic sources, he was often known as "the Upper Egyptian",[19][20](p 606) suggesting he may have had origins in southern Egypt.[20](pp 602, 606) Arabic astronomers, geographers, and physicists referred to his name in Arabic as Baṭlumyus (Arabic: بَطْلُمْيوس).[21]

Ptolemy wrote in Koine Greek,[22] and can be shown to have used Babylonian astronomical data.[23][24](p 99) He might have been a Roman citizen, but was ethnically either a Greek[1][25][26] or at least a Hellenized Egyptian.[c][27][28]

Remove ads

Astronomical writings

Summarize

Perspective

Astronomy was the subject to which Ptolemy devoted the most time and effort; about half of all the works that survived deal with astronomical matters, and even others such as the Geography and the Tetrabiblos have significant references to astronomy.[29]

Mathēmatikē Syntaxis

Ptolemy's Almagest (originally Ancient Greek: Μαθηματικὴ Σύνταξις, romanized: Mathēmatikē Syntaxis, lit. 'Mathematical Systematic Treatise') is the only surviving comprehensive ancient treatise on astronomy. Although Babylonian astronomers had developed arithmetical techniques for calculating and predicting astronomical phenomena, these were not based on any underlying model of the heavens; early Greek astronomers, on the other hand, provided qualitative geometrical models to "save the appearances" of celestial phenomena without the ability to make any predictions.[30]

The earliest person who attempted to merge these two approaches was Hipparchus, who produced geometric models that not only reflected the arrangement of the planets and stars but could be used to calculate celestial motions.[24] Ptolemy, following Hipparchus, derived each of his geometrical models for the Sun, Moon, and the planets from selected astronomical observations done in the spanning of more than 800 years; however, many astronomers have for centuries suspected that some of his models' parameters were adopted independently of observations.[31]

Ptolemy presented his astronomical models alongside convenient tables, which could be used to compute the future or past position of the planets.[32] The Almagest also contains a star catalogue, which is a version of a catalogue created by Hipparchus. Its list of forty-eight constellations is ancestral to the modern system of constellations but, unlike the modern system, they did not cover the whole sky (only what could be seen with the naked eye in the northern hemisphere).[33] For over a thousand years, the Almagest was the authoritative text on astronomy across Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa.[34]

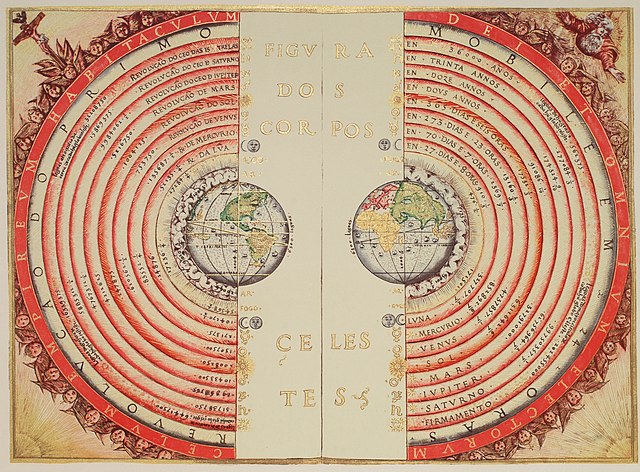

The Almagest was preserved, like many extant Greek scientific works, in Arabic manuscripts; the modern title is thought to be an Arabic corruption of the Greek name Hē Megistē Syntaxis ('The greatest treatise'), as the work was presumably known during late antiquity.[35] Because of its reputation, it was widely sought and translated twice into Latin in the 12th century, once in Sicily and again in Spain.[36] Ptolemy's planetary models, like those of the majority of his predecessors, were geocentric and almost universally accepted until the reappearance of heliocentric models during the Scientific Revolution.

Modern reassessment

Under the scrutiny of modern scholarship, and the cross-checking of observations contained in the Almagest against figures produced through backwards extrapolation, various patterns of errors have emerged within the work.[37][38] A prominent miscalculation is Ptolemy's use of measurements that he claimed were taken at noon, but which systematically produce readings now shown to be off by half an hour, as if the observations were taken at 12:30 pm.[37]

The overall quality of Ptolemy's observations has been challenged by several modern scientists, but prominently by Robert R. Newton in his 1977 book The Crime of Claudius Ptolemy, which asserted that Ptolemy fabricated many of his observations to fit his theories.[39] Newton accused Ptolemy of systematically inventing data or doctoring the data of earlier astronomers, and labelled him "the most successful fraud in the history of science".[37] One striking error noted by Newton was an autumn equinox said to have been observed by Ptolemy and "measured with the greatest care" at 2pm on 25 September 132, when the equinox should have been observed around 9:55am the day prior.[37] In attempting to disprove Newton, Herbert Lewis also found himself agreeing that "Ptolemy was an outrageous fraud,"[38] and that "all those result capable of statistical analysis point beyond question towards fraud and against accidental error".[38]

The charges laid by Newton and others have been the subject of wide discussions and received significant push back from other scholars against the findings.[37] Owen Gingerich, while agreeing that the Almagest contains "some remarkably fishy numbers",[37] including in the matter of the 30-hour displaced equinox, which he noted aligned perfectly with predictions made by Hipparchus 278 years earlier,[40] rejected the qualification of fraud.[37] Objections were also raised by Bernard Goldstein, who questioned Newton's findings and suggested that he had misunderstood the secondary literature, while noting that issues with the accuracy of Ptolemy's observations had long been known.[39] Other authors have pointed out that instrument warping or atmospheric refraction may also explain some of Ptolemy's observations at a wrong time.[41][42]

In 2022 the first Greek fragments of Hipparchus' lost star catalog were discovered in a palimpsest and they debunked accusations made by the French astronomer Jean Baptiste Joseph Delambre in the early 1800s which were repeated by R. R. Newton. Specifically, it proved Hipparchus was not the sole source of Ptolemy's catalog, as they both had claimed, and proved that Ptolemy did not simply copy Hipparchus' measurements and adjust them to account for precession of the equinoxes, as they had claimed. Scientists analyzing the charts concluded:

It also confirms that Ptolemy’s Star Catalogue was not based solely on data from Hipparchus’ Catalogue.

... These observations are consistent with the view that Ptolemy composed his star catalogue by combining various sources, including Hipparchus’ catalogue, his own observations and, possibly, those of other authors.[43]

Handy Tables

The Handy Tables (Greek: Πρόχειροι κανόνες) are a set of astronomical tables, together with canons for their use. To facilitate astronomical calculations, Ptolemy tabulated all the data needed to compute the positions of the Sun, Moon and planets, the rising and setting of the stars, and eclipses of the Sun and Moon, making it a useful tool for astronomers and astrologers. The tables themselves are known through Theon of Alexandria's version. Although Ptolemy's Handy Tables do not survive as such in Arabic or in Latin, they represent the prototype of most Arabic and Latin astronomical tables or zījes.[44]

Additionally, the introduction to the Handy Tables survived separately from the tables themselves (apparently part of a gathering of some of Ptolemy's shorter writings) under the title Arrangement and Calculation of the Handy Tables.[45]

Planetary Hypotheses

The Planetary Hypotheses (Greek: Ὑποθέσεις τῶν πλανωμένων, lit. 'Hypotheses of the Planets') is a cosmological work, probably one of the last written by Ptolemy, in two books dealing with the structure of the universe and the laws that govern celestial motion.[46] Ptolemy goes beyond the mathematical models of the Almagest to present a physical realization of the universe as a set of nested spheres,[47] in which he used the epicycles of his planetary model to compute the dimensions of the universe. He estimated the Sun was at an average distance of 1210 Earth radii (now known to actually be ~23450 radii), while the radius of the sphere of the fixed stars was 20000 times the radius of the Earth.[48]

The work is also notable for having descriptions on how to build instruments to depict the planets and their movements from a geocentric perspective, much as an orrery would have done for a heliocentric one, presumably for didactic purposes.[49]

Other astronomical works

The Analemma is a short treatise where Ptolemy provides a method for specifying the location of the Sun in three pairs of locally oriented coordinate arcs as a function of the declination of the Sun, the terrestrial latitude, and the hour. The key to the approach is to represent the solid configuration in a plane diagram that Ptolemy calls the analemma.[50]

In another work, the Phaseis (Risings of the Fixed Stars), Ptolemy gave a parapegma, a star calendar or almanac, based on the appearances and disappearances of stars over the course of the solar year.[51]

The Planisphaerium (Greek: Ἅπλωσις ἐπιφανείας σφαίρας, lit. 'Flattening of the sphere') contains 16 propositions dealing with the projection of the celestial circles onto a plane. The text is lost in Greek (except for a fragment) and survives in Arabic and Latin only.[52]

Ptolemy also erected an inscription in a temple at Canopus, around 146–147 AD, known as the Canobic Inscription. Although the inscription has not survived, someone in the sixth century transcribed it, and manuscript copies preserved it through the Middle Ages. It begins: "To the saviour god, Claudius Ptolemy (dedicates) the first principles and models of astronomy", following by a catalogue of numbers that define a system of celestial mechanics governing the motions of the Sun, Moon, planets, and stars.[53]

In 2023, archaeologists were able to read a manuscript which gives instructions for the construction of an astronomical tool called a meteoroscope (μετεωροσκόπιον or μετεωροσκοπεῖον). The text, which comes from an eighth-century manuscript which also contains Ptolemy's Analemma, was identified on the basis of both its content and linguistic analysis as being by Ptolemy.[54][55]

Ptolemy is also though to have produced his Table of Noteworthy Cities as an aid to his astronomical tables.[56]

Remove ads

Other writings

Summarize

Perspective

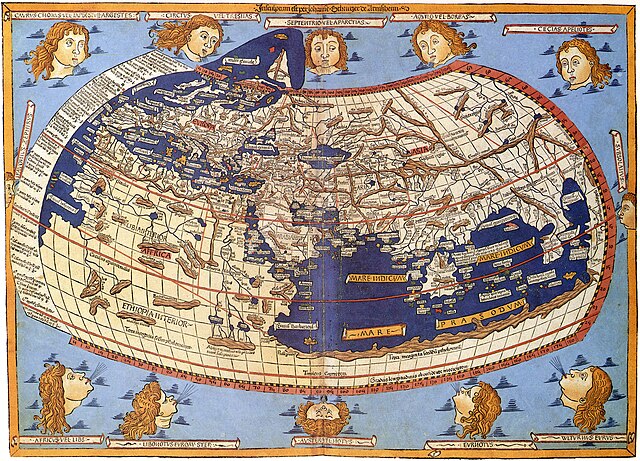

Geography

Ptolemy's second most well-known work is his Geographike Hyphegesis (Greek: Γεωγραφικὴ Ὑφήγησις; lit. 'Guide to Drawing the Earth'), known as the Geography, a handbook on how to draw maps using geographical coordinates for parts of the Roman world known at the time.[57][58] He relied on previous work by an earlier geographer, Marinus of Tyre, as well as on gazetteers of the Roman and ancient Persian Empire.[58][57] He also acknowledged ancient astronomer Hipparchus for having provided the elevation of the north celestial pole[59] for a few cities. Although maps based on scientific principles had been made since the time of Eratosthenes (c. 276 – c. 195 BC), Ptolemy improved on map projections.

The first part of the Geography is a discussion of the data and of the methods he used. Ptolemy notes the supremacy of astronomical data over land measurements or travelers' reports, though he possessed these data for only a handful of places. Ptolemy's real innovation, however, occurs in the second part of the book, where he provides a catalogue of 8,000 localities he collected from Marinus and others, the biggest such database from antiquity.[60] About 6300 of these places and geographic features have assigned coordinates so that they can be placed in a grid that spanned the globe.[29] Latitude was measured from the equator, as it is today, but Ptolemy preferred to express it as climata, the length of the longest day rather than degrees of arc: The length of the midsummer day increases from 12h to 24h as one goes from the equator to the polar circle.[61] One of the places Ptolemy noted specific coordinates for was the now-lost stone tower which marked the midpoint on the ancient Silk Road, and which scholars have been trying to locate ever since.[62]

In the third part of the Geography, Ptolemy gives instructions on how to create maps both of the whole inhabited world (oikoumenē) and of the Roman provinces, including the necessary topographic lists, and captions for the maps. His oikoumenē spanned 180 degrees of longitude from the Blessed Islands in the Atlantic Ocean to the middle of China, and about 80 degrees of latitude from Shetland to anti-Meroe (east coast of Africa); Ptolemy was well aware that he knew about only a quarter of the globe, and an erroneous extension of China southward suggests his sources did not reach all the way to the Pacific Ocean.[57][58]

It seems likely that the topographical tables in the second part of the work (Books 2–7) are cumulative texts, which were altered as new knowledge became available in the centuries after Ptolemy.[63] This means that information contained in different parts of the Geography is likely to be of different dates, in addition to containing many scribal errors. However, although the regional and world maps in surviving manuscripts date from c. 1300 AD (after the text was rediscovered by Maximus Planudes), there are some scholars who think that such maps go back to Ptolemy himself.[60]

Tetrabiblos

Ptolemy wrote an astrological treatise, in four parts, known by the Greek term Tetrabiblos (lit. 'Four Books') or by its Latin equivalent Quadripartitum.[64] Its original title is unknown, but may have been a term found in some Greek manuscripts, Apotelesmatiká (biblía), roughly meaning "(books) on the Effects" or "Outcomes", or "Prognostics".[18](p x) As a source of reference, the Tetrabiblos is said to have "enjoyed almost the authority of a Bible among the astrological writers of a thousand years or more".[18](p xii) It was first translated from Arabic into Latin by Plato of Tivoli (Tiburtinus) in 1138, while he was in Spain.[65]

Much of the content of the Tetrabiblos was collected from earlier sources; Ptolemy's achievement was to order his material in a systematic way, showing how the subject could, in his view, be rationalized. It is, indeed, presented as the second part of the study of astronomy of which the Almagest was the first, concerned with the influences of the celestial bodies in the sublunary sphere.[16][17] Thus explanations of a sort are provided for the astrological effects of the planets, based upon their combined effects of heating, cooling, moistening, and drying.[66] Ptolemy dismisses other astrological practices, such as considering the numerological significance of names, that he believed to be without sound basis, and leaves out popular topics, such as electional astrology (interpreting astrological charts to determine courses of action) and medical astrology, for similar reasons.[67]

The great respect in which later astrologers held the Tetrabiblos derived from its nature as an exposition of theory, rather than as a manual.[67]

A collection of one hundred aphorisms about astrology called the Centiloquium, ascribed to Ptolemy, was widely reproduced and commented on by Arabic, Latin, and Hebrew scholars, and often bound together in medieval manuscripts after the Tetrabiblos as a kind of summation.[29] It is now believed to be a much later pseudepigraphical composition. The identity and date of the actual author of the work, referred to now as Pseudo-Ptolemy, remains the subject of conjecture.[68]

Harmonics

Ptolemy's Harmonics (Greek: Ἁρμονικόν) is a work in three books on music theory and the mathematics behind musical scales[69]

Harmonics begins with a definition of harmonic theory, with a long exposition on the relationship between reason and sense perception in corroborating theoretical assumptions. After criticizing the approaches of his predecessors, Ptolemy argues for basing musical intervals on mathematical ratios (as opposed to the ideas advocated by followers of Aristoxenus), backed up by empirical observation (in contrast to the excessively theoretical approach of the Pythagoreans).[70][71]

Ptolemy introduces the harmonic canon (Greek name) or monochord (Latin name), which is an experimental musical apparatus that he used to measure relative pitches, and used to describe to his readers how to demonstrate the relations discussed in the following chapters for themselves. After the early exposition on to build and use monochord to test proposed tuning systems, Ptolemy proceeds to discuss Pythagorean tuning (and how to demonstrate that their idealized musical scale fails in practice). The Pythagoreans believed that the mathematics of music should be based on only the one specific ratio of 3:2, the perfect fifth, and believed that tunings mathematically exact to their system would prove to be melodious, if only the extremely large numbers involved could be calculated (by hand). To the contrary, Ptolemy believed that musical scales and tunings should in general involve multiple different ratios arranged to fit together evenly into smaller tetrachords (combinations of four pitch ratios which together make a perfect fourth) and octaves.[72][73] Ptolemy reviewed standard (and ancient, disused) musical tuning practice of his day, which he then compared to his own subdivisions of the tetrachord and the octave, which he derived experimentally using a monochord / harmonic canon. The volume ends with a more speculative exposition of the relationships between harmony, the soul (psyche), and the planets (harmony of the spheres).[74]

Although Ptolemy's Harmonics never had the influence of his Almagest or Geography, it is nonetheless a well-structured treatise and contains more methodological reflections than any other of his writings. In particular, it is a nascent form of what in the following millennium developed into the scientific method, with specific descriptions of the experimental apparatus that he built and used to test musical conjectures, and the empirical musical relations he identified by testing pitches against each other: He was able to accurately measure relative pitches based on the ratios of vibrating lengths two separate sides of the same single string, hence which were assured to be under equal tension, eliminating one source of error. He analyzed the empirically determined ratios of "pleasant" pairs of pitches, and then synthesised all of them into a coherent mathematical description, which persists to the present as just intonation – the standard for comparison of consonance in the many other, less-than exact but more facile compromise tuning systems.[75][76]

During the Renaissance, Ptolemy's ideas inspired Kepler in his own musings on the harmony of the world (Harmonice Mundi, Appendix to Book V).[77]

Optics

The Optica (Koine Greek: Ὀπτικά), known as the Optics, is a work that survives only in a somewhat poor Latin version, which, in turn, was translated from a lost Arabic version by Eugenius of Palermo (c. 1154). In it, Ptolemy writes about properties of sight (not light), including reflection, refraction, and colour. The work is a significant part of the early history of optics and influenced the more famous and superior 11th-century Book of Optics by Ibn al-Haytham.[78] Ptolemy offered explanations for many phenomena concerning illumination and colour, size, shape, movement, and binocular vision. He also divided illusions into those caused by physical or optical factors and those caused by judgmental factors. He offered an obscure explanation of the Sun or Moon illusion (the enlarged apparent size on the horizon) based on the difficulty of looking upwards.[79][80]

The work is divided into three major sections. The first section (Book II) deals with direct vision from first principles and ends with a discussion of binocular vision. The second section (Books III-IV) treats reflection in plane, convex, concave, and compound mirrors.[81] The last section (Book V) deals with refraction and includes the earliest surviving table of refraction from air to water, for which the values (with the exception of the 60° angle of incidence) show signs of being obtained from an arithmetic progression.[82] However, according to Mark Smith, Ptolemy's table was based in part on real experiments.[83]

Ptolemy's theory of vision consisted of rays (or flux) coming from the eye forming a cone, the vertex being within the eye, and the base defining the visual field. The rays were sensitive, and conveyed information back to the observer's intellect about the distance and orientation of surfaces. Size and shape were determined by the visual angle subtended at the eye combined with perceived distance and orientation.[78][84] This was one of the early statements of size-distance invariance as a cause of perceptual size and shape constancy, a view supported by the Stoics.[85]

Remove ads

Philosophy

Summarize

Perspective

Although mainly known for his contributions to astronomy and other scientific subjects, Ptolemy also engaged in epistemological and psychological discussions across his corpus.[86] He wrote a short essay entitled On the Criterion and Hegemonikon (Greek: Περὶ Κριτηρίου καὶ Ἡγεμονικοῡ), which may have been one of his earliest works. Ptolemy deals specifically with how humans obtain scientific knowledge (i.e., the "criterion" of truth), as well as with the nature and structure of the human psyche or soul, particularly its ruling faculty (i.e., the hegemonikon).[74] Ptolemy argues that, to arrive at the truth, one should use both reason and sense perception in ways that complement each other. On the Criterion is also noteworthy for being the only one of Ptolemy's works that is devoid of mathematics.[87]

Elsewhere, Ptolemy affirms the supremacy of mathematical knowledge over other forms of knowledge. Like Aristotle before him, Ptolemy classifies mathematics as a type of theoretical philosophy; however, Ptolemy believes mathematics to be superior to theology or metaphysics because the latter are conjectural while only the former can secure certain knowledge. This view is contrary to the Platonic and Aristotelian traditions, where theology or metaphysics occupied the highest honour.[86] Despite being a minority position among ancient philosophers, Ptolemy's views were shared by other mathematicians such as Hero of Alexandria.[88]

Remove ads

Named after Ptolemy

There are several characters and items named after Ptolemy, including:

- The crater Ptolemaeus on the Moon

- The crater Ptolemaeus on Mars

- The asteroid 4001 Ptolemaeus

- Messier 7, sometimes known as the Ptolemy Cluster, an open cluster of stars in the constellation of Scorpius

- The Ptolemy stone used in the mathematics courses at both St. John's College campuses in the U.S.

- Ptolemy's theorem on distances in a cyclic quadrilateral, and its generalization, Ptolemy's inequality, to non-cyclic quadrilaterals

- Ptolemaic graphs, the graphs whose distances obey Ptolemy's inequality

- Ptolemy Project, a project at University of California, Berkeley, aimed at modeling, simulating and designing concurrent, real-time, embedded systems

- Ptolemy Slocum, actor

Remove ads

See also

- Equant

- Messier 7 – Ptolemy Cluster, star cluster described by Ptolemaeus

- Pei Xiu

- Ptolemy's Canon – a dated list of kings used by ancient astronomers.

- Ptolemy's table of chords

- Zhang Heng

Notes

Bibliography

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads