Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

1959 Nobel Prize in Literature

Award From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

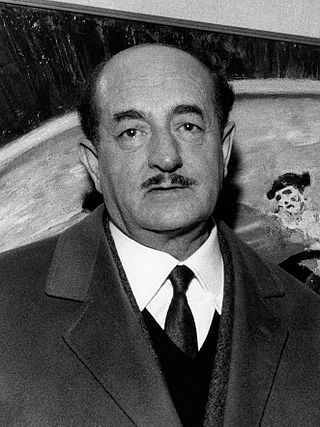

The 1959 Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to the Italian poet Salvatore Quasimodo (1901–1968) "for his lyrical poetry, which with classical fire expresses the tragic experience of life in our own times"[1] He is the fourth Italian recipient of the said prize.[2]

Remove ads

Laureate

Salvatore Quasimodo was an Italian poet, critic and translator. He published his first poetry in Nuovo giornale letterario ("New Literary Journal"), which he created in 1917. His first collection of poems, Acque e terre ("Waters and Lands"), appeared in 1930, and beginning in 1938, he devoted himself entirely to writing. The two schools of poetry that are typically used to categorize his work are hermetic and post-hermetic. World War II caused a shift in the poet's style. Hermetic poetry rejected the use of words as a means of verbal coercion and believed that words have a subjective meaning that is determined more by their sound than by their actual meaning.[3] Along with Giuseppe Ungaretti and Eugenio Montale, he was one of the foremost Italian poets of the 20th century.[3][4]

Remove ads

Deliberations

Summarize

Perspective

Nominations

Salvatore Quasimodo was nominated for the Nobel prize in literature twice, in 1958 (by 3 different nominators), and in 1959.[5]

In total, the Nobel committee received 83 nominations for 56 authors, including nominations for Saint-John Perse (awarded in 1960), Ivo Andrić (awarded in 1961), John Steinbeck (awarded in 1962), Jean-Paul Sartre (awarded in 1964), Karen Blixen, André Malraux, Romulo Gallegos, Carl Sandburg, Graham Greene, Aldous Huxley, John Cowper Powys, Alberto Moravia, Ignazio Silone, Ezra Pound, E. M. Forster, Ramón Menéndez Pidal, Martin Buber, William Somerset Maugham, Thornton Wilder and Tarjei Vesaas. Twenty of the nominees were new recommendations, including Ernest Claes, Osbert Sitwell, Sacheverell Sitwell, Martin Heidegger, Juana de Ibarbourou, Heimito von Doderer, María Raquel Adler, Miguel Torga, Arnold Zweig, Étienne Gilson, Louis Aragon, Anna Seghers, Frank Raymond Leavis, Max Frisch and Julien Gracq. Most nominations, seven, were submitted for the Polish author Maria Dabrowska. There were women nominated namely: Elizabeth Goudge, Maria Dabrowska, Juana de Ibarbourou, Karen Blixen, Anna Seghers, Edith Sitwell, Gertrud von le Fort and María Raquel Adler.[6]

The authors Maxwell Anderson, Emil František Burian, Raymond Chandler, G. D. H. Cole, Laxmi Prasad Devkota, Laurence Housman, Hans Henny Jahnn, Edwin Muir, Luis Palés Matos, Benjamin Péret, Marta Rădulescu, Alfred Schütz, Galaktion Tabidze, José Vasconcelos, Boris Vian, Arthur Henry Ward (known as Sax Rohmer) and Percy F. Westerman died in 1959 without having been nominated for the prize.

Remove ads

Prize decision

Summarize

Perspective

The Nobel committee was almost unanimous to propose that the Danish author Karen Blixen should be awarded the 1959 Nobel Prize in Literature. Committee chairman Anders Österling advocated a prize for Blixen, citing her "undubitable masterpiece" Out of Africa, and her short stories in which "she has created her own genre," that "at the high points are shining with ingenious fantasy and spiritual human knowledge". Two other members of the Nobel committee also supported a prize to Blixen.[7]

But the fourth committee member Eyvind Johnson (who himself fifteen years later would accept the 1974 Nobel Prize in Literature) opposed a prize to Blixen arguing that Scandinavians were overrepresentated among the Nobel laureates in literature. Johnson instead proposed a prize to a representative of the "rich, modern Italian literature", arguing that the Italian literature had been neglected and such a decision "would everywhere be perceived as a testification of the Academy's vigilance and be appreciated all over the literary world". Salvatore Quasimodo was Johnson's first proposal, followed by Ignazio Silone and Alberto Moravia.[7]

Unconventionally, the members of the Swedish Academy did not follow the Nobel committees recommendation to award Blixen, but was convinced about Quasimodo's candidacy and surprisingly awarded him the prize.[7]

Reactions

Summarize

Perspective

The choice of Quasimodo was largely met with negative reactions. The Swedish newspaper Aftonbladet criticized the Swedish Academy for "rewarding mediocrity" and many Italian critics agreed.[8] Commentators have argued that there were other Italian poets such as Giuseppe Ungaretti and Eugenio Montale (awarded in 1975) who would have been more worthy of the prize.[7][9] Nonetheless, C.M. Bowra of the New York Times said upon the prize announcement that "The Swedish Academy has shown a wise judgment and a welcome courage in giving the Nobel Prize for Literature to the Italian poet, Salvatore Quasimodo."[10]

Retrospectively, the decision to deny Karen Blixen the prize in favour of Quasimodo was called "reverse provincialism" by a Danish commentator when the Nobel records were opened after fifty years in 2010.[11] The same year, Kjell Espmark of the Swedish Academy described the Academy's rejection of Blixen as a mistake, saying that Blixen would likely have been better accepted internationally than other Scandinavian Nobel laureates and that an opportunity to correct the underrepresention of female laureates was regrettably missed.[12]

In 1985, American culture critic James Gardner noted: "Even the Italians seem to feel that the bestowal upon Quasimodo of the 1959 Nobel Prize for Literature was vastly in excess of his artistic attainments. For not only was it disputed that he possessed that Olympian stature implicit in the conferring of this last dignity upon a living author, it was also unclear why he should have been preferred before his two fellow Hermeticists Eugenio Montale and Giuseppe Ungaretti, or a dozen other Italian poets who were felt to be not only more melodious and more profound, but also much more easily understood. One solution to this mystery, which in its way is as peculiar and intractable as many of his poems, might be Quasimodo’s role in the Resistance, which would have cleared him of any taint of fascism, and then his sympathies with the Left, which in poets is always construed as a positive virtue."[13]

Remove ads

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads