Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

2025 Samoan general election

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

General elections will be held in Samoa on 29 August 2025 to determine the composition of the 18th Parliament.[1] Initially expected to be held in 2026, Prime Minister Fiamē Naomi Mataʻafa called a snap election after parliament voted down the government budget on 27 May 2025.

The Faʻatuatua i le Atua Samoa ua Tasi (FAST) party came to power after the 2021 election and subsequent constitutional crisis, which ended the 23-year premiership of Tuilaʻepa Saʻilele Malielegaoi and the nearly four-decade governance of his Human Rights Protection Party (HRPP). In January 2025, Mata‘afa and four other cabinet ministers were expelled from FAST after she dismissed party chairman Laʻauli Leuatea Polataivao from cabinet following his refusal to resign after being charged with criminal offences. Mata‘afa and the expelled ministers initially rejected their expulsions and claimed they were still party members. FAST subsequently split, with Polataivao leading a faction of 20 MPs while Mata‘afa led a minority government. Mata‘afa survived two no-confidence motions, one on 25 February and another on 6 March. Shortly after the election was called, Mata‘afa and her cabinet confirmed their departure from FAST and established the Samoa Uniting Party (SUP).

Remove ads

Background

Summarize

Perspective

2021 general election

The previous election, held in 2021, resulted in a tie between the HRPP and FAST, with both parties winning 25 seats. One independent, Tuala Iosefo Ponifasio, won a seat and became kingmaker.[2] The HRPP had governed Samoa for almost four decades, and its leader, Tuila‘epa Sa‘ilele Malielegaoi, had been prime minister since 1998.[3][4] A major campaign issue was the passage of the controversial Land and Titles Bill by the HRPP government in 2020.[5][6] Then-HRPP MP Laʻauli Leuatea Polataivao was expelled from the party due to his opposition to the bill and founded the FAST party.[7][8] Several other HRPP MPs also defected in protest of the bill,[9] including Deputy Prime Minister Fiamē Naomi Mataʻafa, who was elected to lead FAST shortly before the election.[10][11] Weeks before the poll, the HRPP passed a law requiring MPs to contest a by-election if they change their affiliation in parliament, allegedly to prevent more MPs from defecting.[12]

2021 constitutional crisis

After the election, the HRPP and FAST negotiated with Ponifasio, seeking to win his support to form a government.[13] Ponifasio later joined FAST;[14] however, during the talks, a dispute arose over the fulfilment of the female quota. The Office of the Electoral Commission (OEC) declared the quota had not been met and appointed a sixth female member to parliament, Aliʻimalemanu Alofa Tuuau of the HRPP, resulting in a hung parliament.[15][16] Prime Minister Malielegaoi subsequently called a snap election,[17] while FAST challenged both decisions in court.[16][18] The Supreme Court overturned the fresh election call, Tuuau's appointment, and ordered parliament to convene within 45 days of the election in accordance with the constitution.[19] The O le Ao o le Malo, Tuimalealiʻifano Vaʻaletoʻa Sualauvi II, scheduled for parliament to convene on 24 May, the final day it could meet,[20] but later retracted the proclamation.[21] In response, the Supreme Court nullified the retraction. Malielegaoi refused to accept the results or cede power, plunging the country into a constitutional crisis.[22][23] FAST conducted an ad hoc swearing-in ceremony on 24 May outside parliament, which the HRPP refused to attend or recognise as legitimate.[24] On 23 July, the Court of Appeals ruled FAST to have been the legitimate government since 24 May, ending the crisis. The ruling confirmed Mataʻafa as Samoa's first female prime minister and ended Malielegaoi's almost 23-year tenure as head of government.[25]

During the constitutional crisis, several HRPP members resigned or were stripped of their seats by the Supreme Court due to electoral petitions alleging electoral malpractice such as bribery. In the November 2021 by-elections to fill the vacancies, FAST won five seats while the HRPP only held two.[26][27] FAST won all by-elections thereafter, and by September 2023, the party had attained a two-thirds majority in parliament, with 35 seats.[28]

2025 political crisis

On 3 January 2025, Agriculture and Fisheries Minister Laʻauli Leuatea Polataivao was charged with 10 criminal offences, including harassment and conspiracy to pervert the course of justice over a political smear campaign that attempted to pin an unresolved hit-and-run case on a senior politician.[29][30] Prime Minister Mataʻafa dismissed him from cabinet on 10 January after he refused to resign,[31] and sacked another three cabinet ministers, citing disloyalty.[32] On 15 January, the party removed Mataʻafa as FAST leader and expelled her, along with Deputy Prime Minister Tuala Iosefo Ponifasio and three other cabinet ministers from the party.[33] Mataʻafa and the ousted ministers denounced the expulsion as illegal and maintained they were still FAST members.[34] The party unanimously elected Polataivao as leader on 16 January, while Leota Laki Lamositele became deputy leader.[33] The FAST party split into two factions, with 15 MPs remaining loyal to Mataʻafa and the other 20 joining Polataivao. Mataʻafa continued as prime minister in a minority government.[35] Polataivao and his faction called on Mata‘afa to resign as prime minister but stated their opposition to a snap election.[36]

No-confidence motions

On 25 February, Mataʻafa survived a no-confidence motion filed by the HRPP, which Polataivao's faction voted against. The FAST leader opposed the motion, citing a need for parliament to focus on key legislation, including amendments to the Land and Titles Act. Polataivao, however, announced he would introduce a second motion if Mataʻafa did not resign before the end of the parliamentary sessions.[37] A week later, on 6 March, Mataʻafa defeated a second motion, which the HRPP voted against. The prime minister and her cabinet accused Speaker Papaliʻi Liʻo Taeu Masipau of lacking impartiality for approving another confidence vote only after a week. The HRPP initially negotiated with Polataivao's faction on moving a second motion but withdrew their support after the bloc refused to support a snap election.[38]

Budget defeat and snap election call

Polataivao's trial began on 26 May.[39] The following day, the government's budget was voted down by 34 to 16,[40] with the HRPP and Polataivao's faction voting against it.[41] Mataʻafa stated that by convention, a government's budget defeat reflects an issue of confidence in parliament[42] and, on 28 May, advised the O le Ao o le Malo to dissolve the Legislative Assembly and call a snap election,[43] bringing forward the polls originally expected for 2026.[44] Mataʻafa and her cabinet subsequently confirmed their resignations from FAST and founded the Samoa Uniting Party (SUP).[45]

Following the announcement, Attorney-General Suʻa Hellene Wallwork said that the government would seek a court ruling on how to resolve inconsistencies between the Electoral Act, which requires candidates to be nominated and electoral rolls to close six months before an election, and the constitutionally required election timeline of three months.[46] At the time of parliament's dissolution, the OEC was conducting a re-registration drive of the electoral rolls. As only around 50% of eligible voters had registered, Electoral Commissioner Toleafoa Tuiafelolo Stanley requested additional time to allow more citizens to register.[47] On 6 June, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutional three-month timeline and set the election for 29 August, denying the OEC's request.[1] The court also stated that the next government would need to address the inconsistencies between the Constitution and the Electoral Act.[48]

FAST challenged the dissolution in court, claiming it was unlawful and that the party had a parliamentary majority to govern.[49] Shortly after the announcement, the Legislative Assembly clerk, Satama Leatisa Tala, wrote to the O le Ao o le Malo, attempting to nominate a new government. Tala mentioned the number of MPs in each party, stating that FAST held a majority despite parliament having dissolved. Mata‘afa said Tala's report had no legal validity as it was based on the composition from the beginning of the parliamentary term.[50] The O le Ao o le Malo ultimately determined that Mata‘afa's government would retain control of the executive in a caretaker capacity until after the election, in keeping with convention.[51]

Remove ads

Electoral system

Summarize

Perspective

The 2025 election will see 51 members of parliament elected from single-member constituencies via the first-past-the-post voting system.[52] The 2013 Constitutional Amendment Act mandates that at least 10% of members of parliament are women. If this quota were unfulfilled following an election, parliament must establish up to six additional seats allocated to the unsuccessful female candidates who attained the highest percentage of votes.[53] To be eligible, candidates are required to hold a matai title, have reached the age of 21 and have resided in Samoa for at least three years before the nomination deadline. Individuals convicted of a crime in Samoa or any other country within the previous eight years and people with a mental illness were ineligible to stand as candidates. Civil servants were permitted to run as long as they resigned. Should civil servants fail to do so, the date of filing their candidacy is by law deemed to be the point when they relinquish their role.[54]

Voters

Universal suffrage came into effect in 1991, permitting all Samoan citizens aged 21 and older the right to vote.[55] Compulsory voting took effect at the 2021 general election.[56] Individuals who fail to cast a vote are required to pay a fine of 100 tālā. Eligible voters who do not register are liable to pay a 2000 tālā fine.[57] In April 2024, Lefau Harry Schuster, the minister responsible for the OEC, announced the commission would conduct a nationwide re-registration process, citing a need to upgrade the previous electronic enrollment system, which he said had become plagued with technical difficulties and could not accommodate new registrations. Schuster stated that Samoan citizens residing abroad who fail to register could be prosecuted upon returning to Samoa. He assured voters already enrolled were only required to undergo the biometric process. Samoan citizens overseas could register online but needed to travel to Samoa to complete the biometric stage.[58] A bill permitting citizens to cast votes outside the country was not voted on in Parliament before the dissolution, thus maintaining the requirement for voters overseas to return to Samoa to vote.[59] The electoral commissioner announced Samoans born overseas to parents who are Samoan citizens and resident abroad would be ineligible to participate in the election.[60] At the closure of voter registrations, 102,109 of the 117,225 eligible voters or 87%, were enrolled to vote. Final figures are expected to be released after the OEC scrutinises the electoral roll.[61]

Remove ads

Schedule

Summarize

Perspective

The O le Ao o le Malo formally dissolved the 17th Parliament on 3 June and issued the election writ a week later on 10 June.[62][63] The OEC released the final election timetable on 13 June. Voter enrollment closed on 4 July, while the candidate registration period commenced on 7 July and concluded on 12 July.[64] The campaign period began on 14 July and is set to end on 24 August. The OEC announced that campaigning outside of this period would be illegal.[44] Candidates have until 14 August to withdraw their candidacies if they intend to do so,[64] while early voting was scheduled for 27 August.[65] Per the Public Holiday Act, the Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Labour designated election day and the day before as public holidays, with the aim of maximising voter participation.[66]

Parties and candidates

Summarize

Perspective

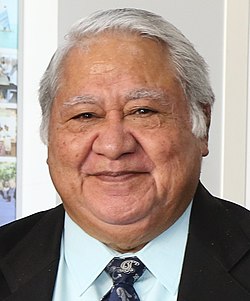

Six parties contested the elections,[67] including the Human Rights Protection Party, led by former Prime Minister Tuila‘epa Sa‘ilele Malielegaoi, the Fa‘atuatua i le Atua Samoa ua Tasi party, led by La‘auli Leautea Polataivao. In addition to Prime Minister Fiamē Naomi Mata‘afa's Samoa Uniting Party, three other newly founded parties were registered to contest the election:[57] the Samoa Democratic Republican Party (SDRP),[67] the Samoa Labour Party (SLP) and the Tumua ma Pule Reform Republican Party (TPRRP). Led by former Justice Minister Faʻaolesa Katopau Ainuʻu,[57] the SLP was established by former HRPP members, who were dissatisfied with the party's candidate selection process.[68] The TPRRP was led into the election by Molio‘o Pio Molioʻo, the husband of FAST member and former finance minister, Mulipola Anarosa Ale Molioʻo.[69]

By the nomination deadline, a record 191 candidates were registered to contest the election, while one had been rejected.[70] There were 24 female contestants, a slight increase from the 21 in the 2021 election.[67][71] Two Faʻafafine also ran in the election.[72] FAST fielded 61 candidates, the HRPP 52, while the SUP ran 26. Labour had six candidates, the SDRP and the TPRRP each fielded one and the other 44 contestants were independents.[67]

Remove ads

Campaign

Summarize

Perspective

Most parties contesting the election included platforms promising job creation, free public healthcare and infrastructure investment.[73] The official campaign period began on 14 July; however, reports surfaced of several candidates publishing campaign posters on social media beforehand. The OEC announced that campaigning outside of the official period, including the distribution of posters, was unlawful.[74] Several chiefs in Falelatai, the village of the O le Ao o le Malo,[75] located in the Falelatai and Samatau constituency, announced a ban on parties from campaigning in the village.[76] The village chiefs had also attempted to block any candidates from contesting the district, aside from HRPP members.[77] The HRPP had won the constituency in the two previous elections.[75] The electoral commissioner stated that the move was illegal.[76] Malielegaoi denied that the HRPP or the O le Ao o le Malo had any involvement with the chiefs' decision.[78]

During a FAST rally on Savaiʻi, Polataivao claimed Mata‘afa had suppressed evidence in the case of the murder of Caroline Sinavaiana-Gabbard. In response, Mata‘afa filed a defamation complaint and stated that Polataivao should avoid personal attacks and "stick to the issues". Police Commissioner Auapaʻau Logoitino Filipo said the FAST leader's allegation was similar to a claim made against the prime minister in March 2025, which a police investigation found was false.[79] Malielegaoi denounced Polataivao's claim and called for him to be arrested.[80]

Faʻatuatua i le Atua Samoa ua Tasi

The FAST party announced its campaign would significantly focus on economic revitalisation and social welfare.[73] The party launched its manifesto on 12 July in Savaiʻi, announcing free hospital care, a new hospital in Salelologa, an increase in village development funding, increased support for families, and a baby bonus. It also planned to raise the retirement age from 55 to 65, launch a $1.5 billion tālā carbon credit scheme and establish a national stock exchange.[81] FAST, furthermore, intended to revitalise Samoa Airways by investing $300 million tālā into the airline and raise the annual district grant from one to two million tālā for each district, which would total $110 million tālā of the yearly government budget.[82]

Human Rights Protection Party

The HRPP campaigned on providing economic support and proposed large-scale infrastructure projects. The party had the most policy proposals in its manifesto,[73] including a poverty alleviation strategy that would see families receive annual cash grants of $500 tālā for every family member. Malielegaoi claimed Samoa's economic situation had faltered during FAST's tenure in government and that the country used to be "looked up to" by other Pacific Island nations, but that the party had left Samoa in an "embarrassing" state.[83] The HRPP released its full manifesto on 20 June, having commenced campaigning earlier that month, with proposals to reduce taxes, hospital expansion and the construction of a bridge between Upolu and Savaiʻi.[84]

Samoa Uniting Party

The SUP launched its manifesto on 15 July. Mata‘afa stated that the party had risen "from the ashes of FAST".[85] The party pledged to fulfil FAST's uncompleted promises from the last election, including electoral reform, a disability allowance and pension increases. The SUP announced it would retain the district grant programme, with funds varying from one to two million tālā, depending on each district's requirements and size. The party also promised to reduce the value-added goods and services tax, remove the electricity tax, and provide a 20% tax refund to all citizens if it formed a government after the election. Free education from early childhood to the tertiary level and an increase in the retirement age to 60 were also included in the party's manifesto.[86] The SUP vowed to return village lands seized by the German colonial administration that had not been repatriated to customary landowners.[87]

Remove ads

Conduct

The OEC received reports alleging that some individuals had unlawfully completed online registrations on behalf of intending candidates.[88] Some campaign committees also reportedly arranged and financed transport for voters to registration centres. The OEC warned that such a practice was illegal.[89] On 26 June, Police Commissioner Filipo announced the creation of a special election crimes taskforce to deal with voter fraud, vote buying, and other electoral crimes.[90]

Remove ads

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads