Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Third Dynasty of Ur

Royal dynasty in Mesopotamia From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The Third Dynasty of Ur or Ur III was a Mesopotamian dynasty based in the city of Ur in the 21st century BC (middle chronology). For a short period they were the preeminent power in Mesopotamia and their realm is sometimes referred to by historians as the Neo-Sumerian Empire.

The Third Dynasty of Ur is commonly abbreviated as "Ur III" by historians studying the period. It is numbered in reference to previous "dynasties" of Ur according to the historical reconstruction of the Mesopotamian past written in the Sumerian King List, such as the First Dynasty of Ur (26–25th century BC), but it seems the once supposed Second Dynasty of Ur was never recorded.[1]

This kingdom was founded by Ur-Namma (c. 2112-2095 BC), who succeeded in reuniting southern Mesopotamia a few decades after the fall of the Empire of Akkad. His son and successor Shulgi (c. 2094-2047 BC) then firmly held the heart of the kingdom, a very prosperous agricultural and urban region, where a very advanced economic administration was established, based on the temple domains controlled by the royal power. Under his reign, military campaigns expanded further the influence of Ur, creating an "Empire." Shulgi's successors managed to maintain the empire for a quarter of a century. Then it gradually disintegrated, under the combined action of incursions of Amorite populations from the North and internal forces which restored their autonomy to several important cities and regions. The kingdom of Ur was destroyed around 2004 BC by an Elamite army.

In Mesopotamian history, this imperial experiment can be seen as a continuation of the Akkadian Empire, which preceded it by about two centuries and served as a model. The Third Dynasty of Ur, however, is of Sumerian, not Akkadian, identity. Because its kings, administrators, and scholars primarily used the Sumerian language and promoted literature in Sumerian, this period is sometimes called the "Neo-Sumerian period" or even a "Sumerian Renaissance" (which also includes the dynasty of Gudea of Lagash, which ended with the beginning of the reign of Ur III).

The Ur III period is also remarkable for the quantity of written documents that have come down to us, the vast majority of which are administrative in nature. They give us an impressive amount of informations relating to the functioning of the kingdom, and of certain aspects of its society and its economy. This abundance of documents and the analysis of the administrative practices of the time may have given the impression of a "bureaucratic" state. It is at least certain that this empire saw official institutions (temples and palaces) take on an unprecedented importance, rarely equaled subsequently in Mesopotamian history, and gave rise to original administrative experiments.

Remove ads

Sources

Summarize

Perspective

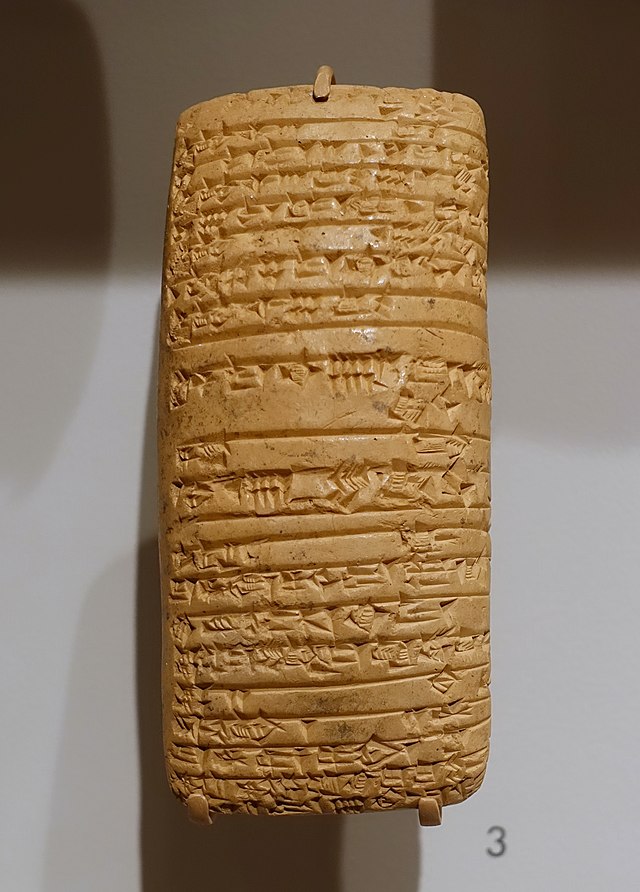

The main type of source documenting the Third Dynasty of Ur are administrative tablets, which number in the tens of thousands: an estimate of the number of unearthed tablets from this period is around 120,000, not including an undetermined number in the National Museum of Iraq. According to a 2016 inventory, "only" 64,500 of these have been the subject of a scientific publication with a copy/photograph and transliteration and/or translation. They come primarily from a handful of sites. The oldest known group of tablets was unearthed in 1894 at the site of Tello, ancient Girsu. The site's excavators came across a deposit of around thirty thousand tablets, clearly a governor's archive. But they did not clearly identify the place of origin, and some of the tablets were plundered by clandestine diggers. During these same years, regular and clandestine excavations of Nippur uncovered other tablets from the period, in smaller quantities (around 3,600). Then in 1909 and 1911, clandestine diggers discovered other deposits of tablets from the period, first at the site of Tell Jokha, ancient Umma (about 30,000 tablets) from the archive of the local governor, then at Drehem, ancient Puzrish-Dagan (about 15,000 tablets). Then the regular excavations of Ur brought to light more than 4,000 tablets from the period. In the 1990s-2000s, two other important archives were plundered during illegal excavations, on sites whose exact location is uncertain, but whose ancient name is known: Garshana near Umma (more than 1,500 tablets), and Irisaĝrig near Nippur (about a thousand texts).[2][3][4]

The vast majority of these are administrative documents from the archives of governors or temples, and date from the reigns of Shulgi (the last decade), Amar-Sin, Shu-Sin, and the very beginning of Ibbi-Sin, a period of approximately forty years. They generally take the form of small tablets recording the movement of goods, for example, 'bills' or receipts in the form of square cushions. But there are also more elaborate and larger management documents, often rectangular in shape, such as inventories, summary balance sheets, personnel management or planning documents, including cadastral registers and lists of workers. Non-administrative types of documents, found in lesser quantities, include: trial records, contracts (of lease, sale, loan), letters.[5]

The political history of the Third Dynasty of Ur is reconstructed primarily through the year names of the kings, which are known in full from the reign of Shulgi onward. Indeed, during this period, years were named according to events deemed significant by royal power (often military or religious). For example, the sixth year of Shu-Sin's reign is titled "Year Shu-Sin the king of Ur erected a magnificent stele for Enlil and Ninlil," and the seventh "Year Shu-Sin, the king of Ur, king of the four quarters, destroyed the land of Zabshali."[6] The chosen event had already taken place, during the previous year: thus, the capture of Zabshali took place in the sixth year of Shu-Sin's reign and, because of its importance, it was elected to name the following year. Since they are chosen by the royal authorities, year names give an "official" version of the history of the dynasty. They are used in the dating formula of administrative documents, and are also known from summary lists dated from later periods.[7][8]

Royal inscriptions are also known from this period.[9] These are mostly short inscriptions commemorating the founding or rebuilding of temples, but some from Ur-Namma's reign are more detailed about historical events. Hymns dedicated to kings of Ur provide additional information on the political and religious life of the period, and especially on royal ideology. This is a kind of "court literature" sponsored by the kings of Ur and known from copies dated to the first centuries of the 2nd millennium BC. But their reliability for reconstructing the political history is debated.[10]

Historiographical texts were written after the fall of the kingdom, such as letters presenting themselves as correspondence between kings of Ur and their administrators.[11] It is also debated to what extent they provide reliable information.[12]

Non-written sources are generally less well represented. The known material remains from the period are limited, although several large excavated monuments date from the Ur III period, particularly the imposing ziggurats of Ur, Nippur, Uruk, and Eridu, although the excavated levels are later. The repertoire of images is also less studied, the period having yielded few sculptures in comparison with the periods of the Akkadian Empire and the second dynasty of Lagash which preceded it. The cylinder-seals nevertheless provides appreciable information about the ideology of the imperial elite.[13]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

In the middle of the 22nd century, the Akkadian Empire was destroyed in circumstances that are not well known. The Gutians seem to be the main actors in this event, but we also note that Lower Mesopotamia broke up into several kingdoms that were formed around certain cities, notably Uruk and Lagash (whose most important king of this time was Gudea). A powerful kingdom was also created in Elam (southwestern Iran) by the king Puzur-Inshushinak. Around 2120 or 2055, King Utu-hegal of Uruk defeated Tirigan, the Guti king. He then exercised his sovereignty over southern Mesopotamia, but his reign was short-lived. After about eight years of reign, he was dethroned by notables of the court, headed by Ur-Namma, the governor of Ur (Mesopotamia), who was probably his own brother. Mesopotamian tradition recognized him as the founder of the third dynasty of Ur.[14][15]

Absolute datation of this period remains uncertain:[16] according to the mainstream Middle Chronology, usually used in the scientific publications, it lasted from 2112/0 to 2004/3 BC; according to the Low Chronology from 2048 to 1940 BC, and according to the Ultra Low Chronology from 2048 to 1911 BC.[17]

Ur-Namma

Upon his enthronement, Ur-Namma (formerly Ur-Nammu; c. 2112-2095 according to Middle Chronology) asserted his dominance over the territory previously ruled by Utu-hegal, centered on Uruk and Ur, and then extended his possessions throughout Lower Mesopotamia. He took the title of "King of Sumer and Akkad," symbolizing the unification of the city-states of Lower Mesopotamia, as had the kings of the Akkad before him. His domination in the northeast direction towards Diyala probably involved a victory over the Elamite troops of Puzur-Inshushinak, maybe with the help of Gudea of Lagash. Ur-Namma subsequently reorganized the dominated territories: restoration of the large cities and their sanctuaries, irrigation canals, and probably also an administrative reorganization, while his law "code" symbolizes his desire to show himself as a just king. He died on the battlefield on the eastern highland, after about 18 years of reign.[18][19][20][21][22]

Shulgi

Ur-Namma was succeeded by his son Shulgi, whose long reign (about half the duration of the dynasty) would organize and expand the power of Ur (c. 2094-2047). His father had probably laid the foundations for the organization of the kingdom, but he had to consolidate them and eventually create an 'Empire' following the model of the kings of Akkad. Of the first twenty years of this reign, only cultic activities are known, particularly in Ur and Nippur. The following 18 years place this king among the most brilliant in Mesopotamian history. Shulgi expanded his kingdom following several conquests towards the north and especially towards the northeast: his military campaigns resulted in victories in the region of the Upper Tigris River and the western Zagros (Arbela, Simurrum, Lullubum, Kimash, etc.), and Elam (Anshan). Marriage alliances were arranged with kingdoms of the Iranian plateau, including the powerful Marhashi, to find peaceful solutions to conflicts. The conquered regions were established as buffer provinces against the kingdoms that remained independent. A wall was built in the north of Akkad to face the incursions of the populations of the northwest, the Martu/Amorites. Numerous roads and canals were built. Shulgi also carried out numerous reforms that profoundly reorganized the central provinces. Some of these may have been initiated by his father, as it is sometimes difficult to disentangle the work of one from that of the other. This particularly concerns the taxation system, the organization of temple estates, the training of scribes and writing, the royal calendar, the construction of an important administrative center at Puzrish-Dagan. This resulted in a "bureaucratization" of the administration, explaining the documentary inflation that then took place. Shulgi's reign also saw the king being deified and the writing of a whole literature glorifying him. Several of his sons and daughters were placed at the head of major sanctuaries. Shulgi died after 48 years of a well-accomplished reign. The causes of his death are as unclear as those of his father, and it is possible that his last years were troubled.[23][24][25][26][27]

Amar-Sin, Shu-Sin, and Ibbi-Sin

Amar-Sin (c. 2046-2038) succeeded his father Shulgi, perhaps under turbulent circumstances (he doesn't seem to be the official heir to the throne), and reigned for nine years. His troops fought several times in the northern and eastern peripheries (Arbela, Kimash, Huhnur, etc.) where the domination of the kingdom of Ur had to be regularly asserted, while diplomatic relations with the kings of the Iranian plateau continued. The administrative system established by his predecessor still functioned well, as evidenced by the very abundant documentation dated to his reign. This reign can overall be seen as a consolidation of the achievements of the previous one. But from his seventh year of reign he replaced several important governors from prominent families, which could indicate a context of political tensions.[28][29][30][31][32]

Shu-Sin (c. 2037-2029), brother of the previous king, also reigned for nine years. He reinstated members of families ousted by his predecessor as governors, which is another indication of the tensions running through the top of the state. He, in turn, had to assert his authority in the northern and eastern peripheries (Shimanum, Zabshali, Shimashki). The tribute collected from these regions seems to arrive less regularly, a sign of a weakening of the King of Ur's influence. The most threatening danger came from the northwest, due to the incursions of Amorite groups. To counter this, Shu-Sîn reinforced the defensive system established by Shulgi by building a new wall. During the latter part of the reign, much of the power appears to have been in the hands of Chancellor Aradmu.[33][29][34][35][36]

Ibbi-Sin (c. 2028-2004), probably the son of the previous one, reigned for twenty-four years during which the kingdom disintegrated. The archives of the major administrative centers of the central regions dried up from the beginning of his reign (after the third year). Several military campaigns were conducted against the political entities located on the eastern margins of the kingdom (Anshan, Huhnur, Susa) which had taken their autonomy, but they were few in number and ceased after his fourteenth year of reign. Subsequently, the provinces close to the center also became independent: this is well known for Eshnunna and especially Isin under the leadership of Ishbi-Erra, a renegade governor. The incursions of the Amorite tribes are increasingly violent, while a situation of food shortage breaks out.[37][29][38][39][40]

The Fall of Ur

The exact course of the fall of Ur is poorly understood. It is reconstructed primarily from later sources, the reliability of which is unclear, notably the apocryphal letters which provide information on the conditions of the secession of Ishbi-Erra from Isin, which took place against a backdrop of subsistence crises and revolts. Even so, Ibbi-Sin managed to stay in power in Ur for about 20 years, controlling only a small portion of the empire he inherited. The fatal blow seems to have been dealt to Ur around 2004/2000 by an external intervention, that of a coalition of Elamite troops, the texts designating people from Anshan and Shimashki, or more broadly from Elam.[41][42]

Several causes have been put forward to explain the fall of the kingdom or Ur, notably structural weaknesses of the kingdom. The centralized and highly complex bureaucratic organization of the empire seem to have been difficult to maintain over time, especially when more troubled times arose. Provincial governors were only well-controlled when the sovereign's power was strong, and were able to assume their autonomy as soon as it weakened, starting with those on the periphery. Moreover, relations with neighboring people were never pacified despite numerous attempts (using military force, diplomacy or inclusion of mercenary troops), notably with the Elamite kingdoms and the Martu/Amorite tribe.[43][44][45] Climatic factors may also be in cause, a global warming which may have led to food shortages in the kingdom's final years.[46]

Remove ads

Government

Summarize

Perspective

A patrimonial state

The Ur III state followed a patrimonial system. The state was organized into a hierarchical pyramid of households with the royal household at the top. As described by Steinkeller it was a network of households linked together by mutual rights and obligations. All resources of the state were exclusively owned by the king and his extended family. All lower households were considered dependents of higher households and, ultimately, of the king. Inferior households contributed corvee labour to the royal household and received economic support, land, and protection in return.[47][48][49] As explained by J.-P. Grégoire, the king of Ur "manages the empire as his personal household. Power and authority are highly personalized, so that the public sphere is difficult to separate from the private sphere. The state is identified with the palace, the palace administration is confused with the government. The sovereign's family plays a prominent role in public life and in state affairs."[50]

Households (e2 "house" in Sumerian; similar to Ancient Greek oikos) are very diverse: from the basic (nuclear) family unit of commoners, to the estates of wealthy members of the local elite, to the larger domains of the gods (temples), members of the royal family, and the king (the crown).[51] The management of large institutions relies on the household unit, and this at all levels of the economy, for example with the family of Ur-Meme in the management of the temple of Inanna in Nippur and also the government of the province,[52] or among the foresters of Umma,[53] etc., where people work as a family and succeed each other from father to son. Positions in the administration or institutional fields would then be “patrimonialized” by certain families if they held them for a long period.[54]

The documentation suggests that most land belonged to temples and royalty, but it is possible that significant parts of the provinces were in the hands of less important, non-institutional houses. The connections between all these houses and the unifying role of the king's household make it difficult to distinguish between the "public" and "private" interests and activities of individuals. They could combine work for a temple, for the king, and also conduct more personal affairs.[51]

The king and his entourage

The dynasty of Ur was a hereditary monarchy that followed the Mesopotamian model.[55] The king (in Sumerian lugal "great/big man") is the head of the administration and the army, he appoints high officials and dispenses justice.[55] According to the official ideology of power, he owed his power to divine support, primarily that of the great god Enlil residing in Nippur. Ur-Namma called himself simply "king of Ur" at the beginning of his reign, before taking the title of "king of Sumer and Akkad" once he had extended his domination to all of Lower Mesopotamia.[56] His son Shulgi followed the example of Naram-Sin of Akkad by adding the title of "King of the four corners (of the world)" (that is, of the whole known world).[57] Hymns to his glory were written, highlighting his qualities and making him an ideal sovereign. He attained a rank that raised him above men to the status of divinity: the determinative of divinity was placed before his name, he received a cult and temples were dedicated to him. His successors followed his example.[58][59]

The kings of Ur had several palaces (in Sumerian e2-gal "great/big house") in his kingdom, which did not include a "capital" as such. They had three main centers of power, in three venerable Sumerian cities: Ur, the seat of the dynasty; Nippur, the principal holy city of Lower Mesopotamia; and Uruk, perhaps the original city of the dynasty, which was the least important of the three centers. Shulgi and his successors seem to have resided primarily in the province of Nippur (including in the royal palaces of Tummal and Puzrish-Dagan); they traveled regularly to the other two cities, at least to perform major religious celebrations.[60] Sources, such as a hymn to Shulgi, indicate that the kings of this dynasty were crowned in these three major cities. On this occasion, they received the symbols of royalty (a crown, a scepter, a throne).[61][62] The kings moved frequently, meaning they did not reside in the same place all year round. They traveled in the company of a group of people who could be referred to as their "court," which, in the narrow sense, included members of their family, courtiers, and their household, i.e., people who were in contact with them (without necessarily residing in a palace). In a broad sense, the court can be understood as all the people who are likely to be in contact with the king, but are not necessarily physically in his presence.[63]

The kings of Ur had a principal wife, who bore the title of "Queen" (nin), although this allowed for exceptions, since Shu-Sin seems to have reserved this title for his mother Abi-simti; they were clearly descended from prestigious foreign royal lines. Then came a group of secondary wives, lukur, a term originally designating priestesses considered the wives of a god, which probably had to do with the deification of the kings of Ur. There were important distinctions within this category, which included many women. They were housed in the various royal palaces, in harems from which they were probably few able to leave, where they had an administration at their service. Their political role was limited or even nonexistent, but on the other hand they played an active role in the cult, first and foremost the queen. A wife (or concubine) of Shulgi, Shulgi-simti, whose archives were unearthed in Drehem, thus initiated a foundation that provided animals to be sacrificed during various rituals.[64]

The rest of the members of the royal family also supported the king in running the kingdom.[65][66] The princes held administrative, military, or religious responsibilities. Princesses also played an important role, particularly in the cult: several kings' daughters became high priestesses of the god Nanna in Ur, as in the time of the kings of Akkad. Others were married to foreign kings or members of the kingdom's prominent families. There was thus a true patrimonialization of the kingdom, since the highest positions were reserved for members of the royal family or those related by blood to it. The Garshana archive thus documents the activities of an estate assigned to Shu-Kabta, a general and physician, and his wife Simat-Ishtaran, a royal princess. In return, these alliances tied the elites to the royal household, consolidating the influence of the kings.[67][68][69]

After the king, the second figure in the central administration is the sukkalmah, which can be translated as "grand vizier" or "Prime Minister." He has very broad and ill-defined power, both in the civil and military domains, and can also be a provincial governor. This is the case of Arad-Nanna/Aradmu, the very influential Prime Minister of Shu-Sîn and governor of the rich province of Girsu as well as several border marches. The Prime Minister directs the sukkal, traveling officials who also have various responsibilities and are dispatched throughout the kingdom. The king thus has a network of loyal controllers who allow him to know everything that is happening in his country. Other important figures in the central administration are known, such as the chief cupbearer (zabar-dab5) who seems to deal with religious matters.[70][71]

Provincial administration

One of the major challenges of Ur-Namma's reign and the first part of Shulgi's reign was the establishment of an administrative system uniting the ancient kingdoms that divided Lower Mesopotamia into a coherent whole. Rather than viewing the new entity as a territorial state in the modern sense of the term, it has been proposed to see it as a kind of archipelago, the "islands" of which were the urban centers, the seats of households governing the domains of institutions and individuals, and connected to each other by roads and canals. The task of the kings was then to better connect these "islands" with each other, and above all to firmly link and attach them to their own household, which resulted in increasingly tight state control over the domains and therefore over the economy.[72]

The heart of the empire, the "country" (kalam), is divided into about twenty provinces, the most important of which are ruled by the principal cities of the countries of Sumer and Akkad, in particular those of Ur, Uruk, Nippur, Umma and Girsu. Following the principle established in the Akkadian period, the provinces were headed by a civil governor (ensi2) appointed by the king, responsible in particular for the supervision of the population, tax collection, especially for the bala redistribution system (see below), and justice. They often came from the leading families of the province and passed their positions down through inheritance, constituting locally influential dynasties. Unlike in the Akkadian period, the local elites were loyal to the government since there were no large-scale revolts.[73][74] Temples domains were an important unit of production and labor organization, especially in the south of the kingdom. In the province of Girsu, there were about fifteen such temples. They were managed by chief administrators (šabra, sanga), supervised by the governors.[75] Each province also had a military governor (šagina), who led the provincial garrisons and supervised royal land, independently of the governors. They were chosen from among the king's close associates and regularly changed assignments, which reinforced their dependence on the monarch and deprived them of a local anchor.[73][74]

Beyond the provinces of Lower Mesopotamia that constituted the heart of the empire, the territories subjugated by the armies of Ur were transformed into a "peripheral zone" (ma-da). This was a defensive and tribute-collecting zone with fluctuating boundaries. These regions extended along the Tigris, perhaps as far as Ashur or even Nineveh, and east of this river, on the foothills of the Zagros, from Urbilum to Pashime and Susa.[76][77] This was a frontier zone similar to the Roman limes, comprising military colonies mixing Lower Mesopotamian populations, mainly soldiers, and indigenous peoples. They were ruled by military governors (šagina) and have agricultural land. These regions did not contribute to the bala redistribution system that normally concerned the central provinces, but were subject to a contribution called gun2 ma-da, "periphery tax", paid by the delivery of livestock.[77]

Unifiying policies

Another problems faced by the first kings of the dynasty was the fact that each of the cities in their kingdom had long since developed its own practices regarding metrology, calendar, writing, and scribal training. An effort at harmonization is therefore being attempted in these different areas.[78]

A standardization of weights and measures is generally attributed to Shulgi, but it may have been the work of his father, and in any case, it is partly based on a similar reform from the Akkadian period. This system is based on a measure of capacity, the royal gur (approximately 300 liters), and standardized conversions between the main metrological systems (units of volume and weight).

The desire to harmonize standards is also evident in the establishment of a royal calendar (historians refer to it as a Reichskalender), based on the one in use at Ur, and employed elsewhere (notably at Puzrish-Dagan) by the royal administration. This calendar is not stabilized, since it underwent several modifications. It is not a unification, since the local calendars remain in use for local affairs.[79]

The reform of the practices and training of scribes was also undertaken by Shulgi. It is based on institutions called "Houses of Tablets" (e2-dubba), a term generally designating places of training for scribes, but which here have an official aspect and could be considered as a kind of "academies." The scribes trained were responsible for the flourishing of Sumerian literature during the Ur III period, particularly official texts glorifying the ruling dynasty.[80]

The strengthening of the cohesion of the empire also involved expanding and making the communications network more reliable, based on roads and waterways. Administrative tablets document a network of roads and stopover lodges. They were traveled by messengers and officials, identified on tablets mentioning their mission and the compensation they received on occasion. These road works were accompanied during the period by various works on the canal network, since river navigation is important in southern Mesopotamia; they were also used for irrigating fields.[81][82]

Law and justice

Dozens of sources provide information on the legal organization of the Kingdom of Ur, which was an essential element in its proper functioning and legitimacy. The ancient Mesopotamians had indeed paid great attention to the ideal of justice since very early times and had developed an empirical legal system. This is particularly evident in one of the most important legal documents of the period, the Code of Ur-Nammu,[83][84] known from fragmentary late copies that preserve only part of its prologue and nearly 40 court sentences, the so-called "laws" that were probably not intended to be applied rigorously. This text is rather a collection of exemplary or scholarly nature and a glorification text whose function is to highlight the figure of the just king. It is the earliest of its genre, paving the way for others down to the Code of Hammurabi.[85] The bulk of the legal sources consist of practical documents: approximately 250 trial reports written after the cases were concluded. They cover a variety of topics: inheritance, marriages, business, crimes and misdemeanors, slave-related issues, etc.[86]

The judicial structures of the Kingdom of Ur were based primarily on the king, the supreme judge, but he did not often exercise this function in person. He delegates this task to his administrators, primarily the provincial governors, but also to professional judges (di-kud) who sit collegially. They may be assisted by a civil servant, the maškim (which is never a permanent position), who investigates certain cases (e.g. taking depositions) and, above all, records them to potentially serve a witness later.[87] The judicial authorities can be seized by anyone, man or woman, free or slave. They rule after studying evidence (testimonies, written documents), or require oaths to be sworn by the gods.[88] The question of whether there is a centralization of judicial institutions is debated: it seems that the central power must, as in other areas, deal with local judicial authorities, which have a margin of autonomy and can limit its influence.[89]

Remove ads

Economy

Summarize

Perspective

Labor management

The administration of the Ur III institutions operates primarily around a mass of dependents (guruš for men, geme2 for women) organized into "troops" (erin2, a term common to army vocabulary). Women from working-class categories are an essential component of the workforce of institutions, not being confined to working in the domestic sphere, far from it.[90] These dependents worked full-time directly for the institution and can be mobilized for all sorts of work in addition to their main task if necessary: weavers, for example, find themselves working in the fields during harvest time, grinding flour, or even hauling boats on the canals. They are paid in maintenance rations, mainly in barley grain and wool, but sometimes also in oil, dates, beer, etc. These are personnel entirely dependent on the institution. Other people not dependent on the institutions can work there for a few months a year for wages similar to rations; the existence of a "labor market" is debated, some believing that the period is rather characterized by a shortage of labor. The administrators are remunerated by the allocation of subsistence fields which they have exploited in the same way as the temple lands[91][92] As for slaves (arad2), well documented in legal sources, they do not seem to play an important role in the economy. They were generally prisoners of war assigned to an estate or people who had lost their freedom as a result of indebtedness.[93]

The many scribes who were at the various levels of the administration of the great temples produced an impressive mass of management and accounting documentation. In productive activities (agriculture, livestock and crafts), objectives were assigned to personnel who received the means of production often taken from other productions of the institution (fields, seeds, herds, agricultural and craft tools, raw materials, etc.) and were assigned their task to carry out with what they had to pay. Once the production operation was completed, there was a new control and the product could be directed towards another production activity where it would be used or towards an end consumer, notably within the framework of the internal redistribution within the organization (maintenance rations, salaries, religious offerings). Surpluses could be entrusted to merchants who sold them on the market or lent against interest. This involves the management of large and numerous warehouses, the control of the entry and exit of products passing through them, a form of registration of arable land, the management of irrigation networks, etc. The various offices of the institutions must carry out an annual accounting by drawing up a balance sheet, with administrators being held responsible in the event of unjustified losses or unmet objectives. This then makes it possible to evaluate future production and plan it to set production objectives, and so on.[94] Nevertheless, it is believed that this inflation of control and administrative demands must have caused management problems that weakened the Ur III state. It seems that very often the administration asked its dependents to produce more than they could.[95]

- Small tablet recording a movement of livestock on behalf of an institution. Umma, c. 2060 BC. Museum of Fine Arts of Lyon.

- Large inventory tablet of an institution: annual report of basketwork, reign of Amar-Sin. Louvre Museum.

- Large inventory tablet and some of the small daily management tablets from which it centralizes information, on the movement of animals. Puzrish-Dagan, reign of Amar-Sin. Museum of the Oriental Institute of Chicago.

- Reverse of a tablet of estimates for harrowing and plowing a field with the workers' wages, authentified by seal impressions of an administrative scribe ("presentation" scene), Umma, reign of Shu-Sin. Musée du Louvre.

- Plan of a real estate of the city of Umma, with indications of the surfaces of the parts. Louvre Museum.

- Clay bulla that sealed the bonds of a bundle, with the impression of the seal of Naram-ili, an official during the reign of Shulgi. Louvre Museum.

Agricultural lands

The organization of the agricultural domains of the temples is based on various units of cereal fields (a-ša3), well known for those of Girsu and Umma. This is a tripartite division of land (already attested in earlier periods): domain lands (gan2-gud, "ox lands"), exploited directly under the direction of team leaders (engar) who have under their orders teams of ploughmen paid in maintenance rations with their plough animals, are intended to meet the current needs of the temple (food and remuneration of the staff, cult offerings), and apparently constitute the majority of the domains of these institutions; subsistence fields (gan2-šukura), granted to members of the temple administration as compensation for their service, while the king grants land to the dignitaries of his kingdom, also in exchange for their services; leasehold fields (gan2-apin-la) rented to farmers who must pay a fee in barley and money corresponding to about 1/3 of the harvest.[96][97][98] These domains were supervised by the civil governors. Other fields were part of the royal sector supervised by the military governors, and allocated to recently settled royal dependent workers (erin2), in exchange for corvée labor. In the Umma province, temple estates made up only 7% of the province's area (but more than 13,000 hectares), being considerably smaller than the royal sector; royal settlers made up two-thirds of the province's population.[99] This situation might be the result of a reform carried out by Shulgi, which included land confiscations in order to reduce the power of the temples.[100]

Workshops

The best-documented craft activities are those taking place in state workshops. They are managed by officials responsible for their supply of raw materials, the organization of tasks and the definition of production objectives, the control, storage and distribution of finished products, as well as the recruitment and remuneration of craftsmen who are supervised on a daily basis by foremen. These offices can take charge of several groups of workshops dealing with various activities: a Girsu office thus brings together sculptors, goldsmiths, stonemasons, carpenters, blacksmiths, tanners, upholsterers and basket makers. The craftsmen are divided according to the material they work. Textiles are by far the most important activity of the institutional workshops, as evidenced by the 6,000 workers in the province of Girsu managed by a single office (though probably disseminated in several workshops). These are mostly women and also children, working primarily with wool (linen is also a common fabric). The working days, the type of fabric produced, and the time taken to make them are recorded with great precision. All these workers are paid by rations.[101]

A redistributive economy

The economy of the Ur III period is fundamentally redistributive. The means of production are controlled by the representatives of royal power in the provinces, and ultimately by the king, even if a substantial part of them is nominally in the hands of the gods (through the temples). The workers in the institutions are dependent laborers, free or not, who work in the fields, in workshops, and on public works (canals, walls, roads, temples). In exchange, the institution provides them with rations (mainly grain/bread, beer, wool). The state receives the majority of agricultural production and uses the surpluses to procure other goods. For this, it relies on merchants (dam-gar), who serve as intermediaries and tax collectors, and are therefore important in the redistributive system.[102]

The centralized aspect of the Ur III economic system is best seen in the bala ("rotation") system created during the reign of Shulgi. It is a system of taxation and redistribution involving the central provinces, each of which must take turns providing products to the central state. Most provinces contribute for a period of one month, but the larger and richer provinces of Girsu and Umma contribute for two or three months of the year. The products seem to be required according to the specialties of certain regions: Girsu thus provides a large quantity of grain, Umma reeds, wood, and leather. The products provided are used primarily for the expenses of the royal house and the sanctuaries, and can be reallocated to other provinces, establishing a system of circulation of products across the kingdom. Other times, provinces send workers to others under these same obligations. This system also serves to capture and redistribute the loot taken during military campaigns. It was limited in time since it was in place from the reign of Shulgi until the beginning of that of Ibbi-Sin. For a time, it ensured a process of large-scale redistribution of wealth in the kingdom, a testament to the kings of Ur's desire for advanced economic organization, rediverting the agricultural surpluses to the crown.[103][104][105][100]

The archives of Puzrish-Dagan occupy a central place in discussions on the organization of the levies and redistribution of wealth in the kingdom of Ur at its height. This city, located near Nippur, became at the end of the reign of Shulgi a major administrative center, and this situation lasted until the beginning of the reign of Ibbi-Sin, i.e. for about 26 years. The bulk of the tablets from this site document the activity of an organization, subdivided into several offices, with "branches" in other cities, headed by a central office, which organized the movement of livestock on a large scale, and could thus manage the transfer of some 70,000 sheep during a single year. These animals are supplied by the various existing collection systems, including donations from important figures. They are then redirected to various eminent figures, or sanctuaries for sacrifice, or to other provinces, or slaughtered on site for food and their secondary products, notably leather, worked in workshops in Puzrish-Dagan. It has also been pointed out that the beneficiaries of the deliveries are often members of the royal family or the elite, or foreign dignitaries and ambassadors.[106][107]

To operate this system, the state relied on groups of servants, who could be estate administrators, soldiers, messengers, or merchants. The kingdom's elites were, after the royal family and the gods, the main beneficiaries of the kingdom's system of wealth redistribution, while also being important contributors, thus linking them to royal power and the management of the empire and its resources. This would ultimately confirm the personal and patrimonial aspect of the exercise of power by the kings of Ur, rather than the existence of a bureaucratic system based on centralized institutions.[108]

The administrative documentation should not, therefore, be overinterpreted. The image of a well-organized empire firmly ruled by a central power through bureaucratic institutions, often associated with the Ur III empire, is undoubtedly false, especially if we take into account the rather limited time span (around thirty years) during which most of the administrative documentation was produced, and the fact that the majority of the tablets come from a limited number of sites (Girsu and Umma provide about half), located in the heart of the Sumerian country (and very few from the periphery).[109] The quantity of administrative documentation probably reflects the aspirations of the authorities for centralized control more than the reality of such control.[110]

Remove ads

Relations with the wider world

Summarize

Perspective

Foreign policy

From the reign of Shulgi, a peripheral zone was gradually established under the control of the kingdom of Ur, to the north and east of its core, where its presence was ensured by garrisons. These regions were subject to the payment of a tribute. Indeed, the interest in dominating these areas was largely economic, since they provided tribute and booty and were crisscrossed by important trade routes. In the northwest and east, and more generally beyond the peripheral zone, diplomacy was the order of the day: alliances were concluded with the most important kingdoms, consolidated several times by matrimonial alliances. P. Steinkeller even sees this as a carefully considered "Grand Strategy":[111]

While abandoning the idea of large-scale foreign conquests, and setting instead for a compact, highly centralized native state with a ribbon of defensive periphery, the Ur III kings still aimed at political and economic domination of much of the territories previously impacted by the Sargonic expansion. Rather than by wars, those objectives were achieved by diplomacy and mutually benefical economic exchanges with other powers. The result was an exquisitely designed self-limiting - and largely defensive - imperial strategy.

The aims of the military campaigns of the Ur III kingdom were undoubtedly diverse: they certainly served to extend the influence of the kingdom, but also to keep potential threats at bay, to control trade routes and (above all?) to obtain tribute and booty. These include livestock, the redistribution of which among the elite then takes on great importance in administrative sources. The booty raised during military campaigns may have been very significant during the height of the empire, and the fact that the eastern conquests were carried out towards grazing regions and active trade routes reflect a desire to access resources. Taking into consideration the heavy expenses it generates, war is an essential factor in the economy of the kingdom.[112][113][114][115] The great walls built during the reigns of Shulgi and Shu-Sin in northern Lower Mesopotamia therefore had a defensive purpose (against the Amorite threat?), and were probably also intended to consolidate the empire's borders, in order to strengthen the protection of its heartland. Moreover, they can be seen as an attempt to establish a boundary between the civilized world and the "wild lands", which were difficult to control.[116]

The organization of the army of the Third Dynasty of Ur is poorly understood. The core of the army seems to have been made up of professional troops, who were mobilized for military campaigns, but also for escort missions and more generally to ensure the security (guard and police missions) of the provinces and the peripheries. Garrisons were distributed throughout the empire, under the direction of a hierarchical command, whose most important figures were the "captain" (nu-banda3), commanding a few hundred men, and the military governor or "general" (šagina/šakkanakkum). The latter were often princes and members of the king's entourage.[117]

The foreign policy of the Third Dynasty of Ur seems to have relied heavily on diplomacy to ensure good relations with various important foreign rulers (considered its perspective as mere ensí "governors," with only the King of Ur being a lugal "king"[118]) located on its fringes, particularly in Syria and the Elamite region (southwestern Iran), which were on important trade routes. This represented a significant change from the Akkadian Empire, which had made these regions the targets of several of its military campaigns.[119][120] Marriage alliances are the most obvious indications of this desire (and extend similar alliances with the elites of the kingdom of Ur).[121]

Regular diplomatic relations took place through messenger-ambassadors (there were no permanent embassies at that time) coming from foreign kingdoms and received at the royal court as is attested by texts from Puzrish-Dagan. These texts mention the food and drinks distributed to them when they resided in Lower Mesopotamia (but it is not known if this was at the palace), where they were taken care of by local officials (sukkal) who could sometimes act as interpreters. When they left, they received what was necessary for their return journey as well as gifts intended for their master according to the diplomatic customs of the time. The king of Ur had his own messenger-ambassadors, supervised by the Prime Minister who managed a sort of diplomatic service in addition to his other duties.[122]

The East and Elam

The lands to the east of Mesopotamia were mountainous and designated in Sumerian by the word "high," "elevated" (nim). The main cultural entity of southwestern Iran is Elam, a country divided into several regions, each with its own specific characteristics, and politically divided at this time, after the defeat of its king Puzur-Inshushinak against Ur-Namma. The traditional contact zones between Lower Mesopotamia and the Iranian plateau, controlled by the Kingdom of Ur, are the Diyala Valley, where garrisons were established, and the Susiana Plain, around the city of Susa, where texts from the period have been unearthed. The latter provided access to important trade routes and the resources of the Iranian plateau and Central Asia (Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex). The kings of Ur had to deal with political entities further west, notably Anshan (Tell-e Malyan in Fars) and Marhashi (in eastern Iran). Political marriages were contracted in order to establish peaceful relations, but this was not successful as wars broke out regularly. A new political power, the Shimashki dynasty, took power in Anshan and Elam and finally dealt the final blow to the Third Dynasty of Ur.[123][124]

The West and the Amorites

The Ur III dynasty's main political partner in the West was the kingdom of Mari, located on the Euphrates River in present-day Syria (near the Iraqi border). Mari was once conquered by the kings of Akkad, but the kings of Ur preferred a peaceful relation. Shulgi thus married a princess of Mari. This gave them access to the important trade routes that crossed the kingdom. They appear to have had no desire or ability to establish contact with kingdoms further west.[125][126]

Administrative documents of the Ur III period refer to Martu, or Amorites, that is people speaking a Semitic language, coming from the 'West' (that's the meaning of their name), and often associated with a nomadic lifestyle and a tribal organization.[126][127] Amorite migrations from Syria and Upper Mesopotamia to Lower Mesopotamia had already started at the end of the Akkadian period, and continued after. For the Ur III period, there are mentions of approximately 600 Amorite individuals employed in the cities of Lower Mesopotamia, in approximately 900 documents, which is low compared to the documentation of the period. To some extent, they had blended into local society, some even bearing Akkadian and Sumerian names even though they were still defined as 'Amorites.' They were employed in various trades, with an apparent predilection for war. An elite guard seems to have been formed from Amorite elements. Some Amorites, such as Naplanum, a tribal leader and general, even held important positions in the Ur III Empire. Some of the Amorites who had migrated to Mesopotamia clearly remained on the margins of the Ur III Empire, probably remaining nomadic. These groups, particularly those called Tidnum, constituted a potential threat in the eyes of the Mesopotamians, which explains the negative stereotypes of the Amorites in Sumerian literature. The great walls erected by Shulgi and Shu-Sin seem to have been intended to stop or at least control their incursions. The Amorites are therefore in an ambivalent position, which is found in other periods of history, at once migrants, mercenaries, invaders, and nomads whose raids affected sedentary societies. The Amorites are often considered the true beneficiaries of the fall of the Ur Dynasty, since most of the kingdoms that dominated Mesopotamia in the following centuries were founded by Amorite leaders.[128][129][130][131]

The North and the Hurrians

Upper Mesopotamia was divided in several small kingdoms. The kingdom of Ur extended its influence along the Tigris and dominated for a time the city of Assur, and possibly Nineveh. They also had pacific and bellicose relations with the kingdom of Shimanun, located further north on the Upper Tigris. In the Khabur valley, the kingdoms of Urkesh (Tell Mozan) and Nagar (Tell Brak) remained autonomous.[132]

These kingdoms had a significant Hurrian component among their populations and were often ruled by dynasties of Hurrian origin. Contacts with these regions opened Lower Mesopotamia to Hurrian influences. The kings of Ur had subordinates with Hurrian names, some of whom became governors, and made offerings to Hurrian deities, such as the great goddess Shaushka of Nineveh.[133][134]

The Gulf and Indus Valley

International trade between Sumer and the Persian Gulf region was of great importance in the 3rd millennium BC. It provided Lower Mesopotamia with access to the countries of Dilmun (present-day Bahrain), Makkan (Oman), and Meluhha (probably the Indus Valley). The goods traded were raw materials such as copper from Oman, wood, ivory, and semiprecious stones. In the Ur III period, Guabba in the province of Girsu and Ur were the kingdom's main ports. A large fleet was controlled by the royal administration, and the vizier himself sometimes organized transactions, which testifies to the importance of this trade. However, it began to decline, while overland trade through Iran gained in importance.[127][135]

Trade with the Indus Valley, were the Harappan civilization flourished, is evidenced by several objects from this region found in Sumer and Susiana, such as seals and carnelian beads. This region was probably known as Meluhha in Sumerian texts. But the peak of this trade probably happened before the Ur III period, and it ended after 1900 BC when the Indus civilization collapsed.[136][137] The mention of a village named Meluhha in an Ur III tablet could be evidence that Harappan people settled in Lower Mesopotamia during the last centuries of the 3rd millennium BC.[138]

Remove ads

Culture and arts

Summarize

Perspective

Sumerian dominated the cultural sphere and was the language of legal, administrative, and economic documents, while signs of the spread of Akkadian could be seen elsewhere. New towns that arose in this period were virtually all given Akkadian names. Culture also thrived through many different types of art forms. Most of what remains has a political coloring, and these different art forms combined were intended to celebrate the power of the kings of Ur III, as P. Michalowski points out:[140] "the Ur III state utilized a complex, integrated programme of political messages aimed at the literate bureaucracy and the elites, exploiting different media, including public and private ceremony, monuments, inscriptions, year-names, and a whole range of poetic compositions designed for performance as well as for use in the schooling of future bureaucrats."

Religion

The official pantheon of the Ur dynasty was dominated by the god Enlil, king of the gods and god of kingship, worshipped in the holy city of Nippur. His spouse Ninlil was also an important divine figure. Her sanctuary at Tummal, near Nippur, was a major holy site in the kingdom, doted by the kings. An attempt to centralize the cults in the province of Nippur may have taken place at this time, in order to consolidate the cults of Enlil and Ninlil. The literary corpus also testifies to the primary role of Nippur in royal ideology. The cults of gods from foreign lands were also introduced into the main religious centers of Lower Mesopotamia, perhaps also as part of the concentration of cults in the capital cities.[141]

Chosen and enthroned by the gods, kings are invested with heavy religious duties. Ur III kings often sought the advice of the gods through omens before making important political or religious decisions.[142] They must organize the smooth running of their cult and thus follow the example of the pious king.[143] They constantly built and restored numerous temples and provided them with sumptuous offerings: divine furnishings such as thrones, or means of transport such as chariots or boats. These acts were deemed worthy of inclusion in their year names, alongside their military exploits. Monarchs also had ritual duties. They were assisted in this task by members of the royal family, including their wives and their sons and daughters who were enthroned as high priests or high priestesses of several important sanctuaries (Ur, Uruk, etc.). The provincial governors are responsible for the cult in their provinces, reproducing on their scale the role of the king.[144][145]

One of the peculiarities of the Ur period is the deification of kings, which took place from Shulgi (who follows the model of Naram-Sin of Akkad) and whose exact theological implications are debated. It resulted in the existence of a cult intended for the sovereigns during their lifetime, with the creation of cult statues of the deified kings, the accomplishment of sacrifices and festivals in their honor and the erection of several places of worship such as the temple of Shu-Sin excavated at Eshnunna.[146]

Shulgi's integration into the divine sphere is also reflected in his elevation to the status of husband of the goddess Inanna. The king is thus assimilated to her divine husband, the god Dumuzi. He also becomes the son-in-law of the god Nanna (Inanna's father), the brother-in-law of the god Utu (Inanna's brother), and the brother of the goddess Geshtinanna (Dumuzi's sister). The question of the existence of a "sacred marriage" (hierogamy) ritual symbolically representing the union of the king and the goddess is debated: some hymns evoke such a relationship, but no source documenting daily cult attests to the actual existence of such a rite.[147][148][149]

The cultic calendars of the various cities was punctuated by numerous festivals (ezen) dedicated to the main gods, which generally took place at regular intervals (every day, several times a month, or once a year).[150] The most important ones brought together the main officials of the kingdom as well as foreign emissaries,and generated substantial expenditure recorded by administrative texts. Some festivals followed the cycle of the seasons, or that of the stars, others had funerary symbolism or were linked to royalty or the families of provincial governors, etc. Among the most important are festivals linked to the lunar cycle which take place three times a month (eš3-eš3);[151] the festival of the celestial boat (ezem-ma2-an-na) dedicated to Inanna at Uruk;[152] various rituals of divine journeys such as the one which saw the statue of the goddess Ninlil travel on her sacred boat from Nippur to Tummal, commemorated by an hymn and a year-name of Shulgi;[153][62] the great festival of Inanna at Nippur which had takes place during the sixth month of the year,[154] etc.

- Inscription of Ur-Namma commemorating the restoration of the Eanna, the great temple of the goddess Inanna in Uruk. British Museum.

- Tablet from Puzrish-Dagan: account of expenditures, record of deliveries of animals for the festival of sowing seed (šu-numun a2-ki-ti). Reign of Amar-Sin), Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Detail of the reverse side of the Ur-Namma stele: two drummers with a big round drum, during festivities celebrating the building of a temple. Penn Museum.

Literature

During the Ur III period, royal inscriptions and texts relating to "belles-lettres" or rituals were almost exclusively written in Sumerian. This flourishing was greatly driven by the royal power, notably Shulgi, who sponsored the creation of a scholastic institution (the e2-dubba, often translated as "house of tablets") and thus the reform of the training of scribes.[155][80] This explains the strong political coloring of literary works, which are the product of "court literature," and are also sometimes labelled "propaganda."[156][157] However, the known versions of works datable to the time of the kings of Ur are essentially 18th-century BC copies, mostly from Nippur (a major cultural center and probably the place of origin of many of these literary pieces), written in schools by apprentice scribes. Changes could therefore have been made to these texts between these two periods.[158]

The royal ideology of Shulgi's reign is in many ways a continuation of that of the Akkadian period, in particular the reign of Naram-Sin (who also claimed to be a god), while seeking to distinguish itself from it in various ways. The Third Dynasty of Ur is a phase of return to properly Sumerian traditions, since official texts are written in this language (while it is spoken less and less in everyday life).[159] However, the notion of a Sumerian 'revival' or 'renaissance' to describe this period is misleading because archaeological evidence does not offer evidence of a previous period of decline.[160]

A major innovation of the Neo-Sumerian period (first seen in the literature of Gudea of Lagash, which possibly inspired that of Ur III kings[155]) is the celebration of the king's prominence was achieved during Shulgi's reign primarily through the writing of hymns that seem to have been written primarily to highlight his many qualities and thus consolidate royal ideology and legitimacy. These hymns are more generally part of a court literature that seems to have been composed during this period, as it serves the same ideological objectives. The schools established by Shulgi were explicitly aimed at training scribes capable of creating and copying these texts. The royal hymns are the most important: they highlight the king's remarkable qualities, his pious deeds and military exploits, as well as his physical vigor, intelligence and charisma. A group of love hymns with erotic overtones, notably dedicated to Shu-Sin and the divine couple Dumuzi-Inanna, is linked to the theme of sacred marriage.[161][59] These hymns are not just literature, since they were composed to be sung with musical accompaniment, notably during religious ceremonies (an hymn to Shulgi evokes their declamation in the temple of Enlil), which implies the presence of singers and court musicians, documented for the reigns of Shulgi's successors[162]

Epic literature flourished with the writing down of several stories once again linked to the royal dynasty, the myths relating to the exploits of three semi-legendary kings of Uruk: Enmerkar, Lugalbanda and Gilgamesh. The kings of Ur III, whose dynasty originated in Uruk, presented themselves as the relatives of these past heroes. Ur-Namma and Shulgi even called themselves "brothers" of Gilgamesh in certain inscriptions, since they claimed to be descendants of the latter's parents, including the goddess Ninsun[163][164][159]

Literature of a historiographical nature also has royalty as a major subject. An hymn probably commissioned by Shulgi or his mother, the Death of Ur-Namma, is a lament, mainly in the mouth of the goddess Inanna, about the death in battle of the king Ur-Namma, his funeral and descent to the Netherworld.[165][166] The earliest known copy of the Sumerian King List dates from the Ur III period. It offers a largely fictional reconstruction of past dynasties that ruled before losing it to another, from the legendary times when kingship was handed down from the heavens to the time of the king of Ur. It conveys an idea of an immemorial 'imperial' power unifying Mesopotamia through several legitimate dynasties, which is fictitious but serves the political discourse of the Ur III kings well.[167][168]

- Hymn to Ur-Namma. Louvre Museum.

- Hymn to Shulgi, described as the "ideal king." Nippur, Penn Museum.

Architecture

The kings of Ur were very active builders. The majority of their official inscriptions (as well as some year names) commemorate the constructions and restorations they sponsored. Administrative tablets also document public constructions.[169]

The kings of Ur are best known for the work they carried out in the great Sumerian religious complexes: Ur, Eridu, Uruk and Nippur. The center of Ur is the best known: the sanctuary of the god Nanna was organized around two large courtyards, the largest, built on a terrace including shrines and the ziggurat (e2-temen-ni-gur, "House whose foundation is clad in terror"). To the south were other major buildings: the Giparu, divided between the part serving as the residence of the high priestess of Nanna and the temple of the goddess Ningal, the Ganunmah which probably served as a treasury and store house, while the Ehursag was a royal palace. Further south still stood a religious building with underground vaulted tombs, often identified as the mausoleum of Shulgi and Amar-Sin.[170]

These religious complexes also featured imposing stepped temples, the ziggurats, which are generally considered innovations of this period, although they are a continuation of earlier temples built on terraces during the Uruk and Early Dynasty periods. In the Ur III period, these buildings are rather known by the Sumerian term gi-gu3-na, and the kings of Ur may have planned to build one in each of their provincial capitals (erosion of the sites has led to the disappearance of an unknown number of them).[171] These were vast buildings with a rectangular base (c. 60 × 45 meters at Ur), composed of at least two superimposed terraces, surmounted by a high temple. Their religious function remains controversial, but their monumental aspect is evident. They constitute the best architectural illustration of the capacity of the kingdom of Ur to mobilize significant resources and to plan large-scale works thanks to its administrative apparatus. To build them, the master builders took up and perfected the architectural techniques they had inherited from their predecessors: development of standardized bricks, ingenious architecture alternating bricks laid on edge and bricks laid flat, mass of raw bricks covered with a coating of more solid baked bricks, chaining of reeds and anchoring with braided reed ropes.[172][173]

Visual Arts

Art from the Ur III period come in several forms of sculptures. Most of what is known is a celebration of the royal figure, reflecting the same ideology as the court literature of this period.[174]

Monumental reliefs are particularly well represented by the stele of Ur-Namma, carved from limestone and measuring over 3 meters high (10 ft.), which is preserved in fragmentary form. It consists of several registers commemorating the king's construction activities for the gods of Ur, Nanna and Ningal, as well as the festivities celebrating the construction, with offerings and musicians, in a narrative style reminiscent of the hymns of that period. One register shows Ur-Namma pouring libations in front of the enthroned gods, Nanna holding the rod and the ring that symbolize royalty.[175]

Texts tell us that royal statues were produced during this period, particularly for the cult of deified kings. But almost none of these works of art have survived. Fragmentary sculptures of Shulgi and heads that were originally part of statues bear witness to this art form. Their style is similar to that of the statues from the reign of Gudea of Lagash (a contemporary of Ur-Namma). Small sculptures of animals and supernatural creatures were used as votive offerings, and also as weights.[176]

Another form of sculpture was not intended for display: foundation figures. They were buried beneath a temple built or restored by a king, along with an inscription commemorating this pious act. During the earlier periods, they usually took the form of clay or copper pegs, sometimes surmonted by a carved god, but most foundation figures from this period, made in copper alloy, depict the king. He holds a basket above his head, containing bricks and mortar, symbolizing his role as king-builder.[177]

The iconography of cylinder-seals was less varied during the Ur III period than it had been during the Akkadian period, since mythological and narrative scenes were set apart. The most typical composition in Ur III glyptic art is the presentation scene, showing the owner of the seal being presented by a protective goddess before a king seated on a throne. Sometimes the king is depicted as a god; in some cases, a god replaces the king.[178] A short inscription often identifies the owner of the king, an official, and the king he serves, praying for the latter's health. These seals thus seem to be linked to the existence of a high class of high officials of the state close to the sovereign and to the affirmation of the sacred aspect of the latter's function.[179][180]

- Fragment of the Stele of Ur-Namma: the god Nanna on his throne, holding the ring and the rod. Penn Museum.

- Foundation figurine of Ur-Nammu, commemorating the restoration of Enlil's temple in Nippur. National Museum of Iraq.

- Cylinder seal showing a worshipper led by a protective goddess in front of a King seated on a throne (Ur-Namma?). British Museum.

Remove ads

Aftermath and legacy

Summarize

Perspective

The fall of Ur had a significant resonance in Mesopotamia, as that of Akkad had before it. This event was probably already considered a major turning point in the history of Mesopotamia in ancient times. A new era began, the Old Babylonian period (c. 2000–1600 BC). The dynasties that succeeded Ur, before those founded at Isin and Larsa (Isin-Larsa period), claimed its heritage: their titles took up those of the kings of Ur, they continued for a time to be deified and to patronize an art and literature in continuity with those of the Neo-Sumerian period. Under the kings of Isin, texts of "lamentation" were written, commemorating in dramatic poetic language the fall of the kingdom of Ur and its great cities (Ur, Uruk, Nippur, and Eridu). They actually aimed to justify the fall of Ur and to legitimize the rule of the new masters of southern Mesopotamia by presenting them as divine decisions. This vision of a legitimate succession is also manifested by the fact that they added their names to the Sumerian King List after those of the kings of Ur. The hymns and stories relating to the kings of Ur III, notably Ur-Namma and Shulgi, were still copied and perpetuated the memory of their brilliant reigns, as were the apocryphal letters of the kings of Ur, notably those referring to its fall, which were copied in schools.[182][183] Nonetheless the Ur III dynasty did not equal the prestige of the kings of Akkad in Mesopotamian historical tradition. It may be explained by the fact that the kings of Ur did not make military conquest as impressive as those of their predecessors.[184]

Remove ads

See also

References

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads