Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

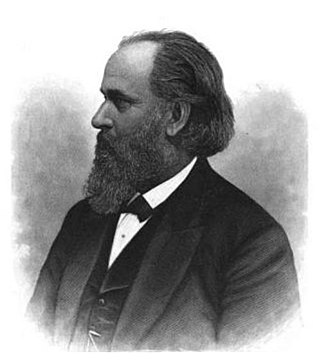

Adolph Strauch

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Adolph Strauch (August 30, 1822 – April 25, 1883) was a Prussian American landscape architect who conceived the "landscape lawn" design. He applied his thinking to the layout of Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati, Ohio, which won him international acclaim. Strauch also advised and helped design several other parks and cemeteries, and laid out Eden Park, Burnet Woods, and Lincoln Park in Cincinnati.

Remove ads

Biography

Summarize

Perspective

Strauch was born August 30, 1822, in the town of Eckersdorf in Lower Silesia, which was then part of the Kingdom of Prussia.[1] His father managed Schloss Eckersdorf, the estate of Count Anthony Alexander von Magnis, and Strauch grew up on the estate.[2] Adolph attended the local high school, where he studied botany.[2]

In 1838, Count Magnis obtained an apprenticeship for the young Strauch at the Imperial Gardens at Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna, Austria.[2][a] He studied landscaping and gardening under Prince Herman von Pückler-Muskau,[2] The prince was highly regarded for his work on Muskau Park, the family estate in Upper Lusatia, and had published a well-regarded book on landscaping, Hints on Landscape Gardening.[4]

Schönbrunn Palace had formal, geometric gardens rivaling the gardens of Versailles.[4] Pückler-Muskau, however, was much more interested in the Picturesque landscape theories of Sir Humphry Repton and John Nash.[4] Strauch apprenticed under the prince for six years.[2]

At the prince's urging,[4] Strauch left Vienna in January 1845 and traveled through Germany, The Netherlands, and Belgium, studying the landscaping of estates and gardens.[1] He carried letters of reference from the prince, which gave allowed him to not only study landscape design but the gardening operations of these establishments.[4] He spent longer periods at large estates in Berlin, Hamburg, The Hague, and Amsterdam.[1] At the beginning of 1846, Strauch spent three months working for Belgian horticulturist Louis van Houtte at his vast nursery near Ghent.[1][4]

Leaving Ghent, Strauch moved to Paris, France. He worked as a gardener there, and studied the great gardens of the city and surrounding area.[1] Several times he visited Père Lachaise Cemetery, which at that time was one of the very few garden cemeteries in Europe.[4][b]

The French Revolution of 1848 broke out in February of that year, and soon much of Europe was engulfed in the Revolutions of 1848. A supporter of German unification and democracy,[5] it was unsafe for Strauch to return to Germany, so he relocated to London, England,[1] where he began working for the Royal Botanic Society at Regent's Park.[6]

When the Great Exhibition opened in Hyde Park on May 1, 1851, Strauch — who could speak German, English, French, Polish, and Czech[6] — found work there as a guide for distinguished visitors.[1] When wealthy Cincinnati dry goods merchant Robert Bonner Bowler visited the Great Exhibition, he had trouble gaining entry. Strauch spotted him and helped him win admittance.[1] Grateful for Strauch's help and impressed with how polite he was, Bowler invited him to visit Cincinnati should he ever find himself in the United States.[7]

Remove ads

American sojourn

Summarize

Perspective

There was extensive press coverage of Texas and the American Southwest at the time in British newspapers, and many people were enthralled by what was described as a near-paradise.[5] The Great Exhibition closed on October 15, 1851, and Strauch did not want to return to Regent's Park. Anatoly Demidov, Prince of San Donato, had asked Strauch to take charge of the grounds at Villa San Donato in Florence, Italy. Strauch turned him down.[7]

Strauch sailed to the United States, arriving in Galveston, Texas, on November 5, 1851.[7] He intended to earn his way across America by writing newspaper articles for publication in Britain and Germany.[5] Strauch was disappointed to find the Texas shore to be mostly marshes, and he disliked the hot, humid inland climate.[7] Strauch decided to make the trek west to San Antonio. He intended to proceed northwest into the New Mexico Territory, but discovered that the Comanche in the area were extremely unfriendly to visitors and that he would need an armed force to accompany him.[5]

After spending the winter among German expatriates in San Antonio and nearby towns, Strauch decided to return to Britain.[5] In the late spring of 1852,[8] however, he learned that a member of the wealthy Cushing family of Boston, Massachusetts, was looking for a new head landscape gardener. The position appealed to him, as Boston's parks and gardens were much talked about in horticultural circles.[7]

Intending to see more of the United States, Strauch took a steamer from New Orleans, Louisiana, up the Mississippi River to Cincinnati. He intended to catch a train at Cincinnati that would take him through Ohio and along the St. Lawrence River to Niagara Falls and then east to Boston. His steamer was slow to arrive in Cincinnati, however, and he missed his train.[7]

Stuck in Cincinnati overnight, Strauch decided to seek out Robert Bowler.[7] Strauch discovered that Cincinnati had a flourishing horticultural community: It was home to important journal The Western Horticultural Review, the Ernst family owned the immense Spring Garden nursery, and Bowler turned out to be strongly interested in promoting landscape gardening and horticulture.[6] The city also had a well-established German-American community.[8]

Remove ads

Early career

Bowler asked Strauch to become head gardener at his Mount Storm estate. Strauch agreed, and stayed for the next two years.[7] Having read and been deeply impressed by the first three volumes of Alexander von Humboldt's Cosmos: A Sketch of a Physical Description of the Universe,[1][c] The estate's landscaping design and plantings were incomplete,[2] and Strauch began to implement his ideas for a "lawn landscape system" at Mount Storm.[7][9] He already had well-defined ideas for what landscape design should encompass: Space unified by panoramas and vistas; no enclosures, hedges, or fences; small lakes; well-placed statuary framed by suitable trees; lawns and flowers; and tasteful service buildings.[8]

His work for Bowler earned him much local notice, and he was also hired to landscape Henry Probasco's Oakwood, George K. Schoenberger's Scarlet Oaks, William Neff's The Windings, the Robert Buchanan House, and the William Resor House.[10] All these designs were in the English landscape garden tradition.[2]

After leaving Mount Storm, Strauch toured the U.S. and Canada, observing the landscape and native plants.[7]

Spring Grove

Summarize

Perspective

After his return to Cincinnati, Strauch was hired by the trustees of Spring Grove Cemetery on October 8, 1854, to be their head gardener.[11]

The state of Spring Grove in 1854

Organized in February 1845,[12] Spring Grove Cemetery lay in a valley surrounded by hills. Within the valley were several areas of taller, flat terrain; a number of ravines and swales; and wetlands.[13] At the time of Strauch's hire, the cemetery had 206 acres (83 ha),[14][d] of which 56.84 acres (23.00 ha) were surveyed and laid out.[17]

The organizers of Spring Grove traveled to see the famed cemeteries of the East Coast: Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York City, New York; Laurel Hill Cemetery near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; and Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. They hired John Notman, the designer of Laurel Hill, to develop Spring Grove's first master plan.[18] Notman's proposed geometric design was impractical for the highly varied geography and lacked the naturalism which had so impressed them at Mount Auburn.[13]

Declining to implement Notman's design,[18] the cemetery trustees hired local architect and landscape designer Howard Daniels. He was toured the rural cemeteries of the east, and returned to Cincinnati to design a burial ground in the Picturesque style. With the assistance of local surveyor and civil engineer Thomas Earnshaw, Daniels put roads in low-lying areas and reserved higher ground for burials.[13] Daniels believed every lot should face a road or footpath, and laid out a labyrinth of 6-to-10-foot (1.8 to 3.0 m) wide footpaths between roads.[19] Grading of land was not done until a lot was sold.[20] Daniels lacked the funds[13] to reclaim the 5 acres (2.0 ha) of swamp at the front of the cemetery along Hamilton Road,[19] so the trustees leased this land to farmers for use as pasture.[13]

Daniels served two years at Spring Grove,[21] implementing his plan with the help of his assistant, Dennis Delaney.[22] By 1847, 23 acres (9.3 ha) had been surveyed and laid out.[23] Delaney was appointed the new superintendent. Cemetery improvements were planned and made by Delaney in cooperation with a committee appointed by the board of trustees which included director Robert Buchanan and Thomas Earnshaw.[18] Earnshaw died in August 1850.[24] Delaney served as superintendent until fall 1856[25] or 1857.[26] Until the employment of Strauch, landscaping decisions during Delaney's superintendency were made monthly by a committee of cemetery leaders.[22]

Until lot sales brought in cash, the trustees lacked the money to landscape Spring Grove, so they encouraged lot owners to improve lots on their own. Lot owners soon planted an enormous variety of decorative grasses, vines, shrubs, flowers, and weeping trees. Fearing trespassers would harm these plantings, they erected enclosures around their lots. Soon, 75 percent of all lots at Spring Grove were surrounded by hedges or cast iron, wrought iron, or post-and-chain fences. Enclosures were only supposed to be 2 feet 8 inches (0.81 m) high, but enforcement was lax and most were much higher.[13] Some lots were so full of burials that a dozen headstones crowded onto them.[20]

A portion of the cemetery was cut off when the Cincinnati, Hamilton and Dayton Railway was built. The railway was chartered by the state of Ohio in March 1846.[27] The state granted the railroad the right to appropriate land, at a fair market price, for its route.[28] By October 1849, the railroad had determine that its line should cross Spring Grove Cemetery.[29] Cemetery trustees sued to block the railroad, but their request was denied by a court on December 28, 1849.[30][e] To protect lot holders and visitors from rail cars crossing the cemetery grounds, Spring Grove Cemetery, at its own expense, built a viaduct which elevated trains over its land. The cost was $9,000 (equivalent to $263,000 in 2024).[33] The first trains ran on September 18, 1851.[34] The viaduct cut off 13 acres (5.3 ha), which were used only by workmen.[35]

Strauch's "lawn landscape" theory

Strauch's vision for any cemetery, estate, or park was for a unified landscape.[36] Strauch was not only deeply influenced by Humphry Repton's theories of English landscaping and Pückler-Muskau's emphasis on maintaining the appearance of nature without human interference,[36] but by the European interpretation of traditional Chinese park design. Strauch believed in landscaping that did more than merely imitate nature; the landscape designer should embellish nature with art.[37] Visual unity was all-important, especially when complex elements were present. Enhancing nature meant creating dramatic visuals, and the massing of elements was key to this.[36]

To ensure visual unity, Strauch banned the use of fences and hedges around plots,[38][36][f] and forbade the use of private plantings, no matter how large or small, on plots.[36] All grading of a section was done prior to sale of lots, to ensure visual connectivity and an appropriate transition to the next landform or feature.[20] The overall planting scheme of the section was also pre-determined by the cemetery landscape gardener.[36] Groupings of trees were juxtaposed against well-mowed meadows,[g] creating areas of light and dark[39] which created dramatic visuals for the visitor.[36]

Trees, shrubs, and flowers at Spring Grove were selected on aesthetic grounds and for their symbolism, but in all cases practical considerations like the nature and wetness of the soil, availability of light for light-sensitive plants, and adaptability to the southern Ohio climate could overrule these choices.[20] In all cases, vegetation was to be luxuriant and planted in deep banks (not in single rows or in isolation).[36] Strauch favored evergreens for their darker colors, against which more brilliant plants would stand out. He often used trees with brilliant autumn colors like scarlet maple, scarlet oak, sour gum, sugar maple, and tulip tree to alleviate the gloominess of evergreens.[39][h]

In accordance with Pückler-Muskau's views, Strauch required that roads wind about, suddenly revealing spectacular vistas.[40] Dead-end and perimeter roads were banned.[40] Roads had to interconnect so that visitors could vary their route and experiences at the cemetery. When roads had to run parallel to one another, they were to be separated by a landform such as a hill or valley.[40] The corners of road junctions were reserved for plantings, and not to be sold as burial plots.[20] These corners were to contain plants with various colors, to provide a gentle transition from brightness to shade.[39] Roadways were, at all times, to be kept in excellent shape.[36]

Strauch approved of footpaths as a means of connecting roads and providing access to the interior of sections.[40] The same planting rules and requirement for visual drama governed footpaths as well as roads.[36] Spring Grove cemetery had created numerous graveled footpaths, but these quickly became weedy and difficult to maintain. Strauch agreed that graveled footpaths should be removed in favor of graded, hard-packed earth or clearly delineated close-clipped grass.[20]

Like Pückler-Muskau, Strauch favored the use of ponds and small lakes to create thrilling visuals. These were to be highly irregular in shape, with small islands and deep bays to fool the eye into believing they were much larger than they seemed. The man-made nature of the shores were concealed by thickets of shrubs or dense copses of trees. To create dramatic entry points for visitors, and to allow light to hit the water, only occasionally would there be a break in the plantings or a broad, grassy bank.[40]

Under Strauch, the cemetery's landscape gardener had complete control over the monuments and plantings in private lots. He strongly discouraged the use of headstones, and barred them in plots capable of holding a large number of burials.[38] (Too many headstones in a plot made it look like a commercial stone-seller's display yard, he said.)[41] If headstones were used, he limited them to 2 feet (0.61 m) in height,[36] and barred wooden markers because they deteriorated so quickly.[20] Mausoleums and vaults were prohibited.[42][i]

During Strauch's time administering Spring Grove, the first large above-ground monuments appeared.[43] He permitted only a single large memorial per lot, whether single-burial or family plot.[36] This large memorial had to be placed in the center of the lot, and all such objects had to be beautiful, of excellent craftsmanship, and high-quality materials, and all large memorials had to be approved by the cemetery's board of trustees.[20] These large monuments were framed or backgrounded by trees and shrubs, and no other large plantings were permitted on the lot.[20] These "framing" plantings were to be evergreens, and monuments could only be white, gray, or rose so that they would stand out against the evergreens.[39]

Maintenance and other buildings at the cemetery were massed, and architect-designed to connect visually to their setting as well as ensure their beauty.[36]

Strauch also peppered Spring Grove with outdoor statuary. These were not intended as monuments or memorials, but simply because they added beauty to the cemetery.[44]

Implementing change

Strauch insisted on strict adherence to his rules.[36] He encountered stiff resistance from some cemetery trustees, who felt rigid rules for headstones, memorials, and plantings would reduce plot sales to nothing.[7][36] These board members tried to have him fired, but were unsuccessful.[7]

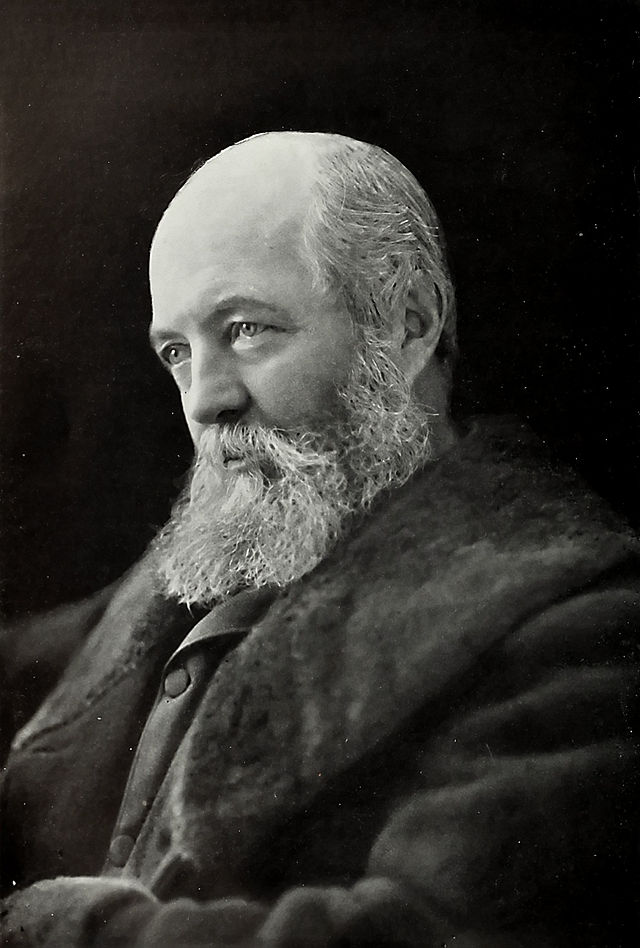

— Frederick Law Olmsted, 1875[45]

To implement his plan, Strauch removed nearly all existing footpaths[19] and cut in half[46] the cemetery's 12 miles (19 km) of roads.[35] He remodeled sections that had been planted by his predecessors, and even replanted and reorganized private lots when their owners requested it.[36]

Henry Earnshaw, son of Thomas Earnshaw, was appointed Spring Grove's superintendent after Delaney's departure.[25][47] Earnshaw had served as civil engineer and surveyor of Spring Grove under Delaney, and had carried out Strauch's landscaping plans.[48] The board wished to save money[47] and combine the office of superintendent with that of head gardener. Earnshaw did not wish to resign, however, and the board struggled for some time to convince him.[48] Strauch was finally given the job of superintendent in 1859,[49] and gained control over all grading, planting, pruning, road-building, and lots maintenance.[20]

Strauch began working on the swampy area of the cemetery in 1851. He planned to excavate part of the land to create a 6-acre (2.4 ha) lake into which various springs would drain. At the center of lake was a small waterfall.[35] Actual construction did not begin until 1857,[50] at which time Strauch also planted the acreage cut off by the railroad viaduct with trees.[51] By 1869, he had replaced the entire swampy area with seven ornamental lakes and ponds.[19] He installed fountains in several of these bodies of water in 1876 to improve water circulation and reduce algae growth.[19]

Strauch also diversified the number of species of trees at Spring Grove. In 1857, there were 200 species of trees and shrubs on the property. By 1865, he had planted another 200 varieties. That year alone, he imported 400 American holly trees from Kentucky.[19] Five years later, he imported a large number of shrubs, trees, and vines from England.[52] He added several dozen Southern magnolias in 1876, which had been grown in Memphis, Tennessee.[53] Strauch imported evergreens from the Caucasus, Himalayas, and Rocky Mountains. Some of the more notable trees he added were Canadian poplar, Chinese tree of heaven, Corsican pine, European alder, French tamarisk, Norway spruce, Persian lilac, and Scotch pine.[52]

Strauch also sought out beautiful birds and waterfowl for Spring Grove.[45] These had the added advantage of keeping the lakes free of much unwanted plant life, and kept the lakes from becoming stagnant.[54]

He continued to expand his understanding of landscape gardening, too, and in 1863 toured Europe to study agricultural grounds, cemeteries, public parks, royal parks, and zoological gardens.[45]

By the 1860s, Strauch's work at Spring Grove was already highly acclaimed.[37] Strauch had a world-wide reputation as a landscaper, and Spring Grove was admired throughout the United States as a model cemetery.[7] French landscape architect Édouard André highly praised Strauch's work.[55] Frederick Law Olmsted, the father of American landscape architecture,[56] said Strauch's Spring Grove was the best landscaped site in America.[57][j] Olmsted said that when he needed inspiration, he visited Spring Grove.[58] Famed early 20th century landscape gardener Ossian Cole Simonds, who worked with Strauch at Graceland Cemetery, called Spring Grove "the most beautiful cemetery in the world".[58]

With Spring Grove Cemetery, Strauch is widely acknowledged as the creator of the "lawn plan",[57] "lawn system",[45] or "landscape lawn plan" of landscape design.[2] The "lawn plan" was revolutionary, landscape architecture historian Noël Dorsey Vernon says. Cemeteries which used the concept had few monuments and sculptures, and these were almost always framed by trees.[10]

Remove ads

Other work

Summarize

Perspective

Strauch's success at Spring Grove led other cemeteries and parks to request his advice and assistance.[37] Identifying all the projects he worked on is difficult, because Strauch refused to accept payment for these services. For him, educating others about good landscape design was all the payment he wanted.[59]

Among the projects Strauch is known to have worked on:

- Advised on the design of Mt. Olivet Cemetery in Memphis, Tennessee in 1860[60]

- The formation of Oak Woods Cemetery near Chicago, Illinois, in 1864[61][62][63]

- The grounds of Amherst College in Amherst, Massachusetts, in 1865[45]

- Forest Lawn Cemetery in Buffalo, New York, in 1866[45]

- With architect Gordon W. Lloyd, the ground and planting plans, and location of structures, at Woodmere Cemetery in Detroit, Michigan, in 1867[59]

He is known to have been consulted by Graceland Cemetery in Chicago,[62][57] West Laurel Hill Cemetery near Philadelphia,[62] and Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis, Indiana,[45] in the 1860s, and advised on Saint Mary Cemetery in St. Bernard, Ohio, in the 1870s.[62][61] Laurel Hill Cemetery[61] and Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York,[62] are known to have utilized his ideas during their redevelopment in the 1870s.

Strauch is also known to have provided advice or designs for cemeteries or parks in Buffalo, Chicago, Cleveland, Hartford, Nashville,[7][64][58][62] and Toledo.[58]

Strauch also designed portions of the Cincinnati park system,[58] and provided early designs for the city's Eden Park.[59][62] He also designed Burnet Woods, Lincoln Park, and the original grounds of the Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden.[65]

Remove ads

Impact

Adolph Strauch was very highly respected by his contemporaries.[62] He is, however, little known today. Several reasons were suggested by landscape design historian Noël Dorsey Vernon: He worked primarily in the Midwestern United States at a time when only those who worked for large firms on the East Coast gained any prominence. He wrote little in English, and his writings in German were not translated.[61][k]

Remove ads

Personal life

Strauch became a naturalized American citizen on November 2, 1876.[66]

He married Mary Chapman[8] in 1872.[65] The couple had four children: Adolph, Otto, Louise, and Mary.[65]

Adolph Strauch suffered a stroke on April 12, 1883.[67] The effects gradually spread from his legs upward, leaving all but his head paralyzed. He died at home on April 25, 1883.[65] He was buried on Strauch Island at Spring Grove Cemetery.[68][69] He had designed the site for himself.[65]

Remove ads

Notes

- Volume four did not see publication until 1858, and volume five until 1862.

- The railroad told the cemetery it would pay for the land later. The cemetery sued. The Ohio District Commercial Court ruled in favor of the railroad,[31] but the decision was reversed in favor of the cemetery by the Supreme Court of Ohio.[28][32]

Remove ads

References

Bibliography

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads