Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

And yet it moves

Phrase attributed to Galileo Galilei on being forced to recant his scientific view From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

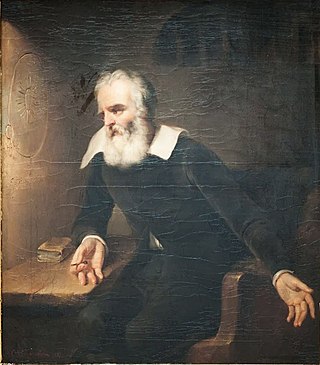

E pur si muove or Eppur si muove [epˈpur si ˈmwɔːve] ('And yet it moves' or 'Although it does move') is an Italian phrase commonly attributed to the Italian physicist and astronomer Galileo Galilei (1564–1642). The Catholic Church persecuted Galileo for promoting the Copernican model of the Solar System in which the Earth moves around the Sun, which contradicted Catholic orthodoxy that that the Earth remained fixed in the center of the universe.

According to popular legend, Galileo muttered this in 1633 after the Roman Inquisition forced him to recant his claims, though this is likely apocryphal.

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

According to Stephen Hawking, some historians believe this episode might have happened upon Galileo's transfer from house arrest under the watch of Archbishop Ascanio Piccolomini to "another home, in the hills above Florence".[1] This other home was also his own, the Villa Il Gioiello, in Arcetri.[2]

The earliest biography of Galileo, written by his disciple Vincenzo Viviani in 1655–1656, does not mention this phrase, and records of his trial do not cite it. Some authors say it would have been imprudent for Galileo to have said such a thing before the Inquisition.[3][4][5]

The event was first reported in English print in 1757 by Giuseppe Baretti in his book The Italian Library:[6]: 357

The moment he was set at liberty, he looked up to the sky and down to the ground, and, stamping with his foot, in a contemplative mood, said, Eppur si muove, that is, still it moves, meaning the Earth.[7]: 52

The book became widely published in Querelles Littéraires in 1761.[8]

In 1911, the words E pur si muove were found on a painting which had just been acquired by an art collector, Jules van Belle, of Roeselare, Belgium.[9] This painting is dated 1643 or 1645 (the last digit is partially obscured), within a year or two of Galileo's death. The signature is unclear but van Belle attributed it to the seventeenth century Spanish painter Bartolomé Esteban Murillo. The painting would seem to show that some variant of the Eppur si muove anecdote was in circulation immediately after his death, when many who had known him were still alive to attest to it, and that it had been circulating for over a century before it was published.[6] However, this painting, whose whereabouts is currently unknown, was discovered to be nearly identical to one painted in 1837 by Eugene van Maldeghem, and, basing their opinions on the style, many art experts doubt that the van Belle painting was painted by Murillo, or even that it was painted before the nineteenth century.[10]

United States Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia gave an "E pur si muove" award to district court judges whose opinions were overturned by appellate courts but later vindicated by the Supreme Court.[11]

Remove ads

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads