Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

China–United Kingdom relations

Bilateral relations From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Chinese–United Kingdom relations (simplified Chinese: 中英关系; traditional Chinese: 中英關係; pinyin: Zhōng-Yīng guānxì), more commonly known as British–Chinese relations, Anglo-Chinese relations and Sino-British relations, are the interstate relations between China (with its various governments through history) and the United Kingdom. The People's Republic of China and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland established diplomatic relations on 17 June 1954.[1]

In the 19th century, the British Empire established several colonies in China, most prominently Hong Kong, which it gained after defeating the Qing dynasty in the First Opium War. Relations between the two nations have gone through ups and downs over the course of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. The UK and China were on opposing sides during the Cold War, and relations were strained over the issue of Hong Kong.[2][3] In 1984, both sides signed the Sino-British Joint Declaration, which eventually led to the handover of Hong Kong to China in 1997.

Following the conclusion of the Cold War and the handover of Hong Kong, a period known as the "Golden Era" of Sino-British relations began with multiple high-level state visits and bilateral trade and military agreements.[4][5] This roughly 20-year period came to an abrupt end during the 2019–2020 Hong Kong protests and the imposition of the 2020 Hong Kong national security law, which was viewed in the UK as a serious breach of the Sino-British Joint Declaration.[6][7] In the years following relations have deteriorated significantly over various issues including Chinese company Huawei's involvement in UK's 5G network development, espionage, and human rights abuses in Xinjiang.[8][9] However, despite this, China is the UK's fifth-largest trading partner as of 2025.[10]

Remove ads

Chronology

Summarize

Perspective

England and the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644)

In the 1620s, English ships began arriving at Macau, a port city leased by China to Portugal. During this period, an English merchant vessel named The Unicorn sank near Macau. The Portuguese salvaged several cannons, specifically sakers, from the wreck and sold them to the Chinese around 1620. These cannons were then replicated by the Chinese as the Hongyipao, marking an early instance of military technology exchange.

On 27 June 1637, a fleet of four heavily armed English ships commanded by Captain John Weddell reached Macau in an effort to establish trade relations with China. This venture was not sanctioned by the East India Company but was instead organized by a private consortium led by Sir William Courten, with King Charles I personally investing £10,000. The Portuguese authorities in Macau, bound by their agreements with the Ming court, opposed the English expedition. This opposition, coupled with the English presence, quickly provoked the Ming authorities.

Later that summer, the English force captured one of the Bogue forts at the mouth of the Pearl River and engaged in several weeks of intermittent skirmishes and smuggling operations. The situation deteriorated further, leading the English to rely on Portuguese mediation for the release of three hostages. Eventually, the expedition withdrew from the Pearl River on 27 December 1637. The fate of the fleet afterward remained uncertain.[11][12][13]

Great Britain and the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911)

The relationship between Great Britain and the Qing Dynasty evolved over several centuries, shaped by diplomacy, trade, military conflict, and the broader dynamics of empire.

Early contact included the 1685 visit of Michael Shen Fu-Tsung, a Chinese Jesuit, to Britain, where he met King James II.[14] Trade officially began in 1699 when the East India Company was permitted to conduct business in Guangzhou (Canton), marking the start of sustained commercial relations.[15]

In 1784, the Lady Hughes Affair, where a British gunner's salute led to unintended deaths, heightened tensions. This foreshadowed the cultural and legal misunderstandings that would plague future interactions. High-level diplomatic efforts followed, such as the Macartney Embassy of 1793 and the Amherst Embassy of 1816, both of which failed to establish equal diplomatic footing with the Qing court.

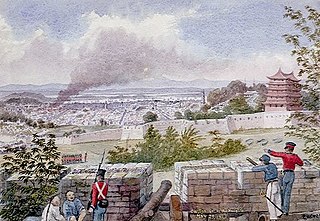

By the 1820s and 1830s, British merchants had turned Lintin Island into a hub for the opium trade.[16][17] This illicit commerce contributed directly to the First Opium War (1839–42). Prior to the war, the East India Company's monopoly on Chinese trade was abolished (1833–35), prompting efforts by successive British governments to maintain peace. However, figures like Lord Napier took a more provocative stance, pushing for deeper market access, despite the Foreign Office under Lord Palmerston favoring a less confrontational approach [18]

The war culminated in a decisive British victory. British motivations were framed by Palmerston's biographer as a confrontation between a dynamic, modern trading nation and a stagnant autocracy.[19] However, critics such as the Chartists and young William Ewart Gladstone condemned the war as morally reprehensible, pointing to the devastation caused by opium addiction.[20][21][22]

A temporary peace was brokered with the Convention of Chuenpi in 1841, though it was never ratified. The conflict formally ended with the Treaty of Nanking in 1842, which ceded Hong Kong Island to Britain and opened five treaty ports to international trade.[23] The Treaty of the Bogue followed in 1843, granting Britain most-favoured-nation status and legal extraterritoriality.

Throughout the mid-19th century, British influence in China expanded. From 1845 to 1863, the British Concession in Shanghai was established, later becoming part of the Shanghai International Settlement. The Second Opium War (1856–60) further entrenched British power. Following military successes, including the sack of the Old Summer Palace in 1860, the Convention of Peking granted Britain control of the Kowloon Peninsula and led to the establishment of a British legation in Beijing by 1861.

British consulates soon appeared across Chinese territory, including in Wuhan, Kaohsiung, Taipei, Shanghai, and Xiamen. Meanwhile, domestic unrest occasionally erupted, such as the 1868 Yangzhou riot targeting Christian missionaries. Despite such challenges, skilled diplomats like Li Hongzhang (1823–1901) continued efforts to mediate Qing engagement with Western powers.

Technological integration followed. From 1870 to 1900, Britain developed and operated a telegraph network linking London to key Chinese ports.[24] Diplomatic ties were formalized further when China opened a legation in London in 1877, headed by Guo Songtao. Britain also advised on the Ili Crisis (1877–81), reflecting its growing influence in Qing foreign affairs.

The late 19th century saw geopolitical adjustments. After Britain's annexation of Burma in 1886, the Burma Convention acknowledged British occupation while maintaining China's symbolic suzerainty through continued tribute payments.[25][26] Conflict between Britain and Tibetan forces in Sikkim led to the Treaty of Calcutta (1890), by which China recognized British control over northern Sikkim. A further agreement in 1890 fixed the border between Sikkim and Tibet.[27]

Britain's global influence was also felt in individual incidents, such as the 1896 detention of revolutionary Sun Yat-sen in the Chinese Legation in London. British public pressure led to his release, illustrating the political significance of diaspora activism.

The 1898 Convention for the Extension of Hong Kong leased the New Territories to Britain for 99 years, and that same year, Britain secured a lease on Weihai Harbour in Shandong. An odd footnote occurred in December 1898, when the arrival of four young English women in Shanghai sparked public commentary and minor diplomatic tensions.[28][29][30][31]

The turn of the century brought renewed conflict during the Boxer Rebellion (1900–1901), a violent anti-foreigner uprising suppressed by an allied force led by Britain and Japan. The resulting Boxer Protocol imposed heavy penalties on the Qing regime. Britain continued to assert influence over Tibetan affairs, most notably through the 1906 Anglo-Chinese Treaty on Tibet, which Britain interpreted as limiting China to nominal suzerainty.

By 1909, British consulates in Taiwan were closed following Japan's assertion of sovereignty, marking a shift in East Asian power dynamics. This period closed with Britain entrenched as a dominant force in China's foreign relations, trade, and territorial concessions.

Britain and the Republic of China (1912–1950)

Between 1912 and 1950, relations between Britain and the Republic of China (ROC) evolved significantly, marked by shifting alliances, conflict, diplomacy, and eventual disengagement.

Although Sun Yat-sen, who later became the founding father of the Republic of China, was rescued by British diplomats from Qing agents in 1896, early British involvement with Chinese political affairs was often shaped by colonial interests and imperial competition.

During World War I, in 1916, Britain recruited tens of thousands of Chinese labourers into the Chinese Labour Corps to support the war effort on the Western Front. On 14 August 1917, China officially joined the Allies, aligning itself with Britain in opposition to the Central Powers.

However, tensions emerged after the war. On 4 May 1919, the May Fourth Movement erupted in response to the Chinese government's failure to secure benefits from the postwar settlement. Britain had supported its treaty ally Japan over the contentious Shandong Problem, contributing to a broader Chinese disillusionment with Western democracies and a turn toward the Soviet Union for ideological and political inspiration.

At the Washington Naval Conference (November 1921–February 1922), Britain joined other powers in signing the Nine-Power Treaty, which recognised Chinese sovereignty. As part of the agreements, Japan returned control of Shandong province to China, resolving the Shandong Problem[32]

In the years that followed (1922–1929), Britain, the United States, and Japan backed various Chinese warlords, often working against the revolutionary Nationalist government in Guangzhou (Canton). Britain and the U.S. supported Chen Jiongming's rebellion against the Nationalists, exacerbating tensions. These foreign interventions, and domestic instability, culminated in the Northern Expedition (1926–1927), which eventually brought most of China under Chiang Kai-shek’s control.[33]

On 30 May 1925, the killing of nine Chinese protesters by the British-led Shanghai Municipal Police triggered the 30 May Movement, a nationwide anti-British campaign. This incident highlighted growing Chinese resentment toward foreign imperialism.

Further unrest in Hankou (Wuhan) led to the Chen–O’Malley Agreement of 19 February 1927, under which Britain agreed to hand over its concession in Hankou to the Chinese authorities.

Between 1929 and 1931, China pursued full sovereignty by regaining control over its tariff rates, previously fixed at just 5% by foreign powers, and seeking to abolish extraterritorial privileges enjoyed by Britain and other nations in treaty ports like Shanghai. These goals were largely achieved by 1931.[34]

In 1930, Britain returned Weihai Harbour to Chinese control. Further diplomatic progress was marked by Britain's decision, on 17 May 1935, to elevate its Legation in Beijing to an Embassy; addressing longstanding Chinese complaints about the perceived disrespect of a lower diplomatic rank.[35]

Following the Chinese capital's move to Nanjing, the British Embassy also relocated there in 1936–1937. As Japan launched its invasion of China in 1937, British public opinion and government sympathy tilted in China's favour. Nonetheless, with Britain focused on defending its own empire, especially Singapore, direct support was limited. Britain did assist by training Chinese troops in India and providing airbases for American supply missions to China[36]

During World War II (1941–1945), Britain and China became official allies against Japan. Chinese troops trained in India fought alongside British forces in the Burma campaign. Close coordination continued throughout the war, symbolised by the wartime cooperation between Chiang Kai-shek and Winston Churchill. However, postwar diplomacy shifted dramatically. On 6 January 1950, His Majesty's Government withdrew its recognition from the Republic of China, now based in Taiwan, following the Communist victory on the mainland. Britain closed its Embassy in Nanjing but maintained a Consulate in Tamsui, nominally for liaison with the Taiwan Provincial Government.

Between the UK and the People's Republic of China (1949–present)

Between 1949 and the present, the relationship between the United Kingdom and the People's Republic of China (PRC) has evolved through a series of pragmatic decisions, diplomatic tensions, and significant historical moments.

During World War II, Britain was aligned with the anti-Communist Nationalist Chinese government. Following the war, British priorities centred on preserving stability in China to protect over £300 million in investments; far exceeding U.S. interests in the region. While Britain agreed not to interfere in Chinese affairs as per the 1945 Moscow Agreement, it remained sympathetic to the Nationalists, who appeared dominant in the Chinese Civil War until 1947.[37]

However, by August 1948, the tide had turned. With the Communists gaining ground, the British government began to prepare for their potential victory. It maintained consular operations in Communist-controlled areas and declined Nationalist appeals for British assistance in defending Shanghai. By December, Whitehall concluded that although nationalisation of British assets was likely, long-term economic engagement with a stable, industrialising China could prove beneficial. Safeguarding Hong Kong remained paramount, and the UK bolstered its garrison there in 1949, even as the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) offered reassurances on non-interference.

On 1 October 1949, the PRC government announced its willingness to establish diplomatic relations with any nation that severed ties with the Nationalists. After consultation with Commonwealth and European partners, Britain formally recognised the PRC in January 1950.[37]

On 20 April 1949, the People's Liberation Army attacked HMS Amethyst (F116) travelling to the British Embassy in Nanjing in the Amethyst incident. The CCP do not recognise the unequal treaties and protest the ship's right to sail on the Yangtze.[38][39]

Following recognition on 6 January 1950, the UK posted a chargé d'affaires in Beijing, expecting swift ambassadorial exchange. However, the PRC insisted on conditions concerning the Chinese seat at the United Nations and the handling of Nationalist-held foreign assets.

Meanwhile, British commercial interests began adapting to the new reality. In 1950, a consortium of British businesses formed the Group of 48 (now the China-Britain Business Council) to facilitate trade with the PRC.[35][40] This effort was further institutionalised with the formation of the Sino-British Trade Committee in 1954.

Military interactions between the two countries also occurred indirectly during the Korean War. British Commonwealth Forces engaged in several key battles against Chinese forces, including the defence of Hill 282 at Pakchon in 1950, clashes at the Imjin River in 1951, and successful engagements at Kapyong, Maryang San, and Yong Dong in 1953.

In a diplomatic breakthrough, a British Labour Party delegation led by Clement Attlee visited China in 1954 at the invitation of PRC Premier Zhou Enlai.[41] Attlee became the first high-ranking western politician to meet CCP Chairman Mao Zedong.[42] That same year, the Geneva Conference paved the way for mutual diplomatic presence: the PRC agreed to post a chargé d’affaires in London, reopen the British office in Shanghai, and issue exit visas for British nationals detained since 1951.[43] In 1961, the UK began to vote in the General Assembly for PRC membership of the United Nations. It had abstained on votes since 1950.[44]

During the Suez Crisis in 1956, China condemned the UK and France and made strong statements in support of Egypt.[45]: xxxvii

Bilateral relations soured during China's Cultural Revolution. In June 1967, Red Guards attacked British diplomats in Beijing, and PRC authorities offered no condemnation.[46]

Riots broke out in Hong Kong in June 1967. The commander of the Guangzhou Military Region, Huang Yongsheng, secretly suggested invading Hong Kong, but his plan was vetoed by PRC Premier Zhou Enlai.[47] That same month, unrest spread to Hong Kong, with PRC military commanders even contemplating an invasion; though Zhou Enlai vetoed the idea.[48] In July, Chinese troops fatally shot five Hong Kong police officers.

Hostilities escalated on 23 August 1967, when Red Guards stormed the British Office of the Chargé d'Affaires (predecessor body of British embassy) in Beijing, injuring chargé d'affaires Sir Donald Hopson and others, including Sir Percy Cradock. The attack was a reprisal for British arrests of CCP agents in Hong Kong. Days later, on 29 August, armed Chinese diplomats clashed with British police in London.[49]

A thaw began in March 1972, when the PRC extended full diplomatic recognition to the UK, allowing for ambassadorial exchange. The UK, in turn, acknowledged the PRC's position on Taiwan.[50]

In 1982, during negotiations over Hong Kong's future, Chinese paramount leader Deng Xiaoping bluntly told Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher that China could simply take the territory by force; later confirmed as a genuine consideration.[47] These talks culminated in the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration.

Queen Elizabeth II made a historic state visit to China in October 1986, becoming the first reigning British monarch to do so.[51]

The most symbolic moment in the bilateral relationship came on 30 June–1 July 1997, when Hong Kong was officially handed over from the United Kingdom to the People's Republic of China, marking the end of more than 150 years of British rule.

2000s

In the 2000s, significant developments shaped China–UK relations. On 29 October 2008, the United Kingdom formally recognised Tibet as an integral part of the People's Republic of China, marking a shift from its earlier position, which had only acknowledged Chinese suzerainty over the region.[52]

In November 2005, China and the UK signed a series of bilateral agreements, including announcing an initiative to jointly create "the world's first carbon neutral eco-city."[53]: 161 The contemplated development, Dongtan Eco-City, was not ultimately completed.[54]: 163–164 It later influenced other approaches to Chinese eco-cities.[54]: 163–164

Further strengthening bilateral ties, General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party and President Xi Jinping and Peng Liyuan paid a state visit to the UK from 20 to 23 October 2015. Their itinerary included stops in London and Manchester, with engagements involving Queen Elizabeth II and then-Prime Minister David Cameron. The visit culminated in the signing of trade deals valued at over £30 billion, symbolising deepening economic cooperation between the two nations.[55][56][57]

This spirit of engagement continued under Prime Minister Theresa May, who travelled to China in February 2018 for a three-day trade mission. During the visit, she met with Xi Jinping, affirming the continuation of what was described as the "Golden Era" in UK–China relations.[58]

Both countries share common membership of the G20, the UNSC P5, the United Nations, and the World Trade Organization. Bilaterally the two countries have a Double Taxation Agreement,[59] an Investment Agreement,[60] and the Sino-British Joint Declaration.

2020s

Throughout the 2020s, relations between China and the United Kingdom became increasingly strained, marked by disputes over human rights, national security, and espionage.

Tensions rose sharply in 2020 when the UK openly opposed China's imposition of the Hong Kong national security law. Lord Patten, the last British governor of Hong Kong, described the move as a breach of the "one country, two systems" framework and a violation of the Sino-British Joint Declaration.[61][62] Prime Minister Boris Johnson echoed this sentiment in Parliament, calling the law a "clear and serious breach" of the joint declaration. In response, the UK government announced a pathway to full British citizenship for around three million Hong Kong residents holding British National (Overseas) status.[63] That same year, the UK suspended its extradition treaty with China, citing concerns over the treatment of the Uyghur minority in Xinjiang.[64]

Also in 2020, citing security concerns, the UK government banned the use of Huawei's equipment in its 5G infrastructure.[65] The following year, the UK implemented a visa scheme for Hongkongers affected by the national security law, resulting in over 200,000 Hong Kong residents relocating to Britain.[66]

In April 2021, a cross-party group of MPs, led by Sir Iain Duncan Smith, passed a parliamentary motion declaring China's mass detention of Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang as genocide. This made the UK the fourth country globally to make such a declaration. In retaliation, China's embassy in London condemned the accusation as “the most preposterous lie of the century” and accused the UK of interfering in its internal affairs.[67]

UK-China relations were further tested in October 2022, when Chinese consulate officials in Manchester allegedly dragged a pro-democracy protester onto consulate grounds and assaulted him.[68] Six Chinese diplomats, including the consul-general, were subsequently recalled by Beijing.[69]

After becoming prime minister in July 2024, Keir Starmer signalled a tougher stance toward China, particularly regarding human rights abuses and China's support for Russia during its invasion of Ukraine.[70] However, diplomatic efforts to restore dialogue continued. In November 2024, Starmer met Chinese leader Xi Jinping at the G20 summit in an attempt to reset relations, balancing economic cooperation with national security concerns. The meeting was marred by an incident in which British journalists were forcibly removed by Chinese officials as Starmer raised human rights issues.[71][72]

In January 2025, UK Chancellor Rachel Reeves visited China in an effort to stabilise economic ties and normalise relations.[73] Yet friction persisted. In April 2025, the UK government introduced emergency legislation to prevent the closure of British Steel’s Scunthorpe plant by its Chinese owner, Jingye Group, citing national security reasons.[74][75] In a rare Saturday sitting, Parliament passed the law allowing the government to take control of the site, with Prime Minister Starmer framing the move as essential for national and economic security.[76][77] In May 2025, the National Health Service launched an investigation into breaches of two NHS hospitals targeted by Chinese state-linked hackers.[78] In September 2025, the Eastern Theater Command of the PLA accused Britain of "trouble-making and provocation" when it and the U.S. jointly sailed warships through the Taiwan Strait.[79]

In October 2025 the Director of Public Prosecutions controversially dropped charges under the Official Secrets Act 1911 against Christopher Cash and Christopher Berry. Cash had been a Parliamentary researcher for Alicia Kearns MP. He had also been director of the Conservative MP's China Research Group.[80]

In November 2025, it was reported that Sheffield Hallam University faced pressure from the Chinese government to halt research by Professor Laura Murphy on alleged forced labour of Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang. Threats to staff and restrictions on the university's websites in China aimed to protect access to Chinese students. After legal action and scrutiny, the university lifted the ban on the research in October 2025 and issued an apology, while UK authorities condemned foreign interference in academic freedom.[81]

In December 2025, Foreign Secretary Yvette Cooper identified China as a national security threat due to its cyber-attacks, espionage, and its support for Russia "in its war against Ukraine".[82]

Remove ads

Diplomacy

In 1954, UK Foreign Minister Anthony Eden and PRC Premier Zhou Enlai reached an agreement to exchange charges d'affaires.[83]: 93 As a result of the Korean War and other disagreements, the two countries did not exchange ambassadors until 1972.[83]: 93

|

|

Remove ads

Security concerns

Summarize

Perspective

British counter-terrorism authorities have reported a rise in hostile state activity linked to China within the United Kingdom, with operations allegedly involving threats to life such as planned attacks and covert actions. In July 2025, Dominic Murphy, head of London's Counter Terrorism Command, stated that the breadth, complexity, and volume of hostile operations from China among other countries had grown at a rate that neither British authorities, their international partners, nor the wider intelligence community had predicted. Officials also highlighted the increasing use of criminal proxies and vulnerable individuals, including minors, in carrying out these activities. Specific details regarding China's involvement were not disclosed.[84]

In July 2025, the UK Joint Committee on Human Rights labelled the China a "flagrant" perpetrator of transnational repression and presented a series of recommended responses to the UK government.[85]

Espionage

The government of the People's Republic of China (PRC) and various organs of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) have conducted surveillance and espionage in the United Kingdom, according to top UK national security officials such as the head of its domestic intelligence agency MI5.[86][87] UK officials, including experts at its MI5, have long been fearful that the PRC could shut down businesses in the nation with cyberattacks and spy equipment embedded in computer and telecommunications equipment.[88][89][90]

It is also been alleged that intelligence operatives from China might have been using platforms like LinkedIn to reach out to UK parliamentarians and conduct espionage.[91][92]

Academic freedom

Chinese intelligence agencies have threatened academic freedom at British universities. Sheffield Hallam University was threatened and pressured to stop the publication of research on Uyghur forced labor by Laura Murphy.[93][94][95]

Academics in British universities teaching on Chinese topics have been warned by the Chinese government to support the Chinese Communist Party or be refused entry to the country. Professors who disregarded the warnings to speak more positively about the CCP have had their visas cancelled which prevents them from doing fieldwork in China. Academics are warned to avoid the The Three Ts.[96] In March 2021, British Uyghur expert Joanne Smith Finley was sanctioned by China after she referred to the situation in Xinjiang as a genocide in comments given to the Associated Press.[97][98]

Remove ads

Transport

Summarize

Perspective

Air transport

All three major Chinese airlines, Air China, China Eastern & China Southern fly between the UK and China, principally between London-Heathrow and the three major air hubs of Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. China Southern also flies between Heathrow and Wuhan. Among China's other airlines; Hainan Airlines flies between Manchester and Beijing, Beijing Capital Airlines offers Heathrow to Qingdao, while Tianjin Airlines offers flights between Tianjin, Chongqing and Xi'an to London-Gatwick. Hong Kong's flag carrier Cathay Pacific also flies between Hong Kong to Heathrow, Gatwick and Manchester. The British flag carrier British Airways flies to just three destinations in China; Beijing, Shanghai and Hong Kong, and in the past Chengdu. Rival Virgin Atlantic flies between Heathrow to Shanghai and Hong Kong. British Airways has mentioned that it is interested in leasing China's new Comac C919 in its pool of aircraft of Boeing and Airbus.[99]

Rail transport

In January 2017, China Railways and DB Cargo launched the Yiwu-London Railway Line connecting the city of Yiwu and the London borough of Barking, and creating the longest railway freight line in the world. Hong Kong's MTR runs the London's TfL Rail service and has a 30% stake in South Western Railway. In 2017, train manufacturer CRRC won a contract to build 71 engineering wagons for London Underground. This is the first time a Chinese manufacturer has won a railway contract.[100]

Press

The weekly-published Europe edition of China Daily is available in a few newsagents in the UK, and on occasions a condensed version called China Watch is published in the Daily Telegraph.[101] The monthly NewsChina,[102] the North American English-language edition of China Newsweek (中国新闻周刊) is available in a few branches of WHSmith. Due to local censorship, British newspapers and magazines are not widely available in mainland China, however the Economist and Financial Times are available in Hong Kong.[citation needed]

Remove ads

British in China

Statesmen

- Sir Robert Hart was a Scots-Irish statesman who served the Chinese Imperial Government as Inspector General of Maritime Customs from 1863 to 1907.

- George Ernest Morrison resident correspondent of The Times, London, at Peking in 1897, and political adviser to the President of China from 1912 to 1920.

Diplomats

- Sir Thomas Wade – first professor of Chinese at Cambridge University

- Herbert Giles – second professor of Chinese at Cambridge University

- Harry Parkes

- Sir Claude MacDonald

- Sir Ernest Satow served as Minister in China, 1900–06.

- John Newell Jordan[103] followed Satow

- Sir Christopher Hum

- Augustus Raymond Margary

Merchants

Military

Missionaries

Academics

- Frederick W. Baller

- James Legge (first professor of Chinese at the University of Oxford)

- Joseph Needham

- Jonathan Spence

Remove ads

Chinese statesmen

- Li Hongzhang

- Zhang Zhidong

Cultural relations

Sports

Table tennis, originating from the United Kingdom, became one of the most iconic sports in China in the 20th century.[104]

In 2012, the Great Britain managed to beat China in the basketball olympics event with a score of 90-58, the first win for the host nation.

Public opinion

A survey published in 2025 by the Pew Research Center found that 56% of British people had an unfavorable view of China, while 39% had a favorable view. It also found that 56% of the people in the 18-35 age group had positive opinions of China.[105]

See also

- British Hong Kong (1841–1997)

- British Weihaiwei

- Foreign relations of the United Kingdom

- History of foreign relations of China

- China Policy Institute

- Foreign relations of China

- British Chinese (Chinese people in the UK)

- Sustainable Agriculture Innovation Network (between the UK and China)

References

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads