Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Anna Coleman Ladd

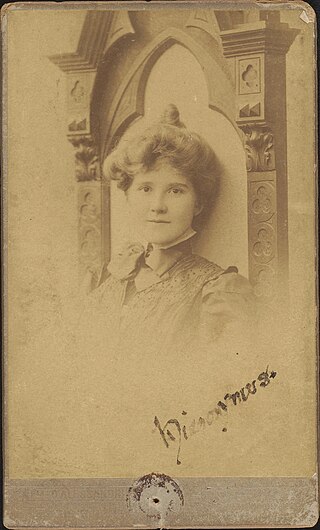

American sculptor (1878–1939) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Anna Coleman Watts Ladd (July 15, 1878 – June 3, 1939) was an American sculptor who traveled around the world in order to hone her skills. She is most well-known for her contributions to war efforts during World War I, but she was an accomplished sculptor, author, and playwright before the war began. She called many places home throughout her lifetime, including Pennsylvania, Boston, Rome, Paris, and California.

Remove ads

Biography

Summarize

Perspective

Anna Coleman Watts was born in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, on July 15th, 1878, to John and Mary Watts.[1] It is believed that she did not seek out formal training for the arts. Instead, she moved to Europe for 25 years, working in various studios[example needed]. On June 26th, 1905, she married Maynard Ladd, a physician, in Salisbury, England, and then moved to Boston.[1] Together, they had two daughters, Gabriella May Ladd and Vernon Abbott Ladd.

While in Boston, Ladd's husband was a faculty member at Harvard Medical School, specializing in pediatric diseases.[1] Meanwhile, Ladd focused on expanding her sculpting career while remaining the primary caretaker for both children.

In late 1917, her husband was appointed to direct the Children's Bureau of the American Red Cross in Toulouse. Ladd reluctantly stayed behind until she realized that her talents could be put to good use on the war front. She received permission and worked with the Red Cross to go to France to work in Paris's Masks for Facial Disfigurement Department.[2] There is no evidence that their two daughters were allowed to travel to Paris with them, likely staying behind in Boston.

In 1936, Ladd retired with her husband to Santa Barbara, California. On June 2nd, 1939, Ladd died from an undisclosed illness at sixty years old.[1] She was survived by her daughters, Gabriella May Ladd, the second wife of Henry Dwight Sedgwick (Kyra Sedgwick's paternal great-grandfather), and Vernon Abbott Ladd.

Remove ads

Art Outside of Wartime

Summarize

Perspective

There is no recollection of Ladd attending formal training for sculpture. However, while studying sculpture, she received feedback from recognizable sculpting artists, such as Ettore Ferrari (Rome), Emilio Gallori (Rome), Auguste Rodin (Paris), and Charles Grafly (Philadelphia).[1] She studied with Bela Pratt at the Boston Museum School upon her return to the United States.

Ladd wrote two books, The Joyous History of Hieronymus the Anonymous (1905), based on a medieval romance she worked on for years and The Candid Adventurer (1913), a sendup[definition needed] of Boston society. The Candid Adventurer tells the story of a painter who cannot see past superficial beauty.[3] The other protagonist feels as if she does not and cannot understand the struggles of those less fortunate than her. Unintentionally, this foreshadows Ladd's wartime experience. She also wrote two unproduced plays, one incorporating the story of a female sculptor who goes to war.

She devoted herself to portraiture[when?], and her work was well-regarded[by whom?].[citation needed] Her portrait of Eleanora Duse was one of only three the actress allowed.[citation needed]

After World War I, she depicted a decayed corpse on a barbed wire fence for a war memorial commissioned by the Manchester-by-the-Sea American Legion.

Remove ads

WWI and the Birth of Anaplastology

Anaplastology is defined as the combination of art and science, using design and engineering concepts to create removable prostheses, typically for the face and head.[4] World War I saw a dramatic expansion of the field, likely due to modern warfare weapons and techniques never used before.

Prosthetics work

Summarize

Perspective

Ladd stayed on the home front when her husband was sent to Paris; in her search for ways to help the war effort, she learned about the work of Francis Derwent Wood in London through C. Lewis Hind. Wood developed lifelike masks to help soldiers with facial deformities. Through correspondence with Wood, Ladd decided on a new process for creating masks using gutta-percha.[3] She applied for permission to go to France to work with the soldiers there but had to receive special permission from General John J. Pershing to do so, as it was forbidden for husbands and wives to serve in war zones at the same time.

Ladd founded the American Red Cross "Studio for Portrait-Masks" to provide cosmetic masks to be worn by men who had been badly disfigured in World War I. These men became collectively known as Gueules cassées.[3] As the importance of her work was recognized, she was able to obtain permission to create these cosmetic masks for disfigured soldiers living throughout France, rather than only Paris.[1]

Soldiers came to Ladd's studio to have a cast made of their face and their features sculpted onto clay or plasticine. Ladd would reference pre-injury photos of the soldiers to make masks as realistic as possible.[1] This form was then used to construct the prosthetic piece from extremely thin galvanized copper. The metal was painted with hard enamel to resemble the recipient's skin tone. Ladd used real hair to create the eyelashes, eyebrows, and mustaches. The prosthesis was attached to the face by strings or eyeglasses as the prosthetics created in Wood's "Tin Noses Shop" were.[2][5] When sculpting the masks, the lips were created to be slightly opened, to allow the victim to speak or smoke with relative ease.[1]

The masks were important because they provided soldiers with an opportunity to reintegrate into society without causing other civilians to stop and stare at them.[6] Ladd’s work is now called anaplastology. Anaplastology is the art, craft, and science of restoring absent or malformed anatomy artificially. Anaplastology, along with modern plastic surgery, was greatly shaped by World War I. It was during World War I that modern weapons and lack of protection for faces and skulls created a drastic increase in soldiers affected by facial disfigurement.[7]

Remove ads

Awards and Accomplishments

From 1907 to 1915, Ladd was the sole sculptor featured in multiple exhibitions, including exhibitions at The Gorham Gallery in New York (1913), the Corcoran Gallery in Washington D.C., and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.[1] Outside of these solo exhibitions, her works were featured at the Salon des Beaux-Arts (1913), the Art Institute of Chicago, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the National Academy of Design, and the National Sculpture Society.[1]

Her Triton Babies piece was shown at the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco. (It is now a fountain sculpture in the Boston Public Garden.) In 1914, she was founding member of the Guild of Boston Artists and exhibited in both the opening show and the traveling exhibition that followed. She later held a one-woman show at the Guild's gallery. She completed other works with mythological characters, and these pieces continue to surface and are sold in auctions today.[8] Her services earned her the Légion d'Honneur Croix de Chevalier and the Serbian Order of Saint Sava.[9] Her sculpture Triton Babies is featured on the Boston Women's Heritage Trail.[10]

Remove ads

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads