Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

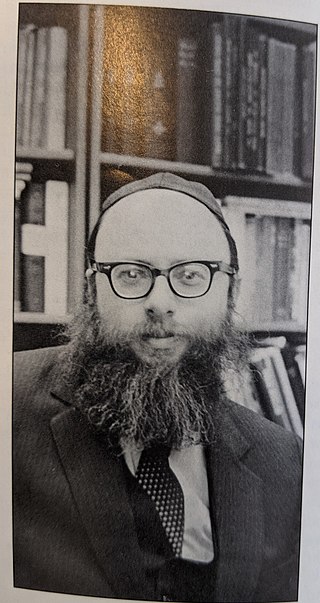

Aryeh Kaplan

American rabbi and physicist From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Aryeh Moshe Eliyahu Kaplan (Hebrew: אריה משה אליהו קפלן; October 23, 1934 – January 28, 1983)[1][2] was an American Orthodox rabbi, author, and translator best known for his Living Torah edition of the Torah and extensive Kabbalistic commentaries. He became well-known as a prolific writer and was lauded as an original thinker. His wide-ranging literary output, inclusive of introductory pamphlets on Jewish beliefs, and philosophy written at the request of NCSY are often regarded as significant factors in the growth of the baal teshuva movement.[3][4][5]

Remove ads

Early life

Summarize

Perspective

Aryeh Kaplan was born in the Bronx, New York City, to Samuel[6] and Fannie[7] (née Lackman) Kaplan[8][9] of the Sefardi Recanati family from Salonika, Greece.[2] His mother died on December 31, 1947, when he was 13, and his two younger sisters, Sandra and Barbara, were sent to a foster home. Kaplan was expelled from public school after acting out, leading him to grow up as a "street kid" in the Bronx.[10]

Kaplan did not grow up religious, and was known as "Len". His family had only a slight connection to Jewish practice, but he was encouraged to say Kaddish for his mother. On his first day at the minyan, Henoch Rosenberg, a 14-year-old Klausenburger Hosid, realized that Len was out of place—he was not wearing tefillin or opening a siddur—and befriended him. Henoch Rosenberg and his siblings taught Kaplan Hebrew, and within a few days, Kaplan was learning Chumash.[10]

When he was 15, Kaplan enrolled at Yeshiva Torah Vodaas, and at age 18 (from January 1953 until June 1953) was among "a small cadre of talmidim" selected to help Rabbi Simcha Wasserman open Yeshiva Ohr Elchonon, a new yeshiva in Los Angeles.[11]

After his time in Los Angeles, Kaplan had a few small jobs including teaching at a Hebrew school in the Bronx and at Beth Torah in Richmond, Virginia (February 1955).[12]

In January 1956, Kaplan went to Israel to study at the Mir in Jerusalem. That year, he received semikhah (rabbinic ordination) from some of Israel's foremost poskim, including Yitzhak HaLevi Herzog and Eliezer Yehuda Finkel.[13]

Remove ads

Secular career

Upon returning from Israel in August of 1956, Kaplan became a Hebrew teacher at Eliahu Academy in Louisville, Kentucky.[14] and beginning in the 1957 fall semester studied at University of Louisville, where he joined Sigma Pi Sigma, the Woodcock Society, and Phi Kappa Phi and eventually completed his bachelor's degree in physics on June 11, 1961.[15] While in Louisville, he met Tobie Goldstein, whom he married on June 13, 1961, and with whom he had nine children.[9][16]

Kaplan then moved to Hyattsville, Maryland, in 1961 to study physics at the University of Maryland and begin his first professional position as a research scientist at the National Bureau of Standards's Fluid Mechanics Division, where he was in charge of magnetohydrodynamics research. Kaplan earned his M.S. degree in physics from University of Maryland in 1963.[9] After graduating, Kaplan remained at University of Maryland as a National Science Foundation fellow[17] through the fall semester of 1964.[18][19][9]

Remove ads

Rabbinic career

Summarize

Perspective

In 1965, Kaplan switched careers and began practicing as a rabbi. In his book Encounters, Kaplan wrote that when asked why he switched from his scientific career to the rabbinate, he said "God had a mission for me".[20] His career here divides between pulpit roles initially, and other roles thereafter when based in Brooklyn, New York. Kaplan is mentioned in Igros Moshe: he asked of and received a response from Moshe Feinstein regarding the matter of permitting/enabling a youth minyan to which parents would drive children on Shabbos.[21]

Pulpit roles

- Adas Israel (1965–1966): On February 19, 1965, Kaplan moved to Mason City, Iowa, where he became the Rabbi of Adas Israel.[22][23] According to a February 1965 article, "Because of his teaching and study since ordination, this is Rabbi Kaplan's first pulpit."[12]

- B'nai Sholom (1966–1967): On August 7, 1966, Kaplan became the Rabbi at B'nai Sholom, a Conservative synagogue[24] in Blountville, Tennessee. He held the position through 1967.[25][26]

- Adath Israel (1967–1969): In 1967, Kaplan became the Rabbi at Adath Israel (now known as Adath Shalom), a Conservative synagogue in Dover, New Jersey. He kept this position through 1969.[9]

- Ohav Shalom (1969–1971): Kaplan then moved to Albany, New York, where he became the Rabbi at Ohav Shalom, a Conservative synagogue.[27] During this time, he also functioned as the president of the AJCC (Albany Jewish Community Center) and the Hillel Counselor to the B'nai B'rith Hillel Counselorship at University at Albany, SUNY.[9][28][29][30]

Brooklyn

In 1971 Kaplan moved to Brooklyn, New York, where he lived until the end of his life (1983) .[9] Kaplan did not hold any positions there as a pulpit rabbi, but had many other roles which involved, chiefly, writing and editing religious publications:[9]

- Chaplain at Hunter and Baruch colleges (New York), from 1971 to 1972

- Associate Editor of "Intercom", of the Association of Orthodox Jewish Scientists, from 1972 to 1973

- Editor of Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations of America's Jewish Life magazine from 1973 to 1974[31]

- Director of publishing at the NCSY from 1974 to 1975.

In the 1970s, Kaplan served in the unofficial capacity of the spiritual advisor for NCSY's Brooklyn region. He would converse with teenagers and answer their questions, whether in his home or at drawn-out NCSY conventions where "Aryeh Kaplan was the last adult standing."[3]

He would also deliver lectures at his home in Kensington, which many locals would regularly attend.[3]

He also served as the rabbinic consultant for the play "Yentl", after the director met him on the Staten Island Ferry. When asked about his association with a play containing nudity and a woman dressed as a man, Kaplan was quoted to have said "It is an abomination, but so what?"[32]

Remove ads

NCSY

Summarize

Perspective

Kaplan was involved with NCSY as an author, speaker, and spiritual mentor.

Pinchas Stolper's wrote in his introduction to The Aryeh Kaplan Anthology how he "discovered" Kaplan:[2]

I first encountered this extraordinary individual when by chance I spotted his article on "Immortality in the Soul" in "Intercom," the journal of the Association of Orthodox Jewish Scientists, and was taken by his unusual ability to explain a difficult topic - one usually reserved for advanced scholars, a topic almost untouched previously in English - with such simplicity that it could be understood by any intelligent reader. It was clear to me that his special talent could fill a significant void in English Judaica. I always counted as one of my greatest z'chusim (a spiritual merit granted by God) to have had the privilege of "discovering" Rabbi Kaplan. And once we met, we became lifelong friends. When I invited Rabbi Kaplan to write on the concept of Tefillin for the Orthodox Union's National Conference of Synagogue Youth (NCSY), he completed the 96-page manuscript of God, Man and Tefillin with sources and footnotes from the Talmud, Midrash and Zohar - in less than 2 weeks. The book - masterful, comprehensive, inspiring yet simple - set a pattern which was to characterize all of his succeeding works.

Remove ads

Breslov

Summarize

Perspective

Kaplan became involved with Breslov through Rabbi Zvi Aryeh Rosenfeld. In 1973, Rabbi Kaplan translated "Rebbe Nachman’s Wisdom", one of Breslov's most important works, into English on Rabbi Zvi Rosenfeld's request.[33] Kaplan also translated and annotated two other books: Until the Mashiach: The Life of Rabbi Nachman, a day-to-day account of Rebbe Nachman's life, and Rabbi Nachman's Tikkun (based on the Tikkun HaKlali).

Kaplan was also involved in preserving Rabbi Nachman of Breslov's grave. In 1979, the government in Uman was planning on demolishing the cemetery containing Rabbi Nachman's grave so they could build housing over it. Rabbis Michel Dorfman and Noson Maimon of Breslov contacted Rabbi Moshe Sherer of Agudath Israel of America, who connected them with Rabbi Pinchas Teitz, who then introduced them to Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan. "Using a manual typewriter, Kaplan put together a presentation there on the spot with maps of Ukraine to show exact longitude and latitude". Rabbi Teitz then sent the presentation to Robert Lipshutz and less than two weeks later after Jimmy Carter met with Leonid Brezhnev at the Strategic Arms Limitation Conference in Vienna, the Soviet ambassador to the U.S. stated that "the Kremlin has decided to honor the plan as originally scheduled, except for Bilinsky Street. That yard will remain untouched." and it was declared an "international shrine."[34][35][36][37][38]

Remove ads

Literary output

Summarize

Perspective

Kaplan produced works on topics as varied as prayer, Jewish marriage and meditation. His writing incorporated ideas from across the spectrum of Rabbinic literature, Kabbalah,[39] and Hasidut, all without ignoring science.[40][41][42] The concise and detail-orientated character of his works have been described as reflective of his physicist training.[43] In researching his books, Kaplan once remarked "I use my physics background to analyze and systematize data, very much as a physicist would deal with physical reality."[44]

From 1976 onward, Kaplan worked to translate Me'am Lo'ez (Torah Anthology), which was originally written in Ladino and in time edited for Hebrew (1967). Kaplan was described as working with his typewriter, "the Me’am Loez in Ladino on one side of him and the Hebrew version on the other side, and he'd look from one to the other and back again, comparing and contrasting and typing away furiously the entire time."[3] Shortly before his death, he completed The Living Torah, an original translation of the Five Books of Moses and the Haftarot.

Kaplan was described by Rabbi Pinchas Stolper, his original sponsor, as never fearing to speak his mind. "He saw harmony between science and Judaism, where many others saw otherwise. He put forward creative and original ideas and hypotheses, all the time anchoring them in classical works of rabbinic literature."[citation needed]

Remove ads

Death

Kaplan died at his home of a heart attack on January 28, 1983, at the age of 48.[16] He was buried at the Mount of Olives Jewish Cemetery in Jerusalem.[45]

Legacy

Kaplan's Living Torah was posthumously followed by a work written by others for the rest of the Bible, The Living Nach (published in 3 volumes in the 1990s).

His works continue to be read, and his extensive references are used as a resource.[46]

His works have been translated into Czech, French, Hungarian, Modern Hebrew, Portuguese, Russian, German and Spanish.

In 2021, NCSY republished Kaplan's works.[47]

The Aryeh Kaplan Academy day school in Louisville, Kentucky, is named in honor of Kaplan.[48]

Remove ads

Bibliography

Summarize

Perspective

Religious works

- The Living Torah, Rabbi Kaplan's best-known work, is a translation into English of the Torah, and one of the first to be structured around the parshiyot (the traditional division of the Torah text). It includes maps and diagrams, and incorporated research on realia, flora, fauna, and geography (here, drawing on sources as varied as Josephus, Dio Cassius, Philostratus and Herodotus). The work features frequent footnotes, which also indicate differences in interpretation amongst the commentators, classic and modern.[49] Rabbi Kaplan called this book his 10th child, since it took him exactly nine months to complete.[3] (Moznaim, 1981, ISBN 0-940118-35-1)

- "The Handbook of Jewish Thought," produced early in his career, is a wide-ranging treatment of Judaism's fundamental beliefs[50] in two volumes, the first of which was published in Kaplan's lifetime.[51] A chapter titled "Creation,"[52] in which Rabbi Kaplan "presents evolution as part of the basic tenets of Judaism,"[53] was omitted from publication.[54]

- "Torah Anthology," a 45-volume translation of Me'am Lo'ez from Ladino (Judæo-Spanish) into English. Rabbi Kaplan was the primary translator.

- "Made in Heaven: A Jewish Wedding Guide" (Moznaim, ISBN 978-0940118119)

- "Tefillin: God, Man and Tefillin"; "Love Means Reaching Out"; "Maimonides' Principles"; "The Fundamentals of Jewish Faith"; "The Waters of Eden: The Mystery of the Mikvah"; "Jerusalem: Eye of the Universe" — a series of highly popular and influential booklets on aspects of Jewish philosophy and various religious practices. Published by the Orthodox Union/NCSY[44] or as an anthology by Artscroll, 1991, ISBN 1-57819-468-7.

- Five booklets of the Young Israel Intercollegiate Hashkafa Series — "Belief in God"; "Free Will and the Purpose of Creation"; "The Jew"; "Love and the Commandments"; and "The Structure of Jewish Law" launched his writing career. He was also a frequent contributor to The Jewish Observer. (These articles have been published as a collection: Artscroll, 1986, ISBN 0-89906-173-7)

- "The Real Messiah? A Jewish Response to Missionaries" at the Wayback Machine (archived May 29, 2008).

- Sichot HaRan ("Rabbi Nachman's Wisdom"), edited by Rabbi Zvi Aryeh Rosenfeld who had requested Kaplan translate this.[33] Kaplan also translated and annotated Until the Mashiach: The Life of Rabbi Nachman, a day-to-day account of Rebbe Nachman's life, for the Breslov Research Institute. In conjunction with Rosenfeld, Kaplan translated and annotated Rabbi Nachman's Tikkun (based on the Tikkun HaKlali).

- Kaplan translated and annotated classic works on Jewish mysticism — Sefer Yetzirah, Bahir, and Derekh Hashem — as well as produced much original work on the subject in English. His Moreh Ohr, a Hebrew-language work, discusses the purpose of Creation, tzimtzum and free will from a kabbalistic point of view.

- "If You Were God," his final work, was published posthumously in 1983. It encourages the reader to ponder topics concerning the nature of being and Divine providence.[55]

Release dates

Academic papers

While a graduate student studying physics at the University of Maryland, Rabbi Kaplan published two academic papers:

- Oneda, S.; Kim, Y.S.; Kaplan, L.M. (1964). "Final-state interactions in η 0 → 3π decay". Il Nuovo Cimento. 34 (3): 655–664. Bibcode:1964NCim...34..655O. doi:10.1007/BF02750008. S2CID 121217695. Archived from the original on March 16, 2016.

- Kaplan, L.M.; Resnikoff, M. (November 1967). "Matrix Products and the Explicit 3, 6, 9, and 12-j Coefficients of the Regular Representation of SU(n)". Journal of Mathematical Physics. 8 (11): 2194–2205. Bibcode:1967JMP.....8.2194K. doi:10.1063/1.1705141. Archived from the original on 2013-04-11.

Remove ads

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads