Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Autoclave

Pressurised heating apparatus From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

An autoclave is a machine used to carry out industrial and scientific processes requiring elevated temperature and pressure in relation to ambient pressure and temperature. Autoclaves are found in many medical settings, laboratories, and other places that need to ensure the sterility of an object.

The autoclave was invented by Charles Chamberland in 1879,[1] although a precursor known as the steam digester was created by Denis Papin in 1679.[2] The name comes from Greek auto-, meaning "self", and Latin clavis meaning "key", thus a self-locking device.[3] All autoclaves operate according to the same fundamental principles as a kitchen pressure cooker. The simplest autoclaves (so-called "stovetop autoclaves") are largely indistinguishable from pressure cookers used in food preparation.

Autoclaves are most commonly used before surgical procedures to sterilize medical instruments and supplies. This is accomplished by subjecting these items to pressurized saturated steam at 121 °C (250 °F) at a gauge pressure of 15 pounds per square inch (100 kPa; 1.0 atm)[4][5] for 15 to 60 minutes (or longer), depending on the size, density, and contents of the load.[6]

Industrial autoclaves are used in industrial applications, especially in the manufacturing of composites. Autoclaves are also commonly used in the chemical industry to cure coatings, vulcanize rubber, and for hydrothermal synthesis. Flexible "research-grade" autoclaves are used in a wide range of research and industrial tasks, including quality control and quality assurance for food and beverage production, biomedical and pharmaceutical research and development, and product testing.[7][8]

Remove ads

Uses

Summarize

Perspective

Sterilization autoclaves are widely used in microbiology and mycology, medicine and prosthetics fabrication, tattooing and body piercing, and funerary practice, and a wide range of industries (including food production). Autoclaves vary in size and function depending on the media to be sterilized. They are sometimes called retorts in the chemical and food industries (in the latter case this is short for "canning retorts"). Typical loads include laboratory glassware, growth media, other equipment, surgical instruments, and potentially pathogenic waste.[9]

A notable recent and increasingly popular application of autoclaves is the pre-disposal treatment and sterilization of waste material, such as pathogenic medical waste. Machines in this category largely operate under the same principles as conventional autoclaves in that they are able to neutralize (but not eliminate) potentially infectious agents by using pressurized steam and superheated water.[10] A thermal effluent decontamination system functions as a single-purpose autoclave designed for the sterilization of liquid waste and effluent.

Autoclaves are also widely used to cure composites, especially for melding multiple layers without any voids that would decrease material strength (as is the case in producing laminated glass[11]), and in the vulcanization of rubber[12]. The high heat and pressure that autoclaves generate help to ensure that the best possible physical properties are repeatable. Manufacturers of spars for sailboats have autoclaves well over 50 feet (15 m) long and 10 feet (3 m) wide, and some autoclaves in the aerospace industry are large enough to hold whole airplane fuselages made of layered composites.[13]

Remove ads

Air removal

Summarize

Perspective

It is very important to ensure that all of the trapped air is removed from the load prior to beginning the sterilization cycle, as trapped air is a very poor medium for achieving sterility. Steam at 134 °C (273 °F) can achieve a desired level of sterility in three minutes, while achieving the same level of sterility in hot air requires two hours at 160 °C (320 °F).[14] Methods of air removal include:

- Downward displacement (or gravity-type):

- As steam enters the chamber, it fills the upper areas first as it is less dense than air. This process compresses the air to the bottom, forcing it out through a drain which often contains a temperature sensor. Only when air evacuation is complete does the discharge stop. Flow is usually controlled by a steam trap or a solenoid valve, but bleed holes are sometimes used. As the steam and air mix, it is also possible to force out the mixture from locations in the chamber other than the bottom.

- Steam pulsing:

- Air dilution by using a series of steam pulses, in which the chamber is alternately pressurized and then depressurized to near atmospheric pressure.

- Vacuum pumps:

- A vacuum pump sucks air or air/steam mixtures from the chamber. Vacuum pumps have been shown to improve sterilization reliability in steam autoclaves by 90% or more.[15]

- Superatmospheric cycles:

- Achieved with a vacuum pump. It starts with a vacuum followed by a steam pulse followed by a vacuum followed by a steam pulse. The number of pulses depends on the particular autoclave and cycle chosen.

- Subatmospheric cycles:

- Similar to the superatmospheric cycles, but chamber pressure never exceeds atmospheric pressure until they pressurize up to the sterilizing temperature.

Stovetop autoclaves used in poorer or non-medical settings rarely have automatic air removal programs. The operator is required to manually perform steam pulsing at certain pressures as indicated by the gauge.[16]

Remove ads

In medicine

Summarize

Perspective

A medical autoclave is a device that uses steam to sterilize equipment and other objects. This means that all bacteria, viruses, fungi, and spores are inactivated.[17] However, prions, such as those associated with Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, and some toxins released by certain bacteria, such as Cereulide, may not be destroyed by autoclaving at the typical 134 °C for three minutes or 121 °C for 15 minutes and instead should be immersed in sodium hydroxide (1M NaOH) and heated in a gravity displacement autoclave at 121 °C for 30 min, cleaned, rinsed in water and subjected to routine sterilization.[18] Although a wide range of archaea species, including Geogemma barossii (Strain 121), can survive and even reproduce at temperatures found in autoclaves, their growth rate is so slow at the lower temperatures in the less extreme environments occupied by humans that it is unlikely they could compete with other organisms.[19] None of them are known to be infectious or otherwise pose a health risk to humans. Their biochemistry is so different from that of humans, and their multiplication rate is so slow, that microbiologists need not worry about them.[20]

Because damp heat is used, heat-labile products (such as some plastics) cannot be sterilized this way or they will melt. Paper and other products that may be damaged by steam must also be sterilized another way. In all autoclaves, items should always be separated to allow the steam to penetrate the load evenly.

Many procedures today employ single-use items rather than sterilizable, reusable items. This first happened with hypodermic needles, but today many surgical instruments (such as forceps, needle holders, and scalpel handles) are commonly single-use rather than reusable items (see waste autoclave).

Autoclaving is often used to sterilize medical waste prior to disposal in the standard municipal solid waste stream. This application has become more common as an alternative to incineration due to environmental and health concerns about the combustion by-products emitted by incinerators, especially from the small units which were commonly operated at individual hospitals. Incineration or a similar thermal oxidation process is still often mandated for pathological waste and other very toxic or infectious medical waste. For liquid waste, an effluent decontamination system is the equivalent hardware.

In most of the industrialized world medical-grade autoclaves are regulated medical devices. Many medical-grade autoclaves are therefore limited to running regulator-approved cycles. Because they are optimized for continuous hospital use, they favor rectangular designs, require demanding maintenance regimens, and are costly to operate. (A properly calibrated medical-grade autoclave uses thousands of gallons of water each day, independent of task, with correspondingly high electric power consumption.)

Remove ads

In research

Summarize

Perspective

Autoclaves are used research and education to sterilize lab instruments and glassware, process waste loads prior to disposal, prepare culture media and liquid media, and artificially age materials for testing. They play a prominent role in biomedical research, pharmaceutical research, and industrial R&D. Research autoclaves display a wide range of designs and sizes, and may be tailored to their use and load type. Common variations include either a cylindrical or square pressure chamber, air- or water-cooling systems, air-ballast systems (to prevent burst containers or boil-over when sterilizing liquids), and vertically or horizontally opening chamber doors (which may be electrically or manually powered). Research-grade autoclaves may be configured for "pass-through" operation. This makes it possible to maintain absolute isolation between "clean" and potentially contaminated work areas. Pass-through research autoclaves are especially important in BSL-3 or BSL-4 facilities.

Autoclaves not intended for use in a medical setting may be referred to as "research-grade" autoclaves. These are specifically designed for non-medical applications. Research autoclaves use a “jacketless” design where steam is generated directly in the pressure chamber using heating coils (rather than relying on a “steam jacket” and independent steam generator, as is the case in high-throughput medical autoclaves). Research-grade autoclaves do not have to meet stringent requirements associated with sterilizing instruments that will be directly used on humans. Instead they can prioritize efficiency, programming flexibility, ease-of-use, and sustainability.[21]

The added cost of using a medical autoclave in a non-medical setting can be significant. For a 2016 study, the Office of Sustainability at the University of California, Riverside (UCR) tracked the power and water consumption of medical-grade and research-grade autoclaves performing similar research-related tasks. Even when functioning within intended parameters, the medical-grade autoclaves consumed 700 gallons of water and 90 kWh of electricity per day (1,134MWh of electricity and 8.8 million gallons of water per year). UCR's research-grade autoclaves performed the same tasks with equal effectiveness, but used 83% less energy and 97% less water.[22] The University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) completed a similar study in 2023 comparing similar-sized jacketed (i.e., "medical") and non-jacketed (i.e., "research") autoclaves performing identical cycles indicative of the most common load and sterilization tasks used by their researchers. UAB found that jacketed autoclaves consumed significantly more water (44–50 gallons per cycle) and house steam (25–41 pounds per cycle) than non-jacketed autoclaves, which used less than 2 gallons of water and no house steam per cycle. The higher water use by jacketed autoclaves resulted in an estimated water cost of $764 per jacketed autoclave per year, compared to $23 for non-jacketed autoclaves. With over 100 steam-jacketed autoclaves on campus, the author calculated that using jacketed autoclaves for research tasks translated into an additional $74,000 in annual excess spending for UAB. Jacketed autoclaves also had a higher initial purchase price (37% more than non-jacketed equivalents).[23]

Remove ads

Quality assurance

Summarize

Perspective

In order to sterilize items effectively, it is important to use optimal parameters when running an autoclave cycle. A 2017 study performed by the Johns Hopkins Hospital biocontainment unit tested the ability of pass-through autoclaves to decontaminate loads of simulated biomedical waste when run on the factory default setting. The study found that 18 of 18 (100%) mock patient loads (6 PPE, 6 linen, and 6 liquid loads) passed sterilization tests with the optimized parameters compared to only 3 of 19 (16%) mock loads that passed with use of the factory default settings.[24]

There are physical, chemical, and biological indicators that can be used to ensure that an autoclave reaches the correct temperature for the correct amount of time. If a non-treated or improperly treated item can be confused with a treated item, then there is the risk that they will be mixed up, which is critical in areas such as surgery.

Chemical indicators on medical packaging and autoclave tape change color once the correct conditions have been met, indicating that the object inside the package, or under the tape, has been appropriately processed. Autoclave tape is only a marker that steam and heat have activated the dye. The marker on the tape does not indicate complete sterility. A more difficult challenge device, named the Bowie-Dick device after its inventors, is also used to verify a full cycle. This contains a full sheet of chemical indicator placed in the center of a stack of paper. It is designed specifically to prove that the process achieved full temperature and time required for a normal minimum cycle of 134°C for 3.5–4 minutes.[25]

To prove sterility, biological indicators are used. Biological indicators contain spores of a heat-resistant bacterium, Geobacillus stearothermophilus. If the autoclave does not reach the right temperature, the spores will germinate when incubated and their metabolism will change the color of a pH-sensitive chemical. Some physical indicators consist of an alloy designed to melt only after being subjected to a given temperature for the relevant holding time. If the alloy melts, the change will be visible.[26]

Some computer-controlled autoclaves use an F0 (F-nought) value to control the sterilization cycle. F0 values are set for the number of minutes of sterilization equivalent to 121 °C (250 °F) at 103 kPa (14.9 psi) above atmospheric pressure for 15 minutes. Since exact temperature control is difficult, the temperature is monitored, and the sterilization time adjusted accordingly.[citation needed]

Remove ads

Additional images

- Stovetop autoclaves, also known as pressure cooker—the simplest of autoclaves

- The machine on the right is an autoclave used for processing substantial quantities of laboratory equipment prior to reuse, and infectious material prior to disposal. (The machines on the left and in the middle are washing machines.)

- Horizontal high-capacity autoclave with cylindrical chamber

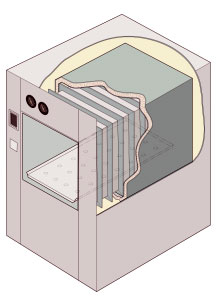

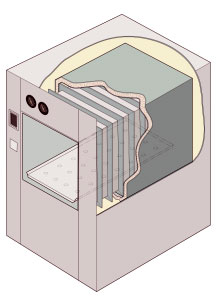

- Illustration of a cylindrical-chamber pass-through autoclave

Remove ads

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads