Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Benedict Pereira

Spanish theologian and philosopher (1536–1610) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Benedict Pereira (also Pereyra, Benet Perera, Benet Pererius) (March 4, 1536 – 6 March 1610) was a Spanish Jesuit philosopher, theologian, and exegete.

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (May 2014) |

Life

Pereira was born at Ruzafa, near Valencia, in Spain. He entered the Society of Jesus in 1552 and taught successively literature, philosophy, theology, and sacred scripture in Rome, where he died.

Works

Summarize

Perspective

He published eight works, and left a vast deal of manuscript. (Sommervogel, infra, mentions twelve sets.)

His main philosophical work is De communibus omnium rerum naturalium principiis et affectionibus libri quindecim (Rome, 1576).

The main difficulties of the Book of Genesis are met in Commentariorum et disputationum in Genesim tomi quattuor (Rome, 1591–1599). This is a mine of information in regard to the Deluge, Noah's Ark, the Tower of Babel, etc., and was highly rated by Richard Simon (Histoire critique du Vieux Testament, III, xii).

The Commentariorum in Danielem prophetam libri sexdecim (Rome, 1587) are much less diffuse.

Other writings published by Pereira were:

- 137 exegetical dissertations in five volumes on "Exodus" (Ingolstadt, 1601)

- 188 dissertations on "The Epistle to the Romans" (Ingolstadt, 1603);

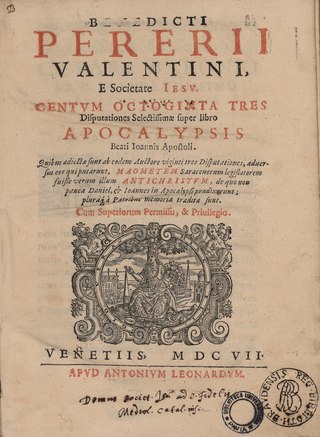

- 183 dissertations on "The Apocalypse"

- 214 dissertations on "The Gospel of St. John", chapters 1 through 9 (Lyons, 1608)

- 144 dissertations on "The Gospel of St. John", chapters 10 through 14 (Lyons, 1610)

To the fourth volume of the dissertations is appended a work of twenty-three dissertations to show that Mohammed was not the Antichrist, of the Apocalypse and of Daniel.

Remove ads

Debate against Clavius

Pereira was an outspoken opponent of Christopher Clavius at the Collegio Romano.[1] The debate concerned the nature of mathematics. Pereira argued that mathematical demonstrations point to complex relations between numbers, lines, figures, etc., but lack the logical force of a demonstration from true causes or the essence of things. Furthermore, mathematics does not have a true subject matter; it merely draws connections between different properties (Alexander, p. 69). Clavius responded in "Prolegomena" that the subject of mathematics is matter itself, since all mathematics is "immersed" in matter. The debate had broad ramifications with regard to inclusion of mathematics as a basic subject in the Jesuit curriculum.

References

Bibliography

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads