Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Bertram Windle

British scientist, educationalist and writer From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Sir Bertram Coghill Alan Windle, FRS, FSA, KSG (8 May 1858 – 14 February 1929) was a British anatomist, administrator, archaeologist, scientist, educationalist and writer.[1][2]

Remove ads

Biography

Summarize

Perspective

He was born at Mayfield Vicarage, in Staffordshire, where his father, the Reverend Samuel Allen Windle, a Church of England clergyman, was vicar.[3] He attended Trinity College, where he graduated B.A. in 1879. He also served as Librarian of the University Philosophical Society in the 1877–78 session.

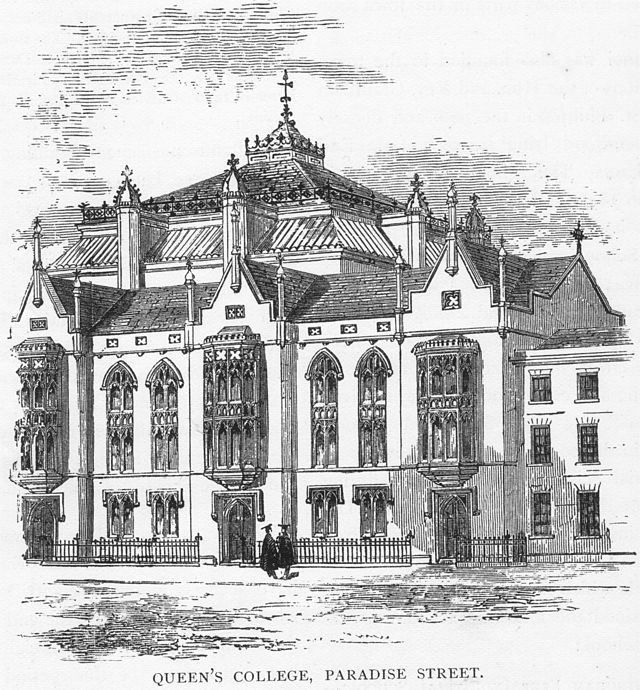

In 1891 he was appointed dean of the medical faculty of Queen's College, Birmingham. Queen's College's medical faculty became the medical faculty of Mason Science College in the early 1890s, and then became the medical faculty of the University of Birmingham in 1900. Windle was professor of anatomy and anthropology and first Dean of the Medical Faculty at Birmingham University. He was a member of the Teachers′ Registration Council until he resigned in late 1902.[4] In 1904 he accepted the presidency of Queen's College, Cork.[5] He acted as president of the university (which became known as University College Cork in 1908) until 1918, when he moved to Canada.[6]

During Windle’s time as president of University College Cork, he worked with John Robert O’Connell on the Honan Bequest which resulted in the building of the Honan Chapel with the inclusion of stained glass windows by An Túr Gloine and by Harry Clarke.

During his medical training days, Windle was an atheist. He later converted to Catholicism.[7] He was a critic of Darwinism and took influence from St. George Jackson Mivart.[7][8] Historian David N. Livingstone has noted that Windle favoured a Catholic version of neo-Lamarckism.[9]

Windle was a vitalist.[10] Historian Peter J. Bowler has written that Windle was "one of the few biologists to defend an outright vitalism."[11]

Remove ads

Family

Windle married twice, first in 1886 to Madoline Hudson, and in 1901 to Edith Mary Nazer. He died in 1929 aged 71.[12][13]

Honours

Windle was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1899.[14] In 1909, he was made a knight of St. Gregory the Great by Pius X. In 1912, he was made a Knight Bachelor and therefore granted the title sir.[15] He was knighted by King George V during a ceremony at Buckingham Palace on 6 March 1912.[16]

Works

Summarize

Perspective

- A Collection of Archaeological Pamphlets on Roman Remains (1878).

- Congenital Malformations and Heredity (1888).

- The Birmingham School of Medicine (1890).

- The Proportions of the Human Body (1892).

- The Modern University (1892).

- A Philological Essay Concerning the Pygmies of the Ancients (1894)

- A Handbook of Surface Anatomy and Landmarks (1896).

- Life in Early Britain (1897).

- Shakespeare's Country (1899).

- Vitalism and Scholasticism (1900).

- The Malvern Country (1901).

- The Wessex of Thomas Hardy (1902).

- Chester (1904).

- Remains of the Prehistoric Age in England (1904).

- What is Life? A Study of Vitalism and Neo-Vitalism (1908).

- Facts and Theories (1912).

- A Century of Scientific Thought and Other Essays (1915).

- The Church and Science (1917).[17]

- Science and Morals and other Essays (1919).

- The Romans in Britain (1923).

- On Miracles and Some Other Matters (1924).

- Who's Who of the Oxford Movement (1926).

- Evolution and Catholicity (1926).

- The Catholic Church and its Reactions with Science (1927).

- The Evolutionary Problem as it is Today (1927).

- Religions Past and Present (1928; 1st Pub. 1927).

- History as it is Taught (1928).

Selected articles

- "Totemism and Exogamy," The Dublin Review (1911).

- "The National University and Development of the Intellectuality of the Nation," Journal of the Ivernian Society (1911).

- "Nicolaus Stensen." In: Twelve Catholic Men of Science (1912).

- "Thomas Dwight." In: Twelve Catholic Men of Science (1912).

- "Darwin and the Theory of Natural Selection," The Dublin Review (1912).

- "The National University and the People", Journal of the Ivernian Society (1912).

- "A Great Catholic Scientist: Joseph Van Beneden (1809–1894)," The Catholic World (1912–1913).

- "Early Man," The Dublin Review (1913).

- "Some Recent Works on the Antiquity of Man," Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review (1914).

- "The Latest Gospel of Science," Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review (1915).

- "Miracles—Fifty Years Ago and Now", The Catholic World (1915).

- "Prehistoric Art in Europe," The Dublin Review (1917).

- "Science in 'Bondage'," The Catholic World (1917).

- "The Irish Convention: A Member's Afterthoughts," The Living Age (1918).

- "A Medical View of Miracles," The Catholic World (1919–1920).

- "From the Dark Ages," The Catholic World (1921).

- "Astrology," The Catholic World (1922).

- "Science Sees the Light," Commonweal (1924).

- "Scott and the Oxford Movement," Commonweal (1924).

- "Huxley and the Catholic Church," Commonweal (1925).

- "Europe in the Age of Stone and Bronze." In: Universal World History (1937).

Miscellany

- "Recent Developments in University Education in Great Britain," (1921).

- Introduction to the 1906 edition of The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne, by Gilbert White (1720–93).

Remove ads

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads