Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Bibliotheca Historica

World history written by Diodorus Siculus From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Bibliotheca Historica (Latin; Greek: Βιβλιοθήκη Ἱστορική, Bibliothḗkē Historikḗ), also known as the Historical Library[1] or Library of History,[2] is a work of universal history by Diodorus Siculus. It consisted of forty books, which were divided into three sections. The first six books are geographical in theme and describe the history and culture of Egypt (Book I), of Mesopotamia, India, Scythia, and Arabia (II), of North Africa (III), and of Greece and Europe (IV–VI). In the next ten books, he recounts human history starting with the Trojan War (Book VII) down to the death of Alexander the Great (XVII). The final section concerns the historical events from the successors of Alexander (Book XVIII) down to the time of the First Triumvirate of the late Roman Republic (XL). The end of the work has been lost, and it is unclear whether Diodorus actually reached the beginning of Caesar's Gallic War in 59 BC (as he promises at the beginning of the work) or, as evidence suggests, he stopped short at 60 BC owing to old age and weariness from his labors. He selected the name "Library" as an acknowledgement that he was assembling a composite work drawing from many sources. Of the authors he used, some who have been identified include Hecataeus of Abdera, Ctesias of Cnidus, Ephorus, Theopompus, Hieronymus of Cardia, Duris of Samos, Diyllus, Philistus, Timaeus, Polybius, and Posidonius.

Diodorus's immense work has not survived intact. Only Books I–V and Books XI–XX remain in their entirety. The rest exists only in fragments preserved in Photius and in the Excerpta of Constantine Porphyrogenitus.

Remove ads

Dating

Summarize

Perspective

The earliest date Diodorus mentions of his own labors is his visit to Egypt during the 180th Olympiad (60–56 BC). This visit was marked by his witnessing an angry mob demand the death of a Roman citizen who had accidentally killed a cat, an animal sacred to the ancient Egyptians.[3] The latest contemporary event Diodorus mentions is Octavian's vengeance on the city of Tauromenium, whose refusal to help him led to Octavian's naval defeat nearby in 36 BC.[4] Diodorus shows no knowledge that Egypt became a Roman province—which transpired in 30 BC—so presumably he published his completed work before that event. Diodorus asserts that he undertook a number of dangerous journeys through Europe and Asia during his historical research and devoted thirty years to the composition of his history,[5] suggesting his work was began around the 70s BC.[6]

One notable feature of Diodorus's writing is his tendency to provide unfulfilled cross-references, times where he includes notes similar to "we will cover this matter later in the work" or "see book X" but the topic is never addressed again in the surviving text. Catherine Rubicam suggests this is evidence of the author's change in temporal scope away from current events.[6] In his preface, Diodorus writes that he will conclude with "the beginning of the war between the Romans and the Celts" in 58 BC.[5] However, elsewhere he mentions Caesar's 55 BC invastion of Britain and subsequent 44 BC deification.[7]

Remove ads

Structure

Summarize

Perspective

In the Bibliotheca Historica, Diodorus sets out to write a universal history, covering the entire world and all periods of time up to his present day. Each book opens with a table of its contents and a preface discussing the relevance of history, issues in the writing of history, or the significance of the events discussed in that book. These are now generally agreed to be entirely Diodorus's own work.[8] The degree to which the text that follows is derived from earlier historical works is debated.

The first five books describe the history and culture of different regions, without attempting to determine the relative chronology of events. Diodorus expresses serious doubts that such chronology is possible for "barbarian" lands and the distant past. The resulting books have affinities with the genre of geography. Books VI to X, which covered the transition from mythical times to the archaic period, are almost entirely lost. By Book X, Diodorus had taken up an annalistic structure,[9] narrating all the events throughout the world in each year before moving on to the next one. Books XI–XX, which are completely intact and cover events between 480 and 302 BC, maintain this annalistic structure. Books XI–XL, which brought the work down to Diodorus's own lifetime and terminated around 60 BC, are mostly lost.[10]

Book I: Egypt

Book I opens with a prologue on the work as a whole, arguing for the importance of history generally and universal history in particular. The rest of the book is devoted to Egypt and is divided into two halves. In the first half he covers the origin of the world and the development of civilization in Egypt. A long discussion of the theories offered by different Greek scholars to explain the annual floods of the River Nile serves to showcase Diodorus's wide reading. In the second half of the book, he presents the history of Egypt, its customs and religion, in a highly respectful tone. His main sources are believed to have been Hecataeus of Abdera and Agatharchides of Cnidus.[11]

Book II: Asia

This book has only a short prologue outlining its contents. The majority of the book is devoted to the history of the Assyrians, focused on the mythical conquests of Ninus and Semiramis, the fall of the dynasty under the effeminate Sardanapallus, and the origins of the Medes who overthrew them.[12] This section is explicitly derived from the account of Ctesias of Cnidus.[13] The rest of the book is devoted to describing the various other peoples of Asia. He first describes India,[14] drawing on Megasthenes,[15] then the Scythians of the Eurasian steppe, including the Amazons and the Hyperboreans,[16] and Arabia Felix.[17] He finishes the book with Iambulus's description of the "Islands of the Sun" in the Indian Ocean,[18] presented as a traveller's account but seeming to be a Hellenistic utopian fiction.

Book III: Africa

In this book, Diodorus describes the geography of Northern Africa and Arabia including Ethiopia, Egypt's gold mines, the Persian Gulf, and Libya, where he sites mythical figures including the Gorgons, Amazons, Ammon, and Atlas. Based on the writings on Agatharchides, Diodorus describes the horrible conditions of the Egyptian mines:

... those who have been condemned in this way—and they are a great multitude and are all bound in chains—work at their task unceasingly both by day and throughout the entire night... For no leniency or respite of any kind is given to any man who is sick, or maimed, or aged, or in the case of a woman for her weakness, but all without exception are compelled by blows to persevere in their labours, until through ill-treatment they die in the midst of their tortures.[19]

Book IV: Mythic Greece

In this book, Diodorus describes the mythology of Greece. He narrates the myths of Dionysus, Priapus, the Muses, Heracles, Jason and the Argonauts, Medea, the hero Theseus, and the Seven against Thebes.

Book V: Europe

In this book, Diodorus describes the geography of Europe. He covers the islands of Sicily, Malta, Corsica, Sardinia, and the Balearic Islands. He then covers Britain, "Basilea", Gaul, the Iberian peninsula, and the regions of Liguria and Tyrrhenia on the Italian peninsula. Finally he describes the islands of Hiera and the utopian Panchaea in the "Southern Ocean" and the Greek islands.

Books VI–X: Trojan War and Archaic Greece

Books VI–X survive only in fragments, which cover mythic and legendary events before and after the Trojan War including the stories of Bellerophon, Orpheus, Aeneas, and Romulus; some history from cities including Rome and Cyrene; tales of kings such as Croesus and Cyrus the Great; and discussion of philosophers such as Pythagoras and Zeno.

Book XI: 480–451 BC

This book has no prologue, just a brief statement of its contents.

The main focus of the book are events in mainland Greece, principally the Second Persian invasion of Greece under Xerxes,[20] Themistocles's construction of the Peiraeus and Long Walls and his defection to Persia,[21] and the Pentecontaetia.[22] Interwoven through these accounts are descriptions of events in Sicily, focusing on Gelon of Syracuse's war with the Carthaginians,[23] his Deinomenid successors' prosperity and fall,[24] and the Syracusans' war with Ducetius.[25]

Diodorus's source for his account of mainland Greece in this book is generally agreed to be Ephorus of Cyme, but some scholars further argue that Diodorus likely supplemented Ephorus with accounts from Herodotus, Thucydides, and others.[26]

Book XII: 450–416 BC

The book's prologue muses on the mutability of fortune. Diodorus notes that bad events can have positive outcomes, like the prosperity of Greece which (he felt) resulted from the Persian Wars.

Diodorus's account mostly focuses on mainland Greece, covering the end of the Pentecontaetia,[27] the first half of the Peloponnesian War,[28] and conflicts during the Peace of Nicias.[29] Most of the side narratives concern events in central and southern Italy, particularly the foundation of Thurii[30] and the secession of the Plebs in Rome.[31] An account of the war between Leontini and Syracuse, culminating in the embassy of Gorgias to Athens,[32] sets up the account of the Sicilian Expedition in Book XIII.

Diodorus is believed to have continued to use Ephorus, perhaps supplemented with other historians, as his source for Greek events in this book, while the source for the events in western Greece is usually identified as Timaeus of Tauromenium.[33]

Book XIII: 415–404 BC

Diodorus explains that, given the amount of material to be covered, his prologue must be brief.

This book opens with the account of the Sicilian Expedition, culminating in two very long speeches at Syracuse deliberating about how to treat the Athenian prisoners.[34] After that the two areas again diverge, with the Greek narrative covering the Decelean War down to the battles of Arginusae and Aigospotami.[35] The Sicilian narrative recounts the beginning of the Second Carthaginian War, culminating with the rise of Dionysius the Elder to the tyranny.[36]

Ephorus is generally agreed to have continued to be the source of the Greek narrative and Timaeus of the Sicilian narrative. The source of the Sicilian expedition is disputed: Both Ephorus and Timaeus have been put forward.[37] Kenneth Sacks argues that the two speeches ending the account are Diodorus's own work.[38]

Book XIV: 404–387 BC

In the prologue, Diodorus identifies reproachful criticism (blasphemia) as the punishment for evil deeds which people most take to heart and which the powerful are especially subject to. Powerful men, therefore, should avoid evil deeds in order to avoid receiving this reproach from posterity. Diodorus claims that the central subjects of the book are negative examples, demonstrating the truth of his remarks.

The book is again mostly divided into Greek and Sicilian narratives. The Greek narrative covers the Thirty Tyrants of Athens,[39] the establishment and souring of Spartan hegemony over Greece,[40] Cyrus the Younger's attempt to seize the Persian throne with the aid of the Ten Thousand,[41] Agesilaus's invasion of Persian Asia Minor,[42] and the Boeotian War.[43] The Sicilian narrative focuses on Dionysios the Elder's establishment of his rule over eastern Sicily,[44] his second war with the Magonid Carthaginians,[45] and his invasion of southern Italy.[46] Fairly brief notes cover Roman affairs year by year, including the war with Veii[47] and the Gallic Sack.[48]

Ephorus and Timaeus are assumed to have still been Diodorus's main sources.[49] Some details in his account of the Ten Thousand may derive from a lost work of Sophaenetus.[50]

Book XV: 386–361 BC

In the prologue of this book, Diodorus makes several statements that have been considered important for understanding the philosophy behind his entire work. Firstly, he announces the importance of speaking freely (parrhesia) for the overall moral goal of his work, insofar as he expects his frank praise of good figures and criticism of bad ones to encourage his readers to behave morally. Secondly, he declares that the fall of the Spartan Empire, which is described in this book, was caused by their cruel treatment of their subjects. Sacks considers this idea about the fall of empires to be a core theme of Diodorus's work, motivated by his own experience as a subject of Rome.[51]

This book covers the height of the Spartan rule in Greece, including the invasion of Persia, the Olynthian War, and the occupation of Thebes's Cadmea,[52] as well as the Spartan defeat in the Boeotian War which resulted in the rise of the Theban Hegemony.[53] The main side narratives are Evagoras's war with the Persians on Cyprus,[54] the wars of Dionysius I against the Illyrians, Etruscans, and Carthaginians and his death,[55] Artaxerxes II's failed invasion of Egypt,[56] the Scytalism in Argos,[57] the career of Jason of Pherae,[58] and the Great Satraps' Revolt.[59]

Diodorus's main source is generally believed to have been Ephorus, but—possibly through him—he also seems to have drawn on other sources, like the Hellenica Oxyrhynchia.[60] It is disputed whether he continued using Timaeus of Tauromenium for his description of Sicilian affairs in this book or if this too was based on Ephorus.[61]

Book XVI: 360–336 BC

The Prologue announces the importance of cohesion within narratives: A book or chapter should, if possible, narrate an entire story from start to finish.

It then praises Philip II of Macedonia, whose involvement in the Third Sacred War and resulting rise are the main subjects of the book. The principal side narratives are Dion of Syracuse's overthrow of Dionysius II,[62] the Romans' Social War,[63] Artaxerxes III's reconquest of Egypt,[64] and the expedition of Timoleon.[65]

The initial sources for the main narrative was probably Ephorus, but his account came to an end in 356 BC and Diodorus's sources after that point are disputed. Possibilities include Demophilus, Diyllus, Duris of Samos, and Theopompus. Contradictions in his account suggest that he was following multiple sources simultaneously and was unable to reconcile their narratives.[66] The Sicilian material probably draws on Timaeus and also cites Athanis.[67]

Book XVII: 335–324 BC

This book covers Alexander the Great from his accession to his conquests and his death in Babylon. Despite a promise in the brief prologue to discuss other contemporary events, it does not contain any side-narratives, although—unlike other accounts of Alexander—it does mention Antipater's activities in Greece during Alexander's absence. Owing to its length, the book is split into two halves, the first running down to the Battle of Gaugamela[68] and the second part continuing until Alexander's death.[69]

Diodorus's sources for the story of Alexander are much debated. Sources of information include Aristobulus of Cassandreia, Cleitarchus, Onesicritus, and Nearchus, but it is not clear that he used these directly.[70] Several scholars have argued that the unity of this account implies a single source, perhaps Cleitarchus.[71]

Book XVIII: 323–318 BC

This book covers the years 323–318 BC, describing the disputes which arose between Alexander's generals after his death and the beginning of the Wars of the Diadochoi. The account is largely based on Hieronymus of Cardia.[72] There is no discussion of events outside the eastern Mediterranean, although cross-references at other points indicate that Diodorus intended to discuss Sicilian affairs.

Book XIX: 317–311 BC

This book opens with a prologue arguing that democracy is usually overthrown by the most powerful members of society, not the weakest, and advancing Agathocles of Syracuse as a demonstration of this proposition.

The narrative of the book continues the account of the Diadochi, recounting the Second and Third Wars of the Diadochi. The Babylonian War is completely unmentioned. Interwoven in this narrative is the rise to power of Agathocles of Syracuse and the beginning of his war with Carthage. It is disputed whether this latter narrative strand is based on Callias of Syracuse, Timaeus of Tauromenium, or Duris of Samos.

Book XX: 310–302 BC

The prologue of this book discusses Greek historians' practice of inventing speeches for their characters to deliver. Diodorus criticizes the practice as inappropriate to the genre, but acknowledges that in moderation such speeches can add variety and serve a didactic purpose.

The book is devoted to two parallel narratives, one describing Agathocles's ultimately unsuccessful invasion of Carthage's homelands in North Africa and the other devoted to the continued wars of the Diadochi, particularly the campaigns of Antigonus Monophthalmus and Demetrius Poliorcetes. The only significant side narrative is the account of Cleonymus of Sparta's wars in Italy.[73]

Books XXI–XL

These books do not survive intact, but large sections were preserved by Byzantine compilers working under Constantine VII and by epitomists like Photius. They covered the history of the Hellenistic kingdoms from the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC, the Punic Wars, and the events of the late Roman Republic down to either 60 BC or the beginning of Caesar's Gallic War in 59 BC. Book XXXII is notable for the inclusion of the lives of Diophantus of Abae, Callon of Epidaurus, and others who transitioned between genders. The record of Callon's medical treatment is the first known account of gender-affirming surgery.[74]

For Books XXI–XXXII, Diodorus drew on the Histories of Polybius, which largely survives and can be compared against Diodorus's text, though he may also have also used Philinus of Agrigentum and other lost historians. Books XXXII–XXXVIII or XXXIX probably had Poseidonius as their source.[75]

Remove ads

Reception

Summarize

Perspective

Ancient

Diodorus is mentioned briefly in Pliny the Elder's Natural History as being singular among the Greek historians for the simple manner in which he named his work.[76]

Modern

Diodorus's liberal use of earlier historians underlies the harsh opinion of the author of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article on the Bibliotheca Historica:[77]

The faults of Diodorus arise partly from the nature of the undertaking, and the awkward form of annals into which he has thrown the historical portion of his narrative. He shows none of the critical faculties of the historian, merely setting down a number of unconnected details. His narrative contains frequent repetitions and contradictions, is without colouring, and monotonous; and his simple diction, which stands intermediate between pure Attic and the colloquial Greek of his time, enables us to detect in the narrative the undigested fragments of the materials which he employed.

As biased as this sounds, other more recent classical scholars are likely to go even further. Diodorus has become infamous particularly for adapting his tales ad maiorem Graecorum gloriam ("to the greater glory of the Greeks"),[where?] leading one prominent author[who?] to refer to him as one of the "two most accomplished liars of antiquity" (the other being Ctesias).[78][79]

Far more sympathetic is the estimate of Charles Henry Oldfather, who wrote in the introduction to his translation of Diodorus:[80]

While characteristics such as these exclude Diodorus from a place among the abler historians of the ancient world, there is every reason to believe that he used the best sources and that he reproduced them faithfully. His First Book, which deals almost exclusively with Egypt, is the fullest literary account of the history and customs of that country after Herodotus. Books II–V cover a wide range, and because of their inclusion of much mythological material are of much less value. In the period from 480 to 301 BC, which he treats in annalistic fashion and in which his main source was the Universal History of Ephorus, his importance varies according to whether he is the sole continuous source, or again as he is paralleled by superior writers. To the fifty years from 480 to 430 BC Thucydides devotes only a little more than thirty chapters; Diodorus covers it more fully (11.37–12.38) and his is the only consecutive literary account for the chronology of the period. ... For the years 362–302 BC Diodorus is again the only consecutive literary account, and ... Diodorus offers the only chronological survey of the period of Philip, and supplements the writers mentioned and contemporary sources in many matters. For the period of the Successors to Alexander, 323–302 BC (Books XVIII–XX), he is the chief literary authority and his history of this period assumes, therefore, an importance which it does not possess for the other years.

Remove ads

Editorial history

Summarize

Perspective

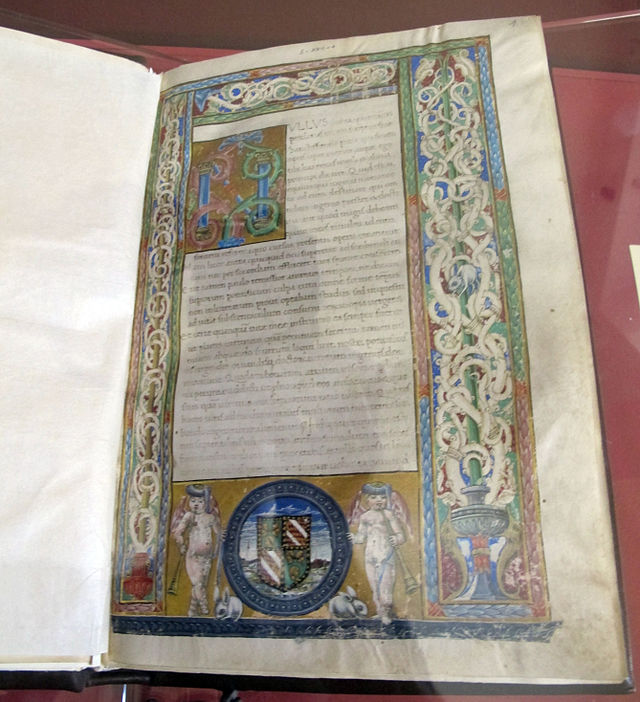

The earliest extant manuscript of Bibliotheca Historica is from around the 10th century.[81] The editio princeps of Diodorus was a 1449 Latin translation of the first five books by Poggio Bracciolini[82] printed with an edition of Tacitus's Germania at Bologna in 1472.[83] (This edition claimed to produce Books I–VI, Bracchiolini having split Diodorus's own Book I into two parts at Chapter 42.)[84] The first printing of the Greek original—by Vincent Obsopoeus at Basel in 1539—contained only Books XVI to XX.[85] It was not until 1559 that all of the surviving books and the surviving fragments from Book XXI to the end were published by Stephanus at Geneva.[86]

Manuscripts

A total of 59 medieval manuscripts exist for Books I–V and/or XI–XX of the Bibliotheca Historica. A complete set including the now lost Books VI–X and XI–XL existed in the Great Palace of Constantinople until its sack in 1453.[87] For Books I–V, all medieval manuscripts descend from four independent prototypes according to Bertrac and Vernière:[88]

Remove ads

Editions and translations

Greek

- Obsopoeus, Vincent, ed. (1539), Diodōrou Sikeliōtou Historiōn Biblia Tina Διοδωρου Σικελιωτου Ιστοριων Βιβλια Τινα [Certain Books of Diodorus of Sicily's History], Basel: Johannes Oporinus.

- Stephanus, Henricus, ed. (1559), Diodōrou tou Sikeliōtou Bibliothēkēs Istorikēs Bibloi Pentekaideka ek tōn Tessarakonta Διοδωρου του Σικελιωτου Βιβλιοθηκης Ιστορικης Βιβλοι Πεντεκαιδεκα εκ των Τεσσαρακοντα [Fifteen of the Forty Books of Diodorus of Sicily's Historical Library], Geneva: Ulricus Fugger.

Latin

- Diodori Siculi Historiarum Priscarum [Diodorus of Sicily's Books of Ancient History], translated by Poggio Bracciolini, 1449,[84] manuscript copied numerously, printed as Diodori Siculi Historiarum Priscarum, Bologna: Baldassare Azzoguidi, 1472, republished numerously.

- Sordi, Marta, ed. (1969). Diodori Siculi Bibliothecae Liber Sextus Decimus [The Sixteenth Book of Diodorus of Sicily's Library]. Biblioteca di Studi Superiori, No. 56. Florence: La Nuova Italia.

English

- Diodori Siculi Historiarum Priscarum a Poggio Etc [Diodorus of Sicily's Books of Ancient History Translated by Poggius Etc], translated by John Skelton, c. 1485,[91] manuscript held as CCCC MS 357.

- The Historical Library of Diodorus the Sicilian in Fifteen Books... to Which are Added the Fragments of Diodorus that Are Found in the Bibliotheca of Photius Together with Those Publish'd by H. Valesius, L. Rhodomannus, and F. Ursinus, translated by George Booth, London: Edward Jones, John Churchill, & Edward Castle, 1700.

- Diodorus of Sicily, Loeb Classical Library, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1933–1967.

- Diodorus of Sicily, Vol. I: Books I and II, 1–34, LCL 279, translated by Charles Henry Oldfather, 1933, ISBN 978-0-674-99307-5

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help). - Diodorus of Sicily, Vol. II: Books II (Continued) 35 – IV, 58, LCL 303, translated by Charles Henry Oldfather, 1935, ISBN 978-0-674-99334-1

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help). - Diodorus of Sicily, Vol. III: Books IV (Continued) 59 – VIII, LCL 340, translated by Charles Henry Oldfather, 1939, ISBN 978-0-674-99375-4

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help). - Diodorus of Sicily, Vol. IV: Books IX – XII, 40, LCL 375, translated by Charles Henry Oldfather, 1946, ISBN 978-0-674-99413-3

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help). - Diodorus of Sicily, Vol. V: Books XII 41 – XIII, LCL 384, translated by Charles Henry Oldfather, 1950, ISBN 978-0-674-99422-5

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help). - Diodorus of Sicily, Vol. VI: Books XIV – XV, 19, LCL 399, translated by Charles Henry Oldfather, 1954, ISBN 978-0-674-99439-3

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help). - Diodorus of Sicily, Vol. VII: Books XV. 20 – XVI. 65, LCL 389, translated by Charles Lawton Sherman, 1952, ISBN 978-0-674-99428-7

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help). - Diodorus of Sicily, Vol. VIII: Books XVI. 66–95 and XVII, LCL 422, translated by Charles Bradford Welles, 1963, ISBN 978-0-674-99464-5

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help). - Diodorus of Sicily, Vol. IX: Books XVIII and XIX 1–65, LCL 377, translated by Russel Mortimer Geer, 1947, ISBN 978-0-674-99415-7

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help). - Diodorus of Sicily, Vol. X: Books XIX. 66–110 and XX, LCL 390, translated by Russel Mortimer Geer, 1954, ISBN 978-0-674-99429-4

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help). - Diodorus of Sicily, Vol. XI: Fragments of Books XXI–XXXII, LCL 409, translated by Francis Redding Walton, 1957, ISBN 978-0-674-99450-8

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help). - Diodorus of Sicily, Vol. XII: Fragments of Books XXIII–XL, LCL 423, translated by Francis Redding Walton, 1967, ISBN 978-0-674-99465-2.

- Diodorus of Sicily, Vol. I: Books I and II, 1–34, LCL 279, translated by Charles Henry Oldfather, 1933, ISBN 978-0-674-99307-5

- Diodorus Siculus, Books 11–12.37.1: Greek History, 480–431 BC: The Alternative Version, translated by Peter Green, Austin: University of Texas Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0-292-71277-5.

- Diodorus Siculus, The Persian Wars to the Fall of Athens: Books 11–14.34 (480–401 BCE), translated by Peter Green, Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0-292-72125-8.

- The Library, Books 16–20: Philip II, Alexander the Great, and the Successors, translated by Robin Waterfield, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019, ISBN 9780198759881.

French

- Bibliothèque historique, Collection Budé (various editors & translators, 1993–2018), Tome I: Introduction générale. Livre I; Tome II: Livre II; Tome III: Livre III; Tome IV: Fragments, Livres XXXIII–XL; Tome V: Livre V, Livre des îles; Tome VI: Livre XI; Tome VII: Livre XII; Tome IX: Livre XIV; Tome X: Livre XV; Tome XI: Livre XVI; Tome XII: Livre XVII; Tome XIII: Livre XVIII; Tome XIV: Livre XIX; and Tome XV: Livre XX.

Remove ads

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads