Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Berlin Blockade

USSR blockade of Berlin, 1948–1949 From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The Berlin Blockade (24 June 1948 – 12 May 1949) was one of the first major international crises of the Cold War. During the multinational occupation of post–World War II Germany, the Soviet Union blocked the Western Allies' railway, road, and canal access to the sectors of Berlin under Western control. The Soviets offered to drop the blockade if the Western Allies withdrew the newly introduced Deutsche Mark from West Berlin.

The Western Allies organised the Berlin Airlift (German: Berliner Luftbrücke, lit. "Berlin Air Bridge") from 26 June 1948 to 30 September 1949 to carry supplies to the people of West Berlin, a difficult feat given the size of the city and the population.[1][2] American and British air forces flew over Berlin more than 250,000 times, dropping necessities such as fuel and food, with the original plan being to lift 3,475 tons[clarification needed] of supplies daily.[citation needed] By the spring of 1949, that number was often met twofold, with the peak daily delivery totalling 12,941 tons.[3] Among these was the work of the later concurrent Operation Little Vittles in which candy-dropping aircraft dubbed "raisin bombers" generated much goodwill among German children.[4]

Having initially concluded there was no way the airlift could work, the Soviets found its continued success an increasing embarrassment.[citation needed] On 12 May 1949, the USSR lifted the blockade of West Berlin, due to economic issues in East Berlin, although for a time the Americans and British continued to supply the city by air as they were worried that the Soviets would resume the blockade and were only trying to disrupt Western supply lines. The Berlin Airlift officially ended on 30 September 1949 after fifteen months. The US Air Force had delivered 1,783,573 tons (76.4% of total) and the RAF 541,937 tons (23.3% of total),[nb 1] totalling 2,334,374 tons, nearly two-thirds of which was coal, on 278,228 flights to Berlin. In addition Canadian, Australian, New Zealand and South African air crews assisted the RAF during the blockade.[5]: 338 The French also conducted flights, but only to provide supplies for their military garrison.[6]

American C-47 and C-54 transport airplanes, together, flew over 92,000,000 miles (148,000,000 km) in the process, almost the distance from Earth to the Sun.[7] British transports, including Handley Page Haltons and Short Sunderlands, flew as well. At the height of the airlift, one plane reached West Berlin every thirty seconds.[8]

Seventeen American and eight British aircraft crashed during the operation.[9] A total of 101 fatalities were recorded as a result of the operation, including 40 Britons and 31 Americans,[8] mostly due to non-flying accidents.

The Berlin Blockade served to highlight the competing ideological and economic visions for postwar Europe. It played a major role in aligning West Berlin with the United States and Britain as the major protecting powers,[10] and in drawing West Germany into the NATO orbit several years later in 1955.

Remove ads

Background (1945 – mid-1948)

Summarize

Perspective

Potsdam Agreement and division of Berlin

From 17 July to 2 August 1945, the victorious Allies reached the Potsdam Agreement on the fate of postwar Europe, calling for the division of defeated Germany, west of the Oder-Neisse line, into four temporary occupation zones each one controlled by one of the four occupying Allied powers: the United States, the United Kingdom, France and the Soviet Union (thus re-affirming principles laid out earlier by the Yalta Conference). These zones were located roughly around the then-current locations of the allied armies.[11] All four zones would be treated as single economic unit through the Allied Control Council (consisting of the military governors of each zone) located in Berlin.[12] Berlin was also divided into four occupation zones, despite the city's location, 100 miles (160 km) inside Soviet-controlled eastern Germany. The United States, United Kingdom, and France controlled western portions of the city, while Soviet troops controlled the eastern sector.[11]

Each military governor had ultimate authority in his zone which meant the Allied Control Council had to have unanimous agreement.[12] The Allied Western powers never explicitly agreed with the Soviet Union that they had right of access to Berlin. There was only a verbal agreement between Marshal Georgi K. Zhukov, the Soviet commander in Germany, General Lucius D. Clay, Commander in Chief, United States Forces in Europe, and Sir Robert Weeks, representative of the British government.[13] On 30 November 1945, the Allied Control Council in Berlin approved the only written agreement regarding transportation to Berlin from the West. This gave allowance for three 20-mile-wide air corridors between the city and West Germany for French, British and American planes. Also stipulated in the agreement was for Berlin airspace to be controlled by a four-power Air Safety Centre.[13]

In the eastern zone, the Soviet authorities forcibly unified the Communist Party of Germany and Social Democratic Party (SPD) in the Socialist Unity Party ("SED"), claiming at the time that it would not have a Marxist–Leninist or Soviet orientation.[14] The SED leaders then called for the "establishment of an anti-fascist, democratic regime, a parliamentary democratic republic" while the Soviet Military Administration suppressed all other political activities.[15] Factories, equipment, technicians, managers and skilled personnel were removed to the Soviet Union.[16]

Growing Tensions (1945–1947)

In a June 1945 meeting, Stalin informed German communist leaders that he expected to slowly undermine the British position within their occupation zone, that the United States would withdraw within a year or two and that nothing would then stand in the way of a united Germany under communist control within the Soviet orbit.[17] Stalin and other leaders told visiting Bulgarian and Yugoslavian delegations in early 1946 that Germany must be both Soviet and communist.[17]

Berlin quickly became the focal point of both US and Soviet efforts to re-align Europe to their respective visions. As Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov noted, "What happens to Berlin, happens to Germany; what happens to Germany, happens to Europe."[18] Berlin had suffered enormous damage; its prewar population of 4.3 million people was reduced to 2.8 million.

After harsh treatment, forced emigration, political repression and the particularly harsh winter of 1945–1946, Germans in the Soviet-controlled zone were hostile to Soviet endeavours.[17] Local elections in 1946 resulted in a massive anti-communist protest vote, especially in the Soviet sector of Berlin.[17] Berlin's citizens overwhelmingly elected non-Communist members to its city government.[19]

The Soviets also granted only three air corridors for access to Berlin from Hamburg, Bückeburg, and Frankfurt.[20] In 1946 the Soviets stopped delivering agricultural goods from their zone in eastern Germany, and the American commander, Lucius D. Clay, responded by stopping shipments of dismantled industries from western Germany to the Soviet Union. In response, the Soviets started a public relations campaign against American policy and began to obstruct the administrative work of all four zones of occupation.

Marshall Plan and Soviet reaction

Futher information: The Marshall Plan

American planners had privately decided during the war that it would need a strong, allied Germany to assist in the rebuilding of the West European economy.[21] In January 1947, James F. Byrnes resigned as Secretary of State and was succeeded by George C. Marshall who was tasked with consolidating power in Western Germany.[12] President Truman was concerned about the influence of Stalin in spreading communism to other European countries. Truman adopted a policy of containment and part of this plan involved giving significant amounts of money to capitalist Western European countries. [citation needed] The delivery of aid was called the European Recovery Program, also known as the Marshall Plan, after General C. Marshall, and was introduced in June 1947.

To coordinate the economies of the British and United States occupation zones, these were combined on 1 January 1947 into what was referred to as the Bizone.[17] At a meeting of the Council of Foreign Ministers, in November–December 1947, in London, the allies could not agree among themselves to reunite Germany.[12] Britain and America discussed how to move forward, and Bevin and Marshall had their Military Governors in Germany to coordinate a political structure in Bizonia. (In July 1949, the French zone is merged into the Bizone, thus forming the Trizone)

Soviet propaganda warned against America, for example, a poster from 1947 shows a Soviet soldier holding a history of the Great Patriot War book, warning Uncle Sam to "stop messing around".[19] An article by Yuliana Semyonova in Pravda on 12 June 1947 said that America's geopolitical strategy was fascist. [citation needed] The Soviet Writers Union held a meeting that June and condemned writers who "kowtowed to the West".[19] On July 31, 1947, the Central Committee directs the newspaper Literaturnaya Gazeta to criticise and target American way of life. [citation needed]

Remove ads

Immediate Causes (early 1948)

Summarize

Perspective

London Six-Power Conference (1948)

Trilateral talks were held in London, between the UK, US, France and the Benelux nations, met twice in London (London 6-Power Conference) in the first half of 1948 to discuss the future of Germany, going ahead despite Soviet threats to ignore any resulting decisions.[22][23] This resulted in the London Programme, aimed at creating economic revival and political re-structuring of the Western German zones.[12] In response to the announcement of the first of these meetings, in late January 1948, the Soviets began stopping British and American trains to Berlin to check passenger identities.[24] As outlined in an announcement on 7 March 1948, all of the governments present approved the extension of the Marshall Plan to Germany, finalised the economic merger of the western occupation zones in Germany and agreed upon the establishment of a federal system of government for them.[22][23]

After a 9 March meeting between Stalin and his military advisers, a secret memorandum was sent to Molotov on 12 March 1948, outlining a plan to force the policy of the western allies into line with the wishes of the Soviet government by "regulating" access to Berlin.[25] The Allied Control Council (ACC) met for the last time on 20 March 1948, when Vasily Sokolovsky demanded to know the outcome of the London Conference and, on being told by negotiators that they had not yet heard the final results from their governments, he said, "I see no sense in continuing this meeting, and I declare it adjourned."[25]

The entire Soviet delegation rose and walked out. Truman later noted,[26]

for most of Germany, this act merely formalised what had been an obvious fact for some time, namely, that the four-power control machinery had become unworkable. For the city of Berlin, however, this was an indication for a major crisis.

On 25 March 1948, the Soviets issued orders restricting Western military and passenger traffic between the American, British and French occupation zones and Berlin.[24] These new measures began on 1 April along with an announcement that no cargo could leave Berlin by rail without the permission of the Soviet commander. Each train and truck was to be searched by the Soviet authorities.[24] On 2 April, General Clay ordered a halt to all military trains and required that supplies to the military garrison be transported by air, in what was dubbed the "Little Lift."[24]

The Soviets eased their restrictions on Allied military trains on 10 April 1948, but continued periodically to interrupt rail and road traffic during the next 75 days, while the United States continued supplying its military forces by using cargo aircraft.[27] Some 20 flights a day continued through June, building up stocks of food against future Soviet actions,[28] so that by the time the blockade began at the end of June, at least 18 days' supply per major food type, and in some types, much more, had been stockpiled that provided time to build up the ensuing airlift.[29]

At the same time, Soviet military aircraft began to violate West Berlin airspace and would harass, or what the military called "buzz", flights in and out of West Berlin.[30] On 5 April, a Soviet Air Force Yakovlev Yak-3 fighter collided with a British European Airways Vickers Viking 1B airliner near RAF Gatow airfield, killing all aboard both aircraft. Later dubbed the Gatow air disaster, this event exacerbated tensions between the Soviets and the other allied powers.[31][32][33]

Internal Soviet reports in April stated that "Our control and restrictive measures have dealt a strong blow to the prestige of the Americans and British in Germany" and that the Americans have "admitted" that the idea of an airlift would be too expensive.[34]

On 9 April, Soviet officials demanded that American military personnel maintaining communication equipment in the Eastern zone must withdraw, thus preventing the use of navigation beacons to mark air routes.[27] On 20 April, the Soviets demanded that all barges obtain clearance before entering the Soviet zone.[35]

Deutsche Mark

Further information: Heinrich Rau, East German mark, and Deutsche Mark

The Deutsche Mark is introduced in the Western zones, and the USSR bans its use in the Eastern zone. On 22 June 1948, the Ostmark is introduced as currency in the Eastern zone. Creation of an economically stable western Germany required reform of the unstable Reichsmark German currency introduced after the 1920s German inflation. The Soviets continued the debasing of the Reichsmark, which had undergone severe inflation during the war, by excessive printing, resulting in many Germans using cigarettes as a de facto currency or for bartering. The Soviets opposed western plans for a reform. They interpreted the new currency as an unjustified, unilateral decision, and responded by cutting all land links between West Berlin and West Germany. The Soviets believed that the only currency that should be allowed to circulate was the currency that they issued themselves.

Anticipating the introduction of a new currency by the other countries in the non-Soviet zones, the Soviet Union in May 1948 directed its military to introduce its own new currency and to permit only the Soviet currency to be used in their sector of Berlin if the other countries brought in a different currency there. On 18 June the United States, Britain and France announced that on 21 June the Deutsche Mark would be introduced, but the Soviets refused to permit its use as legal tender in Berlin. The Allies had already transported 250,000,000 Deutsche marks into the city and it quickly became the standard currency in all four sectors.

The day after the 18 June 1948 announcement of the new Deutsche Mark, Soviet guards halted all passenger trains and traffic on the autobahn to Berlin, delayed Western and German freight shipments and required that all water transport secure special Soviet permission.[36] On 21 June, the day the Deutsche Mark was introduced, the Soviet military halted a United States military supply train to Berlin and sent it back to western Germany.[36] On 22 June, the Soviets announced that they would introduce the East German mark in their zone.[37]

Remove ads

The Berlin Blockade (June 1948 – May 1949)

Summarize

Perspective

Beginning of the blockade

Stalin wanted to stop Western currency getting into Berlin and some have argued that Stalin used the Berlin Blockade to prevent the creation of a Western German government.[38]

On 24 June 1948, Joseph Stalin ordered Soviet troops to block all rail and barge traffic in and out of Berlin.[39] The Soviets stated that the reason for withdrawing the West's access to Berlin was "technical difficulties" on the railways and roads.[13] Elecriticty was restricted to only 2 hours a day in the western areas of Berlin, something the Soviets explained as being the result of "severe shortages of electric current".[40] Since traffic from non-Soviet zones to Berlin were blockaded, only air corridors remained open. [citation needed] Believing that Britain, France, and the United States had little option other than to acquiesce, the Soviet Military Administration in Germany celebrated the beginning of the blockade.[41] General Clay felt that the Soviets were bluffing about Berlin since they would not want to be viewed as starting a Third World War. He believed that Stalin did not want a war and that Soviet actions were aimed at exerting military and political pressure on the West to obtain concessions, relying on the West's prudence and unwillingness to provoke a war.[42] General Curtis LeMay, commander of United States Air Forces in Europe (USAFE), reportedly favored an aggressive response to the blockade, in which his B-29s with fighter escort would approach Soviet air bases while ground troops attempted to reach Berlin; Washington vetoed the plan.[43] However, the West answered by introducing a counter-blockade, stopping all rail traffic into East Germany from the British and US zones. [citation needed] Over the following months, this counter-blockade would have a damaging impact on East Germany, as the drying up of coal and steel shipments seriously hindered industrial development in the Soviet zone.[44][45]

Western Response: The Berlin Airlift

Summarize

Perspective

Early on in the blockade, General Clay and other strategists including British Prime Minister Clement Attlee, were aware that a larger airlift may be required to support supplies to Berlin.[13]

Phase 1 (26 June – September 1948)

On 25 June 1948, Clay gave the order to launch Operation Vittles. The next day, 32 C-47s lifted off for Berlin hauling 80 tons of cargo, including milk, flour and medicine.[13] On 28 June 1948 LeMay appointed Brigadier General Joseph Smith, commander of the installation at Wiesbaden, as the Berlin Airlift Task Force Commander.[13] The airlift was named Operation Vittles by the Americans but,the British named it Operation Plane Fare. The first British aircraft flew on 28 June. At that time, the airlift was expected to last three weeks. [citation needed]

On 27 June, Clay cabled William Draper with an estimate of the current situation:

I have already arranged for our maximum airlift to start on Monday [June 28]. For a sustained effort, we can use seventy Dakotas [C-47s]. The number which the British can make available is not yet known, although General Robertson is somewhat doubtful of their ability to make this number available. Our two Berlin airports can handle in the neighborhood of fifty additional airplanes per day. These would have to be C-47s, C-54s or planes with similar landing characteristics, as our airports cannot take larger planes. LeMay is urging two C-54 groups. With this airlift, we should be able to bring in 600 or 700 tons a day. While 2,000 tons a day is required in normal foods, 600 tons a day (using dried foods to the maximum extent) will substantially increase the morale of the German people and will unquestionably seriously disturb the Soviet blockade. To accomplish this, it is urgent that we be given approximately 50 additional transport planes to arrive in Germany at the earliest practicable date, and each day's delay will of course decrease our ability to sustain our position in Berlin. Crews would be needed to permit maximum operation of these planes.

— Lucius D. Clay, June 1948[46]

By early July it was clear that the airlift would need to last longer than originally predicted, but a long-term airlift of this scale had never been attempted before.[13] In Washington, there was concern over the strategy and Assistant Security of the Air Force Cornelius V. Whitney told the National Security Council on 17 July 1948 that "the Air Staff was firmly convinced the air operation is dommed to failure." [47]

Military Air Transport Service (MATS)

Further information: Military Air Transport Service

MATS was established weeks prior to Operation Vittles, and they became involved on 30 June 1948. 35 MATS C-54's with crews arrived at Wiesbaden to aid the operation.[13] On 23 July 1948, MATS deputy commander Major General William H. Turner was made commander by Headquarters USAF to oversee the provisional Airlift Task Force Headquarters at Wiesbaden, including maintenance of facilities, air traffic control equipment and supporting personnel.[48] Tunner was focused on getting the most tonnage to Berlin a single day as safely and efficiently as possible. He envisioned operations at 3-minute intervals daily, and his precise approach earned him the nickname "Willie the Wip".[49][50]

The British ran a similar system, flying southeast from several airports in the Hamburg area through their second corridor into RAF Gatow in the British Sector, and then also returning out on the centre corridor, turning for home or landing at Hanover. However, unlike the Americans, the British also ran some round-trips, using their southeast corridor. To save time, many flights didn't land in Berlin, instead air dropping material, such as coal, into the airfields. On 6 July the Yorks and Dakotas were joined by Short Sunderland flying boats. Flying from Finkenwerder on the Elbe near Hamburg to the Havel river next to Gatow, their corrosion-resistant hulls suited them to the particular task of delivering baking powder and other salt into the city.[51] The Royal Australian Air Force also contributed to the British effort.

Accommodating the large number of flights to Berlin of dissimilar aircraft with widely varying flight characteristics required close co-ordination. Smith and his staff developed a complex timetable for flights called the "block system": three eight-hour shifts of a C-54 section to Berlin followed by a C-47 section. Aircraft were scheduled to take off every four minutes, flying 1,000 feet (300 m) higher than the flight in front. This pattern began at 5,000 feet (1,500 m) and was repeated five times. This system of stacked inbound serials was later dubbed "the ladder".[52][53][54]

During the first week, the airlift averaged only ninety tons a day, but by the second week it reached 1,000 tons. This likely would have sufficed had the effort lasted only a few weeks, as originally believed. The Communist press in East Berlin ridiculed the project. It derisively referred to "the futile attempts of the Americans to save face and to maintain their untenable position in Berlin."[55]

Despite the excitement engendered by glamorous publicity extolling the work (and over-work) of the crews and the daily increase of tonnage levels, the airlift was not close to being operated to its capability because USAFE was a tactical organisation without any airlift expertise. Maintenance was barely adequate, crews were not being efficiently used, transports stood idle and disused, necessary record-keeping was scant, and ad hoc flight crews of publicity-seeking desk personnel were disrupting a business-like atmosphere.[56] This was recognised by the United States National Security Council at a meeting with Clay on 22 July 1948, when it became clear that a long-term airlift was necessary. Wedemeyer immediately recommended that the deputy commander for operations of the Military Air Transport Service (MATS), Maj. Gen. William H. Tunner, command the operation. When Wedemeyer had been the commander of US forces in China during World War II, Tunner, as commander of the India-China Division of the Air Transport Command, had reorganised the Hump airlift between India and China, doubling the tonnage and hours flown. USAF Chief of Staff Hoyt S. Vandenberg endorsed the recommendation.[52]

Black Friday

On 28 July 1948, Tunner arrived in Wiesbaden to take over the operation.[57] He reached an agreement with LeMay to form the Combined Airlift Task Force (CALTF), overseen by the United States Air Forces Europe (USAFE), which had responsibility over the coalition effort to support supplies to Berlin. On 30 July 1948, the Airlift Task Force (Provisional) was formed, however, there was coordination issues between the British and American operations due to increasing air traffic.[58] Following discussions, the CALTF was officially established on 15 October 1948 and controlled both the USAFE and RAF lift operations from a central location. General Clay directed the Army to be in charge of transporting supplies to the airfields, whereas the commander of the Airlift Task Force had operational control over air communications service.[58]

On 2 July 1948, approximately 100 C-47s from the European Air Transport Service were delivering supplies to Berlin, and by 20 July the USAF had increased its contribution to 105 C-47s and 54 C-54s.[58] The British added to this with 40 Yorks and 50 C-47s, making the total daily effort 2,250 tons.[59]

MATS deployed eight squadrons of C-54s—72 aircraft—to Wiesbaden and Rhein-Main Air Base to reinforce the 54 already in operation, the first by 30 July and the remainder by mid-August, and two-thirds of all C-54 aircrew worldwide began transferring to Germany to allot three crews per aircraft.[60]

Two weeks after his arrival, on 13 August, Tunner decided to fly to Berlin to grant an award to Lt. Paul O. Lykins, an airlift pilot who had made the most flights into Berlin up to that time, a symbol of the entire effort to date.[61] Cloud cover over Berlin dropped to the height of the buildings, and heavy rain showers made radar visibility poor. A C-54 crashed and burned at the end of the runway, and a second one landing behind it burst its tires while trying to avoid it. A third transport ground looped after mistakenly landing on a runway under construction. In accordance with the standard procedures then in effect, all incoming transports including Tunner's, arriving every three minutes, were stacked above Berlin by air traffic control from 3,000 to 12,000 feet (910 to 3,660 m) in bad weather, creating an extreme risk of mid-air collision. Newly unloaded planes were denied permission to take off to avoid that possibility and created a backup on the ground. While no one was killed, Tunner was embarrassed that the control tower at Tempelhof had lost control of the situation while the commander of the airlift was circling overhead. Tunner radioed for all stacked aircraft except his to be sent home immediately. This became known as "Black Friday", and Tunner personally noted it was from that date onward that the success of the airlift stemmed.[62][63]

As a result of Black Friday, Tunner instituted a number of new rules; instrument flight rules (IFR) would be in effect at all times, regardless of actual visibility, and each sortie would have only one chance to land in Berlin, returning to its air base if it missed its approach, where it was slotted back into the flow. Stacking was eliminated. With straight-in approaches, the planners found that in the time it had taken to unstack and land nine aircraft, 30 aircraft could be landed, bringing in 300 tons.[64] Accident rates and delays dropped immediately. Tunner decided, as he had done during the Hump operation, to replace the C-47s in the airlift with C-54s or larger aircraft when it was realised that it took just as long to unload a 3.5-ton C-47 as a 10-ton C-54. One of the reasons for this was the sloping cargo floor of the "taildragger" C-47s, which made truck loading difficult. The tricycle geared C-54's cargo deck was level, so that a truck could back up to it and offload cargo quickly. The change went into full effect after 28 September 1948.[65]

Having noticed on his first inspection trip to Berlin on 31 July that there were long delays as the flight crews returned to their aircraft after getting refreshments from the terminal, Tunner banned aircrew from leaving their aircraft for any reason while in Berlin. Instead, he equipped jeeps as mobile snack bars, handing out refreshments to the crews at their aircraft while it was being unloaded. Airlift pilot Gail Halvorsen later noted, "he put some beautiful German Fräuleins in that snack bar. They knew we couldn't date them, we had no time. So they were very friendly."[66] Operations officers handed pilots their clearance slips and other information while they ate. With unloading beginning as soon as engines were shut down on the ramp, turnaround before takeoff back to Rhein-Main or Wiesbaden was reduced to thirty minutes.[67]

To maximise the use of a limited number of aircraft, Tunner altered the "ladder" to three minutes and 500 feet (150 m) of separation, stacked from 4,000 to 6,000 feet (1,200 to 1,800 m).[53] Maintenance, particularly adherence to 25-hour, 200-hour, and 1,000-hour inspections, became the highest priority and further maximised use.[68] Tunner also shortened block times to six hours to squeeze in another shift, making 1,440 (the number of minutes in a day) landings in Berlin a daily goal.[69] His purpose, illustrating his basic philosophy of the airlift business, was to create a "conveyor belt" approach to scheduling that could be sped up or slowed down as situations might dictate. The most effective measure taken by Tunner, and the most initially resisted until it demonstrated its efficiency, was creation of a single control point in the CALTF for controlling all air movements into Berlin, rather than each air force doing its own.

The Berliners themselves solved the problem of the lack of manpower. Crews unloading and making airfield repairs at the Berlin airports were made up almost entirely of local civilians, who were given additional rations in return. As the crews increased in experience, the times for unloading continued to fall, with a record set for the unloading of an entire 10-ton shipment of coal from a C-54 in ten minutes, later beaten when a twelve-man crew unloaded the same quantity in five minutes and 45 seconds.

By August 1948, Rhein-Main and Wiesbaden were the two German airfields facilitating American flights to Berlin. Tunner wanted to expand American operation bases to be closer to Berlin, and on 4 August 1948 preliminary plans were put in place for expansion to RAF Fassberg, in the British sector.[13] Tunner's airlift also began to expand operations within Berlin, and on 20 August active flights into Gatow began, in addition to the existing use of Tempelhof.[13]

By the end of August 1948, after two months, the airlift was succeeding; daily operations flew more than 1,500 flights a day and delivered more than 4,500 tons of cargo, enough to keep West Berlin supplied.

Phase 2 (October 1948 – March 1949)

On 20 October, the Office of Military Government increased the daily supply requirement Berlin from 4,500 to 5,620 tons: 1,435 tons for food, 3,084 tons for coal, 255 tons for commerce and industry supplies, 35 tons for newsprint, 16 tons for liquid fuel, 2 tons for medical supplies, 763 for the US, British and French Military, and 30 tons for C54 passenger flights (US and French).[70]

Preparing for winter

Although the early estimates were that about 4,000 to 5,000 tons per day would be needed to supply the city, this was made in the context of summer weather, when the airlift was only expected to last a few weeks. As the operation dragged on into autumn, the situation changed considerably. The food requirements would remain the same (around 1,500 tons), but the need for additional coal to heat the city dramatically increased the total amount of cargo to be transported by an additional 6,000 tons a day.

To maintain the airlift under these conditions, the current system would have to be greatly expanded. Aircraft were available, and the British started adding their larger Handley Page Hastings in November, but maintaining the fleet proved to be a serious problem. Tunner looked to the Germans once again, hiring former Luftwaffe mechanics.

Another problem was the lack of runways in Berlin to land on: two at Tempelhof and one at Gatow—neither of which was designed to support the loads the C-54s were putting on them. All of the existing runways required hundreds of labourers, who ran onto them between landings and dumped sand into the runway's Marston Mat (pierced steel planking) to soften the surface and help the planking survive. Since this system could not endure through the winter, between July and September 1948 a 1,800-metre (5,900 ft)-long asphalt runway was constructed at Tempelhof.

Far from ideal, with the approach being over Berlin's apartment blocks, the runway nevertheless was a major upgrade to the airport's capabilities. With it in place, the auxiliary runway was upgraded from Marston Matting to asphalt between September and October 1948. A similar upgrade program was carried out by the British at Gatow during the same period, also adding a second runway, using concrete.

The French Air Force, meanwhile, had become involved in the First Indochina War, so it could only bring up a few French built Junkers Ju 52s (known as A.A.C. 1 Toucan) to support its own troops, and they were too small and slow to be of much help. However, France agreed to build a complete, new and larger airport in its sector on the shores of Lake Tegel. French military engineers, managing German construction crews, were able to complete the construction in under 90 days. Because of a shortage of heavy equipment, the first runway was mostly built by hand, by thousands of labourers who worked day and night.[71]

For the second runway at Tegel, heavy equipment was needed to level the ground, equipment that was too large and heavy to fly in on any existing cargo aircraft. The solution was to dismantle large machines and then re-assemble them. Using the five largest American C-82 Packet transports, it was possible to fly the machinery into West Berlin. This not only helped to build the airfield, but also demonstrated that the Soviet blockade could not keep anything out of Berlin. The Tegel airfield was subsequently developed into Berlin Tegel Airport.

The winter of 1948-1949 was one of the worst on record and resulted in fog, low ceilings and low visibility, and the Allies used technology as mitigation. The Allied forecasters gathered historical weather date from the last 40 years, and weather stations were in the United States, the Arctic, and at sea provided long-forecast information.[58] A radio operator was stationed in every seventh aircraft in order to report current weather conditions at critical points in the flight path.[72] A weather officer was also appointed to Tunner's staff, and the officer had daily phone calls with other weather personnel to produce a comprehensive forecast for airlift managers.[13] Tunner complained to the MATS commander on 21 August 1948, writing that they were lacking air traffic controllers in the Air Force.[73] The number of air traffic controllers increased as supplied by the Army Airways and Air Communications Service (AACS), and at the peak of the operation there were 90 AACS officers assisting the airlift.[74]

Peak and Easter Offensive (April 1949)

The U.S. Air Force reported delivering 2,325,609.6 tons of supplies to Berlin.[39] 76 percent of this total were supplied by the U.S. Air Force, 17 percent by the Royal Air Force, and 7 percent by British civilian planes.[75]

In January 1949, Major General Laurence S. Kuter, commander of the Military Air Transport Service, praised the pilots actions in a speech at the Institute of Aeronautical Sciences saying "For the first time in peacetime history, strategic air transport has become a conspicuous expression of American air power, peace power, and an effective weapon of diplomacy." [76]

By April 1949, airlift operations were running smoothly and Tunner wanted to shake up his command to discourage complacency. He believed in the spirit of competition between units and, coupled with the idea of a big event, felt that this would encourage them to greater efforts. He decided that, on Easter Sunday, the airlift would break all records. To do this, maximum efficiency was needed and so, to simplify cargo-handling, only coal would be airlifted. Coal stockpiles were built up for the effort and maintenance schedules were altered so that the maximum number of aircraft were available.[77]

From noon on 15 April to noon on 16 April 1949, crews worked around the clock. When it was over, 12,941 tons of coal had been delivered in 1,383 flights, without a single accident.[77] A welcome side effect of the effort was that operations in general were boosted, and tonnage increased from 6,729 tons to 8,893 tons per day thereafter. In total, the airlift delivered 234,476 tons in April.[55]

On 21 April, the tonnage of supplies flown into the city exceeded that previously brought by rail. [citation needed]

The Soviet resolve was beginning to decline by early 1949. On 25 April, it was announced by TASS news agency that the Soviet Union was open to ending the blockade.

Civilian experience and humanitarian efforts

When the blockade began, some German people in the Soviet zones could get food in packages through the post, if they had connections to people in West Germany.[78] During the blockade, Western sectors from East Berlin or the countryside were never sealed off, and as a result, nearly half a million tons of goods came into the Western sectors from Soviet zone sources.[78] There was, thus, a black market operation, and a number of West Berliners went to the countryside to forage, bartering or using the Westmark to secure goods.[78] By November 1948, so-called Free Shops began in East Berlin and Brandenburg allowing West Berliners to purchase provisions using the Eastmark. Some West Berlin companies cooperated with individual Soviet zone companies and the Deutsche Wirtscheftskommission (DWK) to produce goods for Soviet and East German people at a cost of raw materials and money.[78]

April "Little Lift"

Further Information: Raisin Bombers

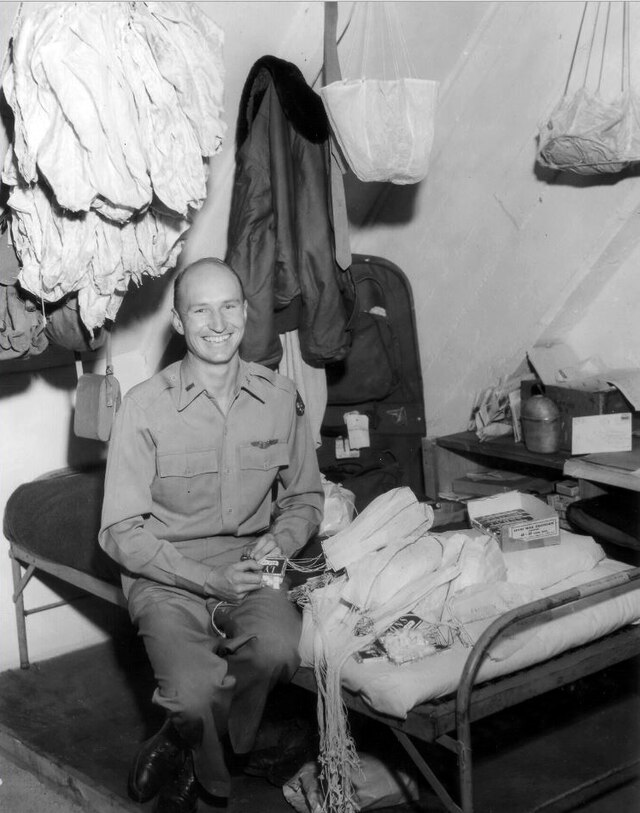

An important operation for maintaining the morale of Berliners was "Operation Little Vittles". Lieutenant Gail Halvorsen, one of the many airlift pilots, decided to use his off-time to fly into Berlin and make movies with his hand-held camera. [citation needed] He arrived at Tempelhof on 17 July 1948 on one of the C-54s and walked over to a crowd of children who had gathered at the end of the runway to watch the aircraft. As a goodwill gesture, he handed out his only two sticks of Wrigley's Doublemint Gum. The children quickly divided up the pieces as best they could, even passing around the wrapper for others to smell. He was so impressed by their gratitude and that they didn't fight over them, that he promised the next time he returned he would drop off more. Before he left them, a child asked him how they would know it was him flying over. He replied, "I'll wiggle my wings."[79]

The next day on his approach to Berlin, he rocked the aircraft and dropped some chocolate bars attached to a parachute made from a handkerchief to the children waiting below. Every day after that, the number of children increased and he made several more drops. Soon, there was a stack of mail in Base Ops addressed to "Uncle Wiggly Wings", "The Chocolate Uncle" and "The Chocolate Flier". His commanding officer was upset when the story appeared in the news, but when Tunner heard about it, he approved of the gesture and immediately expanded it into "Operation Little Vittles". Other pilots participated, and when news reached the US, children all over the country sent in their own candy to help out. Soon, major candy manufacturers joined in. In the end, over three tons of candy were dropped on Berlin and the "operation" became a major propaganda success. German children christened the candy-dropping aircraft "raisin bombers" or candy bombers.

Remove ads

End of the Blockade (May–September 1949)

Summarize

Perspective

On 25 April 1949, the Soviet news agency TASS reported a willingness by the Soviets to lift the blockade. The next day, the US State Department stated that the "way appears clear" for the blockade to end.[citation needed] Soon afterwards, the four powers began serious negotiations, and a settlement was reached on Western terms. On 4 May 1949, the Allies announced an agreement to end the blockade in eight days.

The Soviet blockade of Berlin was lifted at one minute after midnight on 12 May 1949. A British convoy immediately drove through to Berlin, and the first train from West Germany reached Berlin at 5:32 am. Later that day, an enormous crowd celebrated the end of the blockade. General Clay, whose retirement had been announced by US President Truman on 3 May 1949, was saluted by 11,000 US soldiers and dozens of aircraft. Once home, Clay received a ticker tape parade in New York City, was invited to address the US Congress, and was honoured with a medal from President Truman.

Nevertheless, supply flights to Berlin continued for some time to build up a comfortable surplus, though night flying and then weekend flights could be eliminated once the surplus was deemed to be large enough. By 24 July 1949, three months' worth of supplies had been amassed, ensuring that there was ample time to restart the airlift if needed.

On 18 August 1949, Flt Lt Roy Mather DFC AFC and his crew of Flt Lt Roy Lewis Stewart Hathaway AFC, Flt Lt Richardson and Royston William Marshall AFM of 206 squadron, flew back to Wunstorf for the 404th time during the blockade, the record number of flights for any pilot of any nationality, either civilian or military.

The Berlin Airlift officially ended on 30 September 1949, after fifteen months.

Remove ads

Soviet response and international diplomacy

Summarize

Perspective

Soviet propaganda and negotiations

As of June 1948, the Soviets launched a campaign against Yugoslavia and Joseph Broz Tito saying they are "agents of the Anglo-Americans".[19] The Soviets said that they would lift the blockade when West Germany agreed to put aside their plans to introduce the Western B mark in Berlin.[80] Stalin believed that the West would capitulate when they realised how difficult it would be to supply Berlin with adequate resources to make it through the winter.[80] He was confident that the West could not afford to go to war over the issue, but the West were just as convinced that Stalin would not go to war. The Soviets also believed that West Berliners, suffering under the increasing shortages, would pressure the allies in conceding and intensify this the Soviets excluded West Berliners from the Berlin Magistrat and took command of the city's police force.[80] Soviet communist propaganda was prevalent, throughout the time of the blockade, on the radio, in the press, pamphlets and posters, and streetcorner meetups.[81] However, the municipal elections in December 1948, showed that almost 85 percent of West Berliners voted against communist parties. In the summer and autumn of 1948, Soviet propaganda began to rally against "cosmopolitans" and categorising them as an American "fifth column" and the press highlighted stories uncovering cosmopolitans within Soviet culture.[19]

Shift in public opinion

Public opinion shifted during the blockade and there was a sharp decline in interest in communism. For example, an opinion poll in August 1948 showed that 80 percent of those polled listened most to RIAS (a US sponsored radio station in Berlin), whereas only 15 percent listened more to Radio Berlin (a Soviet-run station).[82] The Blockade shifted public postwar apathy, and it gave people a sense of political purpose. On 9 September 1949, a rally of nearly 300,000 Berliners gathered at the Brandenberg Gate to protest against the violence of the East German authorities. Ernst Reuter highlighted this rally saying this showed the strength of Berliners to protect their liberty.[83] The blockade ultimately failed because of the airlift operation, but also because of the resolve of West Berliners. They subsisted on rations, cold homes, only four hours of electricity a day, whilst also being promised food, fuel and employment if they resisted and followed Soviet instructions.[81] Western news outlets also published articles to communicate the issues facing Berlin during the crisis. Two stories from Time and Life wrote about the blockade calling it "The Siege", and a March of Time article discussed the wider concerns about Germany and its future.[84] General Clay was featured on the cover of Time on July 8, 1948. [citation needed]

Remove ads

Aftermath

Summarize

Perspective

The Soviets had an advantage in conventional military forces, but were preoccupied with rebuilding their war-torn economy and society. The US had a stronger navy and air force, and had nuclear weapons. Neither side wanted a war; the Soviets did not disrupt the airlift.[85]

Aftermath for Berlin

As the tempo of the airlift grew, it became apparent that the Western powers might be able to pull off the impossible: indefinitely supplying an entire city by air alone. In response, starting on 1 August 1948, the Soviets offered free food to anyone who crossed into East Berlin and registered their ration cards there, and almost 22 thousand Berliners received their cards until 4 August 1948.[86] The great majority of West Berliners, however, rejected Soviet offers of food and supplies.[87]

Throughout the airlift, Soviet and German communists subjected the hard-pressed West Berliners to sustained psychological warfare.[87] In radio broadcasts, they relentlessly proclaimed that all Berlin came under Soviet authority and predicted the imminent abandonment of the city by the Western occupying powers.[87] The Soviets also harassed members of the democratically elected citywide administration, which had to conduct its business in the city hall located in the Soviet sector.[87]

According to the "Berlin Airlift Corridor Incidents Report", which spanned the period between 10 August 1948 and 5 August 1949, there were 733 incidents reported between Soviet and Allied airlift aircraft.[58] During the early months of the airlift, the Soviets used various methods to harass allied aircraft. These included buzzing by Soviet planes, obstructive parachute jumps within the corridors, and shining searchlights to dazzle pilots at night. None of these measures were effective.[88][89] Former RAF Dakota pilot Dick Arscott described one "buzzing" incident. "Yaks (Soviet fighter aircraft) used to come and buzz you and go over the top of you at about twenty feet which can be off-putting. One day I was buzzed about three times. The following day it started again and he came across twice and I got a bit fed up with it. So when he came for the third time, I turned the aircraft into him and it was a case of chicken, luckily he was the one who chickened out."[90] General Tunner said "They were seen by pilots and were sometimes close, but they were never more than a moral threat." [70]

Attempted Communist putsch in the municipal government

In the autumn of 1948 it became impossible for the non-Communist majority in Greater Berlin's citywide parliament to attend sessions at city hall within the Soviet sector.[87] The parliament (Stadtverordnetenversammlung von Groß-Berlin) had been elected under the provisional constitution of Berlin two years earlier (20 October 1946). As SED-controlled policemen looked on passively, Communist-led mobs repeatedly invaded the Neues Stadthaus, the provisional city hall (located on Parochialstraße since all other central municipal buildings had been destroyed in the War), interrupted the parliament's sessions, and menaced its non-Communist members.[87] The Kremlin organised an attempted putsch for control of all of Berlin through a 6 September takeover of the city hall by SED members.[91]

Three days later RIAS Radio urged Berliners to protest against the actions of the communists. On 9 September 1948 a crowd of 500,000 people gathered at the Brandenburg Gate, next to the ruined Reichstag in the British sector. The airlift was working so far, but many West Berliners feared that the Allies would eventually discontinue it. Then-SPD city councillor Ernst Reuter took the microphone and pleaded for his city, "You peoples of the world, you people of America, of England, of France, look on this city, and recognise that this city, this people, must not be abandoned—cannot be abandoned!"[66]

The crowd surged towards the Soviet-occupied sector and someone climbed up and ripped down the Soviet flag flying from atop the Brandenburg Gate. Soviet military police (MPs) quickly responded, resulting in the killing of one in the unruly crowd.[66] The tense situation could have escalated further and ended up in more bloodshed, but a British deputy provost then intervened and pointedly pushed the Soviet MPs back with his swagger stick.[92] Never before this incident had so many Berliners gathered in unity. The resonance worldwide was enormous, notably in the United States, where a strong feeling of solidarity with Berliners reinforced a general widespread determination not to abandon them.[91]

Berlin's parliament decided to meet instead in the canteen of the Technische Hochschule in Berlin (now Technische Universität Berlin) in the British sector, boycotted by the members of SED, which had gained 19.8% of the electoral votes in 1946. On 30 November 1948 the SED gathered its elected parliament members and 1,100 further activists and held an unconstitutional so-called "extraordinary city assembly" (außerordentliche Stadtverordnetenversammlung) in East Berlin's Metropol-Theater which declared the elected city government (Magistrat) and its democratically elected city councillors to be deposed and replaced it with a new one led by Oberbürgermeister Friedrich Ebert Jr. and consisting only of Communists.[91] This arbitrary act had no legal effect in West Berlin, but the Soviet occupants prevented the elected city government for all of Berlin from further acting in the eastern sector.

December elections

The city parliament, boycotted by its SED members, then voted for its re-election on 5 December 1948, however, inhibited in the eastern sector and denounced by the SED as a Spalterwahl ("divisive election"). The SED did not nominate any candidates for this election and appealed to the electorate in the western sectors to boycott the election, while the democratic parties ran for seats. The turnout amounted to 86.3% of the western electorate with the SPD gaining 64.5% of the votes (= 76 seats), the CDU 19.4% (= 26 seats), and the Liberal-Demokratische Partei (LDP, merged in the FDP in 1949) 16.1% (= 17 seats).[87]

On 7 December the new, de facto West-Berlin-only city parliament elected a new city government in West Berlin headed by Lord Mayor Ernst Reuter, who had already once been elected lord mayor in early 1946 but prevented from taking office by a Soviet veto.[91] Thus two separate city governments officiated in the city divided into East and West versions of its former self. In the east, a communist system supervised by house, street, and block wardens was quickly implemented.

West Berlin's parliament accounted for the de facto political partition of Berlin and replaced the provisional constitution with the new Constitution of Berlin, meant for all Berlin, with effect of 1 October 1950 and de facto restricted to the western sectors only, also renaming city parliament from Stadtverordnetenversammlung von Groß-Berlin (City Council of Greater Berlin) to Abgeordnetenhaus von Berlin (House of Representatives of Berlin), city government (from Magistrat von Groß-Berlin (City Council of Greater Berlin) to Senate of Berlin, and head of government (from Oberbürgermeister (Mayor) to Governing Mayor of Berlin.[93]

Remove ads

Consequences

Summarize

Perspective

Casualities, costs and logistics

In total, the USAF delivered 1,783,573 tons and the RAF 541,937 tons, totalling 2,326,406 tons, nearly two-thirds of which was coal, on 278,228 flights to Berlin.[7] The C-47s and C-54s together flew over 92,000,000 miles (148,000,000 km) in the process, almost the distance from Earth to the Sun.[7] At the height of the airlift, one plane reached West Berlin every thirty seconds.[8]

Pilots came from the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and South Africa.[94][95] The Royal Australian Air Force delivered 7,968 tons of freight and 6,964 passengers during 2,062 sorties.

A total of 101 fatalities were recorded as a result of the operation, including 40 Britons and 31 Americans,[8] mostly due to non-flying accidents.[9] One Royal Australian Air Force member was killed in an aircraft crash at Lübeck while attached to No. 27 Squadron RAF.[96] Seventeen American and eight British aircraft crashed during the operation.

The cost of the airlift was shared between the US, UK, and German authorities in the Western sectors of occupation. Estimated costs range from approximately US$224 million[97] to over US$500 million (equivalent to approximately $2.33 billion to $5.21 billion in 2024).[98][94][99]

Operational control of the three Allied air corridors was assigned to BARTCC (Berlin Air Route Traffic Control Center) air traffic control located at Tempelhof. Diplomatic approval was granted by a four-power organisation called the Berlin Air Safety Centre, also located in the American sector.

The experience led Washington to consider Stalin's next moves, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff calculated that, if not imminently, the Soviet Union could invoke military action. As a result, Washington began preemtivaley planning a war that could come by 1957, and anticipated the use of atomic weapons.[100]

Senate reserve

Following the end of the blockade, the Western Allied Powers required the Senate of Berlin to stockpile six months worth of food and basic necessities as preparation against a potential second Berlin blockade. The reserves were liquidated following reunification.

Berlin crises 1946–1962

Millions of East Germans escaped to West Germany from East Germany, and Berlin became a major escape route. This led to major-power conflict over Berlin that stretched at least from 1946 to the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961.[101] Dwight D. Eisenhower became US president in 1953 and Nikita Khrushchev became Soviet leader in the same year. Khrushchev tried to push Eisenhower on Berlin in 1958–59. The Soviets backed down when Eisenhower's resolve seemed to match that of Truman. When Eisenhower was replaced by Kennedy in 1961, Khrushchev tried again, with essentially the same result.[102]

Other developments

In the late 1950s, the runways at West Berlin's city centre Tempelhof Airport had become too short to accommodate the new-generation jet aircraft,[103] and Tegel was developed into West Berlin's principal airport. During the 1970s and 1980s Schönefeld Airport had its own crossing points through the Berlin Wall and communist fortifications for western citizens.

The Soviets' contravention by the blockade of the agreement reached by the London 6-Power Conference, and the Czechoslovak coup d'état of 1948, convinced Western leaders that they had to take swift and decisive measures to strengthen the portions of Germany not occupied by the Soviets.[8]

The US, British and French authorities also agreed to replace their military administrations in their occupation zones with High Commissioners operating within the terms of a three-power occupation statute.[104] The Blockade also helped to unify German politicians in these zones in support of the creation of a West German state; some of them had hitherto been fearful of Soviet opposition.[104] The blockade also increased the perception among many Europeans that the Soviets posed a danger, helping to prompt the entry into NATO of Portugal, Iceland, Italy, Denmark, and Norway.[105]

It has been claimed that animosities between Germans and the Western Allies were greatly reduced by the airlift, with the former enemies recognising common interests.[106][107] The Soviets refused to return to the Allied Control Council in Berlin, rendering the four-power occupation authority set up at the Potsdam Conference useless.[example needed][8] It has been argued that the events of the Berlin Blockade are proof that the Allies conducted their affairs within a rational framework, since they were keen to avoid war.[108]

Remove ads

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

Debate and analysis

The blockade marked a crucial point in the Cold War, and Stalin took a calculated military risk; one which has been argued to alter the East and West relationship.[109] The Berlin Airlift helped to secure the freedom of Berlin and demonstrated Allied strength and unity to the Soviet Union.[58] Reflecting on the blockade and airlift in, President Truman said:[110]

There was only oneway to avoid a third world war, and that was to lead from strength. We had to rearm ourselves and our allies and, at the same time, deal with the Russians in a manner they could never interpret as weakness.

— President Truman, Years of Trial and Hope (1956)

Post-Cold War

In 2007, Tegel was joined by a re-developed Berlin-Schönefeld International Airport in Brandenburg. As a result of the development of these two airports, Tempelhof was closed in October 2008,[111] while Gatow became home of the Bundeswehr Museum of Military History – Berlin-Gatow Airfield and a housing development. In October 2020, the expansion of Schönefeld into the larger Berlin Brandenburg Airport was completed, making Tegel mostly redundant as well.

Aircraft used in the Berlin Airlift

Summarize

Perspective

United States

- Boeing C-97 Stratofreighter

- Consolidated B-24 Liberator

- Consolidated PBY Catalina

- Douglas C-54 Skymaster and Douglas DC-4

- Douglas C-74 Globemaster

- Douglas C-47 Skytrain and Douglas DC-3

- Fairchild C-82 Packet

- Lockheed C-121A Constellation

- Douglas C-47 Skytrain

- Douglas C-74 Globemasters

- A Douglas C-54 Skymaster, called Spirit of Freedom, operated as a flying museum. It is owned and operated by the Berlin Airlift Historical Foundation.

- Boeing Stratofreighter

- Fairchild XC-82 Packet

- Lockheed C-69 Constellation

In the early days, the Americans used their C-47 Skytrain or its civilian counterpart Douglas DC-3. These machines could carry a payload of up to 3.5 tons, but were replaced by C-54 Skymasters and Douglas DC-4s, which could carry up to 10 tons and were faster. These made up a total of 330 aircraft, which made them the most used types. Other American aircraft such as the five C-82 Packets, and the one YC-97A Stratofreighter 45-59595, with a payload of 20 tons—a gigantic load for that time—were only sparsely used.

British

- Avro Lancaster

- Avro Lincoln

- Avro York

- Avro Tudor

- Avro Lancastrian

- Bristol Type 170 Freighter

- Douglas DC-3 (Dakota)

- Handley Page Hastings

- Handley Page Halifax Halton

- Short Sunderland

- Vickers VC.1 Viking

- Bristol Freighter

- Short Sunderland flying boat

- Avro Tudor

- Handley Page Hastings on display at the Alliiertenmuseum (Allied Museum), Berlin, Germany

The British used a considerable variety of aircraft types. Many aircraft were either former bombers or civil versions of bombers. In the absence of enough transports, the British chartered many civilian aircraft. British European Airways (BEA) coordinated all British civil aircraft operations. Apart from BEA itself, the participating airlines included British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) and most British independent[nb 2] airlines of that era—e.g. Eagle Aviation,[112] Silver City Airways, British South American Airways (BSAA), the Lancashire Aircraft Corporation, Airwork, Air Flight, Aquila Airways, Flight Refuelling Ltd (which used their Lancaster tankers to deliver aviation fuel), Skyways, Scottish Airlines and Ciro's Aviation.

Altogether, BEA was responsible to the RAF for the direction and operation of 25 British airlines taking part in "Operation Plainfare".[113] The British also used flying boats, particularly for transporting corrosive salt. These included civilian aircraft operated by Aquila Airways.[114] These took off and landed on water and were designed to be corrosion-resistant. Additionally, their roof-mounted control cables were protected against corrosion. In winter, when ice covered the Berlin rivers and made the use of flying boats difficult, the British used other aircraft in their place.

Altogether, a total of 692 aircraft were engaged in the Berlin Airlift, more than 100 of which belonged to civilian operators.[115]

Other aircraft included Junkers Ju 52/3m which were operated briefly by France.

Remove ads

See also

- Armageddon: A Novel of Berlin, 1963 novel by Leon Uris chronicling the airlift

- Berlin Airlift Device for the Army of Occupation and Navy Occupation Service Medals

- The Big Lift, a 1950 film about the experiences of some Americans during the airlift

- Deutsche Mark § Currency reform of June 1948

- East German mark § Currency reform

- Medal for Humane Action, American medal for the airlift

- Heinrich Rau § 1945–1949, chairman of the East German administration at the time

- Wolfgang Scheunemann, 15-year-old killed by the Volkspolizei during the blockade

- 1949 East German State Railway strike

- Berlin Crisis of 1958–1959

- Berlin Crisis of 1961

Remove ads

Footnotes

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads