Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Bobby Fischer Teaches Chess

1966 book by Bobby Fischer From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Bobby Fischer Teaches Chess is a chess puzzle book written by Bobby Fischer and co-authored by Stuart Margulies and Donn Mosenfelder, originally published in 1966. It is one of the best-selling chess books of all time with over one million copies sold.[1]

Remove ads

Overview

Summarize

Perspective

Problem No. 22

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

White to move and mate

The book is intended for beginners and uses a programmed learning approach,[2] permitting readers to go back and retry each question if they give a wrong answer. Unusually for a modern chess book, it requires no knowledge of chess notation, using only diagrams with arrows and descriptions such as "rook-takes-pawn-check".[3] The puzzles focus largely on finding checkmate; combinations involving back rank mates are particularly emphasized.

The book begins with an explanation of the rules of chess, followed by six chapters:

- Introduction: How to Play Chess

- Elements of Checkmate

- The Back-Rank Mates

- Back-Rank Defenses and Variations

- Displacing Defenders

- Attacks on the Enemy Pawn Cover

- Final Review

The text includes 19 examples adapted from Fischer's real games played between 1957 and 1965.[4][5][6] The examples are variously presented as chapter-ending lessons, problems involving board positions which actually occurred in the cited games, or otherwise as close variations which could have occurred (but didn't) in the real games, to illustrate simple themes. Problem No. 22 was adapted from Fischer–Larsen, Yugoslavia 1958, with White to move and mate.[7] The real game's closest and penultimate position was 30...Rd8, a matching position except for White's queen at d2 and Black's bishop at f6; the variation [31.Qh6+ Bg7] is an example of arriving at the book's position.[8]

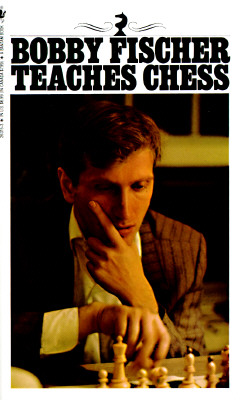

The cover of the book shows Fischer using his favorite Dubrovnik chess set.[9]

Remove ads

Publishing history

The book was originally published in 1966 by Basic Systems Inc,[10] a subsidiary of Xerox.[11][12] A paperback edition was published by Bantam Books in 1967 and sold 10,000 copies by early 1972. Due to the interest in the 1972 Fischer–Spassky World Championship match, the book was reprinted eight times that year alone.[13]

In 1994, Interplay Entertainment released a computer chess program of the same name based on the book.[14] The software received mixed reviews, PC Gamer noting the "ugly 2-D board" and Entertainment Weekly describing the lessons as "humorless... dogmatic, and fearsome".[15]

Remove ads

Authorship

The extent of Fischer's involvement in the book has been questioned. Andrew Soltis writes that Fischer "contributed some ideas, but chiefly his name".[16] Brady says that Fischer concentrated on working on it after the Capablanca Memorial chess tournament in 1965 and that Mosenfelder, Margulies, and Leslie Ault, who were all strong players, as well as educational experts, "helped him in outlining and editing the work".[17] According to Margulies, Fischer wanted a high-quality work free of any errors, so Michael Valvo and Raymond Weinstein were brought in as proofreaders.[13]

Reception

Chiefly due to its accessibility for beginners and Fischer's high public profile, the book sold an estimated one million copies. It is difficult to determine chess book sales with certainty, but this figure, based on the royalty payments made to co-author Stuart Margulies, makes it a candidate for best-selling chess book of all time.[1] In October 1972, following Fischer's victory in the World Championship, the Bantam edition appeared on The New York Times best-seller list at No. 2 on the general paperback list. It remained in this position for four weeks.[18]

Frank Brady, who was hired by Basic Systems as a promotional consultant, later said the book "lacked color or even a fleeting glimpse into the real way Bobby's mental processes work" and that it "was not ... one of the great introductory chess treatises of modern times".[17] The Times Literary Supplement, reviewing a 1973 British edition, criticized Fischer's grammar as well as the lack of content, which they said could have been compressed to fifty pages.[19]

Remove ads

Popular culture

- The book is referenced in Janet Fitch's novel White Oleander.[20]

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads