Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Byzantine literature of the Heraclian dynasty

Byzantine literature from 610 to 717 under the Heraclian dynasty From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Byzantine literature of the Heraclian dynasty spans the period of Byzantine literature from the ascension of Emperor Heraclius in 610 to the rise of the Isaurian dynasty in 717.

The reign of Heraclius (610–641) fostered the work of several notable authors. The historian Theophylact Simocatta wrote History of the World, covering Byzantine events from 582 to 602, and the widely read Letters on Moral, Pastoral, and Amorous Themes. George of Pisidia chronicled Heraclius' campaigns against the Persians in numerous historical poems, alongside philosophical-dogmatic works and epigrams. The preeminent theologian of the period, Maximus the Confessor, combated Monophysitism and Monothelitism in works such as To Maris, On the Soul, and Letters, while also producing exegetical, liturgical, and ascetic writings. Another distinguished theologian, Sophronius, Patriarch of Jerusalem, defended orthodoxy and authored poetry and hagiographies. The leading hagiographer of the early 7th century, Bishop Leontios of Neapolis, wrote accessible saints' lives for the common people. In Constantinople, the scholar George Choiroboskos and physicians Paul of Aegina, Theophilus Protospatharius, and Stephen of Athens were active. Two chronicles from this period survive: Chronicle of the World by John of Antioch and the Paschal Chronicle.

In the late 7th century, the poet Andrew of Crete, a bishop, created numerous canons, including the renowned Great Canon. The theologian Anastasius Sinaita contributed to the final phase of the orthodoxy-Monothelitism debate. John of Nikiu authored a lost Chronicle of the World, and Trajan the Patrician wrote a Brief Chronicle. At the turn of the 8th century, the scholars Horapollo and his student Timothy of Gaza worked in Constantinople.

Remove ads

Decline of prominence

Summarize

Perspective

The reign of Heraclius (610–641) saw conflicts between the Byzantine Empire and Persia, culminating in Byzantine victory,[1] followed by the Arab conquest of Persia and significant Byzantine territories.[2] This era marked a decline in the brilliance of Byzantine literature, which had flourished in the preceding Justinianic period.[3] In the early 7th century, Theophylact Simocatta, a philosopher, rhetorician, and jurist who served as a high-ranking imperial official, was a singular historian without immediate successors. His History of the World, a continuation of Menander Protector's work, detailed the reign of Emperor Maurice (582–602). Written in a rhetorical, poetic style rich with allegories, dialogues, and sophisticated vocabulary, it was highly popular among Byzantine readers.[4] Simocatta also explored paradoxography in his youth with Quaestiones Physicae and wrote Ethical Epistles, blending historical, moral, and philosophical themes through the voices of historical figures, a work cherished by Byzantines.[5] Two chronicles from the early 7th century, written in vernacular Greek, are key sources for Heraclius' reign: Chronicle of the World by John of Antioch, composed between 610 and 631, and the slightly later Paschal Chronicle.[6]

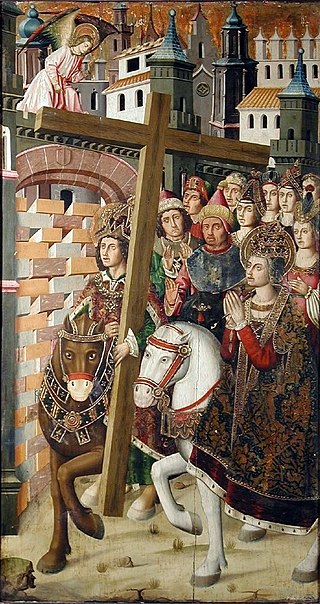

Associated with Heraclius and Patriarch Sergius, the eminent poet George of Pisidia, a deacon and chartophylax of Hagia Sophia, accompanied the emperor on campaigns.[7] His historical poems include The Official History of Heraclius' Persian Campaigns, On the Siege by Barbarians and Their Defeat, recounting the dramatic 626 siege of Constantinople by Avars, Persians, and Sclaveni, and Heraclias, celebrating Heraclius' victory over the Persian king Khosrow II at Nineveh in 627. He also penned shorter works, such as On the Recovery of the True Cross from the Persians by Emperor Heraclius and On Heraclius' Victory over Phocas.[8] Beyond historical poetry, George wrote philosophical-dogmatic poems, including the 1,894-verse Six Days of Creation, and numerous epigrams. His vivid, literary style earned widespread acclaim.[9] Another poet, Sophronius, Patriarch of Jerusalem from 634 to 638, composed 32 surviving Hymns, or Odes, in the Anacreontic style, focusing on episodes from Jesus' life. Maximus Margunius also wrote Anacreontic hymns.[10]

Sophronius was a theologian as well as a poet. He convened a synod in Jerusalem and sent a detailed synodal letter against Monothelitism to Patriarch Sergius. Nine of his homilies on various topics survive. His hagiographies include a detailed Life of Saints Cyrus and John, Egypt's foremost saints, Life of Saint John the Merciful, and Biography of Saint Mary of Egypt, a former sinner from Alexandria.[11] Hagiography also flourished under Leontios of Neapolis, Bishop of Cyprus (590–668), who broke with literary Greek to reach the common people with vernacular lives, including Life of Saint John the Merciful, Life of Symeon the Fool of Edessa, and Life of Saint Spyridon of Trimythous. Leontios also wrote numerous homilies and a five-book Dialogue Against the Jews.[12] Other hagiographic works from this period include Life of Saint Simeon Stylites the Younger by Arcadius, Bishop of Constantia in Cyprus; Life of George, a Palestinian hermit, by the monk Antonius; Life of Theodore of Sykeon by Gregory; Life of Theophanes the Confessor by the monk Nicephorus; and Collection of Miracles of Demetrius of Thessaloniki by John, Archbishop of Thessalonica.[13] The century's foremost theologian, Maximus the Confessor (580–662), initially an imperial official, later a monk, fiercely opposed the emperor-supported Monothelitism. Exiled to Lazica, he was mutilated by imperial order, losing his hand and tongue.[14][15] In To Maris, On the Soul, and Letters, he combated Monophysitism and Monothelitism. His five exegetical treatises and Catenae – anthologies of Church Fathers' biblical commentaries – are notable, as are his ascetic works: Chapters on Love, Dialogue on Asceticism, and Chapters on Knowledge. Maximus left approximately 500 letters on philosophical, theological, and historical topics, five dialogues on the Trinity, and commentaries on Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite and Gregory of Nazianzus.[13]

During Heraclius' reign, George Choiroboskos, a professor at Constantinople's Ecumenical School and chartophylax, was active. Student notes of his lectures explain Greek noun and verb conjugation. Surviving works include On Prosody, fragments of a commentary on Dionysius Thrax's Grammar, lectures on Greek versification, a student-recorded Commentary on Hephaestion's Manual, and an interpretation of Herodian's Onomatikon.[16][17] Physicians continued 6th-century advancements: Paul of Aegina compiled a six-book medical manual based on Aetius of Amida, Theophilus Protospatharius wrote On the Structure of the Human Body, and his student Stephen of Athens authored Commentary on Hippocrates' Prognostic and Commentary on Galen's Therapeutics.[18]

Remove ads

Later developments

Summarize

Perspective

The most prominent Byzantine author of the late 7th and early 8th centuries was Andrew of Crete (c. 660–740), a participant in the Sixth Ecumenical Council and bishop of Crete after 692. Andrew authored 50 homilies but gained fame as a poet, creating canons – choral hymns that replaced earlier kontakia in liturgy.[19] His canons, consisting of nine odes with three or more stanzas each, unified kontakia into a single hymn while preserving their thematic structure. His most famous work, the Great Canon, comprises 250 stanzas and is sung in full during the fifth week of Lent. Smaller canons include On the Conception of Anna, On the Nativity of the Mother of God, On Lazarus, and On Mid-Pentecost.[20]

In the late 7th century, John of Nikiû, a Monophysite bishop, wrote another Chronicle of the World, valuable for its account of the Arab conquest of Egypt in 642. At the turn of the century, Trajan the Patrician produced a lost Brief Chronicle, used by later chroniclers.[6] Also in the late 7th century, Anastasius Sinaita (640–700), a monk of the Saint Catherine's Monastery, emerged as the century's second major theologian after Maximus. His works include Guide against Monophysites, On Man Created in God's Image against Monothelites, and lost defenses of orthodoxy against Nestorians and Jews. These writings are key sources for the final stages of the orthodoxy-Monothelitism conflict. Anastasius also wrote an exegetical treatise, Creation of the World in Six Days, in 11 books, and several homilies.[21] During the reign of Emperor Theodosius III (715–717), the scholar Horapollo of Phaenebytis in Egypt, active in Alexandria and Constantinople, produced commentaries on Homer's poems, Sophocles's tragedies, and Alcaeus' lyric poetry. His student Timothy of Gaza wrote Common Patterns, a work on Greek syntax.[22]

Remove ads

References

Bibliography

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads