Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

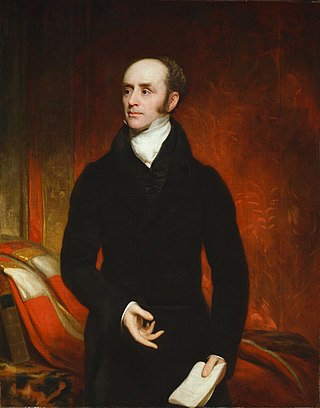

Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1830 to 1834 From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey (13 March 1764 – 17 July 1845) was a British Whig politician who served as prime minister of the United Kingdom from 1830 to 1834. His government enacted the Reform Acts of 1832, which expanded the electorate in the United Kingdom, and the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, which abolished slavery in the British Empire.

Born into a prominent family in Northumberland, Grey was educated at Eton College and the University of Cambridge. While travelling in Europe on a Grand Tour, his uncle secured his election as member of parliament (MP) for Northumberland in a 1786 by-election. Grey joined Whig circles in London and was a long-time leader of the reform movement. He briefly served as First Lord of the Admiralty and as foreign secretary in the Ministry of All the Talents from 1806 to 1807 and then remained in opposition for nearly 24 years. He was asked to form a ministry by William IV in 1830, following the resignation of Wellington.

As prime minister, Grey oversaw the passage of the Reform Act 1832, which redistributed parliamentary seats and standardised and extended the franchise in England and Wales. It was accompanied by the Scottish Reform Act and the Irish Reform Act of the same year. Grey's government also enacted the Slavery Abolition Act 1833, which outlawed the practice of slavery in the British Empire. Grey resigned as prime minister in 1834 following cabinet disagreements over policy in Ireland, and he subsequently retired from politics.

After an affair with the married Duchess of Devonshire, which resulted in a daughter who was brought up by Grey's parents, Grey married Mary Ponsonby and had fifteen children. His name is associated with Earl Grey tea although it is unlikely he had any connection with it.

Remove ads

Early life and education

Grey was born at Fallodon on 13 March 1764 into a landowning Northumberland family. He was the second, but eldest surviving, son of Charles Grey and Elizabeth Grey of County Durham. His father was a soldier who attained the rank of general and was elevated to the peerage as Baron Grey in 1801 and Earl Grey in 1806.[1] At the age of six, Grey was sent to a school in Marylebone, where he spent a miserable three years. He then went to Eton College, where he met future political allies, including Samuel Whitbread, and William Henry Lambton. He did not remember his time at Eton with great affection, and did not send his own sons there. George Heath, a master (and later headmaster) at Eton, recalled how Grey "was as he now is, able in his exercises, impetuous, overbearing &c...". In 1781, Grey went up to Trinity College, Cambridge, which was more congenial to him. He did not take a degree, which was not uncommon in those days.[2]: 8–9 At university, he acquired the skills in oratory that would distinguish him in Parliament.[1] Grey's education was completed by a Grand Tour, in which he travelled to southern France, Switzerland and Italy.[3]: 10–11

Remove ads

Member of Parliament, 1786-1806

Summarize

Perspective

During his childhood and youth, Grey had spent time with his unmarried uncle, Sir Henry Grey, at Howick Hall. In 1801, Grey and his family would take up residence at Howick Hall, and he inherited the estate when his uncle died in 1808.[1] Sir Henry, a baronet and former MP, managed to get his nephew elected in the Northumberland by-election of 1786.[2]: 9 Grey returned from his Grand Tour and took up his seat in the House of Commons in January 1787, aged 22.[3]: 11 While his father and uncle were supporters of the government of William Pitt, and he had been returned as the member for Northumberland without expressing any political allegiance, Grey soon entered Whig circles in London and became a follower of Charles Fox.[2]: 9-10 His maiden speech in February 1787 was an attack on Pitt's Commercial Treaty with France. The speech was greeted with applause; Henry Addington wrote: "I do not go too far in declaring that in the advantage of figure, voice, elocution, and manner, he is not surpassed by any member of the House" and lamented the fact that the speech had firmly placed Grey in the ranks of the opposition.[3]: 15 [2]: 17

In April 1792, Grey was one of the founders of the Society of the Friends of the People, a group of 147 people including 28 MPs and three peers that campaigned for parliamentary reform.[2]: 40 As a member of the committee who ran the society, Grey was careful to advocate moderation in calls for reform in order to distance themselves from the actions of French revolutionaries and to protect themselves from accusations of insurrection. The society’s manifesto said that its aim was to "reinstate the constitution upon its true principles" and indicated that Grey would move for reform in the next parliamentary session. On 6 May 1793, Grey duly moved that a petition of the society, which outlined the abuses of the electoral system and called for parliament "to regulate the right of voting upon a uniform and equitable principle", should be put before a parliamentary committee. Following a debate, the motion was defeated by 282 votes to 41, in spite of a supporting speech by Fox.[3]: 75-6 Grey, together with Fox and their supporters, also mounted challenges to the government's repressive measures against radicals, which culminated in the 1794 Treason Trials, and called for peace with France. In the 1796 general election Grey was returned unopposed.[4]

In May 1797, a second motion for electoral reform was lost by 256 votes to 91.[1] During the debate, both Grey and Fox indicated that, if the motion was not carried, they and their supporters would secede from parliament and only attend to vote on important measures.[3]: 96-7 The secession, which Grey came to regret, lasted about three years, leaving Grey free to return to Howick, where he and his wife lived as guests of his uncle.[3]: 103 In the 1799 session, he returned to parliament for the debates concerning Ireland, his marriage to Mary Ponsonby, who was from an Irish liberal family, having given his a particular interest in Irish affairs. By November 1800 he was participating more fully in debates in parliament, and was joined by Fox in March 1801.[3]: 104

In 1801, Grey's father accepted a peerage from the new prime minister Henry Addington and became Baron Grey, much to the dismay of Grey, as he had hoped to have a long career in the House of Commons rather than having to move to the House of Lords on inheriting the peerage.[3]: 146 That same year, Grey's uncle offered Howick as a permanent residence to Grey and his growing family.[3]: 108 Grey became increasingly attached to Howick and notoriously reluctant to make the journey to London to attend to political affairs.[3]: 111 When Pitt returned to power in 1804, he made approaches to Lord Grenville, who was by this time aligned with the Whigs, and Grey, who was now in support of the war against Napoleon following the breakdown of the peace of Amiens, to join a coalition government. Both refused to join the cabinet without Fox, and King George III was adamant that Fox could not be included, so the approaches came to nothing.[1]

Remove ads

Ministry of All the Talents, 1806–1807

Summarize

Perspective

The death of Pitt in January 1806 led to the formation of a new coalition of Whigs and Tories, led by Grenville and including Fox and Addington. It was dubbed the "ministry of all the talents" by George Canning, who was not part of it.[1] Grey was appointed Lord of the Admiralty, where he drew up proposals for increased pay for seamen and officers in the navy, as well as improvements at Greenwich Hospital and increases in navy pensions.[2]: 105 In April 1806, Grey's father was granted an earldom and Grey took the title Lord Howick. As it was a courtesy title, he was able to remain in the House of Commons.[1] On the death of Fox in September 1806, Grey became foreign secretary, leader of the House of Commons and leader of the Whigs.[3]: 149 Almost as soon as Grey became foreign secretary, the already faltering peace negotiations with Napoleon collapsed.[3]: 150

The ministry resigned on 15 March 1807 over the question of Catholic emancipation. Grey had introduced a bill to allow Catholics to hold commissions in the army but withdrew it following the king’s opposition. The king then asked ministers to pledge that they would not raise the issue of Catholic emancipation again. Rather than accept the king’s demand, the ministry resigned.[1] The last act of the ministry was to see the bill to abolish the slave trade through parliament. Grey delivered the principle speech in support of the bill in the House of Commons on 23 February 1807 and it was passed by 283 votes to 16. The Slave Trade Act 1807 received royal assent on 25 March 1807.[3]: 158-9

Opposition, 1807–1830

Summarize

Perspective

Following the resignation of Grenville's ministry in March 1807, the king asked the Duke of Portland to form a ministry and parliament was dissolved soon afterwards. Grey did not stand for election, as the Duke of Northumberland had put his son Earl Percy up for election and Grey could not afford the costs of a contested election.[3]: 161 He remained in parliament as Lord Thanet offered him his pocket borough of UK Parliament constituency, which he resigned in July 1807 in favour of the Duke of Bedford’s Tavistock. In November 1807, his father died and he was elevated to the House of Lords as the second Earl Grey.[3]: 162 His father's estate of Fallodon was inherited by his brother George, as Grey stood to inherit Howick from his uncle, who died in 1808.[1] The House of Lords was generally not well attended, and, with such a small audience, Grey's oratory had little impact.[3]: 163-4 After his first speech in the House of Lords in January 1808, he wrote despairingly to his wife that it was impossible he "should ever do anything there worth thinking of". Although he remained the leader of the Whigs during their spell of nearly twenty-four years in opposition, he did not maintain an active leadership and on more than one occasion offered to retire.

Without a strong leader in the House of Commons, the party became divided. Grey's brother-in-law Samuel Whitbread and his followers advocated peace with Napoleon, which the majority of the Whigs and Grenvillites disagreed with. In 1809, Grey refused to join Whitbread in his support of Mary Anne Clarke, who had brought charges of corruption against the Duke of York.[3]: 164-7 In September 1809, Spencer Perceval, with the king's permission, approached Grey and Grenville with a view to having them join his ministry. They rejected the offer. Further approaches were made by the prince regent in 1811 and 1812; they were likewise rejected. In November 1820, Grey made a powerful speech in support of Queen Caroline, having followed the proceedings in the House of Lords in which her husband, George IV, tried to divorce her. The speech led to the king harbouring an animosity against Grey and imposing a veto on him entering into government.[1] In 1829, Grey was largely responsible for seeing the bill for the Catholic Emancipation Act 1829, introduced by Wellington and Robert Peel, through the House of Lords.[1]

Remove ads

Prime minister, 1830–1834

Summarize

Perspective

Following the death of George IV and the accession of William IV in 1830, a general election was held in which the Duke of Wellington retained a majority. On 15 November 1830, the day before Henry Brougham was due to introduce a motion for reform, the government lost a vote on the civil list. Wellington resigned the following day and the king immediately asked Grey to form a ministry.[5][3]: 239-40 Grey took office on 22 November 1830 and put together his ministry. All but one of the thirteen members of his cabinet were peers or heirs to a peerage, while junior positions were awarded to members of his family, including his son Henry Grey, something that attracted the attention of the satirical print-makers of the day.[6]

The first cabinet meeting of the new administration was taken up with discussion of the Swing riots, agrarian disturbances in the south and east of the country.[2]: 263 The harsh suppression of the riots left what Trevelyan described as "as stain on the singularly pure reputation" of Grey, although it was Lord Melbourne who, as home secretary, was largely responsible for the measures.[3]: 252-3

The ministry next set about establishing the reform of parliament, which Grey had pledged when he came into power. In December 1830, a subcommittee of four cabinet members (Viscount Duncannon, Baron Durham, Sir James Graham, and Lord John Russell) was appointed to draw up a draft bill.[1] The report, with the king’s consent, was put before parliament as the first reform bill on 1 March 1831.[1][3]: 267 The bill passed its first reading in the House of Commons by only one vote. When an opposition amendment was passed by eight votes, Grey asked the king to dissolve parliament and call a general election.[1] The 1831 general election saw a resounding victory for the government, reflecting popular support for parliamentary reform. A second reform bill was passed in the House of Commons, but did not have a smooth passage in the House of Lords. In May 1832, the government threatened to resign unless the king would create new Whig peers to see the bill through. The king declined, accepted the resignation of Grey and his cabinet, and asked Wellington to form a ministry. In the face of public hostility and the refusal of Peel to join him, Wellington advised the king to recall Grey. He then withdrew his supporters from the House of Lords so that the bill could pass without the need to create additional peers. The Reform Act 1832 became law on 7 June 1832.[1] Similar acts followed for Ireland and Scotland, where, in addition, the Royal Burghs (Scotland) Act 1833 gave electors the right to elect town councils.[3]: 273

The Reform Act redistributed parliamentary seats in the boroughs by abolishing almost all the rotten and pocket boroughs and giving seats to towns which had previously had no representation, including industrial towns. The voting qualifications in the boroughs were standardised, giving voting rights to male occupiers of property (including offices, warehouses or shops as well as houses) with a rental value of at least £10 a year, provided they were resident ratepayers. In the counties, where the franchise had been based on a fifteenth century statute giving a vote to owners of land worth 40 shillings or more a year, the franchise was extended to copyholders of property with an annual rental value of at least £10, and £50 leaseholders. As a result of the act, the electorate in English boroughs increased by an estimated 61 per cent, while that of English counties increased by an estimated 29 per cent. The increase, however, was not consistent, and some boroughs and counties saw a decrease in the size of their electorate as a result of the act. Over England as a whole, there were 614,654 registered voters after the act.[7] The act enshrined in law the principle that only men could vote, while previously women had voted on very rare occasions. Most working class men were still excluded from the franchise.[8]

In 1831, the government passed the Truck Act 1831 (also known as the Money Payment of Wages Act), which prohibited the system of truck wages, where workers were paid in commodities rather than money. The bill had been introduced by Edward Littleton, MP for Staffordshire.[9]

The Slavery Abolition Act 1833 received royal assent in August 1833. Following on from the Slave Trade Act 1807 which had been passed by the previous Whig government in 1807, it made slavery illegal in the British Empire.[3]: 360 Grey's ministry also passed a Factory Act which put restrictions on the hours children could work in mills and established a factory inspectorate.[3]: 361 The Government of India Act 1833 ended the monopoly of the East India Company on trade with China and transformed it from a commercial to an administrative body. One clause specified that all offices within the Company should be open to natives of India regardless of religion or race.[3]: 360 Shortly before the end of Grey's ministry, the House of Commons passed the bill which became the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834. The New Poor Law was designed to impose harsh conditions on those in need of poor relief and reduce the cost of their maintenance to rate-payers. Parishes were formed into "unions", each with a workhouse. The able-bodied poor would no longer be afforded outdoor relief but be forced to enter the workhouse.[3]: 361-2

The cabinet suffered deep divisions over Irish affairs, which would eventually bring the ministry down. Lord Anglesey, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, preferred conciliatory reform, including the partial redistribution of the income from the tithes to the Catholic Church, and away from the established Church of Ireland, a policy known as "lay appropriation". The chief secretary for Ireland, Lord Stanley preferred coercive measures.[2]: 288-93 In May 1834 Stanley, along with three other members of the cabinet, resigned over the decision to appoint a Commission to enquire into the revenues of the Church of Ireland.[2]: 305 Grey no longer had the stamina to hold the fractured cabinet together, telling his wife that he felt "depressed and totally deprived of all energy and power, both physical and mental".[1] When Lord Althorp, chancellor of the exchequer and leader of the Whigs in the House of Commons, resigned in July 1834, Grey sent the king his own resignation.[1]

Remove ads

Retirement

Summarize

Perspective

Following his resignation, Grey attended numerous dinners and meetings held in his honour. A tour of Scotland in September included a dinner held in Edinburgh, where he made a speech in which he stressed the conservative nature of the Reform Act and called for future changes to be gradual "according to the increased intelligence of the people, and the necessities of the times".[2]: 309 Retiring to Howick, he at first kept up a keen interest in politics and the ministry Melbourne, who had replaced him as prime minister.[1] In April 1835, he declined an offer to return to government.[3]: 367

By the time he retired, only one of his children, Georgiana, was still at home, although the rest of his children and his grandchildren would return to Howick on long visits. Amongst friends who visited was Thomas Creevey, who left an account of evenings spent in conversation in the library or playing cribbage. In 1840, he attended the funeral procession of his son-in-law, the Earl of Durham. Grey’s final years were marred by ill health. He died on 17 July 1845 and was buried in Church of St Michael and All Angels in Howick. His widow survived him by sixteen years.[3]: 367-8 [1]

Remove ads

Personal life

Summarize

Perspective

Before his marriage, Grey had an affair with the married Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire, whom he met at Devonshire House. In 1791, the Duchess of Devonshire became pregnant with Grey's child, and she was sent to France, where, in February 1792, she gave birth to their daughter, Eliza Courtney, who was raised by Grey's parents at Fallodon.[1] Courtney married Robert Ellice.[10]

Marriage and children

On 18 November 1794, Grey married Mary Elizabeth Ponsonby (1776–1861), only daughter of William Ponsonby, 1st Baron Ponsonby of Imokilly and Louisa Molesworth.[11] They had the following 16 children:[12]

- a stillborn daughter (1796)[13]

- Louisa Elizabeth Grey (7 April 1797 – 26 November 1841). She married John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham, on 9 December 1816. They had five children, including Charles William, Grey's favourite grandson,[citation needed] who died young.

- Elizabeth Grey (10 July 1798 – 8 November 1880). She married John Crocker Bulteel on 13 May 1826. They had five children.

- Caroline Grey (30 August 1799 – 28 April 1875). She married Captain George Barrington on 15 January 1827. They had two children.

- Georgiana Grey (17 February 1801 – 13 September 1900)

- Henry George Grey, 3rd Earl Grey (28 December 1802 – 9 October 1894). He married Maria Copley on 9 August 1832.

- General Charles Grey (15 March 1804 – 31 March 1870). He married Caroline Farquhar on 26 July 1836. They had seven children, including Albert Grey, 4th Earl Grey.

- Admiral Sir Frederick William Grey (23 August 1805 – 2 May 1878). He married Barbarina Sullivan on 20 July 1846.

- Mary Grey (2 May 1807 – 6 July 1884). She married Charles Wood, 1st Viscount Halifax, on 29 July 1829. They had seven children.

- William Grey (13 May 1808 – 11 February 1815), who died at the age of six.

- Admiral George Grey (16 May 1809 – 3 October 1891). He married Jane Stuart (daughter of General Sir Patrick Stuart) on 20 January 1845. They had eleven children.

- Thomas Grey (29 December 1810 – 8 July 1826), who died at the age of fifteen.

- Rev. John Grey MA, DD (2 March 1812 – 11 November 1895), Canon of Durham, Rector of Houghton-le-Spring. He married Lady Georgiana Hervey (daughter of Frederick William Hervey, 1st Marquess of Bristol) in July 1836. They had three children. He remarried Helen Spalding (maternal granddaughter of John Henry Upton, 1st Viscount Templetown) on 11 April 1874.

- Rev. Francis Richard Grey MA (31 March 1813 – 22 March 1890), Hon. Canon of Newcastle, Rector of Morpeth. He married Lady Elizabeth Dorothy Anne Howard, daughter of George Howard, 6th Earl of Carlisle on 12 August 1840.

- Captain Henry Cavendish Grey (16 October 1814 – 5 September 1880)

- William George Grey (15 February 1819 – 19 December 1865). He married Theresa Stedink on 20 September 1858.

Remove ads

Legacy

Grey's biographer G. M. Trevelyan says: "In our domestic history 1832 is the next great landmark after 1688 ... [It] saved the land from revolution and civil strife and made possible the quiet progress of the Victorian era..."[14]

Grey is commemorated by Grey's Monument in the centre of Newcastle upon Tyne, which consists of a statue of Grey standing atop a 40 m (130 ft) high column.[15] The monument was struck by lightning in 1941 and the statue's head was knocked off.[16] Grey Street in Newcastle upon Tyne, which runs south-east from the monument, is also named after Grey.[17]

Durham University's Grey College is named after Grey, who supported the Act of Parliament that established the university in 1832.[18]

Grey has been associated with Earl Grey tea, a bergamot-flavoured blend, but it is unlikely he was the origin of the name.[19]

Remove ads

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads