Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Chlamydia (bacterium)

Genus of bacteria From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Chlamydia is a genus of pathogenic Gram-negative bacteria that are obligate intracellular parasites. Chlamydia infections are the most common bacterial sexually transmitted diseases in humans and are the leading cause of infectious blindness worldwide.[4]

Humans mainly contract C. trachomatis, C. pneumoniae, C. abortus, and C. psittaci.[5]

Remove ads

Classification

Summarize

Perspective

Because of Chlamydia's unique developmental cycle, it was taxonomically classified in a separate order.[6] Chlamydia is part of the order Chlamydiales, family Chlamydiaceae.[1]

Chlamydophila (1999–2009)

Earlier criteria for differentiation of chlamydial species did not always work well. For example, at that time C. psittaci was distinguished from C. trachomatis by sulfadiazine resistance, although not all strains identified as C. psittaci at the time were resistant, and C. pneumoniae was classified by its appearance under electron microscopy (EM) and its ability to infect humans, although the EM appearance may differ from one research group to the next, and many of these species infected humans.

A major re-description of the Chlamydiales order in 1999, using the then-new techniques of DNA analysis split three of the species from the genus Chlamydia and reclassified them in the then newly created genus Chlamydophila (Cp. hereafter). Five new species were added by splitting from existing species:[7]

According to the authors of the 1999 study, the mean DNA–DNA reassociation difference distinguishing Chlamydophila from Chlamydia is 10.1%, an accepted value for genus separation. Although the 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequences of the two are close to 95% identical, unlike the other previously established genera, the authors considered a less than 95% similarity only a guideline for establishing new genera in chlamydial families. In the study, the authors used the similarity of the locations of coding for protein and ribosomal RNA genes in the genome (gene clusters) to help distinguish Chlamydophila from Chlamydia. Also, the full-length 23S ribosomal RNA genes of the species of the two genera were less than 95% identical.[7] Supporting criteria such as antigen detection,[9] glycogen staining, host association, and EM morphology were also employed, depending on applicability and availability.

In 2001 many bacteriologists strongly objected to the reclassification.[1] Comparative genomic analyses in 2006 identified a number of signature proteins that were uniquely present in species from the genera Chlamydia and Chlamydophila, which supported the distinctness of Chlamydophila, but did not support an "early separation" scenario as suggested by rRNA.[10]

In 2009 the validity of Chlamydophila was challenged by newer DNA analysis techniques (using 100 concatenated proteins instead of 16S rRNA), leading to a proposal to "reunite the Chlamydiaceae into a single genus, Chlamydia". The authors pointed to the poor bootstrap support of the 1999 rRNA tree, which demonstrated a split in only 68% of the sampled trees, and argued that the 2006 study did not provide sufficiently strong support for the separation.[11] This reversion appears to have been accepted by the community[12] and was formally validated in 2015,[13][14] bringing the number of (valid) Chlamydia species up to 9 as of 2017.[15] The merger of the genus Chlamydophila back into the genus Chlamydia is, by 2018, generally accepted.[16][17][18][19]

However, the much newer analyses of Genome Taxonomy Database using 120 concatenated proteins again show a split of those two genera to be valid (see § Phylogeny below), and has led to the resurrection of the genus in the GTDB and GBIF taxonomies.[20][21] Joseph et al. 2015, which proposed new species from strains formerly known as C. psittaci, also recovered a coherent Chlamydophila clade in their whole-genome tree, but with an unusual topology showing Chlamydophila to be sister to C. muridarum.[5] Gupta et al. (2015) finds 1 CSI + 19 CSPs specific for Chlamydophilia and 2 CSIs + 19 CSPs specific for the three-species version of Chlamydia.[22]

Species additions

Many probable species were subsequently isolated, but no one bothered to name them. Many new species fall into the Chlamydophilia clade and were originally classified as aberrant strains of C. psittaci. Complicating the picture is the fact that this clade shows signs of interspecies recombination.[5]

- In 2013 a 10th species was added, C. ibidis, known only from feral sacred ibis in France.[23]

- Two more species were added in 2014 (but validated 2015): C. avium which infects pigeons and parrots, and C. gallinacea infecting chickens, guinea fowl and turkeys.[5]

- Two of the species proposed for Chlamydophila in 1999 (C. abortus, C. felis) were formally merged in 2015.[1] C. caviae was covered by the same publication, but was only validated in 2024.[24]

- C. poikilotherma was validated in 2022, as a correction of the 2019 "Chlamydia poikilothermis".[1]

- C. buteonis was validated in 2023.[1]

- C. crocodili was validated in 2023.[1]

There is one invalidly published Chlamydophilia species that has not been transferred back to Chlamydia as of 2025: "Chlamydophila parapsittaci",[25] representative of an intermediate stage between C. abortus and C. psittaci.[26] See Chlamydia psittaci § Psittaci-abortus intermediate for a discussion of it.

Remove ads

Genomes

Chlamydia species have genomes around 1.0–1.3 megabases in length.[27] Most encode ≈900~1050 proteins.[28] Some species also contain a DNA plasmids or phage genomes (see Table 1, below). The elementary body contains an RNA polymerase responsible for the transcription of the DNA genome after entry into the host cell cytoplasm and the initiation of the growth cycle. Ribosomes and ribosomal subunits are found in these bodies.[29]

MoPn is a mouse pathogen while [†] strain "D" is a human pathogen. About 80% of the genes in C. trachomatis and C. pneumoniae are orthologs. Adapted after Read et al. 2000,[28] nomenclature of MoPn following Carlson et al. 2008.[30]

Remove ads

Developmental cycle

Summarize

Perspective

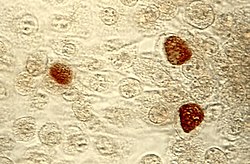

Chlamydia may be found in the form of an elementary body and a reticulate body. The elementary body is the nonreplicating infectious particle that is released when infected cells rupture. It is responsible for the bacteria's ability to spread from person to person and is analogous to a spore. The elementary body may be 0.25 to 0.30 μm in diameter. This form is covered by a rigid cell wall (hence the combining form chlamyd- in the genus name). The elementary body induces its own endocytosis upon exposure to target cells. One phagolysosome usually produces an estimated 100–1000 elementary bodies.[citation needed]

Chlamydia may also take the form of a reticulate body, which is in fact an intracytoplasmic form, highly involved in the process of replication and growth of these bacteria. The reticulate body is slightly larger than the elementary body and may reach up to 0.6 μm in diameter with a minimum of 0.5 μm. It does not have a cell wall. When stained with iodine, reticulate bodies appear as inclusions in the cell. The DNA genome, proteins, and ribosomes are retained in the reticulate body. This occurs as a result of the development cycle of the bacteria. The reticular body is basically the structure in which the chlamydial genome is transcribed into RNA, proteins are synthesized, and the DNA is replicated. The reticulate body divides by binary fission to form particles which, after synthesis of the outer cell wall, develop into new infectious elementary body progeny. The fusion lasts about three hours and the incubation period may be up to 21 days. After division, the reticulate body transforms back to the elementary form and is released by the cell by exocytosis.[6]

Studies on the growth cycle of C. trachomatis and C. psittaci in cell cultures in vitro reveal that the infectious elementary body (EB) develops into a noninfectious reticulate body (RB) within a cytoplasmic vacuole in the infected cell. After the elementary body enters the infected cell, an eclipse phase of 20 hours occurs while the infectious particle develops into a reticulate body. The yield of chlamydial elementary bodies is maximal 36 to 50 hours after infection.[29]

A histone like protein HctA and HctB play role in controlling the differentiation between the two cell types. The expression of HctA is tightly regulated and repressed by small non-coding RNA, IhtA until the late RB to EB re-differentiation.[31] The IhtA RNA is conserved across Chlamydia species.[32]

Remove ads

Pathology

Most chlamydial infections do not cause symptoms.[33] Symptomatic infections often include a burning sensation when urinating and abdominal or genital pain and discomfort.[34] All people who have engaged in sexual activity with potentially infected individuals may be offered one of several tests to diagnose the condition.[citation needed] Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT), which include polymerase chain reaction (PCR), transcription-mediated amplification (TMA), ligase chain reaction (LCR), and strand displacement amplification (SDA), are the most widely used diagnostic test for Chlamydia.[35]

Remove ads

Evolution

Phylogeny

Summarize

Perspective

| 16S rRNA based LTP_10_2024[36][37][38] | 120 marker proteins based GTDB 09-RS220[39][40][41] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Remove ads

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads