Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

City University of New York

Public university system in New York City, New York, United States From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The City University of New York (CUNY, pronounced /ˈkjuːni/, KYOO-nee) is the public university system of New York City. It is the largest urban university system in the United States, comprising 25 campuses: eleven senior colleges, seven community colleges, and seven professional institutions. The university enrolls more than 275,000 students. CUNY alumni include thirteen Nobel Prize winners and twenty-four MacArthur Fellows.

The oldest constituent college of CUNY, City College of New York, was originally founded in 1847 and became the first free public institution of higher learning in the United States.[8] In 1960, John R. Everett became the first chancellor of the Municipal College System of New York City, later known as the City University of New York (CUNY). CUNY, established by New York state legislation in 1961 and signed into law by Governor Nelson Rockefeller, was an amalgamation of existing institutions and a new graduate school.

The system was governed by the Board of Higher Education of the City of New York, created in 1926, and later renamed the Board of Trustees of CUNY in 1979. The institutions merged into CUNY included the Free Academy (later City College of New York), the Female Normal and High School (later Hunter College), Brooklyn College, and Queens College. CUNY has historically provided accessible education, especially to those excluded or unable to afford private universities. The first community college in New York City was established in 1955 with shared funding between the state and the city, but unlike the senior colleges, community college students had to pay tuition.

The integration of CUNY's colleges into a single university system took place in 1961, under a chancellor and with state funding. The Graduate Center, serving as the principal doctorate-granting institution, was also established that year. In 1964, Mayor Robert F. Wagner Jr. extended the senior colleges' free tuition policy to community colleges. The 1960s saw student protests demanding more racial diversity and academic representation in CUNY, leading to the establishment of Medgar Evers College and the implementation of the Open Admissions policy in 1970. This policy dramatically increased student diversity but also introduced challenges like low retention rates. The 1976 fiscal crisis ended the free tuition policy, leading to the introduction of tuition fees for all CUNY colleges.

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

19th-century

Social context

Historians Willis Rudy and Harry Noble Wright identify the historical trends leading to the foundation of the Free Academy as the result of "the growing democratization of American life" and rapid urban development and its cultural implications. They note that "the birth of the Free Academy in the metropolis of the New World came at the very time that European revolutionists were struggling for freedom and democracy in the Old."[9] In the mid-19th century, free elementary and high schools sprouted up all across the country in "an educational renaissance" borne of organized labor, the expansion of suffrage, and industrialization. New York City, a booming metropolis and predominant seaport in the Western hemisphere, was uniquely situated to forge ambitious educational initiatives. The first free denominational schools were established on Manhattan Island in 1633; a system of secular schools was established in 1805.[9] From 1825 to 1860, New York City's population rose from 166,000 residents to 814,000, making it the third largest city in the Western world. Though a number of newcomers were mercantilists from New England drawn to the advantages of New York's harbor, "in the decades prior to the Civil War the farms of Ireland and the villages of Germany were the chief sources of New York's newcomers."[9]

Debates on the Free Academy

On March 15, 1847, Townsend Harris, then president of the city's Board of Education and later the first United States Consul General to Japan, published a letter in The Morning Courier and New York Enquirer that proposed a free public school where the children of the poor would have the possibility of advancement:

No, Sirs, the system now pursued by that excellent society and by our ward schools is the true one, and may be advantageously applied to higher seminaries of learning. Make them the property of the people - open the doors to all - let the children of the rich and the poor take their seats together and know of no distinction save that of industry, good conduct, and intellect. A large number of the children of the rich now attend our public schools, and the ratio is rapidly increasing.

This experiment would later be called "the first successful experiment in the western hemisphere of one of the great ideals of democracy, free, higher education for the masses." This was not without debate, hashed out in the newspapers of the day. Two of Harris's supporters, James Gordon Bennett and William Cullen Bryant, were the editors of the Herald and the Evening Post, respectively, and chimed in with their support in their editorial pages. Horace Greeley, founder and editor of the publication the New-York Tribune and later a member of the Board of Education opposed the use of public funds for the school, although he supported the overall mission.Greeley would continue to call for the abolition of the school well into its founding. The Free Academy received its charter from the New York State Legislature on May 7, 1847. Harris was succeeded as President of the Board of Education by Robert Kelley, and construction of The Free Academy began in November 1847. Dr. Horace Webster, a graduate of the United States Military Academy and professor of mathematics was chosen by Kelly and his committee as the school's first principal. At the formal opening on January 21, 1849, Webster outlined the intention of the academy:

The experiment is to be tried, whether the children of the people, the children of the whole people, can be educated; and whether an institution of the highest grade, can be successfully controlled by the popular will, not by the privileged few.

The Free Academy was the "first municipal institution for free higher education to appear on this globe."[10] The Free Academy was renamed the College of the City of New York in 1866 in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, at the behest of students who felt that the name "Academy" did not carry the same prestige in the world as "College" did.

Founding of Hunter College

The next school to be established that would eventually come under the purview of CUNY was the Normal College. Normal schools, or institutions for teacher education, were first established in New York in 1834, with schools for white men, white women, and women of color. However, there were inequities as the women's schools were only open on Saturdays; there was also a lack of attention to teaching skills, with the female curriculum limited to mathematics.[11] The first state normal school for teacher instruction was established in Albany, New York on May 7, 1844, now the University of Albany. This was followed by the establishment of a number of other normal schools. In 1851, the state legislature sought to "amend, consolidate, and reduce to one act, the various acts relative to the Common Schools of the city of New York," and formalized a board of education for the city.[12] with the mission of continuing to "furnish through the free academy, the benefit of education, gratuitously, to persons who have been pupils in the common schools of the said city and county, for a period of time to be regulated by the board of education not less than one year." This included a mandate for the formation of new schools, including evening schools. The call for the establishment of a normal school for women in New York City was reiterated in 1854, and once more tied directly to the founding of the Free Academy just five years prior. In 1854 the state legislature amended the act of 1851 to grant the Board of Education power

to continue the existing Free Academy, and organize a similar institution for females, and if any similar institution is organized by the board of education, all the provisions of this act, relative to the Free Academy, shall apply to each and every one of the said institutions, as fully, completely, and distinctly as they could or would if it was the only institution of the kind.[13]

In 1868 the Board of Education once more called for the establishment of a female institution of higher education, and on November 13, 1869 the Committee on Normal, Evening and Colored Schools adopted a resolution establishing a daily Female Normal and High School.[14] The Female Normal and High School was opened on February 14, 1870 on the third floor of a building at the southeast corner of Broadway and Fourth Street.[13] The school was established by Irish schoolmaster and exiled republican Thomas Hunter as a normal school, who "insisted on admitting students of all racial and ethnic backgrounds and teaching a combined curriculum of liberal arts, science, and education."[15] The school's name was shortly changed to Normal College and in September 1873 moved into a Gothic revivalist building designed by Hunter himself, between 68th and 69th Street on Park Avenue. A broad curriculum encompassing both the humanities and the sciences was implemented, and in the following decades the school expanded its focus from solely teacher education, opening academic departments (though these still included in the methods and history of pedagogy).[13]

20th-century

The College of the City of New York

In 1903, John Huston Finley became President of City College, succeeding Alexander Stewart Webb. In 1906, Thomas Hunter retired, and the first stirrings of the merger of the colleges began. A highly debated coeducational proposal suggested a merger of the Normal College with the College of the City of New York. The Normal College opposed this measure. In 1908, George Samler Davis became the official second president of the Normal College; under his administration the college curriculum was liberalized to include electives, following the model Harvard was then introducing.[13] In 1914, the Normal College would be renamed Hunter College to honor of its founder, and also to clarify the nature of its mission; its name implied that it was a technical or professional school, but since as early as 1888 it had granted degrees and diplomas in the arts.[13] The school was constantly expanding, and the increased number of students and issues of overcrowding led to the creation of a Board of Trustees in 1915. There were branches established in Brooklyn, Queens, and Staten Island. Enrollment had increased from 3,871 in 1900, to approximately 23,089 by 1930. In 1926, a Board of Higher Education was established to manage the expansion of the colleges.

Brooklyn College was founded in 1930 in a merger of the Brooklyn branches of Hunter College and the City College of New York.[16]

Social context

CUNY has served a diverse student body, especially those excluded from or unable to afford private universities. Its four-year colleges offered a high-quality, tuition-free education to the poor, the working class, and the immigrants of New York City who met the grade requirements for matriculated status. During the post-World War I era, when some Ivy League universities, such as Yale and Columbia, discriminated against Jews, many Jewish academics and intellectuals studied and taught at CUNY.[17] The City College of New York developed a reputation of being "the Harvard of the proletariat."[18][19][20][21][22]

As New York City's population and public college enrollment continued to grow during the early 20th century and the city struggled for resources, the municipal colleges slowly began adopting selective tuition, also known as instructional fees, for a handful of courses and programs. During the Great Depression, with funding for public colleges severely constrained, limits were imposed on the size of the colleges' free Day Sessions, and tuition was imposed upon students deemed "competent" but not academically qualified for the day program. Most of these "limited matriculation" students enrolled in the Evening Sessions, and paid tuition.[23] Additionally, as the population of New York grew, CUNY was not able to accommodate the demand for higher education. Higher and higher requirements for admission were imposed; by 1965, a student seeking admission to CUNY needed an average grade of 92 or A−.[24] This helped to ensure that the student population of CUNY remained largely white and middle-class.[24]

There is a long tradition of student activism at CUNY. Eastern European Jewish refugees made City College a "hotbed of antifascism" in the early 20th century.[25] On April 13, 1934, City and Hunter Colleges were sites of a National Student Strike Against War, organized by the Student League for Industrial Democracy and the National Student League. At City College, approximately 600 students gathered at the flagpole on campus to protest the war, as well as demand the reinstatement of twenty-one students[26] who had been expelled for refusing to answer Dean Morton Gottschall's questions regarding their actions in a prior protest against a visiting delegation of soldiers from fascist Italy on October 9.[27] At Hunter College, the students demonstrated against then-president Dr. Eugene A. Colligan for his refusal to cooperate with the nationwide anti-war strike "and especially his attempt to call a halt to an anti-war convention at Hunter College on mere technicalities."[28] On November 20, 1934, nearly 1,500 gathered at the CCNY Quad to protest the expulsion, culminating in the burning of a two-headed effigy of CCNY President Robinson and Italian Prime Minister Benito Mussolini.[29] After the rally, more than 2,000 City College students voted to reinstate the twenty-one students, this time advocating "a 'legal method' of struggle...as opposed to the holding of unauthorized demonstrations."[30]

Demand in the United States for higher education rapidly grew after World War II, and during the mid-1940s a movement began to create community colleges to provide accessible education and training. In New York City, however, the community college movement was constrained by many factors including "financial problems, narrow perceptions of responsibility, organizational weaknesses, adverse political factors, and other competing priorities."[31]

Municipal college expansion

Community colleges would have drawn from the same city coffers that were funding the senior colleges, and city higher education officials were of the view that the state should finance them. It was not until 1955, under a shared-funding arrangement with New York State, that New York City established its first community college, on Staten Island. Unlike the day college students attending the city's public baccalaureate colleges for free, community college students had to pay tuition fees under the state-city funding formula. Community college students paid tuition fees for approximately 10 years.[31]

Over time, tuition fees for limited-matriculated students became an important source of system revenues. In fall 1957, for example, nearly 36,000 attended Hunter, Brooklyn, Queens and City Colleges for free, but another 24,000 paid tuition fees of up to $300 a year ($3,400 in current dollar terms).[32] Undergraduate tuition and other student fees in 1957 comprised 17 percent of the colleges' $46.8 million in revenues, about $7.74 million ($86,650,000 in current dollar terms).[33]

The municipal college system becomes CUNY

In 1960, John R. Everett became the first chancellor of the Municipal College System of the City of New York, later renamed CUNY, for a salary of $25,000 ($266,000 in current dollar terms).[34][35][36] CUNY was created in 1961,[37] by New York State legislation, signed into law by Governor Nelson Rockefeller. The legislation integrated existing institutions and a new graduate school into a coordinated system of higher education for the city, under the control of the "Board of Higher Education of the City of New York", which had been created by New York State legislation in 1926. By 1979, the Board of Higher Education had become the "Board of Trustees of the CUNY".[38]

The institutions that were merged to create CUNY were:[38]

- The Free Academy – Founded in 1847 by Townsend Harris, it was fashioned as "a Free Academy for the purpose of extending the benefits of education gratuitously to persons who have been pupils in the common schools of the city and county of New York." The Free Academy later became the City College of New York.

- The Female Normal and High School – Founded in 1870, and later renamed the Normal College. It would be renamed again in 1914 to Hunter College. During the early 20th century, Hunter College expanded into the Bronx, with what became Herbert Lehman College.[38]

- Brooklyn College – Founded in 1930.

- Queens College – Founded in 1937.

Three community colleges had been established by early 1961 when New York City's public colleges were codified by the state as a single university with a chancellor at the helm and an infusion of state funds. But the city's slowness in creating the community colleges as demand for college seats was intensifying and had resulted in mounting frustration, particularly on the part of minorities, that college opportunities were not available to them.

In 1964, as New York City's Board of Higher Education moved to take full responsibility for the community colleges, city officials extended the senior colleges' free tuition policy to them, a change that was included by Mayor Robert F. Wagner Jr. in his budget plans and took effect with the 1964–65 academic year.[39]

Open admissions struggle

Calls for greater access to public higher education from the black and Puerto Rican communities in New York, especially in Brooklyn, led to the founding of "Community College Number 7," later Medgar Evers College, in 1966–1967.[24] In 1969, a group of black and Puerto Rican students occupied City College and demanded the racial integration of CUNY, which at the time had an overwhelmingly white student body.[31]

Students at some campuses became increasingly frustrated with the university's and Board of Higher Education's handling of university administration. At Baruch College in 1967, over a thousand students protested the plan to make the college an upper-division school limited to junior, senior, and graduate students.[40] At Brooklyn College in 1968, students attempted a sit-in to demand the admission of more black and Puerto Rican students and additional black studies curriculum.[41] Students at Hunter College also demanded a Black studies program.[42] Members of the SEEK program, which provided academic support for underprepared and underprivileged students, staged a building takeover at Queens College in 1969 to protest the decisions of the program's director, who would later be replaced by a black professor.[43][44] Puerto Rican students at Bronx Community College filed a report with the New York State Division of Human Rights in 1970, contending that the intellectual level of the college was inferior and discriminatory.[45] Hunter College was crippled for several days by a protest of 2,000 students who had a list of demands focusing on more student representation in college administration.[46] Across CUNY, students boycotted their campuses in 1970 to protest a rise in student fees and other issues, including the proposed (and later implemented) open admissions plan.[47]

Under pressure from community activists and CUNY Chancellor Albert Bowker, the Board of Higher Education (BHE) approved an open admissions plan in 1966, but it was not scheduled to be fully implemented until 1975.[24] In 1969, students and faculty across CUNY participated in rallies, student strikes, and class boycotts demanding an end to CUNY's restrictive admissions policies. CUNY administrators and Mayor John Lindsay expressed support for these demands, and the BHE voted to implement the plan immediately in the fall of 1970.[24]

All high school graduates were guaranteed entrance to the university without having to fulfill traditional requirements such as exams or grades. The policy nearly doubled the number of students enrolled in the CUNY system to 35,000 (compared to 20,000 the year before). Black and Hispanic student enrollment increased threefold.[48] Remedial education, to supplement the training of under-prepared students, became a significant part of CUNY's offerings.[49] Additionally, ethnic and Black Studies programs and centers were instituted on many CUNY campuses, contributing to the growth of similar programs nationwide.[24]

Retention of students in CUNY during this period was low; two-thirds of students enrolled in the early 1970s left within four years without graduating.[24]

Fear City: CUNY in the 1970s

Like many college campuses in 1970, CUNY faced a number of protests and demonstrations after the Kent State massacre and Cambodian Campaign. The Administrative Council of the City University of New York sent U.S. president Richard Nixon a telegram in 1970 stating, "No nation can long endure the alienation of the best of its young people."[50] Some colleges, including John Jay College of Criminal Justice, historically the "college for cops," held teach-ins in addition to student and faculty protests.[51]

In fall 1976, during New York City's fiscal crisis, the free tuition policy was discontinued under pressure from the federal government, the financial community that had a role in rescuing the city from bankruptcy, and New York State, which would take over the funding of CUNY's senior colleges.[52] Tuition, which had been in place in the State University of New York system since 1963, was instituted at all CUNY colleges.[53][54]

Meanwhile, CUNY students were added to the state's need-based Tuition Assistance Program (TAP), which had been created to help private colleges.[55] Full-time students who met the income eligibility criteria were permitted to receive TAP, ensuring for the first time that financial hardship would deprive no CUNY student of a college education.[55] Within a few years, the federal government would create its own need-based program, known as Pell Grants, providing the neediest students with a tuition-free college education.

Austerity and the end of open admissions

Joseph S. Murphy was Chancellor of the City University of New York from 1982 to 1990, when he resigned.[56] CUNY at the time was the third-largest university in the United States, with over 180,000 students.[57] CUNY's enrollment dipped after tuition was re-established, and there were further enrollment declines through the 1980s and into the 1990s.[58] Joseph S. Murphy was Chancellor of the City University of New York from 1982 to 1990, when he resigned.[56] CUNY at the time was the third-largest university in the United States, with over 180,000 students.[57]

In 1995, CUNY suffered another fiscal crisis when Governor George Pataki proposed a drastic cut in state financing.[59] Faculty cancelled classes and students staged protests. By May, CUNY adopted deep cuts to college budgets and class offerings.[60] By June, to save money spent on remedial programs, CUNY adopted a stricter admissions policy for its senior colleges: students deemed unprepared for college would not be admitted, this a departure from the 1970 Open Admissions program.[61] That year's final state budget cut funding by $102 million, which CUNY absorbed by increasing tuition by $750 and offering a retirement incentive plan for faculty.

In 1999, a task force appointed by Mayor Rudolph Giuliani issued a report that described CUNY as "an institution adrift" and called for an improved, more cohesive university structure and management, as well as more consistent academic standards. Following the report, Matthew Goldstein, a mathematician and City College graduate who had led CUNY's Baruch College and briefly, Adelphi University, was appointed chancellor. CUNY ended its policy of open admissions to its four-year colleges, raised its admissions standards at its most selective four-year colleges (Baruch, Brooklyn, City, Hunter and Queens), and required new enrollees who needed remediation to begin their studies at a CUNY open-admissions community college.[62]

21st Century

CUNY's enrollment of degree-credit students reached 220,727 in 2005 and 262,321 in 2010 as the university broadened its academic offerings.[63] The university added more than 2,000 full-time faculty positions, opened new schools and programs, and expanded the university's fundraising efforts to help pay for them.[62] Fundraising increased from $35 million in 2000 to more than $200 million in 2012.[64]

By 2011, nearly six of ten full-time undergraduates qualified for a tuition-free education at CUNY due in large measure to state, federal and CUNY financial aid programs.[65]

By autumn 2013, all CUNY undergraduates were required to take an administration-dictated common core of courses that have been claimed to meet specific "learning outcomes" or standards. Since the courses are accepted university-wide, the administration claims it will be easier for students to transfer course credits between CUNY colleges. It also reduced the number of core courses some CUNY colleges had required, to a level below national norms, particularly in the sciences.[66][67] The program is the target of several lawsuits by students and faculty, and was the subject of a "no confidence" vote by the faculty, who rejected it by an overwhelming 92% margin.[68]

Chancellor Goldstein retired on July 1, 2013, and was replaced on June 1, 2014, by James Milliken, president of the University of Nebraska, and a graduate of the University of Nebraska–Lincoln and New York University School of Law.[69] Milliken retired at the end of the 2018 academic year and moved on to become the chancellor for the University of Texas system.[70][71]

In 2018, CUNY opened its 25th campus, the CUNY School of Labor and Urban Studies, named after former president Joseph S. Murphy and combining some forms and functions of the Murphy Institute that were housed at the CUNY School of Professional Studies.[72]

On February 13, 2019, the board of trustees voted to appoint Queens College president Felix V. Matos Rodriguez as the chancellor of the City University of New York.[73] Matos became both the first Latino and minority educator to head the university. He assumed the post May 1.[74]

In April 2024, CUNY students joined other campuses across the United States in protests against the Israel–Hamas war.[75] The student protestors demanded that CUNY divest from companies with ties to Israel and that CUNY officials cancel any upcoming trips to Israel and protect students involved in the demonstrations.[76] In 2025, CUNY terminated four professors and one student leader for their opposition to the Gaza war.[77][78]

Remove ads

Enrollment and demographics

Summarize

Perspective

CUNY is the fourth-largest university system in the United States by enrollment, behind the California State University, State University of New York (SUNY), and University of California systems. More than 271,000-degree-credit students, continuing, and professional education students are enrolled at campuses located in all five New York City boroughs.[79]

The university has one of the most diverse student bodies in the United States, with students hailing from around the world, although most students live in New York City. The black, white and Hispanic undergraduate populations each comprise more than a quarter of the student body, and Asian undergraduates make up 18 percent. Fifty-eight percent are female, and 28 percent are 25 or older.[80] In the 2017–2018 award year, 144,380 CUNY students received the Federal Pell Grant.[81]

CUNY Citizenship Now!

Founded in 1997 by immigration lawyer Allan Wernick, CUNY Citizenship Now! is an immigration assistance organization that provides free and confidential immigration law services to help individuals and families on their path to U.S. citizenship.[82][83] In 2021, CUNY launched a College Immigrant Ambassador Program in partnership with the New York City Department of Education.[84][85]

Remove ads

Academics

This section needs expansion with: (see articles for similar U.S. schools). You can help by adding to it. (June 2020) |

Component institutions

Remove ads

Management structure

Summarize

Perspective

This section contains close paraphrasing of a copyrighted source, https://www.cuny.edu/about/trustees/history/ (Copyvios report). (August 2024) |

The forerunner of today's City University of New York was governed by the Board of Education of New York City. Members of the Board of Education, chaired by the president of the board, served as ex officio trustees. For the next four decades, the board members continued to serve as ex officio trustees of the College of the City of New York and the city's other municipal college, the Normal College of the City of New York.

In 1900, the New York State Legislature created separate boards of trustees for the College of the City of New York and the Normal College, which became Hunter College in 1914. In 1926, the legislature established the Board of Higher Education of the City of New York, which assumed supervision of both municipal colleges.

In 1961, the New York State Legislature established the City University of New York, uniting what had become seven municipal colleges at the time: the City College of New York, Hunter College, Brooklyn College, Queens College, Staten Island Community College, Bronx Community College and Queensborough Community College. In 1979, the CUNY Financing and Governance Act was adopted by the State and the Board of Higher Education became the City University of New York board of trustees.

Today, the City University is governed by the board of trustees composed of 17 members, ten of whom are appointed by the governor of New York "with the advice and consent of the senate," and five by the mayor of New York City "with the advice and consent of the senate." The final two trustees are ex officio members. One is the chair of the university's student senate, and the other is non-voting and is the chair of the university's faculty senate. Both the mayoral and gubernatorial appointments to the CUNY Board are required to include at least one resident of each of New York City's five boroughs. Trustees serve seven-year terms, which are renewable for another seven years. The chancellor is elected by the board of trustees, and is the "chief educational and administrative officer" of the City University.

The administrative offices are in Midtown Manhattan.[87]

Remove ads

Faculty

Summarize

Perspective

CUNY employs 6,700 full-time faculty members and over 10,000 adjunct faculty members.[88][89] Faculty and staff are represented by the Professional Staff Congress (PSC), a labor union and chapter of the American Federation of Teachers.[90]

Notable faculty

- André Aciman, writer, Graduate Center

- Ali Jimale Ahmed, poet and professor of Comparative Literature, Queens College and Graduate Center[91]

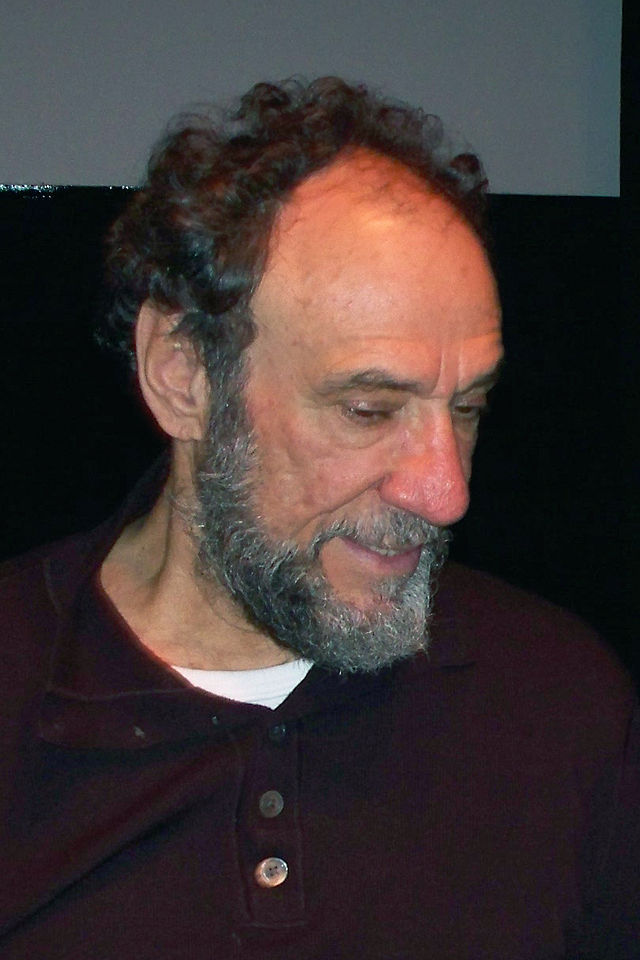

- F. Murray Abraham, actor of stage and screen; professor of theater, winner of the Academy Award for Best Actor, Brooklyn College

- Chantal Akerman, film director, City College of New York

- Meena Alexander, poet and writer, Graduate Center and Hunter College

- Hannah Arendt, philosopher and political theorist; author of The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) and The Human Condition (1958), Brooklyn College

- Talal Asad, anthropologist, Graduate Center

- John Ashbery, poet, Pulitzer Prize for Poetry winner, Brooklyn College

- William Bialek, biophysicist, Graduate Center

- Edwin G. Burrows, historian and writer, Pulitzer Prize for History winner for co-writing Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 with Mike Wallace, Brooklyn College

- Ron Carter, jazz bassist, City College

- Joe Chambers, jazz drummer, City College

- Dee L. Clayman, classicist, Graduate Center

- Margaret Clapp, scholar, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography, president of Wellesley College, Brooklyn College

- Ta-Nehisi Coates, writer, journalist, and activist, CUNY Graduate School of Journalism

- Billy Collins, poet, U.S. Poet Laureate, Lehman College (retired)

- Blanche Wiesen Cook, historian, John Jay College of Criminal Justice and Graduate Center

- John Corigliano, composer, Graduate Center

- Michael Cunningham, writer, winner of Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and PEN/Faulkner Award for The Hours, Brooklyn College

- Roy DeCarava, artist and photographer, Hunter College[92]

- Carolyn Eisele, mathematician, Hunter College

- Nancy Fraser, philosopher and political scientist, Graduate Center

- Ruth Wilson Gilmore, geographer, Graduate Center

- Allen Ginsberg, beat poet, Brooklyn College

- Aaron Goodelman, sculptor[93]

- Joel Glucksman, Olympic saber fencer, Brooklyn College

- Ralph Goldstein, Olympic épée fencer, Brooklyn College

- Michael Grossman, economist, Graduate Center

- Kimiko Hahn, poet, winner of PEN/Voelcker Award for Poetry, Queens College

- David Harvey, geographer, Graduate Center

- Jimmy Heath, jazz saxophonist, City College

- bell hooks, educator, writer and critic, City College of New York[94]

- Karen Brooks Hopkins, president of the Brooklyn Academy of Music, Brooklyn College

- John Hospers, first presidential candidate of the US Libertarian Party, Brooklyn College

- Tyehimba Jess, poet, winner of Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, College of Staten Island

- KC Johnson born (1967), Brooklyn College and Graduate Center

- Sheila Jordan, jazz vocalist, City College

- Michio Kaku, physicist, City College

- Jane Katz, Olympian swimmer, John Jay College of Criminal Justice

- Alfred Kazin, writer and critic, Hunter College and Graduate Center

- Saul Kripke, philosopher, Graduate Center

- Irving Kristol, journalist, City College

- Paul Krugman, economist, Graduate Center

- Peter Kwong, journalist, filmmaker, activist, Hunter College and Graduate Center

- Nathan H. Lents, scientist, author, and science communicator, John Jay College of Criminal Justice

- Ben Lerner, writer, MacArthur Fellow, Brooklyn College

- Audre Lorde, poet and activist, City College, John Jay College of Criminal Justice

- Cate Marvin, poet, Guggenheim Fellowship winner, College of Staten Island

- Abraham Maslow, psychologist in the school of humanistic psychology, best known for his theory of human motivation, which led to a therapeutic technique known as self-actualization, Brooklyn College

- John Matteson, historian and writer, Pulitzer Prize winner, John Jay College of Criminal Justice

- Maeve Kennedy McKean, attorney and public health official

- Stanley Milgram, social psychologist, Graduate Center

- Charles W. Mills, philosopher, Graduate Center

- June Nash, anthropologist, Graduate Center

- Ruth O'Brien, political scientist and disability studies writer, Graduate Center

- Denise O'Connor, Olympic foil fencer, Brooklyn College

- John Patitucci, jazz bassist, City College

- Itzhak Perlman, violinist, Brooklyn College[95]

- Frances Fox Piven, political scientist, activist, and educator, Graduate Center

- Roman Popadiuk, US Ambassador to Ukraine, Brooklyn College

- Graham Priest, philosopher, Graduate Center

- Inez Smith Reid, Senior Judge of the District of Columbia Court of Appeals, Brooklyn College

- Adrienne Rich, poet and activist, City College of New York[96]

- David M. Rosenthal, philosopher, Graduate Center

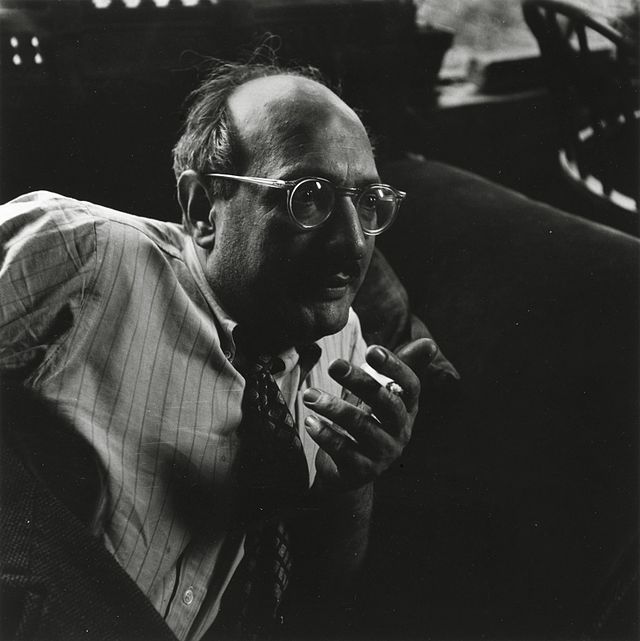

- Mark Rothko (born Markus Yakovlevich Rothkowitz), influential abstract expressionist painter, Brooklyn College

- Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., historian and social critic, Graduate Center

- Flora Rheta Schreiber, journalist, John Jay College of Criminal Justice

- Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, literary critic, Graduate Center

- Betty Shabazz, educator and activist, Medgar Evers College

- Mark Strand, United States Poet Laureate, Pulitzer Prize for Poetry-winning poet, essayist, and translator, Brooklyn College

- Dennis Sullivan, mathematician, Graduate Center

- Harold Syrett (1913–1984), president of Brooklyn College

- Katherine Verdery, anthropologist, Graduate Center

- Michele Wallace, women's studies and film studies, City College and Graduate Center

- Mike Wallace, historian and writer, John Jay College of Criminal Justice and Graduate Center

- Ruth Westheimer (better known as Dr. Ruth; born Karola Ruth Siegel), sex therapist, media personality, author, radio, television talk show host, and Holocaust survivor, Brooklyn College

- Elie Wiesel, novelist, political activist, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, Presidential Medal of Freedom, and Congressional Gold Medal, City College

- C. K. Williams, poet, won Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, Brooklyn College

- Andrea Alu, engineer and physicist, Graduate Center

- Robert Alfano, physicist, discovered the supercontinuum, City College

- Branko Milanović, economist most known for his work on income distribution and inequality; a visiting presidential professor at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, an affiliated senior scholar at the Luxembourg Income Study and former lead economist in the World Bank's research department.

- Simi Linton, arts consultant, author, filmmaker, and activist. Focuses on disability in the arts, disability studies, and ways that disability rights and disability justice perspectives can be brought to bear on the arts.

Remove ads

Public Safety Department

Summarize

Perspective

CUNY has a unified public safety department, the City University of New York Public Safety Department, with branches at each of the 26 CUNY campuses.[97] The New York City Police Department is the primary policing and investigation agency within the New York City as per the NYC Charter, which includes all CUNY campuses and facilities.

The Public Safety Department came under heavy criticism from student groups, after several students protesting tuition increases tried to occupy the lobby of the Baruch College. The occupiers were forcibly removed from the area and several were arrested on November 21, 2011.[98]

Antisemitism at CUNY

In recent years, there have been a number of antisemitic incidents on CUNY campuses, including:

- In March 2014, Brooklyn College settled the Title VI complaint that the Zionist Organization of America ("ZOA") had filed against its antisemitic discrimination.[99]

- In 2017, a CUNY admin was recorded saying that there were too many Jews on campus.[100]

- In 2020, a CUNY student was arrested for spray-painting antisemitic graffiti on a campus building. [citation needed]

- In 2021, a survey found that nearly one in four CUNY students had experienced antisemitism on campus. The survey also found that Jewish students were more likely to report feeling unsafe on campus than students of other faiths.[101]

- In May 2021, a student at John Jay posted a picture of Adolf Hitler on Instagram with a message saying "We need another Hitler today." A group of Jewish students met with Karol Mason, the President of the college, who refused to condemn the action publicly.[99]

- The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission cited CUNY in 2021 for failing to protect a Jewish professor after the PSC discriminated against him and subjected him to a hostile work environment on the basis of his Jewish faith.[102]

CUNY has taken steps to address antisemitism on its campuses. In 2020, the university created a task force to combat antisemitism. The task force has developed a number of initiatives, including training for faculty and staff on how to identify and address antisemitism.[103]

In June 2024, the United States Department of Education concluded that CUNY has failed to protect Jewish students from discrimination following the October 7 attacks. CUNY's Hunter College also faced scrutiny for incidents dating back to 2021. In response, Chancellor Félix V. Matos Rodríguez stated that CUNY is dedicated to maintaining a discrimination-free and hate-free environment, and that new measures will ensure consistent and transparent investigation and resolution of complaints.[104]

Remove ads

City University Television (CUNY TV)

CUNY also has a broadcast TV service, CUNY TV (channel 75 on Spectrum, digital HD broadcast channel 25.3), which airs telecourses, classic and foreign films, magazine shows, and panel discussions in foreign languages.

City University Film Festival (CUNYFF)

The City University Film Festival is CUNY's official film festival. The festival was founded in 2009.[105][106]

Notable alumni

Summarize

Perspective

CUNY graduates include 13 Nobel laureates, 2 Fields Medalists, 2 U.S. Secretaries of State, a Supreme Court Justice, several New York City mayors, members of Congress, state legislators, scientists, artists, and Olympians.[80][107]

Remove ads

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads