Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Critical rationalism

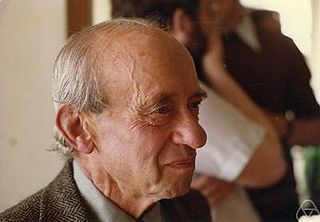

Epistemological philosophy advanced by Karl Popper From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Critical Rationalism is Karl Popper's answer to what he considered the most important problems of epistemology and philosophy of science: the problems of the growth of knowledge, notably by induction, and the demarcation of science. He adopted a fallibilist approach to these problems, especially that of induction, without falling into skepticism. His approach was to put in perspective the distinctive role of deductive logic in the development of knowledge, especially in science, in the context of a less rigorous methodology based on critical thinking. The central technical concept in the application of critical rationalism to science is falsifiabiity. Popper first mentioned the term "critical rationalism" in The Open Society and Its Enemies (1945),[1] and also later in Conjectures and Refutations (1963),[2] Unended Quest (1976),[3] and The Myth of the Framework (1994).[4]

Remove ads

Fallibilism, not skepticism

Summarize

Perspective

Popper admitted that the truth of statements cannot be obtained using only logical definitions and deductions, as this leads to an infinite regress.[5] For Popper, this does not prevent statements from being useful for solving problems, because they can be logically analyzed to draw logical consequences, possibly contradictions with observation statements linked to real tests.[5] Popper wrote that the bulk of scientific activities use deductive logic to evaluate theories.[6][7][8]

Popper accepted Hume's argument and the consequences of Duhem's thesis and insisted that there is no logical method for accessing empirical truth, no inductive rule, not even to a small extent. However, he rejected skepticism, the idea that the search for truth is futile. He admitted that, although logic alone says nothing about empirical truth, statements can be related to reality through problem solving, scientific observations and experiments.[9] Popper always insisted on this distinction between the logical aspect and methodological aspect of science.[10][11] In Realism and the Aim of Science, Popper speaks of a "preferred" theory, not of a "true" or a "false" theory, when one theory is chosen over another given experimental results.[9]

Remove ads

Tarski's semantic theory of truth

Summarize

Perspective

Popper was always aware that empirical truth eludes logic alone, and he was therefore reluctant to refer to the truth of scientific theories. This, he wrote, changed after reading Tarski's semantic theory of truth. He saw this theory as a way of talking about truth as a correspondence with facts. A key aspect of Tarski's theory, which Popper considered important, is the separation between the logical (formal) aspect of language as an object and its semantic interpretation. He saw this as a way of explaining the distinction between the logic of science and its methodology, or rather between logic and the metaphysical component to which methodology refers when it aims, for example, to test theories. The difference is that in Tarski's theory, "facts" are mathematical structures, not an external reality beyond the reach of logic and its language, and which we can only describe artificially in a meta-language as in the argument "Snow is white" (in the object language) is true because snow is white (in the meta-language). This use of Tarski's theory is accepted by some and sharply criticized by others. Popper used it, for example, in Realism and the Aim of Science, to explain the difference between the metaphysical versions of the problem of induction and its logical versions. He wrote that the metaphysical versions of the problem refer to the "meta-theory of physics" and compared this to what Tarski calls the "semantics" in its theory of truth.[12]

Remove ads

The role of methodology

Summarize

Perspective

For Popper, the bulk of activities in science use deductive logic on statements,[6][7][8] but this logical part of science must be integrated within an adequate methodology.[13] The logical part is considered incapable of justifying empirical knowledge on its own. For example, Popper and the members of the Vienna Circle agreed that only statements can be used to justify statements, that is, the use of logic alone in science will not be linked to (empirical, not propositional) evidence.[14][15] Logic uses accepted or provisionally accepted observation statements to determine whether a theory is logically refuted or not, but the "accepted" observation statement could be empirically false and that will not concern the logical part.[11]

Popper wrote that the bulk of scientific activity takes place in the logical part, using deductive logic to check the consistency of a theory, compare theories, check their empirical nature (i.e., falsifiability) and, most importantly, test a theory, which is possible only when it is falsifiable. He emphasized that, even when theories are tested against observations, deductive logic is largely used.[6][8] Despite this intensive use of logic, Popper accepted, as do most philosophers and scientists, that logic alone does not connect by itself with evidence. Popper explained this dilemma by stating the existence of a natural separation (not a disconnection) between the logical and the methodological parts of science.[10][11]

Popper wrote that any criterion, including his famous falsifiability criterion, that applies solely on the logical structure could not alone define science. In The Logic of Scientific Discovery, he wrote "it is impossible to decide, by analysing its logical form [as do the falsifiability criterion], whether a system of statements is a conventional system of irrefutable implicit definitions, or whether it is a system which is empirical in my sense; that is, a refutable system."[16][17] Popper insisted that falsifiability is a logical criterion, which must be understood in the context of a proper methodology.[10][11] The methodology can hardly be made precise.[18] It is a set of informal implicit conventions that guide all the decisions that surround the logical work, which experiments to conduct, which apparatus to build, which domain will be financially supported, etc., aspects that were raised by Lakatos in The Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes.[19]

Popper's philosophy was criticized as if the logical part existed alone. For example, Putnam attributed to Popper "the fantasy of doing science using only deductive logic".[20] Putnam further criticized Popper's description of the logical part of science by referring to methodological problems. For example, he wrote "I claim: in a great many important cases, scientific theories do not imply predictions at all."[21] Because Popper does not believe in inductive logic, Wesley Salmon wrote that, for Popper, "there is no ampliative form of scientific argument, and consequently, science provides no information whatever about the future".[22] Regarding the methodological part, Feyerabend wrote that there is no method in science. He considered and rejected methodological rules, but they were those of a naive falsificationist.[23]

In contrast, Popper emphasized both parts of science and spoke of methodology as a means of correctly using falsifiability and the usual logical work in science to make it useful in a method of conjectures and refutations to be used in usual critical discussions. Falsififiability says hypotheses should be consistent and they should logically lead to predictions, which confrontation with observations should be considered in critical thinking.[7]

Remove ads

Marxism and politic

Summarize

Perspective

The failure of democratic parties to prevent fascism from taking over Austrian politics in the 1920s and 1930s traumatised Popper. He suffered from the direct consequences of this failure. Events after the Anschluss (the annexation of Austria by the German Reich in 1938) prompted him to refocus his writings on social and political philosophy. His most important works in the field of social science—The Poverty of Historicism (1944) and The Open Society and Its Enemies (1945)—were inspired by his reflection on the events of his time and represented, in a sense, a reaction to the prevalent totalitarian ideologies that then dominated Central European politics. His books defended democratic liberalism as a social and political philosophy. They also represented extensive critiques of the philosophical presuppositions underpinning all forms of totalitarianism.[24]

Earlier in his life, the death of friends in a demonstration instigated by the communists when he was about seventeen strongly contributed to Popper's position regarding the search for contradictions or criticisms and the attitude of taking them into account. He had at one point joined a socialist association, and for a few months in 1919 considered himself a communist.[25] Although it is known that Popper worked as an office boy at the communist headquarters, whether or not he ever became a member of the Communist Party is unclear.[26] During this time he became familiar with the Marxist view of economics, class conflict, and history.[24] He blamed Marxism, which thesis, Popper recalls, "is that although the revolution may claim some victims, capitalism is claiming more victims than the whole socialist revolution". He asked himself "whether such a calculation could ever be supported by 'science'." He then decided that criticism was important in science.[27] This, Popper wrote, made him "a fallibilist", and impressed on him "the value of intellectual modesty". It made him "most conscious of the differences between dogmatic and critical thinking".[28]

Remove ads

Psychoanalysis

Summarize

Perspective

Popper saw a contrast between the theories of Sigmund Freud and Alfred Adler, which he considered unscientific, and Albert Einstein's theory of relativity which sparked the revolution in physics in the early 20th century. Popper believed that Einstein's theory, as a theory properly grounded in scientific thought and method, was highly "risky", in the sense that it was possible to deduce consequences from it that differed considerably from those of the then-dominant Newtonian physics.[29] One such prediction, that gravity could deflect light, was verified by Eddington's experiments in 1919.[30] When he tackled the problem of demarcation in the philosophy of science, he realized that "what made a theory, or a statement, scientific was its power to rule out, or exclude, the occurrence of some possible events—to prohibit, or forbid, the occurrence of these events."[31] He thought that, in contrast, nothing could, even in principle, falsify psychoanalytic theories. This led him to posit that "only attempted refutations which did not succeed qua refutations should count as 'verifications'."[32]

A little later, Popper realized that theories can be "immunized" against falsification using auxiliary hypotheses. In Logik der Forschung, he introduced the notion of "(degrees of) content". He proposed that only modifications that increase the empirical content of a theory should be considered.[33]

In a series of articles beginning in 1979, Adolf Grünbaum argued, with examples, that Freudian psychoanalytic theories are in fact falsifiable. He criticized Popper's analysis of Freud's psychoanalytic theories and, on this basis, questioned the applicability of the demarcation criterion in general.[34]

Remove ads

Falsifiability, probability statement and metaphysics

Summarize

Perspective

Popper identified scientific statements with falsifiable statements and distinguished them from metaphysical statements. But, he considered metaphysical statements useful in science. In particular, probabilistic statements are non falsifiable and thus metaphysical in Popper's terminology.[35] There are many other kinds of metaphysical statements that are useful in Popper's view. For examples, "all men are mortal" is metaphysical, because it is not falsifiable, but such statements suggest other hypotheses that are more precise and more useful, for example "all men die before reaching the age of 150."[36] Similarly, probabilistic hypotheses suggest other hypotheses that are falsifiable such as the acceptance criteria for the null hypothesis in a statistical test.[37] As another example: a statistical hypothesis like a Chi-Square test is not a universal statement; it concerns a specific study, but is falsifiable and thus useful in critical discussions. A probability statement like "the probability of both heads and tails are 1/2" is not falsifiable; Popper called this problem of strengthening probability statements to make them falsifiable (i.e. incompatible with some sequences) and thus not metaphysical "the problem of decidability of probability statements." [38]

Remove ads

Critical thinking, not support

Summarize

Perspective

Popper distinguished between trusting a theory because it is true and preferring a theory because it has been more severely tested.[39] Some have argued that, indirectly, Popper was adopting an inductive principle when he proposed to "prefer" a more severely tested theory.[40][41][42] For Popper, the term "induction" refers to a logical method of justification, and he emphasized that this preference does not result from such a logical process whose premises would be the results of rigorous tests. For Popper, results of rigorous tests are rather used in critical discussions. He wrote:[39]

[T]here is no 'absolute reliance'; but since we have to choose, it will be 'rational' to choose the best-tested theory. This will be 'rational' in the most obvious sense of the word known to me: the best-tested theory is the one which, in the light of our critical discussion, appears to be the best so far, and I do not know of anything more 'rational' than a well-conducted critical discussion.

— Karl Popper, Logik der Forschung (1934)

Moreover, critical discussions must consider how much the theory prohibits and thus is unlikely to survive the tests, as well as whether the theory supersedes previous theories by generalizing them as when speaking of all heavenly bodies instead of only planets.[43][44] Popper regularly emphasized that criticism in critical discussions requires the use of background knowledge, but rejected the view there will always be a set of assumptions beyond rational assessment.[45] In particular, Popper brought this point in the context of the empirical basis of science, which he compared to a swamp into which it is always possible to drive pillars deeper if a more solid foundation is needed.[46]

The critical rationalism approach to evaluating scientific theories can be generalized to non-scientific domains.[47] Critical rationalists hold that any claims to knowledge can and should be rationally criticized, and, if they have empirical content, can and should be subjected to tests which may falsify them. They are either falsifiable and thus empirical (in a very broad sense), or not falsifiable and thus non-empirical. The general principle of critical rationalism is the same in both cases: we critically analyze the hypotheses using our "background knowledge".[48] In the case of scientific hypotheses, background knowledge is used while observation statements are discussed or analysed.[48]

Remove ads

Bayésianisme vs conjecture and refutation

Summarize

Perspective

Use of probability in a verificationist approach, "similar in some ways to that of modern pragmatists and positivists", has been traced back to Carneades.[49] In the first half of the 20th century, Reichenbach and Carnap argued that "the only criterion of theory-confirmation ought to be agreement with observed facts; the theory would thus be the 'most probable' one ... within a formal theory of inductive probability."[50] Carnap studies have been related to Bayesianism.[51][52] Theories are assigned a probability, outcomes also have a probability and, given an outcome, Bayes' theorem can be applied to revise the a priori probability of each theory.[53] Bayes' theorem is useful when we have the background knowledge needed to establish the a priori probability of characteristic parameters of the application domain and the probability of the observed data depends on these parameters: the parameters that fit the data and therefore the domain get revised with a higher probability.[54]

This view on the growth of knowledge has been criticized. Andrew Gelman and Cosma Shalizi, for example, wrote that the use of Bayes's theorem in practice is closer to the hypothetico-deductive approach, as proposed by Popper and others, than to the approach according to which the revision of probabilities is the sole consequence of the observed data.. In their work, they "examine the actual role played by prior distributions in Bayesian models, and the crucial aspects of model checking and model revision, which fall outside the scope of Bayesian confirmation theory.[55]

Critical rationalism is against the use of probability to assess theories. Popper explained that the greater the informative content of a theory the lower will be its probability.[56][57] He wrote that in "many cases, the more improbable (improbable in the sense of the calculus of probability) hypothesis is preferable.[57] He also wrote that "it happen quite often that I cannot prefer the logically 'better' and more improbable hypothesis, because somebody succeeded in refuting it experimentally."[58]

Remove ads

Justified true belief versus objective knowledge

Summarize

Perspective

In mainstream epistemology, there are different types of knowledge, such as knowing someone or knowing how to drive, each associated with a type of mental and biological phenomenon. Knowledge defined as justified true belief is also a particular type of mental phenomenon. In this case, at the very least, the phenomenon is a belief in a fact identified by a proposition. The proposition in question must also be true, because it is absurd to say that we possess knowledge of something false. The proposition must also be justified.[59]

Defining knowledge as a justified true belief is rarely a foundation accepted without discussion. On the contrary, it often constitutes a starting point for critical analysis based on counterexamples such as those presented by Gettier. For example, Meinong, at the beginning of the 20th century, cites the example of a man disturbed by ringing in his ears coming from his head. He infers that someone is ringing his doorbell when, by chance, someone is. His belief is true and justified by sensory perception, but, in a critical analysis of knowledge, he was simply lucky and doesn't really know that someone is ringing his doorbell.[60] Long before this, similar counterexamples were raised in the Indian tradition and in ancient Greece.[61][62]

These historical examples suggest that this view of knowledge has always been studied and criticized throughout the long history of philosophy. However, it was only in the mid-20th century that the analysis of knowledge as a justified mental attitude toward a true proposition emerged as a major subject of study in epistemology. According to Sander Verhaegh, prior to this period, Russell, Moore, and others had briefly analyzed knowledge as a justified true belief, but only to reject this project.[63]

In contrast to this emphasis on justifying beliefs, Popper advanced the method of conjectures and refutations, in which beliefs can play a role in choosing a hypothesis or conjecture, but do not interfere with the use of deductive logic to test theories.[64] Popper did not reject the role of beliefs and other subjective aspects in the development of knowledge, but in his methodology, the logical component is deductive and applies directly to conjectures and observational statements, free from psychologism.[65]

This did not prevent authors such as Bredo Johnsen and Paul Tibbetts from criticizing Popper as if he had claimed that logic and methodology were sufficient to explain the development of knowledge. Johnsen points out that Popper explains that the method of error elimination using logical refutations requires that a finite number of theories be studied. He argues that Popper does not explain how one arrives at this finite number of theories.[66] Tibbetts raises the question of "whether Popper’s position can take into account creative insight, discovery, and serendipity in science for these would clearly qualify as subjective phenomena [in Popper's position]."[67]

On this subject, Popper admitted that objective knowledge develops through the individual contributions of researchers and that this depends on their biological predisposition to produce new, working theories: for Popper, “objectivity depended not on neutralizing the scientist’s subjective dispositions – which was, in any case, impossible – but on subjecting all theories to severe testing.”[68] Popper accepted Hume’s conclusion that it is futile to attempt to provide a method to guide or validate the process of discovery. He used the terms “expectations” and “dispositions” to explain the development of knowledge and our mental capacities.

According to Suzan Haack, to support his approach, Popper has to make a problematic distinction between logic and empirical theories.

For her part, Susan Haack criticizes the separation that Popper seems to make between the rules of logic and the mathematical statements forming the empirical laws or axioms of its structures. Regarding the autonomy that Popper attributes to the world of objective knowledge, she writes:[69]

Is not the point just this: that just as the nests, etc., that animals create are subject to natural laws which are not of the animals' creation, so the theories, etc., that we create are subject to logical laws which are not of our making? If this is the point, I think it needs to be said that it is more surprising than it perhaps looks. For it requires Popper to draw a sharp line between empirical science and mathematics, which he explicitly says that we have created, and logic, which, on this interpretation, he must hold to be entirely independent of us.

— Susan Haack, Epistemology with a Knowing Subject, 1979

On this subject, Popper defended an evolutionary view of the whole of human capacities, including our ability to use language and logic in its function of argumentation, but he also specified that this biological aspect did not fall within the field of epistemology.[70][67]

He accepted that the choice of methodological rules must take into account subjective, moral, or biological aspects such as the limits of human mental capacities,[71] but he compared the rules of scientific methodology to the rules of chess, which can be understood without having to worry about any subjective aspects, apart from the capacity for rational thought and other similar functions. He gave examples that methodology can take into account regarding the activity of a scientist S in relation to a proposition p:

- 'S tries to understand p.'

- 'S tries to think of alternatives to p. '

- 'S tries to think of criticisms of p.'

- 'S proposes an experimental test for p.'

- 'S tries to axiomatize p.'

- 'S tries to derive p from q.'

He added that this is very different from the use of "S knows p" or "S believes p", or even "S wrongly believes p" or "S doubts p" in an analysis of knowledge and its justification.[72]

For Popper, this separation between logic, methodology, and psychological aspects was the concrete reality in science; that is, his methodology, which is normative, is simultaneously descriptive of what he considered to be true scientific activity. He emphasized that a large part of science relies on standard deductive reasoning, even when it comes to comparison with observations. David Miller noted that, for Popper, knowledge is neither justified nor believed, and that, generally, scientific knowledge is not true (in any logical sense).[73][74] Musgrave wrote that "Popper's theory of science, and his cure for relativism, rest upon his rejection of the traditional theory of knowledge as justified true belief."[75]

Remove ads

Variations

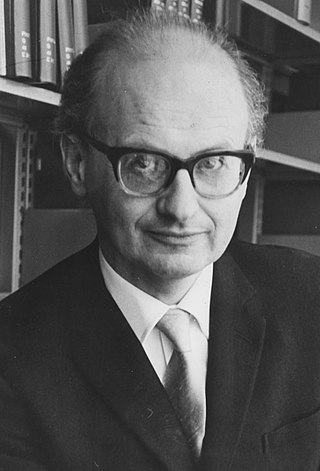

William Warren Bartley developed a variation of critical rationalism that he called pancritical rationalism.[76][77][78]

The Argentine-Canadian philosopher of science Mario Bunge criticized Popper's critical rationalism,[79][80] while drawing on it to formulate an account of scientific realism.[81][82][83]

See also

People

Citations

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads