Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Cyprus–Greece relations

Bilateral relations From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

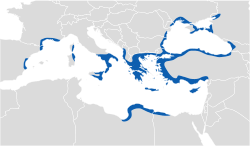

Cyprus–Greece relations are the bilateral and historic relations between the Republic of Cyprus and the Hellenic Republic. Cyprus has an embassy in Athens and a consulate-general in Thessaloniki. Greece has an embassy in Nicosia. Both countries are full members of the United Nations, European Union, Council of Europe and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). Relations between the two countries have been exceptionally close since the Republic of Cyprus was formed in 1960. The Greek populations in Cyprus and Greece share a common ethnicity, heritage, language, and religion. Greece has given full support to Cyprus' membership in the European Union.

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

Early relations

As early as the 2nd millennium BC, Mycenaean-Achaean Greeks settled permanently in Cyprus and brought their language and culture to the island. This made Cyprus part of the ancient Greek world and, despite later foreign rule, it retained a predominantly Greek identity. According to Greek mythology, the island was the birthplace of Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love. After its conquest by Alexander the Great (333 BC), Cyprus belonged to the Hellenistic Empire of the Ptolemaic dynasty and subsequently came under Roman control. In late antiquity, Cyprus became part of the Eastern Roman Empire, which further strengthened its ties to the Greek language and Orthodox Christianity. Although the island was temporarily exposed to Arab incursions during the Byzantine period and later (1192–1571) came under the rule of the Frankish Lusignan dynasty and the Republic of Venice,[1] the Greek Cypriot population remained culturally and linguistically dominant. Until its conquest by the Ottoman Empire in 1571, Cyprus had thus established itself as an integral part of the Greek cultural sphere.

Ottoman period

Cyprus remained under Ottoman rule from 1571 to 1878. The Ottoman administration allowed the Orthodox archbishop to remain as ethnarch of the Greek Cypriot community, thereby preserving the language, religion, and Greek customs of the majority population.[2] During the Greek War of Independence in 1821, tensions also arose in Cyprus: the Ottoman authorities suspected the local Greek population of supporting the revolution and, on July 9, 1821, executed Archbishop Kyprianos and almost 500 other prominent Greek Cypriots.[3] Despite such repression, the Greek Cypriot population remained committed to their Greek orientation. After Greece gained independence in 1830, the desire among Cypriots to join the Greek state (Enosis) grew. In the 19th century, ideas from the Greek national movement and memories of the oppression experienced during the Ottoman era fueled this aspiration. Ottoman rule finally ended as a result of geopolitical agreements: in 1878, Cyprus was handed over to the British Empire for administration under the Cyprus Convention. The British annexed the island in 1914 after the start of World War I. In the first British census in 1881, approximately three quarters of the population of Cyprus were Greek Cypriots, while Turkish Cypriots accounted for just under 24 percent.[2]

British colonial period and independence of Cyprus

Under British colonial rule (1878–1960), Greek Cypriots increasingly articulated their desire for unification with Greece.[4] When the British arrived in 1878, many Cypriots hoped that Great Britain would sooner or later cede the island, following the example of the transfer of the Ionian Islands to Greece (1864). The Orthodox Church and secular representatives submitted memoranda and sent delegations to London, but the colonial power rejected such demands because of the island's strategic importance. The British made a historic offer during World War I: in 1915, London offered Cyprus to the Greek government in return for its entry into the war on the side of the Entente, but the neutral government in Athens (under Prime Minister Alexandros Zaimis) rejected the offer.[2]

After the World War II, the conflict over Cyprus escalated. From 1954 onwards, Greece brought the Cyprus question before the United Nations and insisted on the Cypriots' right to self-determination.[5] At the same time, the underground organization EOKA was formed on the island under the leadership of officer Georgios Grivas and with the support of Archbishop Makarios III, which led an armed uprising against the colonial power from 1955 onwards. EOKA fought for an end to British rule and ultimately sought union with Greece.[6] The guerrilla war lasted until 1959 and forced all parties involved to back down from their maximum demands. In February 1959, Great Britain, Greece, and Turkey agreed in the Zurich and London Agreements on the independence of Cyprus in the form of a bi-communal republic. Greece and Turkey assumed the role of guarantor powers, contractually agreeing to uphold Cyprus's independence and securing their influence through the right to station a contingent of their own troops on Cyprus and to intervene on the island if necessary.[7]

The Republic of Cyprus was officially founded on August 16, 1960. However, the first years of independence were marked by intercommunal tensions and violence between the Greek and Turkish Cypriot populations. Greece supported the young republic politically and also sent military advisers under the terms of the alliance treaty. From 1967 onwards, the Greek military junta ruling in Athens exerted growing influence in Cyprus and promoted pro-Greek hardliners. In July 1974, the Greek junta supported a coup by the Cypriot National Guard as part of efforts to achieve unification between Greece and Cyprus. This was followed shortly thereafter by the Turkish invasion of Cyprus, resulting in the current division of the island. Around 37% of the country's territory came under the control of the Turkish armed forces, triggering a massive wave of expulsion of Greek Cypriots from the north, who were replaced by Turkish settlers.[8]

Relations after 1974

After the fall of the military dictatorship in 1974, Greece returned to democracy and pursued a consistently supportive stance toward the Republic of Cyprus on the Cyprus issue. Athens condemned the Turkish occupation of northern Cyprus and demanded respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Republic in all international forums.[8] In the decades that followed, Greece and Cyprus developed close cooperation on security policy. In 1993, both governments adopted a joint defense doctrine that incorporated Cyprus into the Greek defense zone and stipulated that any Turkish attack on Cyprus would be considered a casus belli for Greece.[9] At the same time, the countries intensified their diplomatic coordination: Greece strongly supported Cyprus in its efforts to move closer to the European Communities. In the 1990s, Athens even threatened to veto the EU's eastward enlargement if Cyprus was not included in the first round of accession. This stance contributed to the EU's assurance in 1999 that it would not consider the unresolved Cyprus conflict as an obstacle to accession. As a result, the Republic of Cyprus – with Greek backing – became a member of the EU in 2004.[10]

Since then, Greece and Cyprus have been closely coordinating their foreign and European policies. Both countries firmly reject the two-state solution for Cyprus propagated by Turkey since 2020 and insist on the established framework of a bizonal, bicommunal federation in accordance with UN resolutions. Athens and Nicosia are also jointly calling for the withdrawal of Turkish troops and the abolition of the outdated system of guarantor powers as part of a solution. In 2021, Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis and the Cypriot leadership reaffirmed that only reunification in the form of a federal republic with political equality for both communities is acceptable.[11] Beyond the Cyprus issue, Greece and Cyprus are stepping up cooperation with like-minded neighbors in the eastern Mediterranean. Since 2014, they have been establishing trilateral alliances with countries such as Israel and Egypt to promote regional stability, energy cooperation (e.g., in the East Mediterranean Gas Forum), and security.[4]

Remove ads

Economic relations

Traditionally, Greece has been the major export and import partner of Cyprus. In 2019, Greece produced $257,165.64 US Dollars in exports $1,855,624.30 US Dollars in imports for Cyprus, being Cyprus's first ranking import partner.[12] Both countries benefit from the common European single market and the introduction of the euro (Greece in 2001, Cyprus in 2008), which has facilitated trade and investment. Greek companies are heavily involved in the Cypriot market, for example in the banking sector, construction, and tourism. At the same time, Cypriot companies—mainly from the financial and shipping sectors—invest in Greece. The close ties between the two countries became apparent during the Greek sovereign debt crisis: the haircut on Greek government bonds in 2012 hit Cypriot banks hard and led to write-offs of over €4 billion (around 60% of their equity), which was one of the factors that triggered the banking crisis in Cyprus in 2013.[13]

Remove ads

Cultural relations

Summarize

Perspective

The cultural ties between Greece and Cyprus are extremely close, as the population of Cyprus (around 78% Greek Cypriot) belongs ethnically, linguistically, and religiously to the Greek cultural sphere. Greek is the official language of the Republic of Cyprus, and the vast majority of Cypriots belong to the Greek Orthodox Church, as do the Greeks. Shared traditions and holidays underscore this bond: Greek Independence Day (March 25) is an official holiday in Cyprus, when schools, government offices, and many businesses are closed.[14] Greek media (television, music, literature) are an integral part of everyday life in Cyprus, and numerous Cypriot artists and students work in Greece. In general, there is an intensive educational exchange: of the approximately 21,000 Cypriot students abroad in 2008/09, almost 60% were enrolled at universities in Greece.[15]

Family ties across the Aegean Sea are also common, as many Cypriots married, studied, or settled permanently in Greece during the 20th century. However, migration flows in both directions: immediately after the division of the island in 1974, several thousand Greek Cypriots found refuge in Greece, while more recently Greek workers have also moved to Cyprus in search of better job prospects. The cultural similarities are also reflected in the education system—Greece has always been a role model for the Cypriot education system, and Cypriot textbooks, curricula, and university degrees are closely based on Greek standards.[16]

Similarity of Anthems

Greece and Cyprus have the same anthem. Greece adopted the anthem in 1865, while Cyprus adopted it in 1966.[citation needed]

European Union

NATO

While Greece became a member of NATO in 1952, Cyprus has never been a member of NATO.

Resident diplomatic missions

- Cyprus has an embassy in Athens and a consulate-general in Thessaloniki.

- Greece has an embassy in Nicosia.

- Embassy of Greece in Nicosia

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads