Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Doikayt

Political concept emphasizing the right of Jews to live and organize wherever they are From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Doikayt (Yiddish: דאָיִקייט, lit. 'Hereness') is a principle which states that Jews have a right to live and organize wherever they reside, and that they should focus on the challenges facing their local communities.

Also transliterated as Do'ikayt, Doikait, Doikeyt, Doykait, Doykayt, and Doykeit, the word is a combination of the Yiddish word דאָ (romanized: do, lit. 'here'), an adjectival suffix יק (-ik), and a noun suffix -קייט (kayt, similar to '-ness'), doikayt is often posed as an opposition to dortkayt (דאָרטקייט, lit. 'thereness'), as represented by migration and the Zionist movement.[1]

The Jewish English Lexicon defines doikayt as "Diasporism; an ideology that discourages Jewish nationhood, advocating instead for Jewish communities to remain dispersed and politically engaged within their host countries."[2] Others have defined it as "the political desire to solve the questions and problems of the Jews in the place where they lived, as opposed to solutions which implied migration"[3] and as the idea that "Jews had the right to live in freedom and dignity wherever it was they stood [...] fight for freedom and safety in the places where they lived, in defiance of everyone who wanted them dead".[4] As such, the concept has been likened to the Palestinian concept of Sumud.[4] Others have defined it as "a catch-all term in Eastern European Jewish historiography for the commitment of various early 20th century non-Zionist political movements to the diaspora".[5] Another view defines doikayt as consisting of two tenets: organizing where Jews live for the improvement of their lives, and promoting Jews' sense of history, culture, and belonging to the places where they live.[6]

For some, the concept is closely linked with Non-Zionism, Anti-Zionism,[7][4] and solidarity with Palestine.[8] Other groups have cited doikayt in their choice to avoid taking a stance on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and focusing on local issues instead.[8] Bundists in Israel used doykait to explain their attachment to Israel,[5] as well as to explain their non-Zionist stance, stating: "I view Israel as something that is there, an important thing. I am here, in my country, but I don't call myself a Zionist [...] far from it."[9]

Molly Crabapple links doikayt to Anti-Zionism, contrasting the Bund's "insistence on staying: Doikayt (hereness)" to the Zionist "'there' of Palestine".[10] However, Rokhl Kafrissen argues that "Though the Bund was strongly against the establishment of a Jewish state in Israel, the original context of doikayt wasn't merely, or even mostly, a negation of Zionism", but rather a reaction to the great Jewish emigration out of Eastern Europe. She continued: "The Bundist movement argued that Jews could, and should, stay in Eastern Europe and build a new, more just society."[11]

Remove ads

Origins of the term

Summarize

Perspective

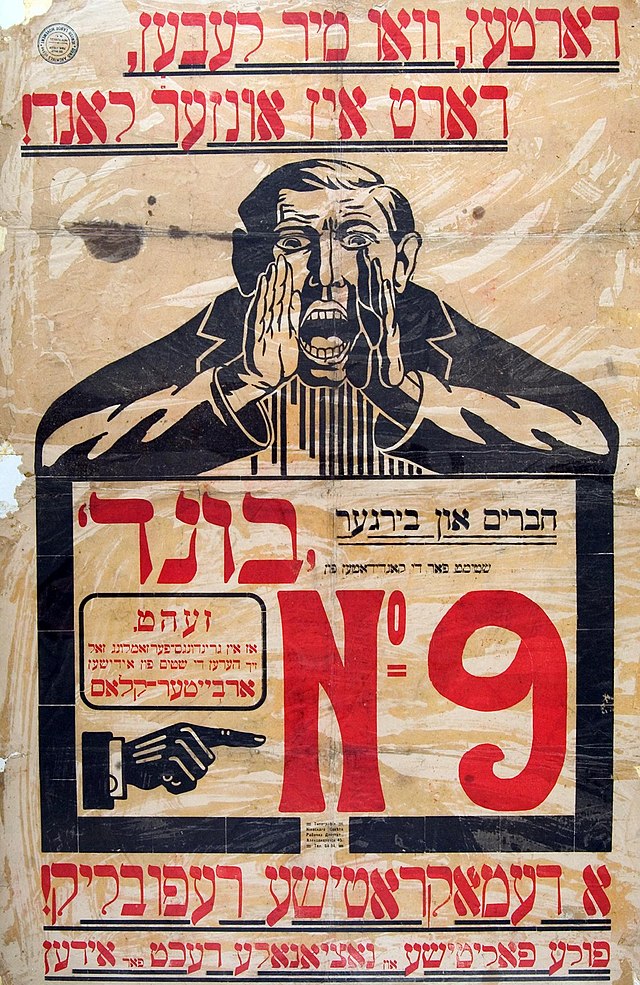

The term doikayt is often associated with Bundism and the Bund, especially in Poland during the inter-war period.[5][6] Some examples emphasize the roles of Vladimir Medem[12] and Henryk Ehrlich[13] in this context. The Bund's commitment to doikayt is demonstrated by slogans such as "Here where we live is our country" and a belief in the rights of Jews "to live in freedom and dignity wherever it was they stood".[4] Contemporary descriptions of doikayt also emphasize its links to Bundism and the Bund.[14][15][8] However, there aren't any known recorded uses of the term in the context of the Bund in interwar Poland.[16] It has been argued that during the Interwar period, the Bund's focus was on class struggle and other Socialist themes, whereas the debate with Zionists emphasizing doikayt only became central after World War II and The Holocaust.[5] Thus, while it is clear that the idea of doikayt was present in Polish Bundist circles during the interwar period, the term itself was only attributed to them in retrospect.[5][6] One of the earliest known use of the term in the context of Bundism is in Leyvick Hodes' "Mitn ponem tsu der tsukunft" (Facing the Future) from 1947.[17][16]: 6–7 From this moment on, the term appears frequently in Bundist writing.[5]

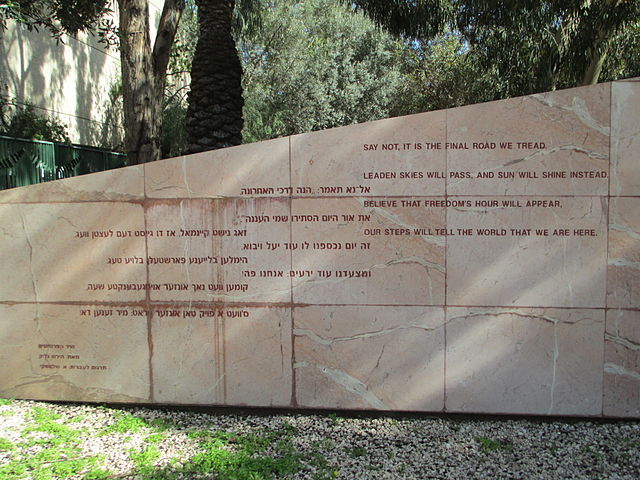

A more likely origin of the term doikayt is in interwar Lithuania, specifically in the context of the Folkspartei and its debates with the Zionist movement. The Folkspartei opposed emigration as advised by Zionism and instead called to "remain here (bleibn do)".[18] The term was used in an article by Yudl Mark (1897–1975) in 1926 where it was defined as "principled diasporism".[5] Mark and other members of the Folkspartei such as Nochum Shtif juxtaposed the diasporic "here" with the Zionist "there" in their writing since as early as 1910.[5] Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the term appeared in debates between Folkists and Zionists in Lithuanian Jewish newspapers.[5] In 1936, reflecting on Uriah Katzenelenbogen's journal Lite, Mark wrote in "Yidishe periodishe oysgabes in Lite"[19] that the journal's purpose was "to instill in Jews themselves more connectedness to Lithuania and call for a principle standpoint of doikayt as a response to the Zionist dortikayt."[5] Another example of adherence to doikayt by Jews in Lithuania may be found in Hirsh Glick's Zog nit keyn mol (Partizaner lid or "Partisan song"), written in Vilnius in 1943, which includes the refrain "mir zaynen do!" ("we are here!").[5]

Remove ads

Early doikayt thought

Summarize

Perspective

The origins of doikayt have also been linked to much earlier thought, to figures such as Chaim Zhitlowsky, S. An-sky, and Simon Dubnow.[16] According to some scholars, already in 1883 in Vitebsk (today's Belarus), Zhitlowsky linked "Jewish national revival with socialist revolutionism",[20] where "[t]his search for a synthesis contains essential elements of do’ikayt, and of the Bund's eventual platform: the struggle for social change must take place in the here and now (as the socialists believed), and Jews must and can participate as Jews in that struggle (as the proto-Zionists believed)."[21]: 10

Zhitlowsky's contemporary, S. An-sky, can be seen as a representative of doikayt through his participation in both Jewish and non-Jewish Russian life and struggles[21]: 14-15 , for example by his commitment to addressing the material needs of Jewish victims during World War I, at the same time as preserving and promoting Jewish and Yiddish culture.[6] An-Sky's writing, which presented the "rootedness" of Jewish life, its link to place in Eastern Europe, and the emphasis on the conditions of poor and working Jews, has been termed "literary doikayt".[6]

Simon Dubnow, the founder of the Folkspartei,[22] is another representative of early doikayt thought[21]: 14 . Dubnow advocated for Diaspora nationalism, calling for the preservation of Yiddish and Jewish culture through maintaining a Jewish cultural autonomy in Eastern Europe.[22] Dubnow encouraged Jews to self-study, maintain their folk material and heritage, be active in improving Jewish life and promote an Indigenous national culture[21]: 21-22 .

Remove ads

Contemporary doikayt

In the late 20th and early 21st century, doikayt has been embraced by various progressive Jewish groups, especially in America. Jews for Racial and Economic Justice (JFREJ, established in New York City in 1990) have embraced doikayt, stating: “Where we are is our home. This is what we fight for. This is where we seek kinship".[23] The founding director of JFREJ, Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz, wrote on 2007: "Doikayt means Jews enter coalitions wherever we are, across lines that might divide us, to work together for universal equality and justice".[1][24] Jewish Currents magazine, founded in 1946 and relaunched in 2018, dedicated its first post-relaunch issue to "Diasporism", which it also linked to doikayt.[23][25] In 2025, Naomi Klein and Astra Taylor wrote of doikayt: "Perhaps what is needed is a modern-day universalization of that concept: a commitment to the right to the “hereness” of this particular ailing planet, to these frail bodies, to the right to live in dignity wherever on the planet we are, even when the inevitable shocks forces us to move. “Hereness” can be portable, free of nationalism, rooted in solidarity, respectful of indigenous rights and unbounded by borders."[26]

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads