Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

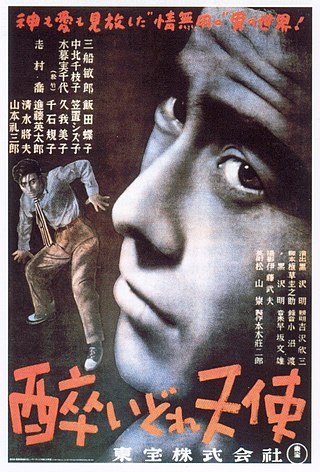

Drunken Angel

1948 Japanese film From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Drunken Angel (醉いどれ天使, Yoidore Tenshi) is a 1948 Japanese yakuza film directed by Akira Kurosawa, and co-written by Kurosawa and Keinosuke Uekusa. Starring Takashi Shimura and Toshiro Mifune, it tells the story of alcoholic doctor Sanada, and his recidivist yakuza patient Matsunaga. Sanada tries to prevent Matsunaga from destroying his body while Matsunaga finds himself gradually confronted with the brutal realities of yakuza life.

Production began in 1947 amid a series of labour disputes in the Toho company. Filming lasted from November to March 10 1948. During the production of the film Kurosawa encountered a number of setbacks, including the death of his father in February 1948. The film was released in Japan on April 27 1948. The film was the first of sixteen film collaborations between director Kurosawa and actor Toshiro Mifune and is generally considered to be Kurosawa's first major work.

Remove ads

Plot

Summarize

Perspective

Sanada is an alcoholic doctor living in a shanty town next to an open sump. He treats a small-time yakuza named Matsunaga—who was injured in gunfight with a rival syndicate—despite his dislike of organised crime. Sanada diagnoses Matsunaga with tuberculosis; Matsunaga initially reacts violently but the two of them are interrupted by the arrival of Sanda's nurse Miyo. The following day Sanada goes to a bar in the local black market, which Matsunaga exercises control over, and attempts to persuade Matsunaga to give up drinking and smoking. After Matsunaga kicks Sanada out of the bar, Sanada and Miyo discuss the imminent release from prison of Matsunaga's fellow yakuza and sworn brother, Okada, Miyo's abusive ex-boyfriend. Sanada continues treating his other patients, one of whom, a young female student, is making progress against her tuberculosis. After some pestering, Matsunaga agrees to listen to the doctor's advice and quit drinking.

However, with Okada's release, Matsunaga quickly succumbs to peer pressure and slips back into vice together with his fellow yakuza. Angered at the betrayal of his commitment, Sanada rebukes him. Matsunaga finds himself gradually displaced within the yakuza syndicate, and after losing a large amount of money playing chō-han, he collapses and is taken to Sanada's clinic for the evening. Distressed as his lover leaves him and his illness takes a turn for the worse, Matsunaga leaves his apartment and is confronted by Sanada at the open sump. Sanada beseeches Matsunaga to continue his treatment, while Matsunaga has a vision of his own corpse trying to kill him. Okada shows up at the clinic and threatens to kill the doctor if he does not tell him where to find Miyo, and while Matsunaga stands up for the doctor and gets Okada to leave, he realises that his sworn brother cannot be trusted.

Hoping to seek resolution to the issue, Matsunaga goes to the home of the boss of his syndicate but overhears a discussion with Okada that he intends to sacrifice him as a pawn in the war against a rival syndicate. Distressed and self-destructive, Matsunaga orders a drink from a local barmaid who tries to persuade him to seek treatment in the countryside. The boss returns the territory of the black market to Okada, who orders the storeowners in his territory to refuse service to Matsunaga. He goes to Okada's apartment, there, he finds the yakuza with his former lover, and angrily tries to stab Okada, but starts to cough up blood; Okada then stabs him in the chest, and Matsunaga stumbles outside before he succumbs to his wounds and dies.

Okada is later arrested for the murder, but Matsunaga's boss refuses to pay for his funeral. The barmaid, who had feelings for Matsunaga, pays for it instead and tells Sanada that she plans to take Matsunaga's ashes to be buried on her father's farm, where she had offered to live with him. The doctor retorts that while he understands how she feels, he cannot forgive Matsunaga for throwing his life away. Another of his patients, the female student, arrives and reveals that her tuberculosis is cured. The doctor happily leads her to the market to buy her sweets.

Remove ads

Cast

- Takashi Shimura as Doctor Sanada

- Toshiro Mifune as Matsunaga

- Reizaburo Yamamoto as Okada

- Michiyo Kogure as Nanae

- Chieko Nakakita as Nurse Miyo

- Eitarō Shindō as Takahama

- Noriko Sengoku as Gin

- Shizuko Kasagi as Singer

- Masao Shimizu as Oyabun

- Yoshiko Kuga as Schoolgirl

Production

Summarize

Perspective

Development

Drunken Angel was made in the context of a series of labor disputes with the Toho company. The powerful trade union had managed the production of films, with Kurosawa's prior films No Regrets for Our Youth and One Wonderful Sunday requiring the approval of the union. By the end of 1947, the union influence that had been exerted over the content of films produced by Toho began to wane following a series of less profitable releases. As a result, Kurosawa was able to produce the film with minimal interference from the studio and its union.[1] Kurosawa co-wrote the film with his childhood friend Keinosuke Uekusa in their second collaboration together.[2] While staying at an inn at the seaside resort Atami, Kurosawa noticed that the prow of a sunken concrete ship was being used as a diving board by local children. Seeing it as an apt metaphor for Japan's defeat in the Second World War, this image became the open sump seen in Drunken Angel.[3] Kurosawa intended to write the film to report on—and denounce—the growing power of the yakuza in post–War Japan.[4][5]

During writing of the screenplay, Uekusa met up with a yakuza life-model to develop the character of Matsunaga; while he and Kurosawa had intended for his counterpart to be a morally upright humanistic young doctor, the character was difficult to conceptualise and was changed when the two remembered an encounter they had with an unlicensed alcoholic doctor in Tokyo's black market district.[6] Having spent five days prior to the doctor's change in character unsure of how to progress the script, they finished writing the film in about a day.[7] However, Uekusa's meetings with the yakuza character model caused him to sympathise with their way of life to the degree that he and Kurosawa eventually argued over his sympathies.[8] Despite the speed with which the two of them finished the script, Kurosawa recalled the two of them sharing a rocky relationship during its development. Although they remained friends, the two of them separated and did not collaborate again following the script's completion.[9]

Pre-production

Pre-production began in November 1947.[10] Toshiro Mifune was cast after Kurosawa saw his performances in Snow Trail (1947) and Kajirō Yamamoto's These Foolish Times (1947).[11][12] Kurosawa had seen Mifune's audition to work at the Toho company in 1946 and had directly intervened in the hiring process in order to secure Mifune a position; the jury had wrongly interpreted the actor's wild behaviour during the audition as disrespect.[13] The film was built around a pre-existing set, used in These Foolish Times.[1] This set was of a shopping street with a black market, which Kurosawa credits for the origin of his interest in dissecting the character of yakuza gang members.[8]

Production

The film was produced by Toho and shot in black-and-white.[14] Filming began in November 1947.[10] During the course of production, Kurosawa faced a number of personal and professional problems. Toho executives pressured Kurosawa to finish production quickly, anxious to see more films in cinemas before any more potential strikes, and actress Keiko Orihara became ill shortly into production—she was replaced by Chieko Nakakita in January 1948. Additionally, in February, Kurosawa's father Isamu died at the age of 83. Kurosawa felt too pressured to be able to return to Akita Prefecture during the final weeks of shooting to be with his father.[10]

Takashi Shimura loosely based his character of the doctor on the performance of Thomas Mitchell in Stagecoach (1939). Despite Shimura's role as the protagonist, Kurosawa later expressed difficulty in being able to contain Mifune's performance as the gangster so that he did not dominate the film with his screen presence.[11] Kurosawa also praised the acting of Reizaburo Yamamoto, although he described being too afraid to approach him for some time due to his "frightening eyes".[15] Filming ended on March 10 1948.[11] A 150-minute cut of the film was made but never released; all existing negatives and prints are of the 98 minute cut.[14]

Music

Drunken Angel marked Kurosawa's first collaboration with composer Fumio Hayasaka. The two agreed on much of the film's composition. Kurosawa wrote memos (published in the April 1948 edition of Eiga Shunshu) that detailed his changing attitude towards the use of music in his films, becoming more conscious of its inclusion by matching it to parts of the script during the film's writing.[16] For Okada's introductory scene, Kurosawa and Hayasaka wanted to use the song "Mack the Knife" from The Threepenny Opera, but found that it was copyrighted and the studio was unwilling to pay for the rights.[17][18] The use of cheerful-sounding song "The Cuckoo Waltz" was designed to juxtapose the film's low-point of Matsunaga being rejected from different neighbourhood establishments.[18] Kurosawa thought to use this song when, on the day he received news of his father's death, he heard the music over a loudspeaker and found that it intensified his own grief.[19] Supposedly the director and composer shook hands after discovering that they had had the same idea separately but simultaneously. The film's sound recorder was Wataru Konuma.[18]

Occupation censorship

At the time of Drunken Angel's production, there were limitations placed on Japanese films by the Allied occupation government. Films were encouraged to promote individual liberties and Japan's demilitarisation, while forbidden from promoting nationalistic or feudal values. From 1946, the Civil Information and Education Section enforced a double censorship of completed scripts during pre-production and completed films following the final edit.[20] The occupation's censors required Kurosawa to rewrite several portions of the film mostly due to ethical concerns; for example, a mention of suicide was cut, and complaints were made concerning the film's frank depiction of prostitution and black markets.[21] The film's ending was also changed, originally the doctor Sanada drove Matsunaga's corpse around the Tokyo slum.[22][23] Matsunaga's manner of death also underwent several re-writes within each of which he was killed by different people.[22]

Remove ads

Themes

Summarize

Perspective

Post–War dual identity

In his study of Kurosawa's filmography, Stuart Galbraith IV sees the gangster Matsunaga and doctor Sanada as linked by their illness. To Sanada, Matsunaga represents the "chaotic temptations of postwar Japan", which Sanada relates to his own past behaviour. However, Matsunaga equally stands for the corrupt criminality of the period's social chaos that Sanada reviles.[24] Galbraith believes that the doctor is the film's titular 'drunken angel' for seeking the improvement of others over himself despite his self-hatred.[25] Matsunaga is also paired with various women in the film, he shares a relationship with his old yakuza boss to Sanada's nurse Miyo, although she resists returning to her old life; additionally, one of Sanada's patients is also afflicted with tuberculosis, but is able to overcome her illness. Both Matsunaga and Sanada have women that love and care for them in what Galbraith terms a "Hitchcock-like parallelism".[26]

The film scholar James Goodwin's perspective on the film's dual identity is informed by his reading of the psychological doubling between Matsunaga and Sanada. He recalls Sanada's paradoxical commitment to alleviating his patients' illnesses which ends their need for his services, while he himself remains unhealed. Similarly, when his condition deteriorates, Matsunaga hallucinates raising his own corpse from a coffin, only to be scorned by it. Both characters are positioned as sharing, "a vital [emotional] bond."[28] Goodwin, Galbraith, and the film critic Mark Schilling, each view the open sump as a representative of the desolate post–War world.[29][10][30] However, Galbraith sees in the sump an additional psychological dimension, viewing the characters' reflections on the murky water as an indication of their state, with Matsunaga throwing his carnation away being a symbol that he has discarded his life.[10]

Stephen Prince, in his analysis of Kurosawa's filmography, considers the "double loss of identity" present within the film. One loss implying a reformation of social identity whereby the progressive individual should separate themselves from the family (embodied in the yakuza), and the other being symptomatic of a "national schizophrenia" that has resulted from the Americanisation of Japan.[31] In the film the young are cut off from the past but still bound by its social mores. Prince writes that the narrative and spatial confinement of much of the film close to the sump returns the action to sickness, posing the question of how recovery can emerge from a humane ethic under post-war conditions.[27]

Intertextuality

Film theorist David Desser points to Drunken Angel as an early example among Kurosawa's films of demonstrating how Western culture impacted Japanese society; i.e., that it represents an adaptation of different modes of thought from American gangster stories and the existentialist literature of Fyodor Dostoevsky.[32] Similarly, Goodwin writes on the intertextual qualities of the film and Kurosawa's references to different artistic mediums. He considers the final fight between Matsunaga and his rival among spilt paint to be a kind of "action painting" and also compares Drunken Angel's literary qualities to the novels of Dostoevsky.[33] In particular, Goodwin focusses on a process of psychological doubling found in Dostoevsky's novels, wherein internal paradoxes and contrasting personalities—such as those of Matsunaga and Sanada—form a dialogue on suffering and human nature.[34]

Remove ads

Release

Summarize

Perspective

Theatrical

Drunken Angel was released in Japanese cinemas on April 27 1948.[18] Upon the film's completion, Kurosawa went to Akita to observe the memorial services of his father, but was recalled as the Toho union's strikes had escalated.[35] The new company president, Tetsuzo Watanabe, vetoed union-supported films and fired 1,200 employees. In response, the union occupied the building, halting production on new films. The strikers were placed under siege by police and the American military, the studio ended their pay, and shut down the filming lot on June 1. In need of money, Kurosawa directed two stage productions, one of Anton Chekhov's A Marriage Proposal, and the other an adaptation of Drunken Angel.[36] Kurosawa soon left the studio, being both disillusioned by executives' attitudes to the union, and by the state of siege the occupying strikers were put under. In his memoir Kurosawa writes that the studio, "I had thought was my home actually belonged to strangers".[37]

The film was one of only four productions that Toho released in 1948, reflecting the studio management's priorities amidst disruptive strike action.[38] Toho promoted the release of the film throughout the 1950s, with it premiering in the United States in January 1960 as part of a nine-film release licensed by Brandon Films.[18]

Remove ads

Reception

Summarize

Perspective

Critical response

Contemporary opinion

Upon release in Japan, the film received positive reviews.[18] However, there were some critics who did not believe the film went far enough in condemning the activities of its protagonist or the yakuza world at-large.[39] According to Kurosawa, critics referred to him as a journalistic filmmaker.[40] Japanese audiences were surprised by Mifune's emotional performance, a form of expressiveness that was not generally seen in Japanese cinema of the time. Galbraith compares the impact of, and audiences' positive reaction to, Mifune's performance with Marlon Brando's in A Streetcar Named Desire (1951).[11] Japanese critics have pointed to Drunken Angel as embodying the post–War epoch in Japanese society, with comparisons made to Bicycle Thieves (1948) and Paisan (1946).[41]

Writing just prior to the American release, Bosley Crowther's 1959 review for The New York Times, cites the film's creation of an unpleasant atmosphere in his positive appraisal of its symbolic moral conflict. He also gives a positive account of the acting and Kurosawa's "forceful imagery", despite criticising some of the film's unoriginal formal methods and clichés.[42] A review in Variety magazine compared Drunken Angel to Italian neorealist cinema in its depiction of contemporary Japanese society; the review also praised the film's acting and pursuit of morality within the post–War devastation.[18] However, a negative review by Dwight Macdonald in Esquire negatively compared the film to the simultaneous American releases of Ikiru (1952) and The Men Who Tread on the Tiger's Tail (1945), criticising the film as an "embarrassingly familiar gangster melodrama."[43]

Retrospective opinion

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, Drunken Angel has a 93% approval rating.[44]

Awards and accolades

Remove ads

Legacy

Summarize

Perspective

Drunken Angel is often considered Kurosawa's first major work.[1][41] The director later reflected on the film's structural weakness which he mostly attributed to Mifune's intense screen-presence, one which overshadowed Shimura's role as the moral centre of the film.[46] However, he saw it as the first film where he began to think about the image's relationship to music, and remembered it happily as the first film that was his own, i.e., the first that was free from the interference of the studio, union, and wartime censorship.[47][41] In a 1960 interview with Donald Richie, Kurosawa considered the film's popularity at the time of its release to be due to it being the only film in cinemas that took an interest in its characters.[40] He later referred to Drunken Angel as the first of his films that used dynamic compositions.[48]

In Mark Schilling's study on yakuza films, he cites Drunken Angel as the first to depict post–War yakuza. Schilling notes that the film does not follow many of the genre expectations within the genre, which he attributes to Kurosawa's humanism, examining how the world around the yakuza influences their actions.[49] In a 2002 interview, actor Bunta Sugawara likewise referenced the film as the first post–War yakuza movie.[50]

Remove ads

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads