Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Thomas Edison

American inventor and businessman (1847–1931) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Thomas Alva Edison (February 11, 1847 – October 18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, sound recording, and motion pictures. These inventions, which include the phonograph, the motion picture camera, and early versions of the electric light bulb, have had a widespread impact on the modern industrialized world. He was one of the first inventors to apply the principles of organized science and teamwork to the process of invention, working with many researchers and employees. He established the first industrial research laboratory.

Edison was raised in the American Midwest. Early in his career he worked as a telegraph operator, which inspired some of his earliest inventions. In 1876, he established his first laboratory facility in Menlo Park, New Jersey, where many of his early inventions were developed. He went into business and became wealthy. Edison used his fortune to further his passion for invention. This was realized in experimental mining operations, the first film studio, and 1,093 US patents.

Remove ads

Early life

Summarize

Perspective

Thomas Edison was born in 1847 in Milan, Ohio, but grew up in Port Huron, Michigan, after the family moved there in 1854.[1] He was the seventh and last child of Samuel Ogden Edison Jr. (1804–1896, born in Marshalltown, Nova Scotia) and Nancy Matthews Elliott (1810–1871, born in Chenango County, New York).[2][3] His patrilineal family line was Dutch by way of New Jersey.[4]

His great-grandfather, loyalist John Edeson, fled New Jersey for Nova Scotia in 1784. The family moved to Middlesex County, Upper Canada, around 1811, and his grandfather, Capt. Samuel Edison Sr. served with the 1st Middlesex Militia during the War of 1812. His father, Samuel Edison Jr. moved to Vienna, Ontario, and fled to Ohio after his involvement in the Rebellion of 1837.[5]

Edison was taught reading, writing, and arithmetic by his mother, a former school teacher. He attended school for only a few months but was a very curious child who learned most things by reading on his own.[6] Inspired by A School Compendium of Natural and Experimental Philosophy, a book given to him by his mother, the young Edison tinkered and learned about electricity.[7][8]: 30 His parents also owned a book by Thomas Paine, whose work inspired Edison's thinking throughout his life.[9][8]: 30

Edison developed hearing problems at the age of 12. Historian Paul Israel attributed the cause of his deafness to a bout of scarlet fever during childhood and recurring untreated middle-ear infections. He subsequently concocted elaborate fictitious stories about the cause of his deafness.[10][11]: 17 He was completely deaf in one ear and barely hearing in the other. Edison later listened to a music player or piano by clamping his teeth into the wood to absorb the sound waves into his skull.[8]: 552 As an adult he believed his hearing loss allowed him to avoid distraction and concentrate more easily on his work.[11]: 17 [12]

Edison began his career as a news butcher, selling newspapers, candy, and vegetables on trains running from Port Huron to Detroit.[13] He turned a $50-a-week profit by age 13, most of which went to buying equipment for electrical and chemical experiments.[8]: 584 He founded the Grand Trunk Herald, which he sold with his other papers. The paper only ran twenty-four issues and was unique in its original coverage of local news. Five hundred people subscribed to the paper, and Edison was able to hire at least two assistants.[14][15] Edison was proud of his work on the train,and he hung a frame with the first issue of the Grand Trunk Herald in his home until he died.[16]

At age 15, in 1862, he saved a child from being struck by a runaway train.[17] The father was so grateful that he trained Edison as a telegraph operator. He began working as a telegrapher in a local general store before moving to Stratford Junction, Ontario, where he worked as a night telegrapher for the Grand Trunk Railway.[18] While on the job, he studied qualitative analysis, conducted chemical experiments, [14] and negligently slept. This led to the near collision of two trains after which he resigned.[19][14]

Remove ads

Telegraphy

Summarize

Perspective

From 1863 to 1869 Edison worked several night shift telegraphy jobs in Ontario, Michigan, Kentucky, Ohio, and Massachusetts. As an employee of Western Union, he worked the Associated Press bureau news wire. In Cincinnati, he lived with Ezra Gilliland with whom he remained friends for 25 years. He joined the National Telegraph Union and wrote for their magazine. In addition to spending his time tinkering, he studied Spanish. He created a reputation among the other young, male telegraph operators for being bright and trying new things, but on several occasions his tinkering interfered with his work.[20][11]: 23, 28–31

In Boston, from 1867 to 1869, Edison made some money from inventing a stock ticker for some local customers but lost it when he tried to expand the venture to New York without adoption.[21]

His first patent was for the electric vote recorder, U.S. patent 90,646, which was granted on June 1, 1869.[22]

Edison moved to New York City in 1869. One of his mentors during those early years was a fellow telegrapher, Franklin Leonard Pope, who allowed the impoverished young Edison to live and work in the basement of his Elizabeth, New Jersey, home while Edison worked for Samuel Laws at the Gold Indicator Company. Pope and Edison founded their own company in October 1869, working as electrical engineers. Edison attracted wealthy and connected investors. With the money, they hired fifty employees within a few months and opened a larger shop in Newark, New Jersey. The company made money by renting out telegraph lines. To win business, they manufactured machines to record telegraphs and typewriters that printed directly to the wire. Edison strictly regulated his employees’ work and efficiency while trying many experiments.[24]

Edison enrolled in a chemistry course at The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art to support his work on a new telegraphy system with Charles Batchelor. This appears to have been his only enrollment in courses at an institution of higher learning.[25] At the factory, Edison and Batchelor collaborated fervently; their notebooks jointly signed "E&B" contain near constant experimentation with improvement to the telegraph.[26]

Edison grew the company to a few hundred employees, and in 1874, received $30,000 ($833,735 in 2024) for inventing the first telegraph which could simultaneously transmit four messages through a single wire.[27][28][29] With the money, Edison invested in the Port Huron street railway which was owned his brother William Pitt.[29][11]: 61 He expanded his own business, and he hired his young nephew and father.[29]

Remove ads

Menlo Park laboratory

Summarize

Perspective

Research and development facility

In Menlo Park, New Jersey, Edison created the first industrial laboratory concerned with creating knowledge and then controlling its application.[30] It was built in 1876, a part of Raritan Township (now named Edison Township in his honor) with the funds from the sale of Edison's quadruplex telegraph. His staff was generally told to carry out his directions in conducting research, and he drove them hard to produce results.[8]: 374–376, 499 Edison's name is registered on 1,093 patents.[31] As the leader of his laboratory, Edison was credited for inventions made in large part by those working under him. He worked extreme hours and expected those around him to follow suit. This often meant 18 hours per day Monday through Friday and additional work on Saturday and Sunday. One employee described the work as "the limits of human exhaustion."[11]: 192 Edison often litigated and employed several patent lawyers. At times, this allowed him to challenge the intellectual property rights of many contemporaries.[8]: 236, 237, 246, 247, 250–253, 295, 382 [32]

For Edison, big business came with big publicity. He shut down public and reporter access to the laboratory at Menlo Park and tailored his image with interviews. He expanded his public involvement by funding the creation of Science which published its first volume in 1880. He was the chief editor but kept his role anonymous. The journal began as a mouthpiece for pro-Edison articles. He gave up the journal in 1883 due its lack of profit. It was subsequently led by Alexander Graham Bell.[33]

In just over a decade, Edison's Menlo Park laboratory had expanded to occupy two city blocks. Edison said he wanted the lab to have "a stock of almost every conceivable material".[34] In 1887 the lab contained "eight thousand kinds of chemicals, every kind of screw made, every size of needle, every kind of cord or wire, hair of humans, horses, hogs, cows, rabbits, goats, minx, camels ... silk in every texture, cocoons, various kinds of hoofs, shark's teeth, deer horns, tortoise shell ... cork, resin, varnish and oil, ostrich feathers, a peacock's tail, jet, amber, rubber, all ores ..." and the list goes on.[35]

Carbon telephone microphone

In 1876, Edison began work to improve the microphone for telephones by developing a carbon microphone, which consists of two metal plates separated by granules of carbon that would change resistance with the pressure of sound waves.[11]: 132–141

In 1877, Edison, and his backers at Western Union wanted to compete with the Alexander Graham Bell on telephone technology. Edison believed that the worst part of Bell's telephone was the microphone designed by Emile Berliner. Edison iterated many different designed and tested which gave the best sound while ensuring it was loud enough for his deaf ears. His core idea was to use stronger current and vary it in proportion to the sound waves. The sound varied the current by applying pressure to a carbon pad which in turn changed the resistance of the circuit. After testing 150 materials, Edison determined that parchment and tinfoil were best suited for constructing the diaphragm, while a specially coated rubber served as the semiconductor.[11]: 132–141, 425

David Edward Hughes' also published a paper on the physics of loose-contact carbon microphones in 1878. He claimed, and at the time was credited for, discovering the semi-conductor effect and presented a Hughes Telephone. This angered Edison and caused public controversy, particularly because Hughes acknowledged that he was advised by one of Edison's colleagues.[11]: 141–158

Phonograph

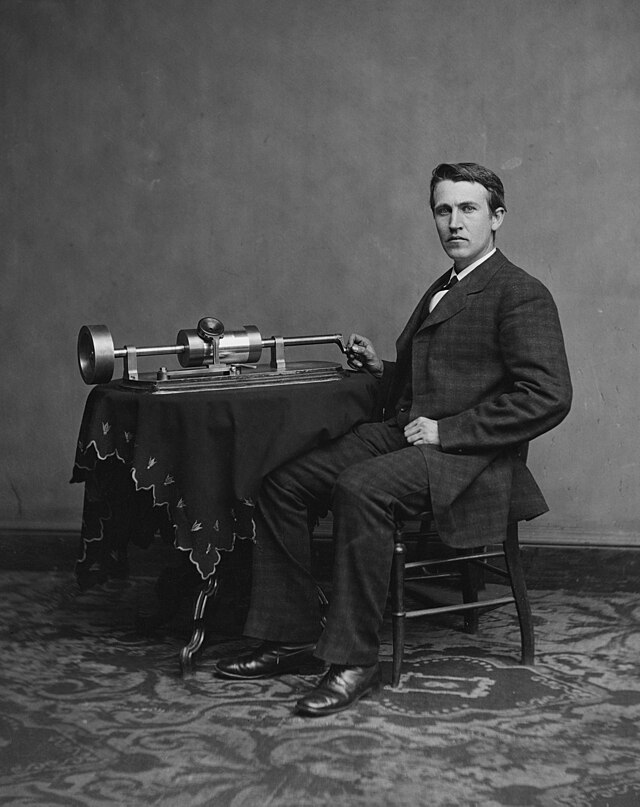

The invention that first gained him wider notice was the phonograph in 1877.[36] He vigorously stirred up public awareness for this new invention by engaging with journalists and performing public demonstrations.[37] The phonograph was so unexpected by the public at large as to appear almost magical. Edison became known as "The Wizard of Menlo Park".[38] As he aged, he grew to resent titles representing him as a genius, and he emphasized "one percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration."[8]: 59

His first phonograph recorded on tinfoil around a grooved cylinder. Despite its limited sound quality and that the recordings could be played only a few times, the phonograph made Edison a celebrity. Joseph Henry, president of the National Academy of Sciences and one of the most renowned electrical scientists in the US, described Edison as "the most ingenious inventor in this country... or in any other".[39] In April 1878, Edison demonstrated the phonograph before the National Academy of Sciences.[40] Although Edison obtained a patent for the phonograph in 1878,[41] he did little to develop it until Alexander Graham Bell, Chichester Bell, and Charles Tainter produced a phonograph-like device in the 1880s that used wax-coated cardboard cylinders.[42]

In 1887, the Edison Phonograph Company was founded to compete with Bell. Gilliland had worked for Bell developing the phonograph but came help Edison start the new venture. Unfortunately for their friendship, the venture ran out of money before getting a product to market and had to raise money from an exploitative investor. Jesse Lippincott offered simultaneous deals to Edison, Gilliland, and Bell in an attempt to form a phonograph monopoly. However, he knew Edison would not take the bargain, so obfuscated his own, Gilliland's, and Bell's roles in the deal and made the offer through Edison's personal attorney. When Edison discovered the scheme, he was infuriated, but Gilliland went to Europe which ended their friendship. After five years of litigation, Edison assumed total control of the company. The drama led to multiple other fall outs that tore apart the tight circle of Edison's wealthy inventor-friends.[43]

Edison struggled for years to bring a phonograph to market. The principal technical issue was getting the recording material durable enough for prolonged use without it wearing out the phonograph's needle.[44] He attempted to pivot to making talking dolls with a miniature phonograph inside. However, the system usually failed during shipment and production was shutdown in 1890.[45] Edison thought that the phonograph would be a powerful instrument for conducting business and would redefine the role of secretaries. However, by 1899 Edison's phonograph company submitted to market demands and produced a cheap model that was in high demand for entertainment. In 1900, this phonograph was sold for $10 and buyers could additionally select from the 3,000 different musical records produced by Edison's 1,000 employees in the phonograph works. The quality of line work was strictly supervised by experts.[46]

Edison had no musical training, could not read sheet music, and was mostly deaf. Through 1915, he exerted tight control on the production of records personally approving every artist based on what he thought sounded good and preventing their names from being attached to the music.[47]

Widespread adoption of the radio was detrimental to phonograph sales. Edison's business sold 90% fewer records in 1921 compared to 1920. From 1922 to 1926 radio sales went up 843%. Younger managers, especially his son Charles, tried to get Edison to enter the radio business or adopt new advertising methods. However, Edison chose to focus on weeding out employees that did not meet his mark.[48]

Tasimeter

Edison invented a highly sensitive device, that he named the tasimeter, which measured infrared radiation. His impetus for its creation was the desire to measure the heat from the solar corona during the total Solar eclipse of July 29, 1878.[49][50]

Remove ads

Electric light

Summarize

Perspective

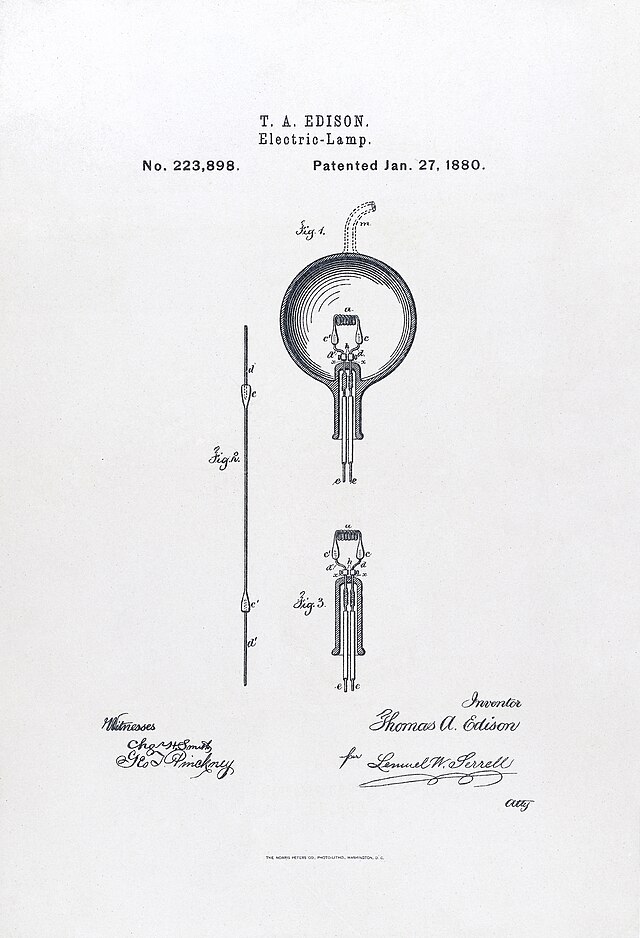

In 1878, Edison began working on a system of electrical illumination that he could deploy in a large scale commercial utility, something he hoped could compete with gas and oil-based lighting.[51] Key to his system would be developing a durable low resistance incandescent lamp, essential for a wide scale indoor lighting system. There had been many incandescent lamps devised by inventors prior to Edison, but these early bulbs all had flaws such as an extremely short life and requiring a high electric current to operate which made them difficult to apply on a large scale commercially.[11]: 217–218 Edison first tried using a filament made of cardboard, carbonized with compressed lampblack. This burnt out too quickly to provide lasting light. He then experimented with different grasses and canes such as hemp, and palmetto, before settling on bamboo as the best filament.[52][11]: 196–197

He addressed lighting as a system.[11]: 190 Solving it took experimental research; market research, with Grosvenor Lowrey that included forging connections with powerful investors, viewing a mechanical electric generator, and planning power distribution; and grand public statements to promote his work.[53] Edison formed the Edison Electric Light Company in New York City with several financiers, including J. P. Morgan, Spencer Trask,[54] and the members of the Vanderbilt family.

Edison continued trying to improve this design and on November 4, 1879, filed for U.S. patent 223,898 (granted on January 27, 1880) for an electric lamp using "a carbon filament or strip coiled and connected to platina contact wires".[55] The patent described several ways of creating the carbon filament including "cotton and linen thread, wood splints, papers coiled in various ways".[55] It was not until several months after the patent was granted that Edison and Batchleor discovered that a carbonized bamboo filament could last over 1,200 hours.[55][8]: 384 This high resistance filament led Edison to select the 110V power source standard in the United States today. This was much higher voltage than what competitors were using.[8]: 384, 385, 422 Many of his employees assisted in carrying out experiments on filaments, manufacturing the glass for the bulbs, and establishing vacuums for the filament to incandesce within.[8]: 375, 383–385 By February 1880, spectators were coming to see the "Village of Light" around Menlo Park.[8]: 363

Attempts to prevent blackening of the bulb due to emission of charged carbon from the hot filament[56] culminated in Edison effect bulbs.[57] Edison's 1883 patent for voltage-regulating[58] is the first US patent for an electronic device due to its use of an Edison effect in an active component.[8]: 438–439 The Edison Effect was instrumental in the eventual design of vacuum tubes.[56]

Edison hired Francis Robbins Upton a former student of Hermann von Helmholtz in 1878.[59][8]: 375–376 Upton received 5% of the company profits and eventually became the general manager after leading much of the research into electric lighting.[59][60] He wrote some of Edison's speeches and assisted with hiring decisions.[59] John Ott also worked for Edison. He made many of the mechanical improvements Edison suggested and conducted experiments in Edison's lab. Both men agreed to give Edison credit for most of the patents, but Ott was solely credited for some of the patents he worked on. Ott's testimony was important for holding up Edison's patent claims.[11]: 199–200 John's brother, Fred, also worked for Edison as an experimental assistant for fifty-seven years.[61]

Henry Villard, president of the Oregon Railroad and Navigation Company, attended Edison's 1879 demonstration. Villard was impressed and requested Edison install his electric lighting system aboard the Columbia. Although hesitant at first, Edison agreed to Villard's request. Most of the work was completed in May 1880, and the Columbia went to New York City, where Edison and his personnel installed Columbia's new lighting system. The Columbia was Edison's first commercial application for his incandescent light bulb.[8]: 378–380 The Edison equipment was removed from Columbia in 1895.[62][63][64]

Villard was subsequently induced to finance the construction of an electrically powered and lighted train built on a custom track built by Edison's company. The train worked and some of the technology was patented, but Edison elected to focus on the bulbs and did not follow through with developing the train.[8]: 380–382

The incandescent light bulb patented by Edison began to gain widespread popularity in Europe as well. He sent engineers to promote their system, first to London, then around Europe.[8]: 418–419

On September 4 1882, Edison turned on the system to supply the company's 946 customers in Manhattan. Few people noticed, some came in the evening to ask why the system was not on yet. The lights were so steady and so similar to the gas people were used to that they had not noticed the switch. There was little press but the Boston Globe stated,

Edison has had an 'opening night.' His aim is to open night until it shall be as day.[8]: 424–426

In 1883, the US patent office ruled that Edison's patented filament improvement process was based on Sawyer's flashing method and was, therefore, invalid.[11]: 316 Edison's company modified their improvement process until 1889 when a judge ruled that their new patent was valid.[65] To avoid a possible court battle with yet another competitor, Joseph Swan, who held an 1880 British patent on a similar incandescent electric lamp,[66] formed a joint company called Ediswan to manufacture and market the invention in Britain. Sawyer's original filament improvement process was better and Westinghouse, which owned rights to Sawyer's patent, was able to take a sizeable portion of the bulb market share from Edison by 1889.[11]: 320, 323

Electric power distribution

After devising a commercially viable electric light bulb on October 21, 1879, Edison developed an electric utility to compete with the existing gas light utilities.[67] To prove he was making progress, Edison hosted a board meeting which was illuminated by his system.[68] On December 17, 1880, he founded the Edison Illuminating Company, and during the 1880s, he patented a system for electricity distribution.[8]: 395, 422

The amount of copper wire needed to commercialize this new technology was enormous. In order to reduce the copper requirement, Edison invented the three-prong wire system.[8]: 422

To expand its influence in New York, especially to secure the rights for installing underground electric lines, the Edison Illuminating Company opened a second office on 65th Avenue. The Edison Machine Works and Edison Electric Tube company opened in New York by the end of the year.[69] Edison paid his New York workers significantly more than other firms in the 1880s.[70] Before fully commercializing power distribution, Edison needed a way to measure how much power his customers consumed. He invented a cell with a zinc solution and zinc plates that received some of each customer's current. This resulted in zinc from the solution precipitating onto the plates which were weighed on a monthly basis to determine how much current had passed through and bill the customer accordingly.[71]

In January 1882, to demonstrate feasibility, Edison had switched on the 93 kW first steam-generating power station at Holborn Viaduct in London. On September 4, 1882, in Pearl Street, New York City, his 600 kW cogeneration steam-powered generating station, Pearl Street Station's, electrical power distribution system was switched on, providing 110 volts direct current (DC). Subscriptions quickly grew to 508 customers with 10,164 lamps.[70]

Expansion and competition

As Edison expanded his direct current (DC) power delivery system, he received stiff competition from companies installing alternating current (AC) systems. From the early 1880s, AC arc lighting systems for streets and large spaces had been an expanding business in the US. With the development of transformers in Europe and by Westinghouse Electric in the US in 1885–1886, it became possible to transmit AC long distances over thinner and cheaper wires, and "step down" (reduce) the voltage at the destination for distribution to users. This allowed AC to be used in street lighting and in lighting for small business and domestic customers, the market Edison's patented low voltage DC incandescent lamp system was designed to supply.[72] Edison's DC empire suffered from one of its chief drawbacks: it was suitable only for the high density of customers found in large cities. Edison's DC plants could not deliver electricity to customers more than one mile (1.6 km) from the plant, and left a patchwork of unsupplied customers between plants. Small cities and rural areas could not afford an Edison style system, leaving a large part of the market without electrical service.[73] AC companies expanded into this gap.[74]

Edison expressed views that AC was unworkable and the high voltages used were dangerous. As George Westinghouse installed his first AC systems in 1886, Thomas Edison struck out personally against his chief rival stating,

Just as certain as death, Westinghouse will kill a customer within six months after he puts in a system of any size. He has got a new thing and it will require a great deal of experimenting to get it working practically.[75]

Many reasons have been suggested for Edison's anti-AC stance. One notion is that the inventor could not grasp the more abstract theories behind AC and was trying to avoid developing a system he did not understand. Edison also appeared to have been worried about the high voltage from improperly installed AC systems killing customers and hurting the sales of electric power systems in general.[76] The primary reason was that Edison Electric based their design on low voltage DC, and switching a standard after they had installed over 100 systems was, in Edison's mind, out of the question. By the end of 1887, Edison Electric was losing market share to Westinghouse, who had built 68 AC-based power stations to Edison's 121 DC-based stations. To make matters worse for Edison, the Thomson-Houston Electric Company of Lynn, Massachusetts (another AC-based competitor) built twenty-two power stations.[77]

Parallel to expanding competition between Edison and the AC companies was rising public furor over a series of deaths in the spring of 1888 caused by pole mounted high voltage alternating current lines. This turned into a media frenzy against high voltage alternating current and the seemingly greedy and callous lighting companies that used it.[78][79] Edison took advantage of the public perception of AC as dangerous, and joined with self-styled New York anti-AC crusader Harold P. Brown in a propaganda campaign, aiding Brown in the public electrocution of animals with AC, and supported legislation to control and severely limit AC installations and voltages (to the point of making it an ineffective power delivery system) in what was now being referred to as a "war of the currents".[80] The development of the electric chair was used in an attempt to portray AC as having a greater lethal potential than DC and smear Westinghouse, via Edison colluding with Brown and Westinghouse's chief AC rival, the Thomson-Houston Electric Company, to ensure the first electric chair was powered by a Westinghouse AC generator.[81]

Edison was becoming marginalized in his own company having lost majority control in the 1889 merger that formed Edison General Electric.[82] In 1890 he told president Henry Villard he thought it was time to retire from the lighting business and moved on to an iron ore refining project that preoccupied his time.[77]: 28–29 Edison's dogmatic anti-AC values were no longer controlling the company. By 1889 Edison's Electric's own subsidiaries were lobbying to add AC power transmission to their systems and in October 1890 Edison Machine Works began developing AC-based equipment.

Cut-throat competition and patent battles were bleeding off cash in the competing companies and the idea of a merger was being put forward in financial circles.[77]: 56–57 With the Edison company winning its electric lamp patent infringement cases, Villard began to float the idea of acquiring one of Edison's AC rivals, thereby eliminating many of the further costly patent case and gaining control of that companies AC patents.[77]: 56–58 In 1892 Villard teamed up with J. P. Morgan to engineer a merger of Edison General Electric with its main alternating current based rival, The Thomson-Houston Company. For Villiard and Edison General Electric the plan backfired. Morgan decided Thomson-Houston was the more valuable of the two companies, ousted Villiard, and put the Thomson-Houston board in charge of the new company, now called General Electric.[83][77]: 56–58 [82] General Electric now controlled three-quarters of the US electrical business and would compete with Westinghouse for the AC market.[84][77]: 28–29

Edison put on a brave face, noting to the media how his stock had gained value in the deal, but privately he was bitter that his company and all of his patents had been turned over to the competition.[85] He served as a figurehead on the company's board of directors for a few years before selling his shares.[86][87]

Remove ads

Mining

Summarize

Perspective

Starting in the late 1870s, Edison became interested and involved with mining. High-grade iron ore was scarce on the east coast which resulted in high costs as ore was shipped usually from the Midwest. He tried to change this by mining low-grade ore and beach sand.[88] Several others had attempted to improve the refining process by using magnets to separate iron from other metals, but none had been able to do so profitably.[8]: 283

The Edison Ore Milling Company began in 1880 with separating iron out of beach sand. Edison made promises to deliver hundreds of tons of ore a month to several customers, but after three years the operation was shut down and only one customer had received their ore. William Kennedy Dickson and John Birkinbine helped lead the venture.[88] Batchelor and Insull provided some of the capital with Edison taking the majority share financed from his own pocket.[8]: 282

Rather than a complete loss, this first mining venture allowed Edison to license some of the technology to more profitable iron producers. The West Orange team continued to iterate on the technology for years and Edison purchased a mine in Bechtelsville, Pennsylvania.[88] Birkinbine wanted to use this as a demonstration mine to sell the technology to mine owners, but Edison wanted to take over the mining industry himself. Birkinbine was fired in 1890.[89]

Edison bought several mines in the eastern states and began constructing a new centralized mining operation in Ogdensburg, New Jersey. The new process used rollers and crushers that pulverized five ton rocks.[90] To obtain the boulders, Edison purchased the largest steam shovel in America.[8][90] One novelty of Edison's system was the electrically powered seventy ton rollers which were rotated 3500 ft/min. To protect the system, the roller's gears released at the moment the boulders were dropped in and their momentum crushed the rocks.[8][90] Edison departed from contemporary, manually intensive, mining practices by prioritized automation.[8][90] This meant the rocks journeyed up, down, and across the facility on conveyor belts utilizing gravity, sieves, and additional rollers to separate ore in fines.[8][90] The fines were recirculated through a magnetic gradient created by an array of four hundred eighty electromagnets to select for iron.[90]

Customers would not accept iron with a significant phosphorus content because it ruined the Bessemer process. Edison's system removed the phosphorus with a light pneumatic system that leveraged phosphorus' lower density.[90] Economic forces also dictated that the iron ore be mixed into briquettes for transport and handling at steel mills. Edison advanced the automation of this process and was proud of it taking two hours. The eventual goal was for no humans to touch the iron.[91] Nevertheless, the mine was rapidly losing money.[90]

In 1893, the United States was in a severe recession. Between the capital investments in mining, falling iron prices, and the expensive lifestyle of Mina and his children Edison was at risk of becoming insolvent. He was also unwell as his diabetes was beginning to effect him.[8]: 314 He decided to take a loan from his father in law.[92][8]: 352–354

In 1901, Edison visited an industrial exhibition in the Sudbury area in Ontario, Canada, and thought nickel and cobalt deposits there could be used in his production of electrical equipment. He returned as a mining prospector and is credited with the original discovery of the Falconbridge ore body. His attempts to mine the ore body were not successful, and he abandoned his mining claim in 1903.[93]

Cement

Despite the failure of his mining company, Edison used some of the materials and equipment to produce Portland cement.[94][95] Manufacturing of iron ore produced a large quantity of waste sand which Edison sold to cement manufacturers. In 1899, he established the Edison Portland Cement Company, intending to manufacture his own cement and make improvements to its production process.[96]

In the manufacturing of Portland cement, limestone, the primary ingredient, is baked at high temperature with the other minerals. Edison designed a novel system which improved the efficiency of this process by baking the cement in horizontal 150ft long kilns which allowed the cement to achieve the same quality after cooking longer at a lower temperature. This consumed less coal resulting in saving from the manual labor needed to load coal into kilns. Edison reused most of the factory material from the iron extraction process at the Ogden mine to construct his new system. In addition to selling the cement itself, Edison later licensed the proven system to cement manufactures in America and collected royalties into the 1920s.[95]

Running machines in the dusty environment natural to crushing rocks yielded many problems for the machines. Dynamos in particular were problematic because they could not be sealed off due to heat dissipation. Edison invented a fan cooling system to bring in fresh air to cool the dynamos while sealing them off from the dusty factory air.[97]

In 1901, Edison sought to parlay his cement business by starting a cheap housing development initiative. He wanted to create small towns in which every American could afford to buy a home. To bring down the cost of building he commissioned a system for casting a whole three story house from cement in a single mold. He used this method to build employee housing and made a public relations campaign that did not yield sufficient demand for him to pursue it further.[98]

Remove ads

West Orange

Summarize

Perspective

Moving the works

The first labor strike against Edison occurred in the spring of 1886. It was led by D.J. O'Dare of the Edison Tube Works. Manufacturing in New York City was typically performed for nine hours a day, and Edison's employees were among the best paid in the city. However, they were not paid overtime for the additional work that was often performed. The strike sought more pay, overtime pay, and the right to unionize work. Edison and other managers were completely unwilling to negotiate unionization due to the loss of control. By the end of the year, the various manufacturing facilities in the city were closed and centralized as the Edison United Manufacturing Company opened a new factory in Schenectady, New York. The citizen's of Schenectady subsidized 16% of the real estate cost to help attract Edison's business to their town.[99]

Samuel Insull began working for Edison in 1881 as a secretary. He had previously worked at Vanity Fair. The two became friends as Insull became a trusted lieutenant. Later, when Mary was dying, Insull helped the family make arrangements. As with all of Edison's men, Insull worked hard. When Edison United Manufacturing Company opened, he was one of two managers.[100]

In December, Edison was housebound due to pleurisy. He recovered, but by May 1887 he needed emergency surgery to treat abscesses below his ear.[101] He had surgeries there again in 1906 and 1908.[11]: 422

By 1887, Edison felt he had outgrown Menlo Park. He put Batchelor in charge of constructing a new laboratory complex in West Orange, which when finally constructed was more than ten times the size of the old lab.[102]

In December 1914, a fire killed one employee and destroyed thirteen buildings causing $1.5 million in damages.[11]: 432 [8]: 168 The phonograph works was destroyed. Edison was optimistic about the situation, ordered everything rebuilt with the newest technology and was manufacturing records again by January.[103][11]: 432 The impact of the fire was partially mitigated because the factory practiced regular fire drills.[8]: 168

In 1921, following the inauguration of Warren G. Harding, the American economy was entering a recession. At this point, Edison had experience leading his businesses through recessions and had seen several of his friends go bankrupt when they were unable to manage. He fired thousands of his employees including executives. By the fall, the economy recovered, and business returned; however, it was a near miss with bankruptcy.[8]: 29–36

Fluoroscopy

Edison learned about X-rays in 1896, following their discovery by Wilhelm Röntgen. He was sent a photo of Röntgen's hands with the bones visible. The new technology excited Edison and he tried developing an X-ray system with better glass and more electric power than previously used. While experimenting, Edison learned X-ray images display better on calcium tungstate screens and informed Lord Kelvin.[104]

The fundamental design of Edison's fluoroscope is still in use today, although Edison abandoned the project after nearly losing his own eyesight and seriously injuring his assistants, Clarence Dally and Charles Dally.[11]: 422 [105] In 1903, a shaken Edison said: "Don't talk to me about X-rays, I am afraid of them."[106] The brothers often acted as human guinea pigs for the fluoroscopy project. Clarence died, at the age of 39, of injuries related to the exposure, including mediastinal cancer.[11]: 422 [105]

Rechargeable battery

In the late 1890s, Edison worked on developing a lighter, more efficient rechargeable battery. He saught something customers could use to power their phonographs, but in the early 1900s focused on batteries for electric cars. At the time, lead acid batteries were widely used, but not very efficient and protected by others' patents. In 1900, Edison decided to pursue an alkaline battery for electric cars.[107] His lab tested 10,000 combinations of electrodes and solutions eventually settling on a nickel-iron combination.

Waldemar Jungner simultaneously worked on a similar design which Edison likely knew about.[108][8]: 223, 224, 232 Edison and Junger litigated over their respective intellectual property as Edison attempted to commercialize his battery.[8]: 250, 251 Edison obtained a US and European patent for his nickel–iron battery in 1901 and founded the Edison Storage Battery Company.[108] In 1904, Edison was worried about losing the patent fight and personally petitioned president Theodore Roosevelt to step in. Roosevelt obliged; however, the patent office still denied Edison's claim.[8]: 253, 255

By 1904 Edison Storage Battery Company had 450 employees.[108] The first rechargeable batteries they produced were for electric cars.[108][109] A total recall was issued due to the batteries losing power after several recharge cycles.[108][8]: 256 When the capital of the company was exhausted, Edison paid for the company with his private money.

Henry Ford first met Edison, in 1896, while working for Edison Illuminating Company. Edison encouraged Ford's nascent automobile tinkering and Ford resigned in 1899 to start his first motor company.[110][111] By 1908, with the Model T on the road, gas cars were taking over the market.[112] Edison did not demonstrate a mature battery until 1910: a very efficient and durable nickel-iron-battery with lye as the electrolyte. The nickel–iron battery was never very successful; by the time it was ready, electric cars were disappearing, and lead acid batteries had become the standard for starting gas-powered cars.[108] Ford was still enamored with Edison and lent him $1.1 million ($34.5 million in 2024) to finance further battery research, but Edison was unable to bring a sufficient battery to market.[113]

Remove ads

Motion pictures

Summarize

Perspective

While working on the mining project, Edison and William Kennedy Dickson, one of his employees at the mine who was also a photographer, began trying to make camera "to do for the eye what the phonograph does for the ear".[114] Edison focused on the electromechanical elements while Dickson lead the optical and film effort.[11]: 294 Edison was granted a patent for a motion picture camera, labeled the "Kinetograph".[115] Much of the credit for the invention belongs to Dickson.[11]: 294

In fact, Edison's eye was trained on a bigger prize than a motion camera. He wanted a kinetophonograph to capture motion picture and record sounds with synchronized playback.[8]: 317 [11]: 296 In the spring of 1890, Dickson produced the first video with sound starring himself.[11]: 296 However, keeping the sound and video synchronized outside of a laboratory setting proved to be very difficult and Edison shelved commercial development of the technology.[8]: 135

In 1891, Thomas Edison built a Kinetoscope or peep-hole viewer. This device was installed in penny arcades, where people could watch short, simple films.[116] The kinetograph and kinetoscope were both first publicly exhibited May 20, 1891.[11]: 296

Edison and Dickson were preoccupied with the mining project and growing revenue from the phonograph business. This slowed the commercialization of Edison's motion picture camera and gave Dickson more time to iterate on the details. In 1894, they shifted from marketing campaigns to raise awareness to commercializing their inventions.[11]: 296–297

In the last three months of 1894, an associate of Edison's sold hundreds of kinetoscopes in the Netherlands and Italy. In Germany and in Austria-Hungary, the kinetoscope was introduced by the Deutsche-österreichische-Edison-Kinetoscop Gesellschaft, founded by the Ludwig Stollwerck[118] of the Schokoladen-Süsswarenfabrik Stollwerck & Co of Cologne.

By 1895, Dickson was beginning to set up business for himself separate from Edison. The exact motivation for the split is unknown but likely stemmed from disagreements between Dickson and Edison.[11]: 301 [119][120]

The first kinetoscopes arrived in Belgium at the Fairs in early 1895. The Edison's Kinétoscope Français, a Belgian company, was founded in Brussels on January 15, 1895, with the rights to sell the kinetoscopes in Monaco, France and the French colonies. The main investors in this company were Belgian industrialists. On May 14, 1895, the Edison's Kinétoscope Belge was founded in Brussels. Businessman Ladislas-Victor Lewitzki, living in London but active in Belgium and France, took the initiative in starting this business. He had contacts with Leon Gaumont and the American Mutoscope and Biograph Co. In 1898, he also became a shareholder of the Biograph and Mutoscope Company for France.[121]

In April 1896, Thomas Armat reached a deal with Edison in which Edison's company manufactured and sold the Vitascope to project films produced in Edison's film studio. Armat advertised as an Edison invention to boost sales, but was in fact, Armat's invention. Edison had made his own projector, but both men knew the Vitascope was better at the time.[122]

Edison's film studio made nearly 1,200 films. The majority of the productions were short films showing everything from acrobats to parades to fire calls including titles such as Fred Ott's Sneeze (1894), The Kiss (1896), The Great Train Robbery (1903), Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1910), and the first Frankenstein film (1910). Edison was happy to have Edwin S. Porter porter run the creative side of the movie business.[123] In 1903, the owners of Luna Park, Coney Island announced they would execute Topsy the elephant. Edison Manufacturing filmed, Electrocuting an Elephant, as AC current killed the poor animal.[8]: 243

As the film business expanded, competing exhibitors routinely copied and exhibited each other's films.[124] To better protect the copyrights on his films, Edison deposited prints of them on long strips of photographic paper with the U.S. copyright office. Many of these paper prints survived longer and in better condition than the actual films of that era.[125]

In 1908, Edison started the Motion Picture Patents Company, which was a conglomerate of nine major film studios (commonly known as the Edison Trust).

In 1913, movies used live actors and bands to add sound to the experience. However, Edison was again feeling confident in his kinetophone[126] technology to synchronize recorded sound and motion picture playback.[8]: 135 Simultaneously, Leon Gaumont was developing similar technology. Both their systems required a skilled projectionist who could adjust the video speed for the sound playback.[8]: 136–137

In 1914, Edison fired Porter for unclear reasons. The technical aspects of silent, black and white film were mostly solved and the storytelling did not capture the inventor's interest. The kinetophone was hard to sell due to the difficulty in operating it. Edison's movie business began to decline.[127]

Edison said his favorite movie was The Birth of a Nation. He thought that talkies had "spoiled everything" for him. "There isn't any good acting on the screen. They concentrate on the voice now and have forgotten how to act. I can sense it more than you because I am deaf."[128] His favorite stars were Mary Pickford and Clara Bow.[129]

Remove ads

National security

Summarize

Perspective

Due to the security concerns around World War I, Edison suggested forming a science and industry committee to provide advice and research to the US military, and he headed the Naval Consulting Board in 1915.[130][131] However, he attended few of the meetings due to his deafness. One of the board's main tasks was to prepare a site to conduct research for the navy. Edison wanted to locate the site far from Washington DC, as too many visits from bureaucrats would slow down the research. However, he was not listened to by the other board members and turned his focus to experiments in military technology.[8]: 179, 188–194

Submarines

At the start of the war, Edison attempted several methods for improving submarine detection which failed to gain adoption by the Navy.[61] He allowed Miller Hutchinson, to promote his battery technology as a safer solution to lead battery power on submarines. An American submarine crew had suffered serious injuries to due one such battery leaking sulfuric acid which mixed with seawater to produce chlorine gas inside the vessel. However, the nickle-iron batteries, used by Edison, leak hydrogen gas. This was not a problem on automobiles but confined in the submarine becomes explosive. In January 1916, while undergoing maintenance with the new Edison test battery there was a hydrogen explosion inside the USS E-2 which killed five men. Edison and Hutchinson defended their battery stating that the explosion was due to operator error. However, many naval officials blamed Edison and Hutchinson for overselling the battery. The event derailed sales of the battery but did not destroy Edison's good standing with the navy.[8]: 163, 165, 173, 180–184

Rubber

In 1915, the United States consumed 75% of the world's rubber and produced a negligible amount.[132] Edison, and many other businessmen, became concerned with America's reliance on foreign supply of rubber.[133] He saught a native supply of rubber.[133][8]: 40 Domestic fears were realized when the Stevenson Plan was introduced in 1921.[8]: 39 [134] The laboratory was funded by Edison, Ford, and Firestone with $75,000.[133]

Age did not make Edison any less familiar with the press. He used his 80th birthday to give tours of his experimental garden and promote his research into various domestic plants for producing rubber.[134]

After testing 17,000 plant samples, he eventually found an adequate source in the Goldenrod plant. Near the end of 1929, Edison announced Solidago leavenworthii, also known as Leavenworth's Goldenrod could be bred to give a 12% latex yield.[135] Edison employed systematic problem solving to rubber production. He rejected other plants based on combinations of their latex content, the extraction processes needed to get the latex from the plant, where the latex is found in the plants, growth speed, and ability to harvest the plant.[8]: 53–54

Chemicals

The phonograph business had led Edison to personally search for and hire several chemists to develop chemicals to coat records with that would prevent them from being worn down as they were played. Edison eventually licensed Condensite from another chemist which was formed from the condensation of phenol and formaldehyde. At the start of World War I, the American chemical industry was primitive: most chemicals were imported from Europe. The war resulted in a shortage of phenol which was used to make explosives and Aspirin.[136]

Edison responded by undertaking production of phenol at his Silver Lake facility using processes developed by his chemists.[137] He built two plants with a capacity of six tons of phenol per day. Production began the first week of September, one month after hostilities began in Europe. He built two plants to produce raw material benzene at Johnstown, Pennsylvania, and Bessemer, Alabama, replacing supplies previously from Germany. Edison manufactured aniline dyes, which previously had been supplied by the German dye trust. Other wartime products include xylene, p-phenylenediamine, shellac, and pyrax. Wartime shortages made these ventures profitable. In 1915, his production capacity was fully committed by midyear.[136] Edison preferred not to sell phenol for military uses. However, he sold his surplus to Bayer who exported it to Germany.[138][136][8]: 163

Remove ads

Final years

Summarize

Perspective

Henry Ford, the automobile magnate, later lived a few hundred feet away from Edison at his winter retreat in Fort Myers. They were friends until Edison's death. Edison and Ford undertook annual motor camping trips from 1914 to 1924. Harvey Firestone and naturalist John Burroughs also participated.[139] The trips functioned as a moving advertisement for Ford cars, Firestone tires, and whatever Edison had going on at the time. A team of reporters joined to ensure word spread.[140]

In 1926, at 79 years old, Edison handed over the presidency of Thomas A. Edison, Inc. to Charles.[8]: 56, 59

Edison was active in business right up to the end. Just months before his death, the Lackawanna Railroad inaugurated suburban electric train service from Hoboken to Montclair, Dover, and Gladstone, New Jersey. Electrical transmission for this service was by means of an overhead catenary system using direct current, which Edison had championed. Despite his frail condition, Edison was at the throttle of the first electric MU (Multiple-Unit) train to depart Lackawanna Terminal in Hoboken in September 1930, driving the train the first mile through Hoboken yard on its way to South Orange.[141]

Death

In the final years of his life, Edison continued to chew tobacco daily and his diabetes worsened.[142] Edison died on October 18, 1931, at Glenmont and was buried on the property.[143][144]

Edison's last breath is kept, as a momento, in a test tube at The Henry Ford museum near Detroit. Charles Edison had the test tube prepared and sent to Ford as a symbol of his father's love of chemistry and friendship with Ford.[145] A plaster death mask and casts of Edison's hands were also made.[146]

Domestic life

Summarize

Perspective

Mary

On December 25, 1871, at the age of 24, Edison married 16-year-old Mary Stilwell (1855–1884), whom he had met two months earlier; she was an employee at one of his shops. They had three children:

- Marion Estelle Edison (1873–1965), nicknamed "Dot"[29]

- Thomas Alva Edison Jr. (1876–1935), nicknamed "Dash"[147]

- William Leslie Edison (1878–1937) Inventor, graduate of the Sheffield Scientific School at Yale, 1900.[148]

Edison generally preferred spending time in the laboratory to being with his family.[31][29] He did not provide Mary much companionship and she was closest with her sister.[29]

Thomas Jr. was often sick as a child, but Edison left his care in Mary's hands. In her childhood, Marion often came to the laboratory at Menlo park.[149]

Wanting to be an inventor, but not having much of an aptitude for it, Thomas Jr. became a problem for his father and his father's business. Starting in the 1890s, Thomas Jr. became involved in snake oil products and shady and fraudulent enterprises, producing products being sold to the public as "The Latest Edison Discovery". The situation became so bad that Thomas Sr. had to take his son to court to stop the practices, finally agreeing to pay Thomas Jr. an allowance of $35 (equivalent to $1,225 in 2024)[150] per week, in exchange for not using the Edison name; the son began using aliases, such as Burton Willard. Thomas Jr. struggled with alcoholism and depression.[151] Thomas Jr. had a disastrous one year marriage which began in 1899 and caused scandal for himself and the senior Edison.[152] In 1931, nearing the end of his life, he obtained a role in the Edison company, thanks to the intervention of his half-brother Charles.[151]

When the Edisons moved to New York, they lived by Gramercy Park.[153] Edison neglected his wife after the first few years of their marriage.[154][11]: 123 [8] She enjoyed shopping for fashionable gowns, and attending balls.[8]: 433 By 1882, Mary's mental health was highly concerning to her doctor.[153]

Mary Edison died at age 29 on August 9, 1884, of unknown causes: possibly from a brain tumor[155] or a morphine overdose. Doctors frequently prescribed morphine to women at this time to treat a variety of causes, and researchers believe that her symptoms could have been from morphine poisoning.[156]

Mina

Thomas met Mina Miller at the World Cotton Centennial in December 1884. She was the daughter of the inventor Lewis Miller, who had made significant personal wealth by selling a wheat mower for which he had invented several improvements. He was a co-founder of the Chautauqua Institution, and a benefactor of Methodist charities.[157] Mina enjoyed the socialite lifestyle and practiced a strict Methodist faith her whole life.[8]: 106 She was a family friend of the Gillilands' and Edison met her several times in 1885 while working on a project with Ezra in Boston. He joined her for the Chautauqua gathering in 1885, but their flirting was dampened by the religious nature of the gathering. He proposed to her after the two took a trip in September.[158]

On February 24, 1886, at the age of 39, Edison married the 20-year-old Mina Miller (1865–1947) in Akron, Ohio.[159][160] They had three children:

- Madeleine Edison (1888–1979)[161][162]

- Charles Edison (1890–1969)[163]

- Theodore Miller Edison (1898–1992)[8]: 353, 633

Marion did not get along with Mina and moved to Germany in 1894.[164][8]: 323 She returned, in 1924, after divorcing her unfaithful husband.[165][8]: 55

According to Tesla:

If Edison had not married a woman of exceptional intelligence, who made it the one object of her life to preserve him, he would have died many years ago from consequences of sheer neglect.[166]

In his second marriage he was also often neglectful of his wife and children. When he was around, he was extremely controlling. He left nearly every aspect of housekeeping and child rearing to Mina and her five maids. One exception was the Fourth of July. Being deaf, Edison enjoyed the very loud boom made by fireworks. He made his own fireworks into which he added a small amount of TNT.[167]

Edison wrote Mina love letters about missing her while he was away for extended periods.[168][8]

Madeleine stated she had few childhood memories of her father, and he was typically only home once a week during her childhood.[169] She married John Eyre Sloane.[161][162]

Theodore was named after Mina's brother, who died in the Spanish-American War shortly before she gave birth. Her sister died in November of that year and her father died the following February 1899.[170]

Theodore went on to study physics at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).[8]: 20 After working for Charles while their father stepped down, Theodore decided to become an independent inventor running his own lab.[171]

Charles studied general science at MIT.[172] He took over his father's business after his death. Later he served one term as Governor of New Jersey (1941–1944).[163][8]: 633

Property

In 1885, Thomas Edison bought 13 acres of property in Fort Myers, Florida, for roughly $2,750 (equivalent to $96,240 in 2024) and built what was later called Seminole Lodge as a winter retreat.[173][174] The main house and guest house are representative of Italianate architecture and Queen Anne style architecture.[175]

Edison purchased a home known as Glenmont in 1886, in Llewellyn Park in West Orange, New Jersey.[176] He sold it to Mina in 1891.[177]

Edison liked boats, cars, and fishing.[178] He drove only on very limited occasions, but, for research purposes, owned several cars which helped him bond with his son, Charles, who he encouraged to drive even as a child.[179]

Remove ads

Views

Summarize

Perspective

On religion and metaphysics

Historian Paul Israel has characterized Edison as a "freethinker".[11] Edison was heavily influenced by Thomas Paine's The Age of Reason.[11] Edison defended Paine's "scientific deism", saying, "He has been called an atheist, but atheist he was not. Paine believed in a supreme intelligence, as representing the idea which other men often express by the name of deity."[11] In an October 2, 1910, interview Edison stated:

Nature is what we know. We do not know the gods of religions. And nature is not kind, or merciful, or loving. If God made me—the fabled God of the three qualities of which I spoke: mercy, kindness, love—He also made the fish I catch and eat. And where do His mercy, kindness, and love for that fish come in? No; nature made us—nature did it all—not the gods of the religions.[180]

Edison was labeled an atheist for those remarks, and although he did not allow himself to be drawn into the controversy publicly, he clarified himself in a private letter:

You have misunderstood the whole article, because you jumped to the conclusion that it denies the existence of God. There is no such denial, what you call God I call Nature, the Supreme intelligence that rules matter. All the article states is that it is doubtful in my opinion if our intelligence or soul or whatever one may call it lives hereafter as an entity or disperses back again from whence it came, scattered amongst the cells of which we are made.[11]

He also stated, "I do not believe in the God of the theologians; but that there is a Supreme Intelligence I do not doubt."[181]

Edison explored and promoted ideas in panpsychism.[182]

Politics

Republican

Edison's father was a Democrat that supported the secession of the Confederate States of America.[11]: 32–33 Edison was a lifelong Republican, but he briefly supported Theodore Roosevelt in his third attempt at the presidency as a Progressive party candidate.[8] He liked the Republican party's support of industrial capitalism and tariffs.[11]: 33

Presidents

Edison met several presidents. He met Rutherford B. Hayes in 1879 to demonstrate the phonograph. He met Benjamin Harrison in 1890. In 1921, Edison met Harding with the Firestone, Ford summer caravan. He met Calvin Coolidge in 1924 at the president's home in Vermont. In 1928, Edison received the Congressional Gold Medal and Coolidge called into the ceremony via radio. Herbert Hoover met Edison in 1929 at Seminole Lodge. Ten months later, Hoover traveled with Edison and Ford to Ford's reconstruction of Menlo Park.[183]

Suffrage

Edison was a supporter of women's suffrage.[184] He said in 1915, "Every woman in this country is going to have the vote."[184] Edison signed onto a statement supporting women's suffrage which was published to counter anti-suffragist literature spread by Senator James Edgar Martine.[185] His employment of women was somewhat notable at the time. He assigned women factory jobs that required nimble fingers like making the brush wires for dynamos.[186]

Pacifism

Nonviolence was key to Edison's political and moral views, and when asked to serve as a naval consultant for World War I, he specified he would work only on defensive weapons and later noted, "I am proud of the fact that I never invented weapons to kill." Following a tour of Europe in 1911, Edison spoke negatively about "the belligerent nationalism that he had sensed in every country he visited".[8]

Monetary policy

In May 1922, he published a proposal, A Proposed Amendment to the Federal Reserve Banking System.[187] Which proposes a commodity-backed currency. The proposals failed to find support and were abandoned.[188][189]

Remove ads

Awards

The following is an incomplete list of awards given to Edison during his lifetime:

- In 1878, honorary PhD from Union College[190]

- On November 10, 1881, Officer of the Legion of Honour[191]

- In 1892, Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society[192]

- In 1889, the John Scott Medal[191]

- In 1899, the Edward Longstreth Medal of The Franklin Institute[193]

- In 1908, John Fritz Medal[191]

- In 1915, Franklin Medal of The Franklin Institute[194]

- In 1920, the Navy Distinguished Service Medal.[191][195][8]: 21

- In 1923, the Edison Medal of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers[191]

- In 1927, the American Philosophical Society member[196]

- On May 29, 1928, the Congressional Gold Medal[191]

See also

- Edison Pioneers – a group formed in 1918 by employees and other associates of Thomas Edison

- Thomas Alva Edison Birthplace

- Thomas Edison in popular culture

- List of things named after Thomas Edison

References

Bibliography

Further reading

Primary sources

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads