Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Eichmann trial

1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

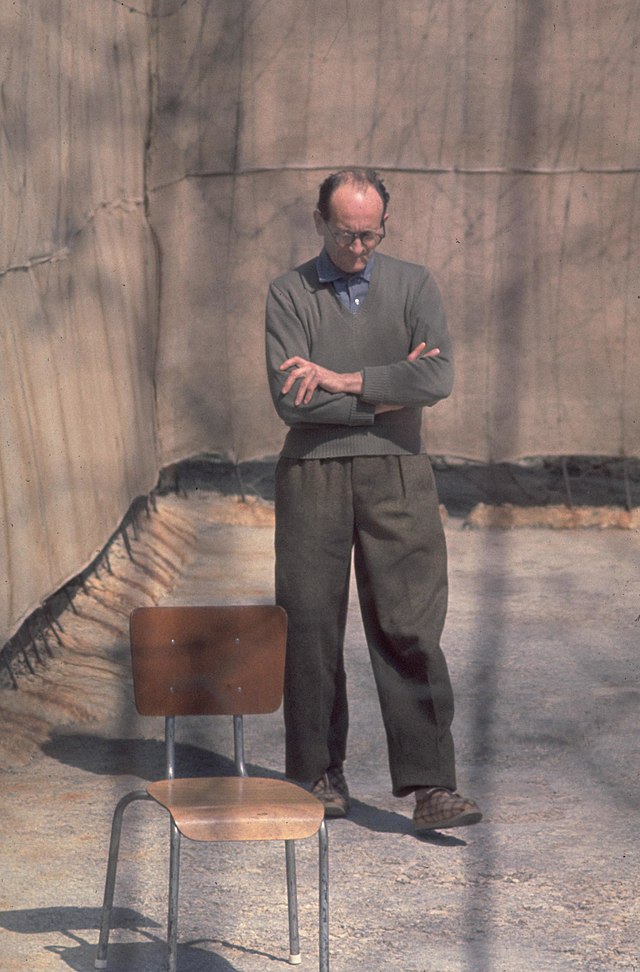

The Eichmann trial was the 1961 trial of major Holocaust perpetrator Adolf Eichmann who was captured in Argentina by Israeli agents and taken to Israel to stand trial. Eichmann was a senior Nazi party member and served at the rank of Obersturmbannführer in the SS, and was primarily responsible for the implementation of the Final Solution. He was responsible for shipping Jews and other people from across Europe to the concentration camps, including managing the shipments to Hungary directly, where 564,000 Jews died. After the end of World War II, he fled to Argentina, living under a pseudonym until his capture in 1960 by Mossad.

Eichmann was charged with fifteen counts of violating the Nazis and Nazi Collaborators (Punishment) Law.[1] His trial began on 11 April 1961 and was presided over by three judges: Moshe Landau, Benjamin Halevy, and Yitzhak Raveh. He was convicted on all fifteen counts and sentenced to death. He appealed his conviction to the Israeli Supreme Court, which confirmed the convictions and the sentence.

President Yitzhak Ben-Zvi rejected Eichmann's request to commute the sentence and he was hanged on 1 June 1962 at Ramla Prison.[2]

Remove ads

Background

Summarize

Perspective

Eichmann was a high-ranking SS official who played a key role in planning and executing the Holocaust. As head of Section IV-B-4 of the Reich Security Main Office (RHSA) under Reinhard Heydrich, Eichmann was in charge of Jewish affairs and deportations.[3] He organized the forced removal of hundreds of thousands of Jews from Germany and occupied parts of Europe, arranging transport trains to ghettos and extermination camps as part of the Final Solution.[3] Eichmann coordinated with other Nazi officials to ensure the systematic deportation and murder of Jews, and was deeply involved in operations such as the deportation of 440,000 Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz in 1944.[3]

Escape from Germany to Argentina

As the Second World War was ending in Europe, Eichmann fled as the Third Reich collapsed. He was captured by American forces in 1945, but managed to hide his identity using false papers and escaped from an American detention camp in 1946.[3] For several years he lived under aliases in Germany and avoided the trials associated with denazification. In 1950, with assistance from a network that helped fugitive Nazis, Eichmann secured an Argentine visa and a Red Cross passport under the name Ricardo Klement, fleeing Europe for South America.[3] Settling in Argentina, he was later joined by his wife and children and lived a low-profile life working various jobs, including at a Mercedes-Benz factory in Buenos Aires, all while concealing his true identity.[3][4] Among the German expatriate community, it eventually became an open secret that the individual known as Klement was in fact Eichmann.[4] During this period, he showed little to no remorse for his actions; he even gave interviews to pro-Nazi acquaintances, reportedly boasting that "not having murdered all the Jews" was his only regret.[4]

Meanwhile, an international manhunt was underway in Europe. Pursued persistently by war-crimes investigators and Nazi hunters like Simon Wiesenthal, Eichmann's name had surfaced during the Nuremberg trials but his whereabouts were unknown.[5] In the mid-1950s, clues and rumors suggested he was hiding in Argentina. In 1957, Fritz Bauer, the Attorney General of the German state of Hesse and himself a Jewish holocaust survivor, secretly informed Israeli agents that Eichmann was living in Buenos Aires under the name Ricardo Klement.[6] Bauer acted covertly due to fear that people in West Germany would potentially tip off Eichmann if official channels had been used instead.[6] His tip, corroborated by information from a German expatriate and Holocaust survivor in Argentina, gave Mossad critical leads that set them on Eichmann's trail.[6] Notably, it later emerged that the West German intelligence service (BND) and the Central Intelligence Agency had also learned his location by 1958, but chose not to pursue him or alert Israel.[7] Cold War considerations and the presence of ex-Nazis as informants contributed to their reluctance – an embarrassment that was acknowledged decades later when these facts came to light. Ultimately, it was the persistence of individuals like Bauer, Herrmann, and Wiesenthal, combined with Israel's resolve, that led to Eichmann's discovery.[6]

Remove ads

Abduction

Summarize

Perspective

Preparation

By 1960, Mossad had confirmation of Eichmann's whereabouts in the suburbs of Buenos Aires.[6] Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion, aware that formal extradition to Israel was unlikely (Argentina had a record of refusing to hand over Nazi fugitives) approved a covert operation to capture Eichmann.[3] In May 1960, a Mossad team led by agent Rafi Eitan and orchestrated by director Isser Harel set up surveillance and prepared an elaborate abduction plan.

Ten people were put to the task, including a disguise expert, a doctor, a document forger, a melee specialist and Harel himself. One of the agents was a survivor of Auschwitz where his parents were sent to the gas chamber. "We have not only the right, but also a moral duty to bring this man to justice [...] We are embarking on a historic journey. It goes without saying that this is no ordinary task. We must arrest the man who has the blood of our people on his hands," said Harel.[8]

The operation was top secret: Israel's embassy in Buenos Aires knew nothing and the mission was a violation of several UN conventions. For example, Argentina had to issue an extradition order before Eichmann could be taken out of the country. Using false passports, Mossad agents travelled to Buenos Aires in early 1960, and began an intensive and more than three-month long surveillance of Eichmann.[8]

The agents rented eight cars, as well as seven houses and apartments, which served as hiding places. One of the houses was isolated and served as headquarters. A few days after his arrival, this villa was transformed into a small fort with an alarm system and a cell where Eichmann was to be held captive until his departure for Israel.[8] A female Mossad agent stayed in the house the whole time disguised as a maid; her role was to cook for the group, keep the house clean and give the outside world the impression that a normal family lived there.[8]

The agents tracked down Eichmann's residence. On 19 March 1960, an agent drove slowly past the house, and at 2:00pm he saw a man in his fifties with a high forehead and glasses who was about to carry in the laundry. After Eichmann was identified, he was constantly shadowed and regularly photographed by Israeli agents.[8] The agents were regularly rotated so that Eichmann would not become suspicious. The agents charted Eichmann's habits: where he worked, when he showed up, when he went home for the day, and which bus he took to and from work.[8] Eichmann seemed like a normal family man, and lived according to fixed routines. He got off the bus every night at 7:40 p.m. and then walked along a deserted road to his house.[8]

Implementation

The plan was first to transport Eichmann out of the country by plane in connection with Argentina's national day, when Israeli diplomats were invited for an official visit. They were due to arrive on 19 May, and the plan was to return the plane on 20 May – without the diplomats, but with Eichmann on board. With the approval of the government of Israel, he was nevertheless captured on 11 May 1960.[8]

When Eichmann got off the bus in the evening, the agents had been feigning a breakdown. One of them signaled to Eichmann with the only Spanish phrase they knew: un momentito, señor, 'one moment, sir'.[9] Then, the agents took him by force into a waiting car.[8] During questioning, he immediately acknowledged who he really was.[10] While held prisoner, he wrote a declaration that he voluntarily joined Israel[clarification needed] and that he was willing to stand trial there.[6][11] Eitan told the BBC in 2011 that Eichmann was "completely average" in terms of physical description.[12]

The car with Eichmann went unnoticed through airport security. Eichmann was sedated and dressed in the uniform of Israel's flag carrier El Al. One member of the original flight crew remained in Buenos Aires so that the number of crew members would match, averting suspicion from the Argentinians. The Mossad agents gave the impression that Eichmann had been out drinking. After a layover in Dakar on the west coast of Africa, Eichmann arrived in Israel on 22 May.[13][11][14]

The Israeli government initially denied involvement in the abduction, claiming he had been taken by Jewish volunteers. On 23 May 1960, Ben Gurion announced in the Knesset that Eichmann had been captured with the government's blessing and described Eichmann as the greatest criminal of all time. He promised that the mass murderer would soon be brought to justice. Ben Gurion's announcement was followed by long and intense applause.[15][16]

Diplomatic reaction

When Ben-Gurion announced Eichmann's capture to the Knesset, the revelation stunned the world.[7] The Argentine government, angered that Israel had violated its sovereignty, lodged an official protest at the United Nations. A heated diplomatic dispute ensued in which Argentina demanded accountability for the act.[6] The Security Council debated the matter, and in June 1960 it adopted United Nations Security Council Resolution 138 acknowledging Argentina's grievance and requesting "Israel to make appropriate reparation". Ultimately, Israel and Argentina reached an agreement that Israel would express formal regret in exchange for Argentina not insisting on Eichmann's return.[6] By the time the trial commenced, the rift had largely been repaired quietly, and international focus shifted to the legal proceedings about to unfold in Israel.

Remove ads

Trial

Summarize

Perspective

The trial of Eichmann was held from 11 April to 15 August 1961 at Beit Ha'am, a community theatre temporarily reworked to serve as a courtroom capable of accommodating 750 observers.[17] It was held under the Nazis and Nazi Collaborators (Punishment) Law, legislation enacted to allow Israel to prosecute Holocaust perpetrators.[1] A special tribunal of the Jerusalem District Court was convened to handle the sensitive case.[18] The indictment, filed by Attorney General Gideon Hausner, charged Eichmann with 15 crimes, including crimes against the Jewish people, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and membership in outlawed organizations (the SS, SD, and Gestapo).[3] A summary of the charges and verdict can be found below.

Charges

Prosecution

The trial began on 11 April 1961, and was one of the first to be widely televised, bringing Nazi atrocities to a global audience.[3] A bulletproof glass booth was installed in the courtroom to shield Eichmann throughout the proceedings, both to prevent any revenge attack and to symbolically display him as a man in the dock separated from civil society.

At the beginning of the trial, the prosecution reviewed Eichmann's crimes. Hausner began (in Hebrew) with this opening statement:

In the place where I stand before you, Judges of Israel, to present the case against Adolf Eichmann, I do not stand alone. With me, at this moment, stand six million accusers. But they cannot rise to their feet, point an accusing finger towards the glass booth, and cry out towards the one sitting there – "I accuse." For their ashes are piled up on the hills of Auschwitz and the fields of Treblinka, washed away in the rivers of Poland, and their graves are scattered across Europe, from one end to the other. Their blood cries out, but their voices cannot be heard. Therefore, I will be their mouthpiece, and I will say on their behalf the terrible indictment.

— Gideon Hausner, Attorney General of Israel, from his opening statement[25]

The prosecution argued that Eichmann's role as a mid-level SS officer did not absolve him of personal responsibility — on the contrary, his bureaucratic authority made him directly culpable. Hausner emphasized that Eichmann was the genocide's executive arm, whose orders directly caused death.[26] Even if Eichmann did not personally kill the victims of the Holocaust, Hausner insisted that he should bear responsibility as if he had. This argument foreshadowed the modern concept of command responsibility; Eichmann's position heading the Gestapo's Jewish Affairs office meant that he coordinated the deportation and killing of Jews, and thus he was as culpable as the trigger-pullers. The court agreed.[27] Eichmann's defense of superior orders was legally invalid under the anti-Nazi law and principles from Nuremberg — superior orders could mitigate but not entirely excuse such crimes.[26] Hausner rejected the notion that Eichmann was a mere cog in the system, describing him as having zealously "planned, initiated, [and] organized]" the killing of the Jews.

The prosecution showed that Eichmann was a key coordinator in a systemic genocide, working with many others in the Nazi hierarchy. The court in its judgment formulated an innovative theory of liability, making clear that participation in a coordinated plan such as the Final Solution incurred full criminal responsibility.[28][27] Evidence showed[27] that he acted in concert with superiors like Himmler and Heydrich as well as subordinates across occupied Europe to carry out genocide. By linking Eichmann to this common design, the prosecution argued that there was shared intent and culpability for all crimes committed through the Nazi extermination apparatus.[27][28]

A core task for the prosecution was proving Eichmann's mens rea, that he knowingly and intentionally furthered the extermination of the Jews. They refuted Eichmann's claims of ignorance by highlighting his deep involvement in planning and executing it. For instance, during cross-examination Eichmann himself admitted that they discussed various ways to kill at the Wannsee Conference.[27] He saw mass murder with his own eyes during the war, eliminating any doubt that he knew what awaited the Jews after deportation. Prosecutors introduced Eichmann's own post-war boasts to demonstrate his genocidal intent and pride; in one instance, he proclaimed having "five million people on [his] conscience" as "a source of extraordinary satisfaction."[29] By documenting Eichmann's words and deeds, the prosecution established that he had specific intent on destroying the Jews. In his closing argument, Hausner underscored that Eichmann pursued the Final Solution fanatically and thoroughly.[26]

Goal to educate the public

The prosecution also aimed to educate Israel and the world about what had happened. Unlike the Nuremberg trials, which relied heavily on documents, the Eichmann trial put Holocaust survivors on the world stage.[3] This had a powerful didactic impact; night after night, the public heard firsthand accounts of atrocity on the witness stand, something which had never been so extensively broadcast before. Hausner explicitly stated that the trial should illuminate this for the younger generation.[30] He saw the courtroom as a forum to make sure the genocide of the Jews would be both historically recorded and legally addressed. Efforts were made to tie each narrative segment back to Eichmann. In practice, this meant that after a witness described a massacre or deportation, the prosecution would often introduce a related exhibit or testimony linking Eichmann to that event. By weaving the stories of survivors together with Nazi documents and Eichmann's own reports, the prosecution built a robust case that was also a chronicle on the Holocaust. This approach was specifically meant to both give a voice to the victims and educate the public without straying beyond the contents of the indictment.[27][18] The trial, widely televised, brought Nazi atrocities to a worldwide audience and "awakened public interest in the Holocaust" on an unprecedented scale.[3]

Witnesses

A hallmark of the prosecution's case was the extensive use of survivor testimony. Over a hundred witnesses were called to both establish Eichmann's personal contributions to the Holocaust and to paint a human picture of its scale.[18] Most of these witnesses had no direct encounters with Eichmann but were instead chosen to represent different types of Jewish experiences under the Nazis. Crucially, witnesses from across Europe were chosen so as to demonstrate the scale of the genocide. For example, Abraham Lewenson, a survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto, described conditions there and set the stage for later evidence about deportations. This strategy of presenting witnesses country by country meant the court heard about the Holocaust in a personal register before seeing how Eichman orchestrated the process on paper.

Among the most prominent witnesses was Zivia Lubetkin, a leader of the Jewish Combat Organization in Warsaw. She recounted the persecution of Warsaw's Jews and the uprising in 1943.[31] She described the starvation, deportations and finally the armed revolt in the ghetto. While her story did not mention Eichmann by name, it did reinforce the narrative of Nazi cruelty and Jewish resistance that the prosecution wanted the world to hear. It also countered any insinuation that Jews went "like sheep to slaughter." Her testimony generated interest in the theme of Jewish resistance in German-occupied Europe[3] and showed that even amid despair, Jews still had the will to fight, implicitly underlining the brutality of an oppressor who drove them to such extremes.

Another impactful witness was Abba Kovner, a poet from Vilnius, modern-day Lithuania. Kovner had been one of the first to warn that Hitler planned to annihilate all of Europe's Jews. He testified on 4 May 1961, offering a vivid account of the Vilna Ghetto and the emergence of armed resistance.[3] He described how rumors of mass killings turned into a grim reality and how he aided the youth resistance movement; he urged his fellow Jews in an underground manifesto to not "go like sheep to the slaughter". His testimony was so passionate that at one point Judge Landau halted him for straying so far into a personal narrative of heroism without direct connection to Eichmann.[18] His words left a strong impression on the public and underscored the idea that some Jews had understood Nazi intentions early and tried to fight back. His testimony reinforced Eichmann's culpability by illustrating his overarching plan; like Lubetkin's, his testimony had educational value. It personalized the abstract charge of "crimes against the Jewish people" via the voice of a survivor-hero.

The prosecution also called witnesses who did have direct encounters with Eichmann. In 1944, during the deportation of Hungary's Jews, Eichmann was shown to have made an offer to the wife of Jewish rescue activist Joel Brand in which a million Jews would be spared in exchange for ten thousand trucks.[18] Her testimony placed him personally at the center of the genocide in Hungary and was crucial in linking him to it. Similarly, other witnesses like survivors Jankiel Wiernik and Yehiel De-Nur (who were interned at Treblinka and Auschwitz respectively) gave harrowing descriptions of the camps, which demonstrated that Eichmann's work in assembling transports led directly to the gas chambers. De-Nur's testimony was so overpowering that he collapsed in court,[18] a moment seared in public memory.

Documentary evidence

The prosecution's documentary case was thorough as well. Thousands of pages of Nazi correspondence, orders, telegrams, and more were submitted to definitively link Eichmann to each stage of the Final Solution. These exhibits let the prosecution pin Eichmann down in the Nazi hierarchy, proving he was not a scapegoat but an active organizer. Often, the testimony of a survivor was followed by a German document identifying Eichmann's unit as coordinating the event in question. The judges later commented on the amount of material that was presented in the form of documents and reports to supplement the oral testimony.[27]

One of the most damning documents was the minutes of the Wannsee Conference. Eichmann had served as recording secretary for this meeting. The prosecution introduced the Wannsee Protocol to demonstrate Eichmann's intimate involvement in the Nazi decision-making process at the highest level. The minutes, written in euphemistic bureaucratic language, recorded discussions of transporting Jews for forced labor and also indicated that 11 million Jews in Europe were targets for the Final Solution. The document critically indicated that Jews would be worked to death and that any survivors would be killed.[27] Thus, it was argued that the mass extermination of Jews was explicitly on the agenda, and that Eichmann knew and facilitated this. The Wannsee evidence achieved two goals for the prosecution: solidifying Eichmann's intent and establishing his authority as a Nazi. The judges would later underscore that from Wannsee onward, Eichmann was recognized as a central coordinator for Jewish deportations across occupied Europe.

There was also a wealth of day-to-day evidence showing his personal involvement in the general logistics and planning of the Holocaust, including directives on preventing Jews from transferring or hiding valuables before deportation, train schedules, and telegrams.[27] Many of these were initialed or referenced by Eichmann in some form, proving he micromanaged the timing and number of Jews to be transported to the camps. One striking piece of evidence was Eichmann's own report tallying the progress of the extermination effort. The prosecution submitted an SS statistical report which Eichmann had commissioned in early 1943 to calculate the number of Jews already killed or deported at the time.[28] This tied him to the mass murder in that he was so deeply involved that he compiled body counts, proving that he had knowledge of the scope of the Holocaust.

Defense

In the courtroom, Eichmann's demeanor was largely calm and bureaucratic. When he took the stand in his own defense, he portrayed himself as a mid-level functionary following orders.[32] He repeatedly claimed he was "merely a little cog in the machinery" of genocide, not a policymaker.[3] However, he did acknowledge organizing the transport of "millions of Jews to their deaths" but stated that he personally did not feel any guilt because he did not kill them with his own hands.[3] This defense echoed those that many Nazis used in Germany, but it would not sway the court. From the outset, Eichmann's defense – led by Robert Servatius – challenged the legal basis of the trial based on four theories:

- The defense claimed that the three judges on the panel, all Israeli Jews, could not be truly objective in this case. Because Eichmann was accused of crimes against the Jewish people, the defense suggested that Jewish judges might consciously or unconsciously favor the prosecution. In other words, the claim was that their personal identity and the nature of the offenses created a conflict of interest, denying Eichmann a fair trial.[33] The court rejected any suggestion that Jewish judges could not give Eichmann a fair trial. The judges acknowledged they were "flesh and blood" human beings with emotions, but emphasized that the rule of law demands that all judges set aside their personal feelings. The panel affirmed it would judge Eichmann solely on the evidence and the law.[27]

- The defense next contended that the court had no right to try Eichmann at all due to the fact that he had been brought to Israel by illegal means. The abduction from Argentina, they argued, violated international law and Argentine sovereignty.[33] Servatius argued that because the "extradition" was unlawful, the trial itself was null and void. The court, quoting British and American courts (in particular, the US Supreme Court), found that jurisdiction to try an accused defendant would only depend on the essence of the criminal law cited in the indictment and its applicability to the charges in question, writing: "The uniform rule is that the court will not enter into an examination of this question which is not relevant to the trial of the accused. The ratio of this ruling is that the right to plead violation of the sovereignty of a state is the exclusive right of that state."[27][33]

- The third objection raised by the defense focused on the legal basis of the charges themselves. Eichmann was prosecuted under the Nazis and Nazi Collaborators (Punishment) Law[1] which was enacted by Israel in 1950, though his alleged crimes actually happened between 1939 and 1945, before Israel existed. Servatius argued that this was an impermissible ex post facto law, violating the fundamental legal principle nullum crimen sine lege, nulla poena sine lege ("no crime or punishment without law"). Eichmann's lawyer characterized the 1950 statute as creating new offenses after the fact.[33] The court did concede that non-retroactivity is a general principle of justice, but rejected its applicability for Eichmann's case. The judges found that the 1950 law did not, in fact, invent new crimes or punish innocent acts; instead, they argued, it merely provided a mechanism to punish acts that were universally condemned as criminal when Eichmann committed them.[33][27] The genocide of the Jews and other related atrocities had already been illegal under the standards of existing international law (including the laws of war) at the time. The fact that Nazi Germany did not enforce – and actively broke – those laws did not make the acts lawful. The law, they added, "did not introduce new legal norms; all it did was to make it possible to bring persons to trial for committing offenses that were known to be against the law at the time they were committed, in every place in the world, including Germany — the illegality of which these persons were well aware.".[27] In other words, Eichmann knew the acts were unlawful and decided to do them anyway, so he can be tried for them.

- Finally, the defense objected that Israel had no territorial or national jurisdiction over crimes committed in Europe years before Israel became a state. Eichmann was not an Israeli citizen, and neither were his victims, since Israel did not exist as a country at the time. The defense argued that under normal principles, a state's criminal law does not apply beyond its borders or to acts committed before the state's existence. Servatius contended that allowing Israel to try Eichmann for crimes in foreign lands was an unwarranted stretch of Israeli jurisdiction, contrary to the sovereignty of the countries where the crimes actually occurred.[33] The court addressed this on several grounds:

- First, the court invoked the doctrine of universal jurisdiction for extraordinary crimes under international law. The judges noted that certain offenses — in particular piracy, war crimes, and crimes against humanity — are so horrible and universally reprehensible that any country may prosecute them regardless of location or nationality. In support of this, they cited the view of the United Nations War Crimes Commission that "every independent state has, under international law, jurisdiction to punish not only pirates but also war criminals in its custody, regardless of the nationality of the victim or of the place where the offence was committed," especially when the crime would otherwise go unpunished.[27] In effect, this meant that every nation had the right to prosecute crimes like these.

- Secondly, the court also found that Israel had a unique connection to the crimes because they were directed against the Jewish people. The State of Israel was described not as just any state, but as a state "of the Jewish people," the same people who the Nazis tried to exterminate.[27] The judges elaborated that the Final Solution aimed to wipe out Jews everywhere, including those of Palestine who would later become Israelis. The court said rejecting Israel's link to the Holocaust would be like "cutting away the roots and branches of a tree and saying to its trunk: I have not hurt you".[27] Historically, the genocide of the Jews of Europe was one of the most direct causes for the establishment of Israel in 1948.[27] The court legally based this on the protective principle of jurisdiction, a state's right to punish offenses that threaten its fundamental interests. It also pointed out the inconsistency in the defense's argument: numerous countries (they counted eighteen) could each claim territorial jurisdiction for the murders of their own Jewish citizens, and Eichmann would accept those countries' right to try him — yet by the defense logic, Israel, as the state of the Jewish people, would uniquely lack jurisdiction since the murders did not physically happen there.[27]

- Finally, the court dismissed the notion that Israel's non-existence during World War II made any legal difference whatsoever. It cited a precedent (Katz v. Attorney General, a decision from an Israeli appellate court) which held that even if a state or court did not exist at the time of an alleged offense, it may still adjudicate the offense later as long as there is continuity in the legal authority to do so.[27] For example, many countries in Europe that were founded after the war tried crimes committed before their creation. The court applied the same logic in this case; it observed that the group of people against whom Eichmann's crimes were committed was now represented by the Israeli government, and it saw no logical or legal reason to bar the government from seeking punishment. In short, the court held that it had both the international law jurisdiction and the moral-historical jurisdiction to judge Eichmann's crimes.[27][33]

Nazi defense witnesses who refused to come to Israel for fear of being prosecuted testified before German courts according to questions sent by the Israeli court.[34][35] Throughout the trial, Eichmann, seated inside the glass booth, often took notes impassively, insisting the atrocities described were orchestrated by others above him in the Nazi hierarchy.[32][36]

Verdict

After months of proceedings, the trial concluded on 14 August 1961. On 11 December 1961, the three-judge panel delivered its verdict. Eichmann was found guilty on counts 1–12; he was only partially convicted on counts 13–15 due to the statute of limitations having expired for some (but not all) of his crimes.[32][36] The judges firmly rejected Eichmann's defense, ruling that he had been a key perpetrator, "not a puppet in the hands of others," but someone who "pulled the strings" of the genocide.[32] In an opinion totaling over 100,000 words in length, the judges described Eichmann's zealous implementation of the Final Solution and devotion to Nazi ideology.[32] They stated that delivering victims to their killers was as culpable as if Eichmann had actually killed them himself. They also dismissed his statement that he was only following orders, emphasizing that following obviously criminal orders could not absolve an individual of guilt.[32]

Remove ads

Sentence

Summarize

Perspective

On 15 December 1961, the court announced that Eichmann had been sentenced to death via hanging.[3] Eichmann was notably composed upon hearing the verdict and sentence. According to contemporaneous reports, he stood stiffly in his glass cage as the sentence was read, showing little emotion.[32] Per Israeli procedure, the verdict was subject to appeal and review. Eichmann's defense appealed to the Israeli Supreme Court in 1962, reiterating the arguments of illegal capture, jurisdiction, and claiming the trial judges erred in law and fact. The Supreme Court upheld the conviction on 29 May 1962, affirming that the trial had been fair and the verdict had been just. That same day, Eichmann penned a handwritten plea for clemency to Israeli President Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, writing that he was "a mere instrument in the hands of the leaders" and not a principal perpetrator. He added that he does not feel guilty for the events of the Holocaust because he was "not a responsible leader", adding that he detested the crimes that had been committed against the Jews and insisting that he had never been a fanatical anti-Semite.[37][38] His wife and brothers also sent appeals for mercy, asking that his life be spared on humanitarian grounds.[37]

The Israeli government gave the request serious consideration. A special cabinet meeting was called on 29 May 1962, to debate whether executing Eichmann was necessary or if commuting his sentence might better serve justice. A few prominent voices both inside and outside Israel advocated against hanging him. For example, philosopher Martin Buber urged clemency to avoid making Eichmann a martyr for neo-Nazis.[39] Despite this argument and others like it, the consensus firmly favored carrying out the death sentence. The Israeli cabinet ultimately voted unanimously to reject Eichmann's petition, with President Ben-Zvi concurring and responding that there was "no justification" to pardon Eichmann or mitigate the punishment.[39]

Early on 31 May 1962, Adolf Eichmann was executed by hanging at Ramla Prison. He reportedly uttered final words declaring his loyalty to Germany, Austria, and Argentina, right before the trapdoor opened. After the execution, Eichmann's body was cremated and his ashes scattered at sea, outside Israel's territorial waters,[3][40] to prevent any grave or memorial.

Shalom Nagar, the prison guard who was chosen to hang Eichmann, said that he did not volunteer for the task and had nightmares about it for years afterwards. He was selected as a personal guard for Eichmann while Eichmann was awaiting his execution. His duties included making sure Eichmann's food was not poisoned. In interviews he explained that after the deed was done, he was ordered to load the corpse into an oven for cremation, but his hands were shaking and he needed help walking. For an indeterminate time afterwards he suffered from PTSD and nightmares surrounding the hanging. He later became religious and moved to the West Bank settlement of Kiryat Arba.[41][42] He died on 26 November 2024.[citation needed]

Remove ads

Reactions

Summarize

Perspective

International reactions to the verdict were largely supportive, viewing it as the fitting punishment for one of the Holocaust's chief architects. Jewish communities worldwide welcomed the verdict as long-overdue justice. Prominent newspapers of the time praised Israel for conducting a fair trial despite the immense emotional weight of the case, and noted that Eichmann's fate served as a warning to other war criminals.[citation needed] The West German government expressed satisfaction that a major Nazi criminal had been brought to justice (even though the trial also prompted West Germany to reflect on its own efforts to prosecute Nazis).

There were also voices of caution; some human rights observers and religious leaders who generally opposed the death penalty lamented the execution, worrying capital punishment could diminish the moral high ground established by the trial. Nevertheless, by and large the world saw the trial and execution as an affirmation that even years after World War II had ended, perpetrators of genocide would be held accountable for their actions.[citation needed] The trial's extensive publicity had a profound impact on public awareness of the Holocaust, thrusting the horrors of the Holocaust in full into the global consciousness in a way that earlier post-war trials had not.[3] American Jewish writer Harold Rosenberg accepted that the trial was an opportunity for this, but regretted that it also elevated Eichmann as a figure. He gave a stark warning that being put on trial gave Eichmann an opportunity to become a notable figure in history.[43][44]

In Israel, the trial and execution were met with a sense of grim satisfaction – a symbolic closing of a horrific chapter of history. Journalist and poet Haim Gouri said of the trial, "we shall have to listen to all the witnesses, every last one, in the days and weeks and months to come. There will be no escape and no reprieve. We wanted a trial, and we got one."[43][45] As Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion summarized, the importance of the Eichmann trial was not vengeance, but to teach the world about what had happened and as a measure of justice for the millions whose lives were lost.[46] Historian Tom Segev said that one of Ben-Gurion's goals in trying Eichmann was to "impress the lessons of the Holocaust on the people of Israel, especially the younger generation."[40]

Criticism

The trial generated significant scholarly and philosophical debate in the years that followed, with some critics scrutinizing the legal and ethical dimensions of the proceedings in Israel. The most famous critique came from political theorist Hannah Arendt, who covered the trial for The New Yorker and later published a book titled Eichmann in Jerusalem. In it, she coined the phrase "the banality of evil," portraying Eichmann not as a monstrous fanatic but as an ordinary bureaucrat who had simply abdicated his own moral judgment.[13][47] Observing Eichmann's persona in the glass booth, she was struck by his "terrifyingly normal" demeanor.[48] Arendt argued that Eichmann's thoughtless, routinized participation in evil was much more frightening than if he had been a psychopath. She also raised questions about the trial itself, criticizing the prosecution for focusing so heavily on telling the story of the Holocaust rather than strictly on Eichmann's individual crimes.[47] Additionally, Arendt's book controversially discussed the role of certain Jewish leaders during the Holocaust, suggesting their cooperation with Nazi directives had inadvertently aided the Final Solution.[49] This has been seen by some as victim blaming.[47]

Remove ads

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads