Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Endometriosis

Disease of the female reproductive system From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

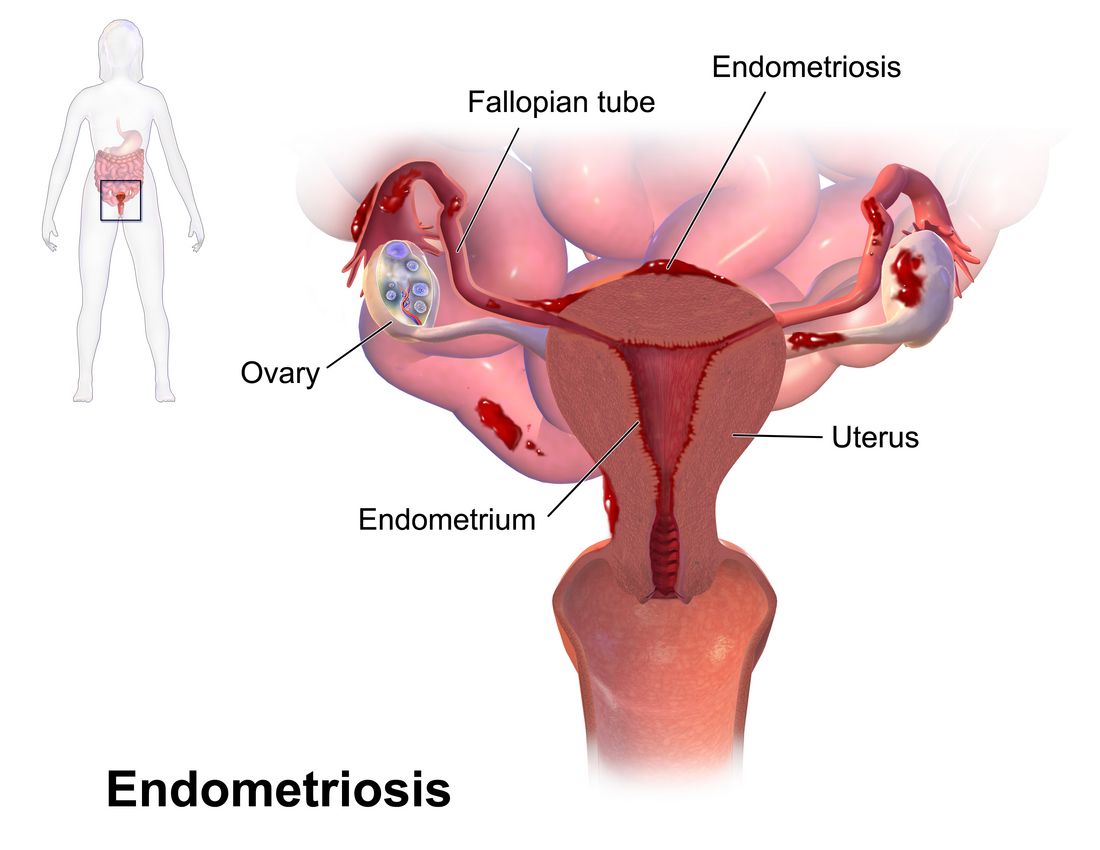

Endometriosis is a disease in which tissue similar to the lining of the uterus grows elsewhere in the body. It occurs in humans and a limited number of other mammals that have a menstruation cycle, notably primates. The tissue most often grows on or around the ovaries and fallopian tubes, on the outside surface of the uterus, or the tissues surrounding the uterus and the ovaries. It can also appear on the bowel, or bladder, or, rarely, on the lungs and skin.

Symptoms can be very different from person to person, varying in range and intensity. Some have no symptoms, while for others it can be a debilitating disease. Common symptoms include pelvic pain, heavy and painful periods, pain with bowel movements, painful urination, pain during sexual intercourse, and infertility. Besides physical symptoms, endometriosis can affect a person's mental health and social life.

Diagnosis is usually based on symptoms and medical imaging; however, a definitive diagnosis is made through laparoscopy (keyhole surgery). Other causes of similar symptoms include adenomyosis, uterine fibroids, irritable bowel syndrome, interstitial cystitis. Endometriosis is often misdiagnosed and many patients report being incorrectly told their symptoms are trivial or normal. It usually takes between 5 to 12 years after symptom onset before diagnosis.

Worldwide, around 10% of the female population of reproductive age (190 million women) are affected by endometriosis. Asian women are more likely than White people women to be diagnosed with endometriosis. The exact cause of endometriosis is not known. Possible causes include problems with menstrual period flow, genetic factors, hormones, and problems with the immune system.

While there is no cure for endometriosis, several treatments may improve symptoms. This includes pain medication, hormonal treatments or surgery. The recommended pain medication is usually a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), such as naproxen. Taking the birth control pill continuously or using a hormonal IUD (coil) is another first-line treatment. Other types of hormonal treatment can be tried if the pill or IUD are not effective. Surgical removal of endometriosis may be used to treat those whose symptoms are not manageable with other treatments, or to treat infertility.

Remove ads

Subtypes

Summarize

Perspective

Endometriosis can be subdivided into four categories:[4]

Superficial peritoneal endometriosis

- Small spots of endometriosis grow on the surface layer that covers the organs inside the abdomen or pelvis (the peritoneum)

Deep infiltrating endometriosis

- Lesions grow into the tissue beneath the lining of the pelvis or into the muscle layers of pelvic organs like the bowel, bladder, or ureter

Endometriomas (ovarian)

- Cysts that grow in the ovaries

Extrapelvic endometriosis

- Lesions outside of the pelvic regions, such as in the lungs or diaphragm

Health care providers may call areas of endometriosis by different names, such as implants, lesions, or nodules. Larger lesions may be seen within the ovaries as endometriomas or "chocolate cysts"; "chocolate" because they contain a thick brownish fluid, mostly old blood.[5]

Endometriosis most commonly affects the ovaries, the fallopian tubes between the ovaries and the uterus, the outer surface of the uterus and the tissues that hold the uterus in place. Less common pelvic sites are the rectum, bladder, bowel, vulva, vagina and cervix[6] Deep infiltrating endometriosis occurs when endometriosis grows more than 5 mm beneath the peritoneal surface.[7] It can infiltrate the muscles around organs.[4] The prevalence of deep infiltrating endometriosis is estimated to be 1–2% in women of reproductive age.[7] Deep endometriosis often looks like nodules, and can include fibrosis and adhesions.[4]

Rarely, endometriosis appears on the lungs, brain, and skin.[6] Diaphragmatic endometriosis forms almost always on the right hemidiaphragm, and may cause the cyclic pain of the right shoulder or neck during a menstrual period.[8] Scar endometriosis can rarely form on the abdominal wall as a complication of surgery, most often following a ceasarean section or other pelvic surgery.[9]

Remove ads

Signs and symptoms

Summarize

Perspective

Endometriosis is often associated with pain and infertility.[10] Some women with endometriosis do not have any symptoms, while for others the pain is life-altering. The amount of pain relates poorly to the anatomical extent of endometriosis. Those with 'minimal' endometriosis may have significant pain, while those with 'severe' endometriosis might have few symptoms.[11]

The most frequent symptom of endometriosis is pelvic pain, which includes:[10]

- Painful periods (dysmenorrhea) in 60% to 75% of people with endometriosis.[10] Severe period pain may interfere with daily activities.[12]

- Heavy menstrual bleeding.[12]

- Chronic pelvic pain that can interfere with school, work and social activities[10]

- Painful sexual intercourse (dyspareunia)[10]

- Painful urination or bowel movements, especially during periods.[10]

Women with endometriosis are about twice as likely to experience infertility compared to other women. Between 16% and 40% of women with endometriosis experience difficulty conceiving. In those going through assisted reproductive treatment, endometriosis is found in about 30% to 50% of women.[10] The World Health Organization estimates that endometriosis is the ultimate cause of female infertility in 4.8% of cases.[13]

Endometriosis can involve symptoms like constipation, diarrhea, nausea, bloating, rectal or abdominal pain. This is sometimes caused by endometriosis on the bowels, but often due to co-occuring irritable bowel syndrome. People with endometriosis often experience fatigue, which is linked to insomnia, depression and anxiety.[10]

Thoracic endometriosis occurs when endometrium-like tissue implants in the lungs or pleura around the lungs.[14] It is rare.[10] When it occurs in the lungs, common signs and symptoms are blood discharge from the lungs during menstruation and nodules which become bigger during menstruation. When it is found in the pleura, symptoms may be a collapsed lung during or outside of menstruation and bleeding into the pleural space. Further symptoms are a cyclical cough and cyclical shoulder pain. Most often, the endometriosis is found in the right lung.[14] Blood in urine may point to endometriosis in the bladder or in the ureter.[10] Sciatic endometriosis is a rare form in which endometrial tissue involves the sciatic nerve, causing cyclic nerve pain in the leg.[15]

Complications

Endometriosis may be associated with complications during pregnancy. Women with endometriosis have a three-fold increased risk of a placenta previa, in which the placenta partially or completely covers the cervical opening. Preterm delivery was almost 50% more likely. Other complications are stillbirth, gestational hypertension, pre-eclampsia, and placental abruption.[10]

Cardiovascular disease is also associated with endometriosis, in particular in those who have had a surgical removal of the uterus (hysterectomy) and ovaries. Cohort studies have found associations with strokes, heart attacks (myocardial infarction), high blood pressure and arrhythmia.[10] Endometriosis increases the risk of developing ovarian and thyroid cancers compared to women without the condition, and slightly increases the risk of breast cancer.[16]

Depression and anxiety are more common in endometriosis compared to healthy controls, but occur at the same rate as with other chronic pain conditions.[17] It is unclear how much this is caused by shared underlying mechanisms, the impact of severe symptoms, stigma, the related diagnostic delays or the ineffectiveness of treatment.[10]

Remove ads

Risk factors

Summarize

Perspective

Genetics

Inheritance is significant but not the sole risk factor for endometriosis. Studies attribute 50% of the risk to genetics, the other 50% to environmental factors.[18] Overall, 42 different loci (regions on a chromosome) have been associated with endometriosis risk. The genes linked to endometriosis risk help control cancer-related processes, sex-hormone signals, womb development, molecules related to inflammation and adhesions, and the growth of new blood vessels.[19]

There is significant overlap between the genetic basis of endometriosis, other pain conditions and inflammationary conditions. For instance, endometriosis shares a genetic underpinning with migraine and neck, shoulder and back pain. Among inflammatory conditions, it shares variants with asthma and osteoarthritis.[19]

Reproductive and environmental factors

Girls whose menstrual outflow is obstructed are at risk of developing endometriosis. This could be because of an imperforate hymen (a birth defect where the vagina is completely blocked), or a double uterus with a blocked hemivagina.[20] Other risk factors are having a first period before age 12, a menstrual cycle of fewer than 28 days, a low BMI, and not having had children.[4]

Little is known about environmental risk factors. Night work and red meat consumption seems to raise risk, as does exposure to some classes of environmental pollutants. The most studied of these are endocrine disruptors—chemicals that interfere with hormones, such as estrogen.[21] They include dioxins, phthalates, bisphenol A and polychlorinated biphenyl. Based on epidemiological and experimental data, it is possible exposure to some of them increases the risk of endometriosis.[21][22]

Autoimmune and autoinflammatory conditions

Endometriosis patients show a significantly increased risk of autoimmune, autoinflammatory, and mixed-pattern psoriatic diseases, with two studies in 2025 pointing to the connection. One of the studies suggested that the chances of receiving a diagnosis of at least one of the autoimmune conditions for those with endometriosis was around twice that of a control cohort. The linked conditions include rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, coeliac disease, osteoarthritis, and psoriasis. This reinforces the view that there is a genetic correlation between endometriosis and osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and multiple sclerosis (MS), and a potential causal link to rheumatoid arthritis. The work suggests a shared biological basis between endometriosis on one side, and autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases, on the other. This suggests that certain autoimmunne treatment pathways could be repurposed to provided alternative therapy options for those with endometriosis.[23][24]

Remove ads

Mechanism

Summarize

Perspective

Endometriosis is an inflammatory disease dependent on estrogen. The lesions promote local inflammation and immune system dysregulation. They also trigger the formation of adhesions (fibrous bands that form between tissues and organs) and fibrosis (excess connective tissue from healing). It is not well understood how endometriosis causes infertility and pain.[4]

Formation

Origin of endometriosis cells

The main theories for the formation of the endometrium-like tissue outside the womb are backward flow of menstrual blood, metastasis via the lymphatic or the circulatory system and local transformation of peritoneal cells into endometrial-like cells (coelomic metaplasia).[25]

During menstruation, some menstrual blood, tissue, and fluid can flow backward through the fallopian tubes into the pelvic area (the peritoneal cavity). This backward flow (called retrograde menstruation) is thought to be the main reason why endometriosis develops inside the pelvic cavity. However, this explanation alone is not enough, because almost all women have some backward flow of menstrual fluid, but only some of them develop endometriosis.[1]

Evidence supporting the theory comes from retrospective epidemiological studies and DNA analysis.[26][27] Furthermore, only animals with a menstrual cycle such as rhesus monkeys and baboons develop endometriosis. In contrast, animals like rodents and non-human primates with an estrous cycle in which the endometrium is reabsorbed rather than shed do not develop the disease.[26]

Endometriosis has been diagnosed in people who have never experienced menstruation including men, female fetuses, and prepubescent girls. One explanation for endometriosis in girls before puberty is coelomic metaplasia: the theory that certain cells in the peritoneum may undergo metaplasia (transformation) into endometrium-like cells. Müllerian remnants, cells that normally disappear during male embryonic development, may explain rare cases of endometriosis in men.[28] Metastasis via the lymphatic or the circulatory system may explain endometriosis outside of the pelvic region.[4]

Stem cells may contribute to the formation of endometriosis.[29] Stems cells in the basal layer of the endometrium play a role in renewing the tissue after menstruation. In women with endometriosis, more tissue is shed from this layer during menstruation, allowing more stem cells to flow back into the periteneum with retrograde menstruation, and form lesions.[30] Stem cells from bone marrow may drive the further growth of lesions, and also explain the establishment of endometriosis outside of the pelvic region.[11]

Other factors

Most women with retrograde menstruation do not develop endometriosis, so other factors are needed to explain the formation.[11] For endometriosis to develop, as is done by some cancerous tumors, its cells must evade the immune system, attach to a surface, and promote the formation of new blood vessels.[31] Endometriotic lesions differ in their biochemistry, hormonal response, immunology, and inflammatory response compared to the endometrium.[25]

Oestrogen is needed for the growth of endometriosis lesions. This is produced both by lesions locally and in other parts of the body.[25] Progesterone resistance in lesions make them less responsive to the hormone, and allows the lesions to grow outside of the womb.[32]

Immune dysfunction could be involved in the disease in various ways: it may lead to a decrease in clearance of endometrial cells outside the womb, a local inflammatory environment may make it more likely that the cells attach to a surface, and may reduce programmed cell death (apoptosis).[11]

Angiogenesis, the formation of new blood vessels, plays a key role in the maintenance of endometriotic lesions.[29] Gene expression around angiogenesis expressed in the endometrium of women with endometriosis are different from those without. In addition, cells in the periteneum of women with endometriosis release more growth factors that stimulate angiogenesis.[11]

Pain

There are multiple causes of pain. Endometriosis involves the formation of new blood vessels and nerves in a process known as neuroangiogenesis.[11] The inflammation and fibrosis around the lesions gives rise to nociceptive pain.[33] Neuropathic pain can arise from damage to nerves. In rare cases, endometriosis can infiltrate or compress nerves,[4] and damage to nerves might also occur due to surgery.[33] Estrogens can increase communication between immune cells and nerves in lesions, which may contribute to further pain.[11] Finally, there may be systemic (body-wide) inflammation, involving white blood cells. This can lead to nociplastic pain, which amplifies pain signals and reduces pain inhibition. Nociplastic pain also cause poor sleep, memory problems and fatigue.[4]

Infertility

The infertility associated with endometriosis likely has multiple causes. Inflammation and hormonal dysfunction explain some instances. The ovarian reserve, the amount of viable egg cells in the ovaries, is typically lower in those with endometriosis. In particular, endometriomas may reduce ovarian reserve in affected ovaries.[11] There is contradictory evidence on whether endometriosis causes reduced ovulation. Anatomical distortions, for instance from adhesions, can explain further instances of infertility, and in severe cases, sperm or egg cells may be fully blocked. Pain during sex may lead couples to avoid it, leading to fewer opportunities for natural conception.[34]

Remove ads

Diagnosis

Summarize

Perspective

A health history and a physical examination can lead the health care practitioner to suspect endometriosis. Symptoms in combination with ultrasound or MRI imaging can lead to a presumed diagnosis of endometriosis. The gold standard for definite diagnosis is via surgery and a biopsy, but there is a shift away from requiring surgical confirmation before starting treatment to prevent delays.[4]

Diagnosis takes an average of five to twelve years from the onset of symptoms.[4] This diagnostic delay has remained persistent. On average, it takes between one and four years before women seek medical help, which might be explained by the normalisation of symptoms, the lack of awareness, and lack of access to healthcare. It then takes up to nine years to get a diagnosis. This delay might be explained by a normalisation of symptoms, lack of expertise and tools, and general inefficiencies in healthcare.[35]

Endometriosis can be classified into four different stages. The American Society of Reproductive Medicine's scale, revised in 1996, gives higher scores to deep, thick lesions or intrusions on the ovaries and dense, enveloping adhesions on the ovaries or fallopian tubes.[36]

Physical examination

A trauma-informed framework is recommended for a physical examination, where the health practitioner validates pain and fosters trust. The examination focuses on assessing both general symptoms and those linked to deep endometriosis or endometriosis outside the pelvis. Risk factors are also reviewed. The physical examination can include an abdominal exam, a single digit exam of the vagina and pelvic floor, a bimanual exam and examination with a speculum.[4]

Ultrasound

Vaginal ultrasound can be used to diagnose endometriosis or to localize an endometrioma before surgery.[37] This can be used to identify the spread of disease in individuals with well-established clinical suspicion of endometriosis.[37] Vaginal ultrasound is inexpensive, easily accessible, has no contraindications, and requires no preparation.[37] By extending the ultrasound assessment into the posterior and anterior pelvic compartments, a sonographer can evaluate structural mobility and look for deep infiltrating endometriotic nodules.[38] Better sonographic detection of deep infiltrating endometriosis could reduce the number of diagnostic laparoscopies, as well as guide disease management and enhance patient quality of life.[38]

Ultrasounds cannot be used to exclude a diagnosis of endometriosis.[39] If a transvaginal ultrasound is not suitable or declined, an alternative is an ultrasound via the lower abdomen.[40]

Magnetic resonance imaging

MRI is another means of detecting lesions in a non-invasive manner.[41] MRI is not widely used due to its cost and limited availability.[41] It can reliably detect endometriomas and deep infiltrating endemetriosis. It is sometimes used for planning surgery, for instance if an ultrasound is unclear, or for diagnosis if a transvaginal ultrasound is not appropriate or is declined. The field of view is larger in an MRI compared to an ultrasound, which allows a larger part of the bowel to be assessed.[42]

Laparoscopy

Laparoscopy (keyhole surgery) is a surgical procedure where a camera is used to look inside the abdominal cavity. Laparoscopy with a biopsy is the most accurate way to diagnose endometriosis.[4] It can be used when endometriosis is suspected, but not visible via medical imaging.[11] An alternative after negative imaging is to try out treatment and give a presumed diagnosis if that improves symptoms ('empirical treatment').[43]

Surgery for diagnosis also allows for surgical treatment of endometriosis at the same time.[44] In nearly 40% of cases, no cause for pelvic pain is discovered during laparoscopy.[11]

The lesions of superficial endometriosis often appear dark blue or black. In the earlier stages of disease, they may be white, red or yellow-brown. Ovarian cysts are typically dark brown. Adhesions are made up of fibrous scar tissue. Deep endometriosis looks like multiple distinct nodules.[11]

A biopsy may be negative even when endometriosis is present, particularly in younger women. As such, it cannot be used to exclude a diagnosis of endometriosis.[11] For confirmation, biopsy samples should show at least two of the following features:[45]

- Endometrial type stroma

- Endometrial epithelium with glands

- Evidence of chronic hemorrhage, such as hemosiderin deposits

- Endometriosis, abdominal wall

- Micrograph showing endometriosis (right) and ovarian stroma (left)

- Micrograph of the wall of an endometrioma. All features of endometriosis are present (endometrial glands, endometrial stroma and hemosiderin-laden macrophages).

Stages

There are three staging or classification systems commonly used. Fertility is assessed with the Endometriosis Fertility Index (EFI).[11] Endometriosis can be classified as stage I–IV by the revised American Society of Reproductive Medicine (rASRM) staging system. The stages range from minimal (stage I) to severe (stage IV).[46] The scale uses a point system that assesses lesions and adhesions during surgery. The ENZIAN system focuses more on deep endometriosis compared to rASRM. The rASRM and ENZIAN systems correlate poorly with how much pain women have.[11]

The American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (AAGL) endometriosis staging system, introduced in 2021, was designed to correlate well with complexity of surgery. Like rASRM, it divides endometriosis into four stages.[28]

Differential diagnosis

Various conditions exhibit similar symptoms to endometriosis. Adenomyosis, the growth of endometrium-like tissue in the muscles of the uterus, is one example. It sometimes shows characteristics on an MRI that can distinguish it from endometriosis. Interstitial cystitis is mainly characterised by painful urination, but also cause more diffuse pain. It can be distinguished from endometriosis with a cystoscopy, which shows pinpoint hemorrhages in interstitial cystitis. Irritable bowel syndrome can sometimes be distinguished from endometriosis via the presence of diarrhea or constipation, and can be diagnosed in the absence of endometriosis via imaging or surgery.[47] Other conditions with overlapping symptoms are uterine fibroids, cervical stenosis and pelvic floor myofascial pain.[4]

Remove ads

Prevention

According to the World Health Organization, there is no known way to prevent endometriosis.[48] There are associations between some risk factors and endometriosis: women with endometriosis tend to consume more red meat, trans fats, alcohol and caffeine. Physical activity does not seem to prevent endometriosis, but can lessen pain. It is unclear whether these links are causative.[49]

Management

Summarize

Perspective

While there is no cure for endometriosis, there are treatments for pain and endometriosis-associated infertility. Pain can be treated with hormones, painkillers, or, in severe cases, surgery.[50] The goal of management is to provide pain relief, to restrict the progression of the process, and to restore or preserve fertility where needed.[25]

Treatment with medication for pain management can be initiated based on the presence of symptoms, examination, and ultrasound findings that rule out other potential causes.[51] The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends starting initial medication for those with suspected endometriosis, at the same time as referral for investigations such as ultrasound.[52]

In general, the diagnosis of endometriosis is confirmed during surgery, at which time removal can be performed. Further steps depend on circumstances: someone without infertility can manage symptoms with pain medication and hormonal medication that suppresses the natural cycle, while an infertile individual may be treated expectantly after surgery, with fertility medication, or with in vitro fertilisation (IVF).

Hormonal medications

Progestin-only hormonal suppression (progestogen) is another first-line therapy. It come in different forms and includes the hormonal coil (intrauterine device), the oral dienogest, an injection of medroxyprogesterone acetate every three months or an implant under the skin.[4] Dienogest, which may better than injections,[53] is not available on its own in the US.[4] Oral progestins likely reduce overall pain and period pain compared to placebo, and may also help with pelvic pain. It is unclear how well they work compared to other hormonal therapies.[53]

Hormonal birth control pills: combined estrogren-progestin birth control pills are a first-line treatment. The recommendation is to use the pills continuously to stop periods.[4] A 2018 Cochrane systematic review found that there is insufficient evidence to make a judgement on the effectiveness of the combined oral contraceptive pill compared with placebo or other medical treatment for managing pain associated with endometriosis partly because of lack of included studies for data analysis (only two for COCP vs placebo).[54]

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) modulators are second-line treatments: These drugs include GnRH agonists such as leuprorelin, and GnRH antagonists such as elagolix and decrease estrogen levels.[4] GnRH agonists mimic the effects of menopause, and seem more effective than placebo or oral progestin at reducing pain.[55] They come with side effects of hot flashes and decreased bone density. GnRHs can be prescribed with hormonal 'add-back' therapy or with calcium-regulating agents to reduce the amount of bone loss.[4][55]

Aromatase inhibitors are third-line treatments and block estrogen production throughout the body. Examples of aromatase inhibitors include anastrozole and letrozole. Common side effects are hot flashes, night sweats and functional cysts.[4][56] In premenopausal women, these should be taken with other hormones (such as the combined pill) to prevent ovarian stimulation and to prevent menopause symptoms. They can be a option for post-menopausal women who still have endometriosis symptoms, as their action is not limited to suppressing estrogen from ovaries. Evidence is limited.[4]

Progesterone receptor modulators like mifepristone and gestrinone have the potential (based on only one randomized controlled trial each) to be used as a treatment to manage pain caused by endometriosis.[57]

Pain medication

NSAIDs like naproxen are anti-inflammatory medications commonly used for endometriosis pain.[58] Evidence for their effectiveness is limited, with only one small study conducted. NSAIDs can have side effects, predominantly gastrointestinal, but they are generally safe to try.[59]

Surgery

Clinical guidelines recommend surgery when medical treatment does not work sufficiently, has unacceptable side effects or is contraindicated. Large endometriomas can only effectively be treated with surgery. Surgery is also recommended when deep endometriosis causes problems in the bowels or urinary tract, such as obstruction. It is unclear what the effect of surgery is for pain relief in cases of superficial periteneal endometriosis.[4]

Laparoscopy (keyhole surgery) is the standard surgical approach. Treatment consists of the removal of endometriosis and the restoration of pelvic anatomy via the division of adhesions.[60] The removal takes place via excision (cutting out) or electrosurgery (coagulation or ablation/vaporisation).[61][62] With laparoscopic surgery, small instruments are inserted through incisions to remove the endometriosis tissue and adhesions. After surgery, people can usually return home the same day.[63]

Two literature reviews have compared excision to ablation. A 2017 literature review found that excision improved some outcomes over ablation for endometriosis in general. A 2021 literature review on minimal to mild endometriosis found no difference. For deep endometriosis, excision is the standard therapy, as ablation does not allow the surgeon to see if all endometriosis is removed.[64] In the United States, some specialists trained in excision for endometriosis do not accept health insurance because insurance companies do not reimburse the higher costs of this procedure over ablation.[65]

Endometriomas are usually excised (removed completely). Compared to drainage and coagulation of the cyst, excision makes it less likely the cysts and pain symptoms come back. However, excision may damage fertility, as it can affect the ovarian reserve, the amount of egg cells that can be fertilised.[11][4]

For deep endometriosis, surgery improves quality of life and pain symptoms.[66] However, the procedure can be complicated, especially if the lesions are in or near the bowel, ureter of the urinary system or the chest, and requires a interdisciplinary surgical team in those cases. For instance, for rectovaginal endometriosis, 7% of surgeries had complications.[4] Sometimes, a part of the bowel or bladder is removed.[67][12]

For women who still have significant pain after hormonal treatment and other surgery, and do not want to become pregnant, a hysterectomy (removal of the womb) can be offered. This is done in combination with removal of endometriosis lesions. Removal of the womb may be beneficial if the uterus itself is affected by adenomyosis. When the ovaries are removed too, women will experience early menopause and may need hormone replacement therapy. Removal of the ovaries comes with cardiovascular, metabolic and mental health risks.[68][4]

Recurrence and postoperative hormonal suppression

In an analysis with a medium follow-up of 24 months pain after surgery recurred in about 16% of women.[4] Endometriosis recurrence following surgery is estimated as 21.5% at 2 years and 40–50% at 5 years. Hormonal therapy before surgery has little effect on recurrence, but treatment afterwards reduces the risk.[11] At a median follow-up of 18 months, endometriosis recurred in 26% of women without postoperative hormonal suppression, compared with 10% of women who received it.[4] The risk of recurrence is higher in younger women and in those with a less aggressive surgery.[62]

Comparison of interventions

A 2021 meta-analysis found that GnRH analogs and combined hormonal contraceptives were the best treatment for reducing dyspareunia and menstrual and non-menstrual pelvic pain.[69] A 2018 Swedish systematic review found several studies but a general lack of scientific evidence for most treatments.[37] There was only one study of sufficient quality and relevance comparing the effect of surgery and non-surgery.[70] Cohort studies indicate that surgery is effective in decreasing pain.[70] Most complications occurred in cases of low intestinal anastomosis, while the risk of fistula occurred in cases of combined abdominal or vaginal surgery, and urinary tract problems were common in intestinal surgery.[70] The evidence was found to be insufficient regarding surgical intervention.[70]

The advantages of physical therapy techniques are decreased cost, absence of major side effects, it does not interfere with fertility, and a near-universal increase in sexual function.[71] Disadvantages are that there are no large or long-term studies of its use for treating pain or infertility related to endometriosis.[71]

Treatment of infertility

Infertility can be treated with assistive reproductive technology (ART) such as in vitro fertilization (IVF) or surgery.[72] IVF procedures are effective in improving fertility in many individuals with endometriosis. IVF is increasingly recommended over surgery for older women or for those where there might be multiple reasons why they struggle to conceive.[73] It does not increase recurrence of endometriosis.[74] The Endometriosis Fertility Index can help guide decisions on treatment of infertility.[75] Surgery is typically not recommended before starting ART.[76]

In terms of surgery, endometriomas can be cut out (a cystectomy), or drained and destroyed (ablation). The ablation technique may be better able to preserve the number of remaining viable eggs (the ovarian reserve), compared to cutting out the endometrioma.[77] On the other hand, cutting out the endometrioma may help more with pain.[73] Surgery likely also helps with infertility in the case of superficial peritoneal endometriosis.[4] Receiving hormonal suppression therapy after surgery might be help with endometriosis recurrence and pregnancy.[78] but evidence for pregnancy outcomes is mixed[79] and the both NICE and the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology recommend against hormonal suppression to improve fertility.[79][80]

Remove ads

Prognosis

Endometriosis is often a long-term condition, with symptoms typically emerging during adolescence and easing after menopause. For some women, pain persists after menopause. Treatments, whether medical or surgical, can alleviate symptoms but do not provide a definitive cure.[81] The disease does not always worsen over time; in repeat surgeries, endometriosis became worse in 29%, improved in 42% and stayed the same in 29%.[11]

The likelihood of symptoms returning after surgery is highly variable, with studies reporting recurrence rates anywhere between 6% and 67%. For some, endometriosis becomes associated with persistent, complex pain, possibly linked to changes in the nervous system, as part of a constellation of chronic pain disorders.[81]

Remove ads

Epidemiology

Endometriosis is commonly reported to affect approximately 10% of women of reproductive age.[4] Worldwide, an estimated 176–190 million girls and women are affected,[82][83] with around 22 million having a diagnosis confirmed surgically as of 2021.[82] It is diffucult to determine an exact prevalence, given the large delays in diagnosis and the need for a surgical confirmation for a definite diagnosis.[83] The prevalence depends on the population studied and the way endometriosis is diagnosed (imaging, surgery). Of women with pelvic pain undergoing laparoscopy, 28% are diagnosed with endometriosis. Of those with infertility undergoing laparoscopy, 25% are diagnosed.[4]

It is most diagnosed when women are in their 30s, but symptoms typically start in early 20s or in adolescence.[4] People can develop endometriosis symptoms before their first period and in menopause too.[83] Ethnic differences in endometriosis have been observed. The condition is more common in women of East Asian and Southeast Asian descent than in White women.[25]

History

Summarize

Perspective

The earliest references to what is now known as endometriosis might be from Ancient Egypt, nearly 4,000 years ago.[84] In Ancient Greece, the Hippocratic Corpus outlines symptoms similar to endometriosis, including uterine ulcers, adhesions, and infertility.[85] Dioscorides, a prominent physician of the time, described 'strangulation of the uterus', associated with pelvic pain and sometimes leading to collapse.[84] He regarded menstrual pain as organic.[85] Women with dysmenorrhea were encouraged to marry and have children at a young age.[85]

During the Middle Ages, there was a shift into believing that women with pelvic pain were mad, immoral, imagining the pain, or simply misbehaving. The symptoms of inexplicable chronic pelvic pain were often attributed to imagined madness, female weakness, promiscuity, or hysteria.[85]

Endometriosis proper was first defined between the end of the 19th century and the start of the 20th. Some attribute the first description to Carl von Rokitansky in 1860, even though some authors consider it more likely he was describing malignent tissue.[86] Around 1896, Thomas Cullen and others described endometriosis and adenomyosis under the single name adenomyomas. Between 1903 and 1920, Cullen showed that the tissue in adenomyomas was endometrial.[87] John A. Sampson gave endometriosis its name.[88] He studied the pathogenesis of the disease and formulated the theory of retrograde menstruation as a cause of endometriosis.[88][89]

One early recommendation to prevent and treat endometriosis was pregnancy. For older women, another approach was surgery, involving oophorectomy (removal of the ovaries) and hysterectomy (removal of the uterus).[90] In the 1940s, the only available hormonal therapies for endometriosis were high-dose testosterone and high-dose estrogen therapy.[91] Success of high-dose estrogen therapy with diethylstilbestrol for endometriosis was first reported by Karnaky in 1948, but was associated with severe risks upon withdrawal.[90]

Pseudopregnancy (high-dose estrogen–progestogen therapy) for endometriosis was first described by Kistner and Andrews in the late 1950s, and become widely employed.[90] Danazol, was first described for endometriosis in 1971.[92] It was used for some 40 years, but had masculising side effects, including weight gain, excessive hair growth and breast atrophy.[93] In the 1980s, GnRH agonists gained prominence for the treatment of endometriosis and by the 1990s had become the most widely used therapy.[94] Oral GnRH antagonists such as elagolix were introduced for the treatment of endometriosis in 2018.[95]

Remove ads

Society and culture

Summarize

Perspective

Economic burden

The economic burden of endometriosis is widespread and multifaceted.[96] Endometriosis is a chronic disease that has direct and indirect costs, which include loss of work days, direct costs of treatment, symptom management, and treatment of other associated conditions such as depression or chronic pain.[96] One factor that seems to be associated with especially high costs is the delay between the onset of symptoms and diagnosis.

Costs vary greatly between countries.[97] Two factors that contribute to the economic burden include healthcare costs and losses in productivity. A Swedish study of 400 endometriosis patients found "Absence from work was reported by 32% of the women, while 36% reported reduced time at work because of endometriosis".[98] An additional cross sectional study with Puerto Rican women, "found that endometriosis-related and coexisting symptoms disrupted all aspects of women's daily lives, including physical limitations that affected doing household chores and paid employment. The majority of women (85%) experienced a decrease in the quality of their work; 20% reported being unable to work because of pain, and over two-thirds of the sample continued to work despite their pain."[99] A study published in the UK in 2025 found that after women received a diagnosis of endometriosis in an English NHS hospital their earnings were on average £56 per month less in the four to five years after diagnosis than they were in the two years before. There was also a reduction in the proportion of women in employment.[100]

Medical culture

There are many barriers that those affected face in receiving a diagnosis and treatment for endometriosis. Some of these include outdated standards for laparoscopic evaluation, stigma about discussing menstruation and sex, lack of understanding of the disease, primary-care physicians' lack of knowledge, and assumptions about typical menstrual pain.[101] On average, those later diagnosed with endometriosis waited 2.3 years after the onset of symptoms before seeking treatment, and nearly three-quarters of women receive a misdiagnosis before endometriosis.[102] Self-help groups say practitioners delay making the diagnosis, often because they do not consider it a possibility. There is a typical delay of 7–12 years from symptom onset in affected individuals to professional diagnosis.[103] There is a general lack of knowledge about endometriosis among primary care physicians. Half of the general health care providers surveyed in a 2013 study could not name three symptoms of endometriosis.[104] Healthcare providers are also likely to dismiss described symptoms as normal menstruation.[105] Younger patients may also feel uncomfortable discussing symptoms with a physician. Patients are made to categorise their pain using the pain scale. However, this is not representative of endometriosis specific pain levels which impacts diagnosis and treatment.[106]

Race and ethnicity

Race and ethnicity may impact how endometriosis affects one's life. Endometriosis is less thoroughly studied among Black people, and the research that has been done is outdated.[107][108] Cultural differences among ethnic groups also contribute to attitudes toward and treatment of endometriosis, especially in Hispanic or Latino communities. A study done in Puerto Rico in 2020 found that health care and interactions with friends and family related to discussing endometriosis were affected by stigma.[109] The most common finding was a referral to those expressing pain related to endometriosis as "changuería" or "changas", terms used in Puerto Rico to describe pointless whining and complaining, often directed at children.[109]

Stigma

The existing stigma surrounding women's health, specifically endometriosis, can lead to patients not seeking diagnoses, lower quality of healthcare, increased barriers to care and treatment, and negative reception from members of society.[110] Additionally, menstrual stigma significantly contributes to the broader issue of endometriosis stigma, creating an interconnected challenge that extends beyond reproductive health.[111][112] Widespread awareness campaigns, developments, and implementations aimed at multilevel anti-stigma organizational and structural changes, as well as more qualitative studies of the endometriosis stigma, help to overcome the harm of the phenomenon.[110]

Remove ads

Research directions

A priority area of research is the search for endometriosis biomarkers, which can help with earlier diagnoses.[113] Studies have examined potential biomarkers such as microRNAs, glycoproteins, and immune markers in blood, menstrual and urine samples, but none have shown the high accurarcy needed for clinical use yet. CA-125, a tumor marker, has been studied extensively. It is elevated in endometriosis, but also in many other conditions, and cannot be used on its own. MicroRNAs might be most promosing, but the high diversity in expression makes them a challenging target.[114]

Medical management of endometriosis is typically based on hormonal therapy, but these treatments can produce undesirable side effects, driving the search for alternatives. Emerging strategies target endometriosis as an inflammatory, metabolic, or pain disorder. Anti-inflammatory approaches include anakinra, a drug used in rheumatoid arthritis. Pain-focused treatments under investigation include cannabinoid extracts, migraine medications, and therapies directed at affected nerves. Additionally, the cancer drug dichloroacetic acid is being explored for its potential metabolic effects in endometriosis.[115]

Further reading

- Clark L (22 September 2025). "A deeper understanding of endometriosis is suggesting new treatments". New Scientist (3562). London. ISSN 0262-4079. Archived from the original on 27 September 2025. Retrieved 29 September 2025.

- Wilson M (28 March 2025). ""Endometriosis Stole My Life": What It's Really Like to Live With the Condition". Glamour. Retrieved 6 December 2025.

- Fearn H (21 January 2024). "'Gaslit by doctors': UK women with endometriosis told it is 'all in their head'". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 6 December 2025.

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads