Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

World Health Organization

Specialized agency of the United Nations From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations which coordinates responses to international public health issues and emergencies.[2] It is headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland, and has 6 regional offices[3] and 150 field offices worldwide. Only sovereign states are eligible to join, and it is the largest intergovernmental health organization at the international level.[4]

The WHO's purpose is to achieve the highest possible level of health for all the world's people, defining health as "a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity."[5] The main functions of the World Health Organization include promoting the control of epidemic and endemic diseases; providing and improving the teaching and training in public health, the medical treatment of disease, and related matters; and promoting the establishment of international standards for biological products.

The WHO was established on 7 April 1948, and formally began its work on 1 September 1948.[6] It incorporated the assets, personnel, and duties of the League of Nations' Health Organization and the Paris-based Office International d'Hygiène Publique, including the International Classification of Diseases (ICD).[7] The agency's work began in earnest in 1951 after a significant infusion of financial and technical resources.[8]

The WHO's official mandate is to promote health and safety while helping the vulnerable worldwide. It provides technical assistance to countries, sets international health standards, collects data on global health issues, and serves as a forum for scientific or policy discussions related to health.[2] Its official publication, the World Health Report, provides assessments of worldwide health topics.[9]

The WHO has played a leading role in several public health achievements, most notably the eradication of smallpox, the near-eradication of polio, and the development of an Ebola vaccine. Its current priorities include communicable diseases, such as HIV/AIDS, Ebola, malaria and tuberculosis; non-communicable diseases such as heart disease and cancer; healthy diet, nutrition, and food security; occupational health; and substance abuse. The agency advocates for universal health care coverage, engagement with the monitoring of public health risks, coordinating responses to health emergencies, and promoting health and well-being generally.[10]

The WHO is governed by the World Health Assembly (WHA), which is composed of its 194 member states. The WHA elects and advises an executive board made up of 34 health specialists; selects the WHO's chief administrator, the director-general (currently Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus of Ethiopia);[11] sets goals and priorities; and approves the budget and activities. The WHO is funded primarily by contributions from member states (both assessed and voluntary), followed by private donors.

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

Origin and founding

The International Sanitary Conferences (ISC), the first of which was held on 23 June 1851, were a series of conferences that took place until 1938, about 87 years.[12] The first conference, in Paris, was almost solely concerned with cholera, which would remain the disease of major concern for the ISC for most of the 19th century. With the cause, origin, and communicability of many epidemic diseases still uncertain and a matter of scientific argument, international agreement on appropriate measures was difficult to reach.[12] Seven of these international conferences, spanning 41 years, were convened before any resulted in a multi-state international agreement. The seventh conference, in Venice in 1892, finally resulted in a convention. It was concerned only with the sanitary control of shipping traversing the Suez Canal, and was an effort to guard against importation of cholera.[13]: 65

Five years later, in 1897, a convention concerning the bubonic plague was signed by sixteen of the nineteen states attending the Venice conference. While Denmark, Sweden-Norway, and the US did not sign this convention, it was unanimously agreed that the work of the prior conferences should be codified for implementation.[14] Subsequent conferences, from 1902 until the final one in 1938, widened the diseases of concern for the ISC, and included discussions of responses to yellow fever, brucellosis, leprosy, tuberculosis, and typhoid.[15] In part as a result of the successes of the Conferences, the Pan-American Sanitary Bureau (1902), and the Office International d'Hygiène Publique or "International office of Public Hygiene" in English (1907) were soon founded. When the League of Nations was formed in 1920, it established the Health Organization of the League of Nations. After World War II, the United Nations absorbed all the other health organizations, to form the WHO.[16]

The WHO has played a crucial role in coordinating the global response to the COVID-19 pandemic, providing essential guidelines on preventive measures, supporting research on vaccines, and facilitating vaccine distribution through initiatives like COVAX.[17]

Establishment

During the 1945 United Nations Conference on International Organization, Szeming Sze, a delegate from the Republic of China, conferred with Norwegian and Brazilian delegates on creating an international health organization under the auspices of the new United Nations. After failing to get a resolution passed on the subject, Alger Hiss, the secretary general of the conference, recommended using a declaration to establish such an organization. Sze and other delegates lobbied and a declaration passed calling for an international conference on health.[18] The use of the word "world", rather than "international", emphasized the truly global nature of what the organization was seeking to achieve.[19] The constitution of the World Health Organization was signed by all 51 countries of the United Nations, and by 10 other countries, on 22 July 1946.[20] It thus became the first specialized agency of the United Nations to which every member subscribed.[21] Its constitution formally came into force on the first World Health Day on 7 April 1948, when it was ratified by the 26th member state.[20] The WHO formally began its work on September 1, 1948.[6]

The first meeting of the World Health Assembly finished on 24 July 1948, having secured a budget of US$5 million (then £1,250,000) for the 1949 year. G. Brock Chisholm was appointed director-general of the WHO, having served as executive secretary and a founding member during the planning stages,[22][19] while Andrija Štampar was the assembly's first president. Its first priorities were to control the spread of malaria, tuberculosis and sexually transmitted infections, and to improve maternal and child health, nutrition and environmental hygiene.[23] Its first legislative act was concerning the compilation of accurate statistics on the spread and morbidity of disease.[19] The logo of the World Health Organization features the Rod of Asclepius as a symbol for healing.[24]

In 1959, the WHO signed Agreement WHA 12–40 with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), which says:[25]

whenever either organization proposes to initiate a programme or activity on a subject in which the other organization has or may have a substantial interest, the first party shall consult the other with a view to adjusting the matter by mutual agreement.

The nature of this statement has led some groups and activists including Women in Europe for a Common Future to claim that the WHO is restricted in its ability to investigate the effects on human health of radiation caused by the use of nuclear power and the continuing effects of nuclear disasters in Chernobyl and Fukushima. They believe WHO must regain what they see as independence.[25][26][27] Independent WHO held a weekly vigil from 2007 to 2017 in front of WHO headquarters.[28] However, as pointed out by Foreman[29] in clause 2 it states:

In particular, and in accordance with the Constitution of the World Health Organization and the Statute of the International Atomic Energy Agency and its agreement with the United Nations together with the exchange of letters related thereto, and taking into account the respective co-ordinating responsibilities of both organizations, it is recognized by the World Health Organization that the International Atomic Energy Agency has the primary responsibility for encouraging, assisting and co-ordinating research and development and practical application of atomic energy for peaceful uses throughout the world without prejudice to the right of the World Health Organization to concern itself with promoting, developing, assisting and co-ordinating international health work, including research, in all its aspects.

The key text is highlighted in bold, the agreement in clause 2 states that the WHO is free to perform any health-related work.

Operational history

1947: The WHO established an epidemiological information service via telex.[30]: 5

1949: The Soviet Union and its constituent republics quit the WHO over the organization's unwillingness to share the penicillin recipe. They would not return until 1956.[31]

1950: A mass tuberculosis inoculation drive using the BCG vaccine gets under way.[30]: 8

1955: The malaria eradication programme was launched, although objectives were later modified. (In most areas, the programme goals became control instead of eradication.)[30]: 9

1958: Viktor Zhdanov, Deputy Minister of Health for the USSR, called on the World Health Assembly to undertake a global initiative to eradicate smallpox, resulting in Resolution WHA11.54.[32][33]: 366–371, 393, 399, 419

1965: The first report on diabetes mellitus and the creation of the International Agency for Research on Cancer.[30]: 10–11

1966: The WHO moved its headquarters from the Ariana wing at the Palace of Nations to a newly constructed headquarters elsewhere in Geneva.[34][30]

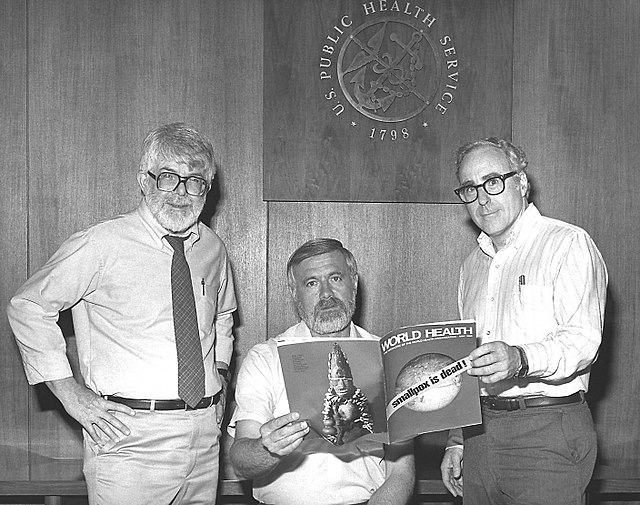

1967: The WHO intensified the global smallpox eradication campaign by contributing $2.4 million annually to the effort and adopted a new disease surveillance method,[35][36] at a time when 2 million people were dying from smallpox per year.[37] The initial problem the WHO team faced was inadequate reporting of smallpox cases. WHO established a network of consultants who assisted countries in setting up surveillance and containment activities.[38] The WHO also helped contain the last European outbreak in Yugoslavia in 1972.[39] After over two decades of fighting smallpox, a Global Commission declared in 1979 that the disease had been eradicated – the first disease in history to be eliminated by human effort.[40]

1974: The Expanded Programme on Immunization[30]: 13 and the control programme of onchocerciasis was started, an important partnership between the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and the World Bank.[30]: 14

1975: The WHO launched the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical diseases (the TDR).[30]: 15 Co-sponsored by UNICEF, UNDP, and the World Bank, it was established in response to a 1974 request from the WHA for an intensive effort to develop improved control of tropical diseases. The TDR's goals are, firstly, to support and coordinate international research into diagnosis, treatment and control of tropical diseases; and, secondly, to strengthen research capabilities within endemic countries.[41]

1976: The WHA enacted a resolution on disability prevention and rehabilitation, with a focus on community-driven care.[30]: 16

1977 and 1978: The first list of essential medicines was drawn up,[30]: 17 and a year later the ambitious goal of "Health For All" was declared.[30]: 18

1986: The WHO began its global programme on HIV/AIDS.[30]: 20 Two years later preventing discrimination against patients was attended to[30]: 21 and in 1996 the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) was formed.[30]: 23

1988: The Global Polio Eradication Initiative was established.[30]: 22

1995: The WHO established an independent International Commission for the Certification of Dracunculiasis Eradication (Guinea worm disease eradication; ICCDE).[30]: 23 The ICCDE recommends to the WHO which countries fulfil requirements for certification. It also has role in advising on progress made towards elimination of transmission and processes for verification.[42]

1998: The WHO's director-general highlighted gains in child survival, reduced infant mortality, increased life expectancy and reduced rates of "scourges" such as smallpox and polio on the fiftieth anniversary of WHO's founding. He, did, however, accept that more had to be done to assist maternal health and that progress in this area had been slow.[43]

2000: The Stop TB Partnership was created along with the UN's formulation of the Millennium Development Goals.[30]: 24

2001: The measles initiative was formed, and credited with reducing global deaths from the disease by 68% by 2007.[30]: 26

2002: The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria was drawn up to improve the resources available.[30]: 27

2005: The WHO revises International Health Regulations (IHR) in light of emerging health threats and the experience of the 2002/3 SARS epidemic, authorizing WHO, among other things, to declare a health threat a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.[44]

2006: The WHO endorsed the world's first official HIV/AIDS Toolkit for Zimbabwe, which formed the basis for global prevention, treatment, and support the plan to fight the AIDS pandemic.[45][46]

2006: The WHO launches the Global action plan for influenza vaccines

2016: The Global action plan for influenza vaccines ends with a report which concludes that while substantial progress has been made over the 10 years of the Plan, the world is still not ready to respond to an influenza pandemic.

2016: Following the perceived failure of the response to the West Africa Ebola outbreak, the World Health Emergencies programme was formed, changing the WHO from just being a "normative" agency to one that responds operationally to health emergencies.[47]

2020: the World Health Organization announced that it had classified the novel coronavirus outbreak as a public health emergency of international concern. The novel coronavirus was a new strain of coronavirus that had never been detected in humans before. The WHO named this new coronavirus "COVID-19" or "2019-nCov".

2022: The WHO suggests formation of a Global Health Emergency Council, with a new global health emergency workforce, and recommends revision of the International Health Regulations.[48]

2024: WHO has declared the spread of mpox (formerly monkeypox) in several African countries a public health emergency of international concern, marking the second such declaration in the last two years due to the virus's transmission.[49][50][51]

Remove ads

Policies and objectives

Summarize

Perspective

Overall focus

The WHO's Constitution states that its objective "is the attainment by all people of the highest possible level of health".[52]

The WHO seeks to fulfill this objective through its functions as defined in its Constitution:

- To act as the directing and coordinating authority on international health work;

- To establish and maintain effective collaboration with the United Nations, specialized agencies, governmental health administrations, professional groups and such other organizations as may be deemed appropriate;

- To assist Governments, upon request, in strengthening health services;

- To furnish appropriate technical assistance and, in emergencies, necessary aid upon the request or acceptance of Governments;

- To provide or assist in providing, upon the request of the United Nations, health services and facilities to special groups, such as the peoples of trust territories;

- To establish and maintain such administrative and technical services as may be required, including epidemiological and statistical services;

- To stimulate and advance work to eradicate epidemic, endemic and other diseases;

- To promote, in co-operation with other specialized agencies where necessary, the prevention of accidental injuries;

- To promote, in co-operation with other specialized agencies where necessary, the improvement of nutrition, housing, sanitation, recreation, economic or working conditions and other aspects of environmental hygiene;

- To promote co-operation among scientific and professional groups which contribute to the advancement of health;

- To propose conventions, agreements and regulations, and make recommendations with respect to international health matters and to perform (Article 2 of the Constitution).

As of 2012[update], the WHO has defined its role in public health as follows:[53]

- providing leadership on matters critical to health and engaging in partnerships where joint action is needed;

- shaping the research agenda and stimulating the generation, translation, and dissemination of valuable knowledge;[54]

- setting norms and standards and promoting and monitoring their implementation;

- articulating ethical and evidence-based policy options;

- providing technical support, catalysing change, and building sustainable institutional capacity; and

- monitoring the health situation and assessing health trends.

- CRVS (civil registration and vital statistics) to provide monitoring of vital events (birth, death, wedding, divorce).[55]

Since the late 20th century, the rise of new actors engaged in global health—such as the World Bank, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and dozens of public-private partnerships for global health—have weakened the WHO's role as a coordinator and policy leader in the field; subsequently, there are various proposals to reform or reorient the WHO's role and priorities in public health, ranging from narrowing its mandate to strengthening its independence and authority.[56]

In line with a growing global trend, as documented by the OECD[57] and established at the EU,[58] the WHO has embraced increased public participation in health policymaking.[59][60][61] This is in alignment with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)[62] and other intergovernmental agreements, and means "empowering people, communities and civil society through inclusive participation in decision-making processes that affect health across the policy cycle and at all levels of the system."[63]

Communicable diseases

During the 1970s, WHO had dropped its commitment to a global malaria eradication campaign as too ambitious, it retained a strong commitment to malaria control. WHO's Global Malaria Programme works to keep track of malaria cases, and future problems in malaria control schemes. As of 2012, the WHO was to report as to whether RTS,S/AS01, were a viable malaria vaccine. For the time being, insecticide-treated mosquito nets and insecticide sprays are used to prevent the spread of malaria, as are antimalarial drugs – particularly to vulnerable people such as pregnant women and young children.[64]

In 1988, WHO launched the Global Polio Eradication Initiative to eradicate polio.[65] It has also been successful in helping to reduce cases by 99% since WHO partnered with Rotary International, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), and smaller organizations. As of 2011[update], it has been working to immunize young children and prevent the re-emergence of cases in countries declared "polio-free".[66] In 2017, a study was conducted as to why Polio Vaccines may not be enough to eradicate the Virus & conduct new technology. Polio is now on the verge of extinction, thanks to a Global Vaccination Drive. The World Health Organization (WHO) stated the eradication programme has saved millions from deadly disease.[67]

Between 1990 and 2010, WHO's help has contributed to a 40% decline in the number of deaths from tuberculosis, and since 2005, over 46 million people have been treated and an estimated 7 million lives saved through practices advocated by WHO. These include engaging national governments and their financing, early diagnosis, standardizing treatment, monitoring of the spread and effect of tuberculosis, and stabilizing the drug supply. It has also recognized the vulnerability of victims of HIV/AIDS to tuberculosis.[68]

In 2003, the WHO denounced the Roman Curia's health department's opposition to the use of condoms, saying: "These incorrect statements about condoms and HIV are dangerous when we are facing a global pandemic which has already killed more than 20 million people, and currently affects at least 42 million."[69] As of 2009[update], the Catholic Church remains opposed to increasing the use of contraception to combat HIV/AIDS.[70] At the time, the World Health Assembly president, Guyana's Health Minister Leslie Ramsammy, condemned Pope Benedict's opposition to contraception, saying he was trying to "create confusion" and "impede" proven strategies in the battle against the disease.[71]

In 2007, the WHO organized work on pandemic influenza vaccine development through clinical trials in collaboration with many experts and health officials.[72] A pandemic involving the H1N1 influenza virus was declared by the then director-general Margaret Chan in April 2009.[73] Margret Chan declared in 2010 that the H1N1 has moved into the post-pandemic period.[74] By the post-pandemic period, critics claimed the WHO had exaggerated the danger, spreading "fear and confusion" rather than "immediate information".[75] Industry experts countered that the 2009 pandemic had led to "unprecedented collaboration between global health authorities, scientists and manufacturers, resulting in the most comprehensive pandemic response ever undertaken, with a number of vaccines approved for use three months after the pandemic declaration. This response was only possible because of the extensive preparations undertaken during the last decade".[76]

The 2012–2013 WHO budget identified five areas among which funding was distributed.[77]: 5, 20 Two of those five areas related to communicable diseases: the first, to reduce the "health, social and economic burden" of communicable diseases in general; the second to combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis in particular.[77]: 5, 26

As of 2015[update], the World Health Organization has worked within the UNAIDS network and strives to involve sections of society other than health to help deal with the economic and social effects of HIV/AIDS.[78] In line with UNAIDS, WHO has set itself the interim task between 2009 and 2015 of reducing the number of those aged 15–24 years who are infected by 50%; reducing new HIV infections in children by 90%; and reducing HIV-related deaths by 25%.[79]

The World Health Organization's definition of neglected tropical disease has been criticized to be restrictive (focusing only on communicable diseases) and described as a form of epistemic injustice, where conditions like snakebite are forced to be framed as a medical problem.[80]

Non-communicable diseases

One of the thirteen WHO priority areas is aimed at the prevention and reduction of "disease, disability and premature deaths from chronic noncommunicable diseases, mental disorders, violence and injuries, and visual impairment which are collectively responsible for almost 71% of all deaths worldwide".[77][81][82] The Division of Noncommunicable Diseases for Promoting Health through the Reproductive Health has published the magazine, Entre Nous, across Europe since 1983.[83]

WHO is mandated under two of the international drug control conventions (Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961 and Convention on Psychotropic Substances, 1971) to carry out scientific assessments of substances for international drug control. Through the WHO Expert Committee on Drug Dependence (ECDD), it can recommend changes to scheduling of substances to the United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs.[84] The ECDD is in charge of evaluating "the impact of psychoactive substances on public health" and "their dependence producing properties and potential harm to health, as well as considering their potential medical benefits and therapeutic applications."[85]

Environmental health

The WHO estimates that 12.6 million people died as a result of living or working in an unhealthy environment in 2012 – this accounts for nearly 1 in 4 of total global deaths. Environmental risk factors, such as air, water, and soil pollution, chemical exposures, climate change, and ultraviolet radiation, contribute to more than 100 diseases and injuries. This can result in a number of pollution-related diseases.

- 2018 (30 October – 1 November): 1 WHO's first global conference on air pollution and health (Improving air quality, combatting climate change – saving lives); organized in collaboration with UN Environment, World Meteorological Organization (WMO), and the secretariat of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)[86]

Life course and lifestyle

WHO works to "reduce morbidity and mortality and improve health during key stages of life, including pregnancy, childbirth, the neonatal period, childhood and adolescence, and improve sexual and reproductive health and promote active and healthy aging for all individuals", for instance with the Special Programme on Human Reproduction.[77]: 39–45 [87]

It also tries to prevent or reduce risk factors for "health conditions associated with use of tobacco, alcohol, drugs and other psychoactive substances, unhealthy diets and physical inactivity and unsafe sex".[77]: 50–55 [88][89]

The WHO works to improve nutrition, food safety and food security and to ensure this has a positive effect on public health and sustainable development.[77]: 66–71

In April 2019, the WHO released new recommendations stating that children between the ages of two and five should spend no more than one hour per day engaging in sedentary behaviour in front of a screen and that children under two should not be permitted any sedentary screen time.[90]

In January 2025, the WHO released a new guideline Use of lower-sodium salt substitutes which strongly recommends reducing sodium intake to less than 2 g/day and conditionally recommends replacing regular table salt with lower-sodium salt substitutes that contain potassium. This recommendation is intended for adults (not pregnant women or children) in general populations, excluding individuals with kidney impairments or with other circumstances or conditions that might compromise potassium excretion.[91][92][93]

Surgery and trauma care

The World Health Organization promotes road safety as a means to reduce traffic-related injuries.[94] It has also worked on global initiatives in surgery, including emergency and essential surgical care,[95] trauma care,[96] and safe surgery.[97] The WHO Surgical Safety Checklist is in current use worldwide in the effort to improve patient safety.[97]

Emergency work

The World Health Organization's primary objective in natural and man-made emergencies is to coordinate with member states and other stakeholders to "reduce avoidable loss of life and the burden of disease and disability."[77]: 46–49

On 5 May 2014, WHO announced that the spread of polio was a world health emergency – outbreaks of the disease in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East were considered "extraordinary".[98][99]

On 8 August 2014, WHO declared that the spread of Ebola was a public health emergency; an outbreak which was believed to have started in Guinea had spread to other nearby countries such as Liberia and Sierra Leone. The situation in West Africa was considered very serious.[100]

Reform efforts following the Ebola outbreak

Following the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, the organization was heavily criticized for its bureaucracy, insufficient financing, regional structure, and staffing profile.[101]

An internal WHO report on the Ebola response pointed to underfunding and the lack of "core capacity" in health systems in developing countries as the primary weaknesses of the existing system. At the annual World Health Assembly in 2015, Director-General Margaret Chan announced a $100 million Contingency Fund for rapid response to future emergencies,[102][103] of which it had received $26.9 million by April 2016 (for 2017 disbursement). WHO has budgeted an additional $494 million for its Health Emergencies Programme in 2016–17, for which it had received $140 million by April 2016.[104]

The program was aimed at rebuilding WHO capacity for direct action, which critics said had been lost due to budget cuts in the previous decade that had left the organization in an advisory role dependent on member states for on-the-ground activities. In comparison, billions of dollars have been spent by developed countries on the 2013–2016 Ebola epidemic and 2015–16 Zika epidemic.[105]

Response to the COVID-19 pandemic

The WHO created an Incident Management Support Team on 1 January 2020, one day after Chinese health authorities notified the organization of a cluster of pneumonia cases of unknown aetiology.[106][107][108] On 5 January the WHO notified all member states of the outbreak,[109] and in subsequent days provided guidance to all countries on how to respond,[109] and confirmed the first infection outside China.[110] On 14 January 2020, the WHO announced that preliminary investigations conducted by Chinese authorities had found no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) identified in Wuhan.[111] The same day, the organization warned of limited human-to-human transmission, and confirmed human-to-human transmission one week later.[112][113][114] On 30 January the WHO declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC),[115][116][117] considered a "call to action" and "last resort" measure for the international community and a pandemic on 11 March.[118]

While organizing the global response to the COVID-19 pandemic and overseeing "more than 35 emergency operations" for cholera, measles and other epidemics internationally,[106] the WHO has been criticized for praising China's public health response to the crisis while seeking to maintain a "diplomatic balancing act" between the United States and China.[108][119][120][121] David L. Heymann, professor of infectious disease epidemiology at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, said that "China has been very transparent and open in sharing its data... and they opened up all of their files with the WHO present."[122]

The WHO faced criticism from the United States' Trump administration while "guid[ing] the world in how to tackle the deadly" COVID-19 pandemic.[106] On 14 April 2020, United States president Donald Trump said that he would halt United States funding to the WHO while reviewing its role in "severely mismanaging and covering up the spread of the coronavirus."[123] World leaders and health experts largely condemned President Trump's announcement, which came amid criticism of his response to the outbreak in the United States.[124] WHO called the announcement "regrettable" and defended its actions in alerting the world to the emergence of COVID-19.[125] On 8 May 2020, the United States blocked a vote on a U.N. Security Council resolution aimed at promoting nonviolent international cooperation during the pandemic, and mentioning the WHO.[126] On 7 July 2020, President Trump formally notified the UN of his intent to withdraw the United States from the WHO.[127] However, Trump's successor, President Joe Biden, cancelled the planned withdrawal and announced in January 2021 that the U.S. would resume funding the organization.[128][129][130]

In May 2023, the WHO announced that COVID-19 was no longer a world-wide health emergency.[131]

In January 2025, during his second term, President Trump issued an executive order to withdraw the United States from the WHO, citing their alleged mishandling of the COVID-19 pandemic originating in Wuhan, among other reasons.[132][133] The United States of America will leave the World Health Organization in January 2026.[134] Meanwhile, the US ceased to cooperate with the WHO.[135]

Health policy

WHO addresses government health policy with two aims: firstly, "to address the underlying social and economic determinants of health through policies and programmes that enhance health equity and integrate pro-poor, gender-responsive, and human rights-based approaches" and secondly "to promote a healthier environment, intensify primary prevention and influence public policies in all sectors so as to address the root causes of environmental threats to health".[77]: 61–65

The organization develops and promotes the use of evidence-based tools, norms and standards to support member states to inform health policy options. It oversees the implementation of the International Health Regulations, and publishes a series of medical classifications; of these, three are over-reaching "reference classifications": the International Statistical Classification of Diseases (ICD), the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) and the International Classification of Health Interventions (ICHI).[136] Other international policy frameworks produced by WHO include the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes (adopted in 1981),[137] Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (adopted in 2003)[138] the Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel (adopted in 2010)[139] as well as the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines and its pediatric counterpart. An international convention on pandemic prevention and preparedness is being actively considered.[140]

In terms of health services, WHO looks to improve "governance, financing, staffing and management" and the availability and quality of evidence and research to guide policy. It also strives to "ensure improved access, quality and use of medical products and technologies".[77]: 72–83 WHO – working with donor agencies and national governments – can improve their reporting about use of research evidence.[141]

Digital Health

On Digital Health topics, WHO has existing Inter-Agency collaboration with the International Telecommunication Union (the UN Specialized Agency for ICT), including the Be Health, Be Mobile initiate and the ITU-WHO Focus Group on Artificial Intelligence for Health.

Policy packages

The WHO has developed several technical policy packages to support countries to improve health:[142]

- ACTIVE (physical activity)

- HEARTS (cardiovascular diseases)

- MPOWER (tobacco control)

- REPLACE (trans fat)

- SAFER (alcohol)

- SHAKE (salt reduction)

Governance and support

The remaining two of WHO's thirteen identified policy areas relate to the role of WHO itself:[77]: 84–91

- "to provide leadership, strengthen governance and foster partnership and collaboration with countries, the United Nations system, and other stakeholders in order to fulfil the mandate of WHO in advancing the global health agenda"; and

- "to develop and sustain WHO as a flexible, learning organization, enabling it to carry out its mandate more efficiently and effectively".

Partnerships

The WHO along with the World Bank constitute the core team responsible for administering the International Health Partnership (IHP+). The IHP+ is a group of partner governments, development agencies, civil society, and others committed to improving the health of citizens in developing countries. Partners work together to put international principles for aid effectiveness and development co-operation into practice in the health sector.[143]

The organization relies on contributions from renowned scientists and professionals to inform its work, such as the WHO Expert Committee on Biological Standardization,[144] the WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy,[145] and the WHO Study Group on Interprofessional Education & Collaborative Practice.[146]

WHO runs the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, targeted at improving health policy and systems.[147]

WHO also aims to improve access to health research and literature in developing countries such as through the HINARI network.[148]

WHO collaborates with The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, UNITAID, and the United States President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief[149] to spearhead and fund the development of HIV programs.

WHO created the Civil Society Reference Group on HIV,[149] which brings together other networks that are involved in policymaking and the dissemination of guidelines.

WHO, a sector of the United Nations, partners with UNAIDS[149] to contribute to the development of HIV responses in different areas of the world.

WHO facilitates technical partnerships through the Technical Advisory Committee on HIV,[150] which they created to develop WHO guidelines and policies.

In 2014, WHO released the Global Atlas of Palliative Care at the End of Life in a joint publication with the Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance, an affiliated NGO working collaboratively with the WHO to promote palliative care in national and international health policy.[151][152]

Public health education and action

The practice of empowering individuals to exert more control over and make improvements to their health is known as health education, as described by the WHO. It shifts away from an emphasis on personal behaviour and toward a variety of societal and environmental solutions.[153]

Each year, the organization marks World Health Day and other observances focusing on a specific health promotion topic. World Health Day falls on 7 April each year, timed to match the anniversary of WHO's founding. Recent themes have been vector-borne diseases (2014), healthy ageing (2012) and drug resistance (2011).[154]

The other official global public health campaigns marked by WHO are World Tuberculosis Day, World Immunization Week, World Malaria Day, World No Tobacco Day, World Blood Donor Day, World Hepatitis Day, and World AIDS Day.

As part of the United Nations, the World Health Organization supports work towards the Millennium Development Goals.[155] Of the eight Millennium Development Goals, three – reducing child mortality by two-thirds, to reduce maternal deaths by three-quarters, and to halt and begin to reduce the spread of HIV/AIDS – relate directly to the WHO's scope; the other five inter-relate and affect world health.[156]

Data handling and publications

The World Health Organization works to provide the needed health and well-being evidence through a variety of data collection platforms, including the World Health Survey covering almost 400,000 respondents from 70 countries,[157] and the Study on Global Aging and Adult Health (SAGE) covering over 50,000 persons over 50 years old in 23 countries.[158] The Country Health Intelligence Portal (CHIP), has also been developed to provide an access point to information about the health services that are available in different countries.[159] The information gathered in this portal is used by the countries to set priorities for future strategies or plans, implement, monitor, and evaluate it.

The WHO has published various tools for measuring and monitoring the capacity of national health systems[160] and health workforces.[161] The Global Health Observatory (GHO) has been the WHO's main portal which provides access to data and analyses for key health themes by monitoring health situations around the globe.[162]

The WHO Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems (WHO-AIMS), the WHO Quality of Life Instrument (WHOQOL), and the Service Availability and Readiness Assessment (SARA) provide guidance for data collection.[163] Collaborative efforts between WHO and other agencies, such as through the Health Metrics Network, also aim to provide sufficient high-quality information to assist governmental decision making.[164] WHO promotes the development of capacities in member states to use and produce research that addresses their national needs, including through the Evidence-Informed Policy Network (EVIPNet).[165] The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO/AMRO) became the first region to develop and pass a policy on research for health approved in September 2009.[166]

On 10 December 2013, a new WHO database, known as MiNDbank, went online. The database was launched on Human Rights Day, and is part of WHO's QualityRights initiative, which aims to end human rights violations against people with mental health conditions. The new database presents a great deal of information about mental health, substance abuse, disability, human rights, and the different policies, strategies, laws, and service standards being implemented in different countries.[167] It also contains important international documents and information. The database allows visitors to access the health information of WHO member states and other partners. Users can review policies, laws, and strategies and search for the best practices and success stories in the field of mental health.[167]

The WHO regularly publishes a World Health Report, its leading publication, including an expert assessment of a specific global health topic.[168] Other publications of WHO include the Bulletin of the World Health Organization,[169] the Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal (overseen by EMRO),[170] the Human Resources for Health (published in collaboration with BioMed Central),[171] and the Pan American Journal of Public Health (overseen by PAHO/AMRO).[172]

In 2016, the World Health Organization drafted a global health sector strategy on HIV. In the draft, the World Health Organization outlines its commitment to ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 with interim targets for the year 2020. To make achievements towards these targets, the draft lists actions that countries and the WHO can take, such as a commitment to universal health coverage, medical accessibility, prevention and eradication of disease, and efforts to educate the public. Some notable points made in the draft include tailoring resources to mobilized regions where the health system may be compromised due to natural disasters, etc. Among the points made, it seems clear that although the prevalence of HIV transmission is declining, there is still a need for resources, health education, and global efforts to end this epidemic.[173]

The WHO has a Framework Convention on Tobacco implementation database which is one of the few mechanisms to help enforce compliance with the FCTC.[174] However, there have been reports of numerous discrepancies between it and national implementation reports on which it was built. As researchers Hoffman and Rizvi report "As of July 4, 2012, 361 (32·7%) of 1104 countries' responses were misreported: 33 (3·0%) were clear errors (e.g., database indicated 'yes' when report indicated 'no'), 270 (24·5%) were missing despite countries having submitted responses, and 58 (5·3%) were, in our opinion, misinterpreted by WHO staff".[175]

WHO has been moving toward acceptance and integration of traditional medicine and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). In 2022, the new International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, ICD-11, will attempt to enable classifications from traditional medicine to be integrated with classifications from evidence-based medicine. Though Chinese authorities have pushed for the change, this and other support of the WHO for traditional medicine has been criticized by the medical and scientific community, due to lack of evidence and the risk of endangering wildlife hunted for traditional remedies.[176][177][178] A WHO spokesman said that the inclusion was "not an endorsement of the scientific validity of any Traditional Medicine practice or the efficacy of any Traditional Medicine intervention."[177]

International Agency for Research on Cancer

The WHO sub-department, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), conducts and coordinates research into the causes of cancer.[179] It also collects and publishes surveillance data regarding the occurrence of cancer worldwide.[180]

Its Monographs Programme identifies carcinogenic hazards and evaluates environmental causes of cancer in humans.[181][182]

Remove ads

Structure and governance

Summarize

Perspective

The World Health Organization is a member of the United Nations Development Group.[183]

Membership

As of January 2025[update], the WHO has 194 member states: all member states of the United Nations except for Liechtenstein (192 countries), plus the Cook Islands and Niue.[184][185] A state becomes a full member of WHO by ratifying the treaty known as the Constitution of the World Health Organization. As of January 2025, it also had two associate members, Puerto Rico and Tokelau.[186][185] The WHO two-year budget for 2022–2023 is paid by its 194 members and 2 associate members.[185] Several other countries have been granted observer status. Palestine is an observer as a "national liberation movement" recognized by the League of Arab States under United Nations Resolution 3118. The Sovereign Military Order of Malta (or Order of Malta) also attends on an observer basis. The Holy See attends as an observer, and its participation as "non-Member State Observer" was formalized by an Assembly resolution in 2021.[187][188] The government of Taiwan was allowed to participate under the designation "Chinese Taipei" as an observer from 2009 to 2016, but has not been invited again since.[189] On 20 January 2025, U.S. President Donald Trump signed Executive Order 14155 initiating the 12-month process of withdrawing the U.S. from the WHO.[190][191][192] On 5 February 2025, Argentinian president Javier Milei announced that Argentina would also be withdrawing from WHO.[193]

WHO member states appoint delegations to the World Health Assembly, the WHO's supreme decision-making body. All UN member states are eligible for WHO membership, and, according to the WHO website, "other countries may be admitted as members when their application has been approved by a simple majority vote of the World Health Assembly".[184] The World Health Assembly is attended by delegations from all member states, and determines the policies of the organization.

The executive board is composed of members technically qualified in health and gives effect to the decisions and policies of the World Health Assembly. In addition, the UN observer organizations International Committee of the Red Cross and International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies have entered into "official relations" with WHO and are invited as observers. In the World Health Assembly, they are seated alongside the other NGOs.[188]

Membership and participation of the Republic of China

The Republic of China (ROC), whose government controlled Mainland China from 1912 to 1949 and currently controls Taiwan since 1945 following World War II, was the founding member of WHO since its inception and had represented "China" in the organization. The adoption of the United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2758 in 1971, however, had the representation of "China" handed over to the People's Republic of China (PRC), and led to the expulsion of the Republic of China from WHO and other UN bodies. Since that time, per the One-China policy, both the ROC and PRC lay claims of sovereignty to each other's territory.[194][195]

In May 2009, the Department of Health of the Republic of China was invited by the WHO to attend the 62nd World Health Assembly as an observer under the name "Chinese Taipei". This was the ROC's first participation at WHO meetings since 1971, as a result of the improved cross-strait relations since Ma Ying-jeou became the president of the Republic of China a year before.[196] Its participation with WHO ended due to diplomatic pressure from the PRC following the election in 2016 that brought the independence-minded Democratic Progressive Party back into power.[197]

Political pressure from the PRC has led to the ROC being barred from membership of the WHO and other UN-affiliated organizations, and in 2017 to 2020 the WHO refused to allow Taiwanese delegates to attend the WHO annual assembly.[198] According to Taiwanese publication The News Lens, on multiple occasions Taiwanese journalists have been denied access to report on the assembly.[199]

In May 2018, the WHO denied access to its annual assembly by Taiwanese media, reportedly due to demands from the PRC.[200] Later in May 172 members of the United States House of Representatives wrote to the director-general of the World Health Organization to argue for Taiwan's inclusion as an observer at the WHA.[201] The United States, Japan, Germany, and Australia all support Taiwan's inclusion in WHO.[202]

Pressure to allow the ROC to participate in WHO increased as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic with Taiwan's exclusion from emergency meetings concerning the outbreak bringing a rare united front from Taiwan's diverse political parties. Taiwan's main opposition party, the Kuomintang (KMT, Chinese Nationalist Party), expressed their anger at being excluded arguing that disease respects neither politics nor geography. China once again dismissed concerns over Taiwanese inclusion with the foreign minister claiming that no-one cares more about the health and wellbeing of the Taiwanese people than central government of the PRC.[203] During the outbreak Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau[204] voiced his support for Taiwan's participation in WHO, as did Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.[197] In January 2020 the European Union, a WHO observer, backed Taiwan's participation in WHO meetings related to the coronavirus pandemic as well as their general participation.[205]

In a 2020 interview, Assistant Director-General Bruce Aylward appeared to dodge a question from RTHK reporter Yvonne Tong about Taiwan's response to the pandemic and inclusion in the WHO, blaming internet connection issues.[206] When the video chat was restarted, he was asked another question about Taiwan. He responded by indicating that they had already discussed China and formally ended the interview.[207] This incident led to accusations about the PRC's political influence over the international organization.[208][209]

Taiwan's effective response to the 2019–20 COVID-19 pandemic has bolstered its case for WHO membership. Taiwan's response to the outbreak has been praised by a number of experts.[210][211] In early May 2020, New Zealand Foreign Minister Winston Peters expressed support for the ROC's bid to rejoin the WHO during a media conference.[212][213] The New Zealand Government subsequently supporting Taiwan's bid to join the WHO, putting NZ alongside Australia and the United States who have taken similar positions.[214][215]

On 9 May, Congressmen Eliot Engel, the Democratic chairman of the United States House Committee on Foreign Affairs, Michael McCaul, the House Committee's ranking Republican member, Senator Jim Risch, the Republican chairman of the United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, and Senator Bob Menendez, the Senate Committee's ranking Democratic member, submitted a joint letter to nearly 60 "like-minded" countries including Canada, Thailand, Japan, Germany, the United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia, and Australia, urging them to support ROC's participation in the World Health Organization.[216][217]

In November 2020, the word "Taiwan" was blocked in comments on a livestream on the WHO's Facebook page.[218]

Membership and participation of the United States

On 14 April 2020, United States president Donald Trump said that he would halt United States funding to the WHO while reviewing its role in "severely mismanaging and covering up the spread of the coronavirus."[123] World leaders and health experts largely condemned President Trump's announcement, which came amid criticism of his response to the outbreak in the United States.[124] WHO called the announcement "regrettable" and defended its actions in alerting the world to the emergence of COVID-19.[125] On 7 July 2020, President Trump formally notified the UN of his intent to withdraw the United States from the WHO.[127] However, Trump's successor, president Joe Biden, cancelled the planned withdrawal and announced in January 2021 that the U.S. would resume funding the organization.[128][129][130] On 20 January 2025, an executive order was signed by a re-inaugurated Trump, formally notifying the United Nations of his intent to withdraw the United States from the WHO for a second time.[191][219]

World Health Assembly and Executive Board

The World Health Assembly (WHA) is the legislative and supreme body of the WHO. Based in Geneva, it typically meets yearly in May. It appoints the director-general every five years and votes on matters of policy and finance of WHO, including the proposed budget. It also reviews reports of the executive board and decides whether there are areas of work requiring further examination.

The Assembly elects 34 members, technically qualified in the field of health, to the executive board for three-year terms. The main functions of the board are to carry out the decisions and policies of the Assembly, to advise it, and to facilitate its work.[220] As of June 2023, the chair of the executive board is Dr. Hanan Mohamed Al Kuwari of Qatar.[221]

Director-General

The head of the organization is the director-general, elected by the World Health Assembly.[222] The term lasts for five years, and directors-general are typically appointed in May, when the Assembly meets. The current director-general is Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, who was appointed on 1 July 2017.[223]

Global institutions

Apart from regional, country, and liaison offices, the World Health Assembly has also established other institutions for promoting and carrying on research.[224]

Personnel

The WHO employs 7,000 people in 149 countries and regions to carry out its principles.[226] In support of the principle of a tobacco-free work environment, the WHO does not recruit cigarette smokers.[227] The organization has previously instigated the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in 2003.[228]

Goodwill Ambassadors

The WHO operates "Goodwill Ambassadors"; members of the arts, sports, or other fields of public life aimed at drawing attention to the WHO's initiatives and projects. There are currently five Goodwill Ambassadors (Jet Li, Nancy Brinker, Peng Liyuan, Yohei Sasakawa and the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra) and a further ambassador associated with a partnership project (Craig David).[229]

On 21 October 2017, the director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus appointed the then Zimbabwean president Robert Mugabe as a WHO Goodwill Ambassador to help promote the fight against non-communicable diseases. The appointment address praised Mugabe for his commitment to public health in Zimbabwe. The appointment attracted widespread condemnation and criticism in WHO member states and international organizations due to Robert Mugabe's poor record on human rights and presiding over a decline in Zimbabwe's public health.[230][231] Due to the outcry, the following day the appointment was revoked.[232]

Medical Society of the World Health Organization

Since the beginning,[233] the WHO has had the Medical Society of the World Health Organization. It has conducted lectures by noted researchers and published findings, recommendations.[234][235][236][237][238][239][240][241][excessive citations] The founder, Dr. S. William A. Gunn[242] has been its president.[243] In 1983, Murray Eden was awarded the WHO Medical Society medal, for his work as consultant on research and development for WHO's director-general.[244]

Financing and partnerships

This section needs to be updated. (November 2024) |

The WHO is financed by contributions from member states and outside donors. In 2020–21, the largest contributors were the Germany, Gates Foundation, United States, United Kingdom and European Commission.[245] The WHO Executive Board formed a Working Group on Sustainable Financing in 2021, charged to rethink WHO's funding strategy and present recommendations.[246] Its recommendations were adopted by the 2022 World Health Assembly,[247] the key one being to raise compulsory member dues to a level equal to 50% of WHO's 2022–2023 base budget by the end of the 2020s.[248]

- Assessed contributions are the dues the Member States pay depending on the states' wealth and population

- Voluntary contributions specified are funds for specific programme areas provided by the Member States or other partners

- Core voluntary contributions are funds for flexible uses provided by the Member States or other partners

Past

At the beginning of the 21st century, the WHO's work involved increasing collaboration with external bodies.[260] As of 2002[update], a total of 473 nongovernmental organizations (NGO) had some form of partnership with WHO. There were 189 partnerships with international NGOs in formal "official relations" – the rest being considered informal in character.[261] Partners include the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation[262] and the Rockefeller Foundation.[263]

As of 2012[update], the largest annual assessed contributions from member states came from the United States ($110 million), Japan ($58 million), Germany ($37 million), United Kingdom ($31 million) and France ($31 million).[264] The combined 2012–2013 budget proposed a total expenditure of $3,959 million, of which $944 million (24%) will come from assessed contributions. This represented a significant fall in outlay compared to the previous 2009–2010 budget, adjusting to take account of previous underspends. Assessed contributions were kept the same. Voluntary contributions will account for $3,015 million (76%), of which $800 million is regarded as highly or moderately flexible funding, with the remainder tied to particular programmes or objectives.[265]

According to The Associated Press, the WHO routinely spends about $200 million a year on travel expenses, more than it spends to tackle mental health problems, HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria combined. In 2016, Margaret Chan, director-general of WHO from January 2007 to June 2017,[266] stayed in a $1000-per-night hotel room while visiting West Africa.[267]

The biggest contributor used to be the United States, which gives over $400 million annually.[268] U.S. contributions to the WHO are funded through the U.S. State Department's account for Contributions to International Organizations (CIO). In April 2020, U.S. President Donald Trump, with backing by members of his party,[269] announced that his administration would halt funding to the WHO.[270] Funds previously earmarked for the WHO were to be held for 60–90 days pending an investigation into the WHO's handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in respect to the organization's purported relationship with China.[271] The announcement was immediately criticized by world leaders including António Guterres, the secretary general of the United Nations; Heiko Maas, the German foreign minister; and Moussa Faki Mahamat, African Union chairman.[268] During the first two years of the pandemic, American funding of the WHO declined by a quarter, although it is expected to increase during 2022 and 2023.[272]

On 16 May 2020, the Trump administration agreed to pay up to what China pays in assessed contributions, which is less than about one-tenth of its previous funding. Biennium 2018–2019 China paid in assessed contributions US$75,796K, in specified voluntary contributions US$10,184K, for a total US$85,980K.[273][274]

WHO Public Health Prizes and Awards

World Health Organization Prizes and Awards are given to recognize major achievements in public health. The candidates are nominated and recommended by each prize and award selection panel. The WHO Executive Board selects the winners, which are presented during the World Health Assembly.[275]

Remove ads

World headquarters and offices

Summarize

Perspective

The seat of the organization is in Geneva, Switzerland. It was designed by Swiss architect Jean Tschumi and inaugurated in 1966.[276] In 2017, the organization launched an international competition to redesign and extend its headquarters.[277]

Gallery of the WHO headquarters building

- Stairwell, 1969

- Internal courtyard, 1969

- Reflecting pool, 1969

- Exterior, 1969

- From southwest, 2013

- Entrance hall, 2013

- Main conference room, 2013

Country and liaison offices

The World Health Organization operates 150 country offices in six different regions.[278] It also operates several liaison offices, including those with the European Union, United Nations and a single office covering the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. It also operates the International Agency for Research on Cancer in Lyon, France, and the WHO Centre for Health Development in Kobe, Japan.[279] Additional offices include those in Pristina; the West Bank and Gaza; the US-Mexico Border Field Office in El Paso; the Office of the Caribbean Program Coordination in Barbados; and the Northern Micronesia office.[280] There will generally be one WHO country office in the capital, occasionally accompanied by satellite-offices in the provinces or sub-regions of the country in question.

The country office is headed by a WHO Representative (WR). As of 2010[update], the only WHO Representative outside Europe to be a national of that country was for the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya ("Libya"); all other staff was international. WHO Representatives in the Region termed the Americas are referred to as PAHO/WHO Representatives. In Europe, WHO Representatives also serve as head of the country office, and are nationals except for Serbia; there are also heads of the country office in Albania, the Russian Federation, Tajikistan, Turkey, and Uzbekistan.[280] The WR is a member of the UN system country team which is coordinated by the UN System Resident Coordinator.

The country office consists of the WR, and several health and other experts, both foreign and local, as well as the necessary support staff.[278] The main functions of WHO country offices include being the primary adviser of that country's government in matters of health and pharmaceutical policies.[281]

Regional offices

The regional divisions of WHO were created between 1949 and 1952, following the model of the pre-existing Pan American Health Organization,[282] and are based on article 44 of the WHO's constitution, which allowed the WHO to "establish a [single] regional organization to meet the special needs of [each defined] area". Many decisions are made at the regional level, including important discussions over WHO's budget, and in deciding the members of the next assembly, which are designated by the regions.[283]

Each region has a regional committee, which generally meets once a year, normally in the autumn. Representatives attend from each member or associative member in each region, including those states that are not full members. For example, Palestine attends meetings of the Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office. Each region also has a regional office.[283] Each regional office is headed by a director, who is elected by the Regional Committee. The board must approve such appointments, although as of 2004, it had never over-ruled the preference of a regional committee. The exact role of the board in the process has been a subject of debate, but the practical effect has always been small.[283] Since 1999, regional directors serve for a once-renewable five-year term, and typically take their position on 1 February.[284]

Each regional committee of the WHO consists of all the Health Department heads, in all the governments of the countries that constitute the Region. Aside from electing the regional director, the regional committee is also in charge of setting the guidelines for the implementation, within the region, of the health and other policies adopted by the World Health Assembly. The regional committee also serves as a progress review board for the actions of WHO within the Region.[citation needed] The regional director is effectively the head of WHO for his or her region. The RD manages and/or supervises a staff of health and other experts at the regional offices and in specialized centres. The RD is also the direct supervising authority – concomitantly with the WHO Director-General – of all the heads of WHO country offices, known as WHO Representatives, within the region.[citation needed]

The strong position of the regional offices has been criticized in WHO history for undermining its effectiveness and led to unsuccessful attempts to integrate them more strongly within 'One WHO'.[282] Disease specific programmes such as the smallpox eradication programme[285] or the 1980s Global Programme on AIDS[286] were set up with more direct, vertical structures that bypassed the regional offices.

Remove ads

Private funding

In 2024, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation was the organization's major private contributor, funding 10% of its budget.[299]

See also

- Alliance for Healthy Cities, an international alliance

- Global mental health

- Health Sciences Online, virtual learning resources

- Health promotion

- Healthy city

- High 5s Project, a patient safety collaboration

- International Labour Organization

- List of most polluted cities in the world by particulate matter concentration

- Open Learning for Development, virtual learning resources

- Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction- HRP

- The Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health

- Timeline of global health

- United Nations Interagency Task Force on the Prevention and Control of NCDs

- WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

- WHO Guidelines for drinking-water quality

- WHO Pesticide Evaluation Scheme

- WHO SMART guidelines

- Wellbeing economy

- World Hearing Day

Remove ads

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads