Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Fallibilism

Philosophical principle From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

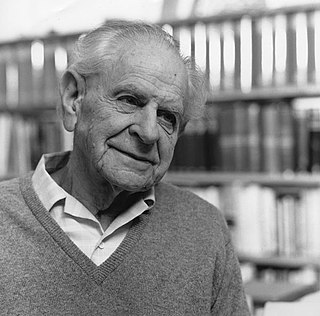

Originally, fallibilism (from Medieval Latin: fallibilis, "liable to error") is the philosophical principle that propositions can be accepted even though they cannot be conclusively proven or justified,[1][2] or that neither knowledge nor belief is certain.[3] The term was coined in the late nineteenth century by the American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce, as a response to foundationalism. Theorists, following Austrian-British philosopher Karl Popper, may also refer to fallibilism as the notion that knowledge might turn out to be false.[4] Furthermore, fallibilism is said to imply corrigibilism, the principle that propositions are open to revision.[5] Fallibilism is often juxtaposed with infallibilism.

Remove ads

Infinite regress and infinite progress

Summarize

Perspective

According to philosopher Scott F. Aikin, fallibilism cannot properly function in the absence of infinite regress.[6] The term, usually attributed to Pyrrhonist philosopher Agrippa, is argued to be the inevitable outcome of all human inquiry, since every proposition requires justification.[7] Infinite regress, also represented within the regress argument, is closely related to the problem of the criterion and is a constituent of the Münchhausen trilemma. Illustrious examples regarding infinite regress are the cosmological argument, turtles all the way down, and the simulation hypothesis. Many philosophers struggle with the metaphysical implications that come along with infinite regress. For this reason, philosophers have gotten creative in their quest to circumvent it.

Somewhere along the seventeenth century, English philosopher Thomas Hobbes set forth the concept of "infinite progress". With this term, Hobbes had captured the human proclivity to strive for perfection.[8] Philosophers like Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Christian Wolff, and Immanuel Kant, would elaborate further on the concept. Kant even went on to speculate that immortal species should hypothetically be able to develop their capacities to perfection.[9]

Already in 350 B.C.E, Greek philosopher Aristotle made a distinction between potential and actual infinities. Based on his discourse, it can be said that actual infinities do not exist, because they are paradoxical. Aristotle deemed it impossible for humans to keep on adding members to finite sets indefinitely. It eventually led him to refute some of Zeno's paradoxes.[10] Other relevant examples of potential infinities include Galileo's paradox and the paradox of Hilbert's hotel. The notion that infinite regress and infinite progress only manifest themselves potentially pertains to fallibilism. According to philosophy professor Elizabeth F. Cooke, fallibilism embraces uncertainty, and infinite regress and infinite progress are not unfortunate limitations on human cognition, but rather necessary antecedents for knowledge acquisition. They allow us to live functional and meaningful lives.[11]

Remove ads

Critical rationalism

Summarize

Perspective

In the mid-twentieth century, several important philosophers began to critique the foundations of logical positivism. In his work The Logic of Scientific Discovery (1934), Karl Popper, the founder of critical rationalism, argued that scientific knowledge grows from falsifying conjectures rather than any inductive principle and that falsifiability is the criterion of a scientific proposition. The claim that all assertions are provisional and thus open to revision in light of new evidence is widely taken for granted in the natural sciences.[12]

Furthermore, Popper defended his critical rationalism as a normative and methodological theory, that explains how objective, and thus mind-independent, knowledge ought to work.[13] Hungarian philosopher Imre Lakatos built upon the theory by rephrasing the problem of demarcation as the problem of normative appraisal. Lakatos' and Popper's aims were alike, that is finding rules that could justify falsifications. However, Lakatos pointed out that critical rationalism only shows how theories can be falsified, but it omits how our belief in critical rationalism can itself be justified. The belief would require an inductively verified principle.[14] When Lakatos urged Popper to admit that the falsification principle cannot be justified without embracing induction, Popper did not succumb.[15] Though, even Lakatos himself had been a critical rationalist in the past, when he took it upon himself to argue against the inductivist illusion that axioms can be justified by the truth of their consequences.[16] In summary, despite Lakatos and Popper picking one stance over the other, both have oscillated between holding a critical attitude towards rationalism as well as fallibilism.[15][17][18][19]

Fallibilism has also been employed by philosopher Willard V. O. Quine to attack, among other things, the distinction between analytic and synthetic statements.[20] British philosopher Susan Haack, following Quine, has argued that the nature of fallibilism is often misunderstood, because people tend to confuse fallible propositions with fallible agents. She claims that logic is revisable, which means that analyticity does not exist and necessity (or a priority) does not extend to logical truths. She hereby opposes the conviction that propositions in logic are infallible, while agents can be fallible.[21] Critical rationalist Hans Albert argues that it is impossible to prove any truth with certainty, not only in logic, but also in mathematics.[22]

Remove ads

Philosophical skepticism

Fallibilism should not be confused with local or global skepticism, which is the view that some or all types of knowledge are unattainable.

But the fallibility of our knowledge — or the thesis that all knowledge is guesswork, though some consists of guesses which have been most severely tested — must not be cited in support of scepticism or relativism. From the fact that we can err, and that a criterion of truth which might save us from error does not exist, it does not follow that the choice between theories is arbitrary, or non-rational: that we cannot learn, or get nearer to the truth: that our knowledge cannot grow.

— Karl Popper

Fallibilism claims that legitimate epistemic justifications can lead to false beliefs, whereas academic skepticism claims that no legitimate epistemic justifications exist (acatalepsy). Fallibilism is also different to epoché, a suspension of judgement, often accredited to Pyrrhonian skepticism.

Criticism

Nearly all philosophers today are fallibilists in some sense of the term.[3] Few would claim that knowledge requires absolute certainty, or deny that scientific claims are revisable, though in the 21st century some philosophers have argued for some version of infallibilist knowledge.[23][24][25] Historically, many Western philosophers from Plato to Saint Augustine to René Descartes have argued that some human beliefs are infallibly known. John Calvin espoused a theological fallibilism towards others' beliefs.[26][27] Plausible candidates for infallible beliefs include logical truths ("Either Jones is a Democrat or Jones is not a Democrat"), immediate appearances ("It seems that I see a patch of blue"), and incorrigible beliefs (i.e., beliefs that are true in virtue of being believed, such as Descartes' "I think, therefore I am"). Many others, however, have taken even these types of beliefs to be fallible.[21]

Remove ads

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads