Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Fat talk

Type of communication on physical appearance From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Fat talk is a type of communication that discusses an individuals' physical appearance, focused on the influence of the excess body fat on weight, shape, style, or fitness of the human body.[1] Researchers have found that fat talk is associated with negative body image,[2] low self-esteem,[3] and eating disorders.[4] Fat talk is most commonly observed in women,[5] individuals with a BMI of over 25, younger individuals, White individuals,[6] and within Western cultures.[7]

The term was coined in 1994 by Nichter and Vuckovic and has become a relevant topic in discussions on body shaming, body image, gender, feminist theory, and social and cultural stereotypes.[8]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

The term fat talk was originally coined by anthropologists Mimi Nichter and Nancy Vuckovic in 1994 from their ethnographic research on middle school girls and their mothers. They found evidence of a ritualized discourse between mothers and their daughters surrounding body image and reports of the daughters feeling pressure to engage in this dialogue with their friends. Fat talk was defined as a method of communication centered on this topic, often involving negative remarks about body weight, fat, fitness, and shape. Nichter and Vuckovic speculated that fat talk has several adaptive functions for girls and women which perpetuates the behavior. These include eliciting reassurance from others, masking other negative emotions that cannot be expressed out right, absolving oneself of guilt for eating something "fattening," creating an ingroup subculture, and managing a social impression.[8]

The origins of fat talk are rooted in long-standing societal norms about body image and gender. Male and female college students view self-degradation and practicing fat talk as normative for female college students.[9] Women and men in the United States of America experience more pressure to engage in fat talk than women and men in the United Kingdom.[10] Familial context also contributes to this culture with the generational transmission of fat talk behaviors.[11]

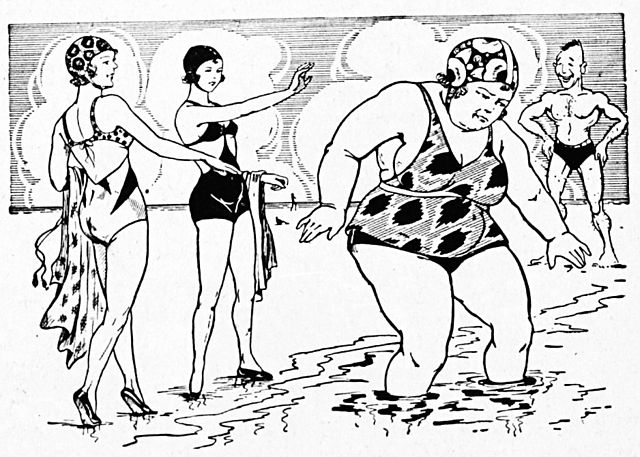

Fat talk provides short-term rewards such as maintaining sociability and eliciting reassurance from others.[8] Nichter and Vuckovic in their seminal work with middle school girls suggested that fat talk only served positive functions; however, later research suggested it is more complicated than that and not always healthy.[8] Women in more objectifying situations (wearing a bathing suit in front of a mirror) who participated in fat talk with another woman (confederate) experienced less negative emotions, while women in less objectifying situations (wearing a sweater in front of a mirror) experienced more negative emotions. This suggests that the context of fat talk matters in terms of how women feel about it.[12] Much of the research on fat talk in the 21st century has documented long-term negative consequences for this behavior. For example, fat talk contributes to body image dissatisfaction,[13] depression,[14] low self-esteem, bulimia nervosa, and self-objectification.[15]

Just as Nichter and Vuckovic witnessed in their formative research on the topic, girls and women engage in fat talk more frequently than boys and men.[8][5] Clinical health psychologist Denise Martz published a monograph that examined the societal and cultural impact of fat talk within a feminist context.[1] Within the body image literature, scientists have known that certain sociocultural factors disproportionately affect women because U.S. women routinely exhibit more body dissatisfaction in comparison to men.[16] Consequently, 81% of women have reported participating in fat talk, and 33% of those women reported participating frequently.[7] These statistics increase when observing college women populations, with 93% of them admitting to fat talk.[17] Men do participate in fat talk,[18] but their conversations tend to focus more on muscle tone and strength, as well as body fat.[19]

Remove ads

Characteristics

One of the most common forms of fat talk includes negative self-talk, where individuals express self-deprecating comments about one's own body. Remarks such as "I feel so fat today", "I'm so fat",[8] "All of my weight goes to my thighs and my butt",[20] "My thighs look huge in these shorts",[21] or "I look horrible in this shirt".[22] These comments reflect feelings of dissatisfaction with one's physical appearance.

Another prevalent form of fat talk is social comparison, where individuals compare their bodies to others. Examples include, "If you're fat, then I'm humongous",[17] "At least you can wear a regular bathing suit to the pool",[23] or, "No you're not, I'm the one who is fat",[14] creating a hierarchy based on body weight or shape.

Fat talk frequently centers around weight loss and dieting. In this form, individuals engage in conversations that focus on dieting, exercise, the desire to lose weight, or the desire to be thin. Examples include, "I really need to start working out again",[24] "I should not be eating fattening foods",[25] or "I'm not in shape".[26]

Remove ads

Correlates of fat talk

Summarize

Perspective

Psychological correlates

Fat talk is a significant predictor of body dissatisfaction, depression, and mental health issues.[27] It is also associated with body-related cognitive distortion, disordered eating, low self-esteem,[3][28] and body shame.[29]

Women with diagnosed eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder engage in fat talk more than women without diagnosed eating disorders.[30] Pregnant women who engage in fat talk exhibit more anxiety disorders than pregnant women who do not engage in fat talk.[31]

Social correlates

Individuals reciprocate fat talk in order to maintain sociability.[32][33] An example of this would be a friend who says "I feel so fat today, look at how my belly is sticking out." The friend who is hearing this then feels compelled to tell her, "You are not fat and your belly is fine. I'm the one with the huge thighs!" This continues the fat talk cycle and maintains social pressures such as body dissatisfaction normalization, thin-ideal internalization, peer pressure, and external validation.[1][17]

Because of social comparison and pressures to be thin, women who engage in fat talk with a woman thinner than themselves experience higher levels of body dissatisfaction.[34][35] Women who more strongly internalize the thin ideal are more likely to engage in fat talk and experience body dissatisfaction and body shame.[36] As women's concerns about their body image are more pronounced, their likelihood of engaging in fat talk is also higher.[23]

Fat talk can be influenced by the norms of specific social contexts. Women engage in fat talk more when they are in a female-dyad situation that demonstrates fat talk norms, but they fat talk less when that same situation demonstrates anti-fat talk norms. Exposure to fat talk is associated with certain correlates of disordered eating (thin-ideal internalization, body dissatisfaction, and negative affect) compared to those exposed to neutral or positive body talk.[37] Experimental exposure to others engaging in fat talk, compared to a neutral topic, results in increased negative affect, body dissatisfaction, and fat phobia.[38]

Child-directed fat talk involves parents making negative comments about their weight in front of their children. Child-directed fat talk is strongly associated with disordered eating behaviors such as binge eating, overeating, secretive eating, and higher rates of overweight and obesity in children.[39]

In heterosexual relationships, women and men feel comfortable engaging in fat talk with each other.[40] Men perceive women engaging in high levels of fat talk compared to self-accepting talk to have poorer perceived mental health .[41] Women and men perceive vignettes of women who excessively participate in fat talk compared to vignettes of women who minimally fat talk to have lower relationship and sexual satisfaction. Relationship and sexual satisfaction are perceived to be lower within romantic heterosexual relationships where women excessively fat talk.[42]

Remove ads

Fat talk and feminism

Summarize

Perspective

Feminist theory and language have been studied in relation to fat talk. Feminists argue that participating in fat talk reinforces unattainable standards of beauty and perpetuates discriminatory gender norms.[1] Fat talk is accepted among women as a way to bond socially, especially in young girls. Young girls have constant exposure to products, television, and social media that demonstrate gender roles, misogyny, dieting, and other concepts that influence fat talk conversations. As a feminist issue, these social-cultural forces tend to maintain body image issues and contribute to eating disorders in girls and women.[1]

Women expressed greater likeability towards vignettes of women expressing feminist-inspired language that challenges fat talk in comparison to vignettes of women expressing fat talk language.[43] Women who self-identify as feminists are more likely to critique fat talk, and are less likely to engage in fat talk. Instead, feminist-identifying women are more likely to offer positive appearance affirmations in response to fat talk, suggesting that feminist theory and language is a potential method to combat fat talk and reduce its occurrences and negative correlates.[44] Further, when engaging in feminist-inspired dialogue, women experience less negative affect compared to women participating in fat talk.[20]

Remove ads

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads