Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

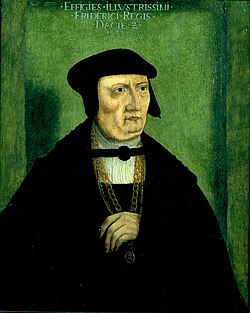

Frederick I of Denmark

King of Denmark (1523–1533) and Norway (1524–1533) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Frederick I (Danish and Norwegian: Frederik; German: Friedrich; Swedish: Fredrik; 7 October 1471 – 10 April 1533) was King of Denmark and Norway from 1523 and 1524, respectively, until his death in 1533, and earlier co-duke Duke of Schleswig and Holstein.

A member of the House of Oldenburg, he was the youngest son of King Christian I and Dorothea of Brandenburg. Not originally destined for the throne, he received joint rule in Schleswig and Holstein on reaching his majority in 1490 and resided chiefly at Gottorf Castle.[3]

Frederick declined the Danish crown on the death of his brother King Hans in 1513 but accepted election in 1523 after opposition to Hans’s son, Christian II. With the backing of Lübeck and North German allies, he prevailed in the ensuing war (1523–1524). His election, arranged by the Council of the Realm, compelled him to accept what is regarded as the most restrictive coronation charter (Danish: håndfæstning) ever imposed on a Danish monarch.[4][5][6] He recognized Gustav Vasa as king of Sweden, abandoning efforts to revive the Kalmar Union, though the two cooperated against Christian II.[7] In Norway, where he neither travelled nor was crowned, he was styled “elected king”, but acknowledged by the Council in 1524.[8]

His reign was dominated by the recurring threat of Christian II’s restoration, who enjoyed the active support of Emperor Charles V. A rising in Blekinge in 1525 led by Christian’s adherent Søren Norby was suppressed by Johan Rantzau, and Christian’s attempt to return via Norway in 1531 achieved initial gains but failed to secure the realm.[9] During the ensuing negotiations in 1532, he was seized and remained in captivity thereafter. Frederick largely governed from Gottorf and delegated day-to-day administration to leading councillors, notably the Steward of the Realm, Mogens Gøye.[10] In foreign policy, he aligned himself with the two leading Protestant powers, Hesse and Saxony, while refraining from joining the Schmalkaldic League.[11][7]

Although oficially a Roman Catholic, Frederick showed sympathy for the Protestant movement, permitting Lutheran preaching and extending protection to reformers such as Hans Tausen, whom he employed as chaplain. He used the confessional divide to balance ecclesiastical and noble interests.[12][7] His reign is widely seen as an interlude of stability in the otherwise chaotic religious upheaval that characterised the period; the equilibrium he upheld dissolved upon his death.[13]

Frederick died at Gottorp in 1533. He was the last Catholic monarch to reign over Denmark and Norway, and his death precipitated the Count’s Feud (1534–1536), a succession war that ended with the accession of his son Christian III and the establishment of Lutheranism as the state religion in Denmark–Norway. Frederick's reign also began the enduring tradition of calling kings of Denmark alternately by the names Christian and Frederick.[14]

Remove ads

Background

Frederick was the younger son of the first Oldenburg King Christian I of Denmark, Norway and Sweden (1426–81) and of Dorothea of Brandenburg (1430–95). Soon after the death of his father, the underage Frederick was elected co-Duke of Schleswig and Holstein in 1482, the other co-duke being his elder brother, King John of Denmark. In 1490 at Frederick's majority, both duchies were divided between the brothers.[15]

In 1500, he had convinced his brother King John to conquer Dithmarschen. A great army was called from not only the duchies, but with additions from all of the Kalmar Union for which his brother briefly was king. In addition, numerous German mercenaries took part. The expedition failed miserably, however, in the Battle of Hemmingstedt, where one-third of all knights of Schleswig and Holstein lost their lives.[16]

Remove ads

Reign

Summarize

Perspective

When his brother, King John died, a group of Jutish nobles had offered Frederick the throne as early as 1513, but he had declined, rightly believing that the majority of the Danish nobility would be loyal to his nephew Christian II.[17]

Rise to power and accession

In late 1522, a group of Jutland nobles and bishops dissatisfied with Christian II’s burgher-friendly policies opened secret contacts with Duke Frederick. In December, Mogens Munk approached him at Gottorf to test his willingness to accept election, and on 25 January 1523 the uprising was proclaimed at the Viborg Landsting, led by Munk and Tyge Krabbe. Munk then offered Frederick the crown at Husum, and he accepted, quickly concluded an alliance with Lübeck, and declared war on Christian II. He appointed Johan Rantzau as military commander, who in March 1523 crossed the frontier with a Holstein force and joined the Jutland rebels at Kolding. On 26 March, Frederick was acclaimed king at the Viborg Landsting, and the following week (on 2 April), Christian II fled to the Low Countries with the queen.[18]

Sweden simultaneously severed the last union ties when a Riksdag proclaimed Gustav Eriksson Vasa king on 6 June 1523. This effectively ended the Kalmar Union. Meanwhile, Frederick’s forces advanced across Funen to Zealand and Copenhagen was invested on 10 June. At Roskilde in August 1523 the haandfæstning was adopted, restoring noble and clerical privileges curtailed under Christian II. Norway’s council submitted on 29 December 1523, and after an eight-month siege Copenhagen capitulated to Rantzau on 6 January 1524, ending Frederick’s campaign.[8]

He was elected king of Norway in 1524. It is not certain that Frederick ever learned to speak Danish. After becoming king, he continued spending most of his time at Gottorp, a castle and estate in the city of Schleswig.[17]

Early struggles and later reign

In 1524 and 1525, Frederick had to suppress revolts among the peasants in Agder, Jutland and Scania who demanded the restoration of Christian II. The high point of the rebellion came in 1525 when Søren Norby, the governor (statholder) of Gotland, invaded Blekinge in an attempt to restore Christian II to power. He raised 8000 men who besieged Kärnan (Helsingborgs slott), a castle in Helsingborg. Frederick's general, Johann Rantzau, moved his army to Scania and defeated the peasants soundly in April and May 1525.[19]

Frederick played a central role in the spread of Lutheran teachings throughout Denmark. In his coronation charter, he was made the solemn protector (værner) of the Catholic Church in Denmark. In that role, he asserted his right to select bishops for the Catholic dioceses in the country. Christian II had been intolerant of Protestant teaching, but Frederick took a more opportunist approach. For example, he ordered that Catholics and Lutherans share the same churches and encouraged the first publication of the Bible in the Danish language. In 1526, when Lutheran Reformer Hans Tausen was threatened with arrest and trial for heresy, Frederick appointed him his personal chaplain to give him immunity.[20]

Starting in 1527, Frederick authorized the closure of Franciscan houses and monasteries in 28 Danish cities. He used the popular anti-establishment feelings that ran against some persons of the Catholic hierarchy and nobility of Denmark as well as keen propaganda to decrease the power of bishops and Catholic nobles.[21]

During his reign, Frederick was skillful enough to prevent all-out warfare between Catholics and Protestants. In 1532, he succeeded in capturing Christian II who had tried to invade Norway, and to make himself king of the country. Frederick died on 10 April 1533 in Gottorp, at the age of 61, and was buried in Schleswig Cathedral. Upon Frederick's death, tensions between Catholics and Protestants rose to a fever pitch which would result in the Count's Feud (Grevens Fejde).[22]

Foreign and dynastic policy

Frederick’s external policy was shaped by the civil and confessional pressures of his reign, domestic risings, and the continuing threat posed by the deposed Christian II. While remaining formally Catholic, he protected the Lutheran movement at home and pursued a cautious, balance-of-power posture abroad aimed at limiting Habsburg leverage and preventing Christian II’s restoration.[23]

Within the Holy Roman Empire he cultivated the leading evangelical princes. In April 1528 he concluded an alliance with Hesse and received Landgrave Philip at Gottorp, and he maintained close relations with the Ernestine Saxon court. After the formation of the Schmalkaldic League in 1531, he coordinated with its members but declined formal adhesion. In 1532 he entered a separate agreement with Protestant princes without binding military commitments. Dynastically, he strengthened Denmark–Norway’s Baltic position through the marriage of his daughter Dorothea to Albert, duke of Prussia, in 1526, creating a durable axis of interest across the southern Baltic.[23]

In Scandinavia his priority was a stable modus vivendi with Sweden. By the Treaty of Malmö (1524) Denmark–Norway recognized Gustav Vasa as king of Sweden, formally ending the Kalmar union era. Thereafter Copenhagen and Stockholm could act in parallel where interests coincided, notably in deterring attempts to restore Christian II.[23]

Frederick’s diplomatic endeavours predated his accession. As duke he had already sought a counterweight to Habsburg influence, including a treaty association with France at Amboise in 1518.[23] Following the imprisonment of Christian II, Frederick reached a diplomatic settlement with Charles V, and maintained peace until his death.[24]

He married firstly in 1502 Anna of Brandenburg, daughter of John Cicero, Elector of Brandenburg and Margaret of Thuringia. She was the sister of Joachim I Nestor, Elector of Brandenburg, and the alliance with the House of Hohenzollern was arranged by and conformed to the dynastic policy pursued by King Hans, which strengented Denmark's position among the imperial electors.[7] He married secondly in 1514 Sophie of Pomerania, daughter of Bogislaw "the Great", Duke of Pomerania and Anna Jagiellon, daughter of Casimir IV Jagiellon. The union with the House of Griffin also linked Frederick maternally to the Jagiellonian dynasty.[25] The children of Frederick married into the houses of Mecklenburg (both Mecklenburg-Güstrow, Mecklenburg-Schwerin and Mecklenburg-Gadebusch), Ascania (Saxe-Lauenburg), Hohenzollern and Hesse.

Remove ads

Character and portrayal

Summarize

Perspective

Contemporary testimony from Frederick himself is scant, and even such basics as whether he spoke Danish remain uncertain. The king’s German chancellor Wolfgang Utenhof praised him as a conscientious, prudent and humane ruler, though later historians have cautioned that Utenhof’s encomium may reflect his disaffection with Frederick’s successor, Christian III. The councillor Johan Friis, writing in 1527, offers a less reverential glimpse: he referred to Frederick irreverently as “Abraham with the grey beard,” complained of his parsimony and avarice, and described his irritability when payment terms fell due.[26]

Later narratives often stress how constrained Frederick’s kingship was by aristocratic power. Danish historian Benito Scocozza memorably styled him "prisoner of the Nobility" (Danish: adelens fange), a judgement commonly linked to the exceptionally restrictive coronation charter he accepted in 1523 and to his reliance on the Rigsråd in day-to-day governance.[4] The late-sixteenth-century historian Arild Huitfeldt (1596) portrayed him as “an old hen reluctant to leave his nest in Gottorp".[4]

Modern scholars emphasise a pragmatic, peace-preferring cast of mind. Peder Christoffersen describes Frederick as “shrewd, cautious, [and] socially conservative,” a king who preferred peace to point-scoring and who, in religious matters, supported Luther’s teaching to a degree but “not enough to stake his monarchy on the cause.” Christoffersen is also unsparing about appearance, depicting Frederick as stout, with a prominent nose, full cheeks and thin lips.[27] Concerning finances, Rikke Agnete Olsen argues that Frederick inherited his mother Dorothea’s economic sense “bordering on stinginess”.[7]

Family and children

Summarize

Perspective

On 10 April 1502, Frederick married Anna of Brandenburg (1487–1514), the daughter of John Cicero, Elector of Brandenburg and Margaret of Thuringia. The couple had two children:

- Christian III, King of Denmark and Norway (12 August 1503 – 1 January 1559)[28]

- Dorothea of Denmark (1 August 1504 – 11 April 1547),[29] married 1 July 1526 to Albert, Duke of Prussia.

Frederick's wife Anna died on 5 May 1514, 26 years old. Four years later on 9 October 1518 at Kiel, Frederick married Sophie of Pomerania (20 years old; 1498–1568), a daughter of Bogislaw "the Great", Duke of Pomerania. Sophie and Frederick had six children:

- John, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Haderslev (28 June 1521 – 2 October 1580)[30]

- Elizabeth of Denmark (14 October 1524 – 15 October 1586),[31] married:

- on 26 August 1543 to Magnus III of Mecklenburg-Schwerin.

- on 14 February 1556 to Ulrich III, Duke of Mecklenburg-Güstrow.

- Adolf of Denmark, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp (25 January 1526 – 1 October 1586)[32]

- Anna of Denmark (1527 – 4 June 1535)

- Dorothea of Denmark (1528 – 11 November 1575),[33] married on 27 October 1573 to Christopher, Duke of Mecklenburg-Gadebusch.

- Frederick of Denmark (13 April 1532 – 27 October 1556), Prince-Bishop of Hildesheim and Bishop of Schleswig.

He is the common ancestor of all surviving branches of the House of Oldenburg.

Remove ads

Ancestors

Remove ads

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads