Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

French Republicans under the July Monarchy

Political event From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Although the Three Glorious Days of July 1830 involved the participation of various political groups, including Republicans, the outcome led to the establishment of a second constitutional monarchy under Louis-Philippe. The July Revolution ultimately benefited the liberal bourgeoisie, who were better positioned and organized to form a new regime and who generally opposed the creation of a republic. As a result, Republican opposition to the new constitutional monarchy continued.

This article may incorporate text from a large language model. (September 2025) |

Remove ads

Republicans at the dawn of the July Monarchy

Summarize

Perspective

Disappointment with the new regime

Following the July Revolution of 1830, known as the Three Glorious Days, France experienced a surge in political activity. New political societies were established, and organizations active during the Bourbon Restoration were revived. Notable among them were the Society of the Friends of the People, the Society of Human Rights, and the Society of the Constitution. The Society of the Friends of the People became particularly active, opposing the accession of King Louis-Philippe I and advocating for a republican form of government.[1] Universities formed leagues to promote literacy, and on 21 September 1830, a public gathering commemorated the Four Sergeants of La Rochelle, who had been executed in 1822.[2] The July Revolution also influenced events beyond France, including the Belgian Revolution against Dutch rule, uprisings in Poland against Russian authority, and movements linked to Italian unification. While absolutist governments viewed the developments in France with apprehension, liberal groups in Europe and the United States—where preparations were underway to commemorate the Treaty of Paris (1783), initially received the new regime with cautious approval. However, early optimism diminished in the following months.[3]

Expectations that the July Monarchy would embody republican ideals, as described by Adolphe Thiers as a "republic disguised as a monarchy," quickly faded. While the government distributed "July medals" to participants in the revolution, these symbolic actions did not prevent growing criticism.[4] In September 1830, the new Minister of the Interior, François Guizot, initiated legal action against individuals accused of "inciting hatred against the king," including some who had received medals.[4] Republicans criticized the 1830-elected chamber as lacking legitimacy, and the Society of the Friends of the People rejected it as inconsistent with revolutionary objectives.[5] Although some reforms were enacted, such as the abolition of hereditary peerage, the chamber also passed restrictive measures reminiscent of those under the Restoration, including press censorship and limitations on political associations. These policies led to protests, including student strikes.[6] At Benjamin Constant's funeral in 1830, Republican leader Ulysse Trélat declared the July Monarchy an adversary, signaling their commitment to continue the struggle.[7]

La Fayette, who had played a significant role in supporting Louis-Philippe's accession to the throne, later expressed dissatisfaction with the direction of the regime. In December 1830, he resigned as commander of the National Guard, reportedly under pressure from the government.[8] The resignation of Jacques-Charles Dupont de l'Eure as Minister of Justice further highlighted growing divisions between Orléanists and Republicans.[9] In response, figures such as Armand Marrast and Cavaignac, with the support of the newspaper Le National and the Aide-toi, le ciel t'aidera society, established new republican associations aimed at countering potential legitimist threats and reinforcing republican influence.[9] The Republican movement was divided over strategy. Leaders such as Ulysse Trélat, Étienne Cabet, Philippe Buchez, Marrast, and Garnier-Pagès supported political engagement, while others, including Cavaignac, Jules Bastide, and Étienne Arago supported insurrection.[10] Republican mobilization was evident during the trial of Charles X's ministers. When the court sentenced them to life imprisonment rather than execution, as some Republicans had anticipated, unrest broke out, though it was quickly suppressed.[11] Additional incidents, such as the sacking of the church of Saint-Germain l'Auxerrois during anti-Carlist demonstrations, contributed to political instability and the eventual fall of the Laffitte ministry. It was succeeded by the government led by Casimir Pierre Périer.[12]

Casimir Périer vs. the Republicans

Casimir Périer summarized his political stance with the phrase: "At home, order without sacrifice to liberty; abroad, peace without cost to honor." His position toward Republican movements during the early July Monarchy soon became apparent. Although Périer initially supported moderate reforms—such as changes to the electoral system—he opposed more radical proposals, including the remuneration of deputies, a measure promoted by Republicans to ensure broader participation in politics. At the time, deputies were not salaried, which tended to favor wealthier individuals or those dependent on government patronage. Critics argued this allowed the executive to influence modestly resourced representatives by offering civil service appointments. One illustrative case was Paul Dubois, a former Carbonari and director of Le Globe, who accepted a high-level administrative role, signaling the regime’s strategy of integrating or sidelining dissident voices.[13]

The government also implemented a broader administrative purge, removing officials affiliated with Republican associations formed after the 1830 July Revolution. This included the dismissal of local officeholders—such as mayors, judges, and prosecutors—who were perceived as sympathetic to Republicanism. Odilon Barrot and Alexandre de Laborde resigned from their respective administrative posts: Barrot from the prefecture of the Seine and Laborde from the Paris municipal council. Eugène Cavaignac, then a junior officer, was reportedly suspended after stating he would not take arms against Republican demonstrators. These actions were part of a wider strategy by the parti de la résistance to consolidate power and marginalize Republican activism.[14]

In April 1831, Périer instructed public prosecutors to take strong legal action against Republican press outlets, initiating a series of prosecutions against editors and journalists. According to historian Georges Weill, newspapers such as La Tribune,[15] faced frequent legal challenges. The government further targeted prominent Republican figures in what became known as the "Trial of the Nineteen", accusing activists, including Cavaignac, Guinard, Marrast, Trélat, and Bastide, of inciting unrest during the trial of Charles X’s ministers. However, the defense mounted by Republican lawyers, including Louis Michel, led to the acquittal of all nineteen defendants, an outcome that was met with public applause in the courtroom.[16]

The Canut revolt in Lyon in November 1831 underscored growing social tensions and energized segments of the Republican movement advocating for workers' rights. Following the July Revolution of 1830, Republicans organized educational initiatives that challenged the traditional monopoly of the state and Church over schooling. Jacques-Charles Dupont de l'Eure founded the Association pour l'instruction gratuite du peuple (Association for the Free Education of the People), and Lazare Carnot revived an earlier educational society.[17] In response to these initiatives, François Guizot, Minister of Public Instruction, passed a major education reform law in 1833 that aimed to expand primary education across France.[17] Meanwhile, Republican intellectuals began producing literature aimed at working-class readers as early as 1831, partly influenced by British religious and social reform movements and supported initially by Saint-Simonians.[18] However, ideological tensions emerged between Republicans and Saint-Simonians, particularly over the latter’s limited interest in establishing a republican regime.[19][20] In 1831, Étienne Cabet published Péril de la situation présente in support of the Canuts, and in 1833 he co-founded Le Populaire, a newspaper focused on workers' issues, with Philippe Buchez. Both figures became central to the emergent socialist-republican discourse.[21]

The perceived momentum of the Republican movement led Périer to intensify government efforts to suppress it. In January 1832, a second wave of political trials—referred to as the "Trial of the Fifteen"—targeted members of the Société des Amis du Peuple (Society of the Friends of the People).[22] As with the previous year's trial, the courtroom became a platform for Republican rhetoric. Ulysse Trélat and particularly François-Vincent Raspail used the occasion to denounce economic inequality, with Raspail asserting that two-thirds of France’s 32 million inhabitants were suffering from hunger.[23] He was sentenced to two years in prison and fined 1,000 francs, but his courtroom speech resonated widely, gaining attention in Republican press outlets, the Chamber of Deputies, and student circles.[24] Although the government managed to secure convictions, the Republican movement was bolstered by public sympathy and widespread criticism of Périer's repressive policies. His death from cholera in May 1832 was viewed by many Republicans as a potential turning point for a more conciliatory or reformist direction in the monarchy's governance.[25]

Remove ads

Direct opposition to the Orléanists

Summarize

Perspective

Insurrection of 1832

On May 22, 1832, thirty-nine opposition deputies, including Republicans and liberals dissatisfied with the July Monarchy, met at the residence of banker Jacques Laffitte and issued the Compte rendu des 39 (Report of the 39). Intended to articulate the objectives of the left-wing opposition, the document primarily criticized the July Monarchy, characterizing the July Revolution of 1830 as a "wasted effort" and advocating for a republic as the only legitimate form of government.[26] Signed on May 28, the report contributed to the growing confidence of Republican movements. The death of the young Republican Évariste Galois in a duel on May 31 attracted public attention and became a symbolic event for opposition groups. His funeral on June 2 reportedly served as a gathering point for Republicans, where the possibility of future uprisings was discussed.[27] At the same time, ultra-royalist activity was resurging in parts of western France, including attempts to revive the Chouannerie. The death of General Jean Maximilien Lamarque on June 1, during a cholera epidemic, further galvanized Republican sentiment. Known for his opposition to the July Monarchy and support for liberal and nationalist causes, Lamarque was widely admired by Republicans and Bonapartists alike. A public funeral procession was organized in Paris for June 5 to honor him and to commemorate Polish nationalists killed during the November Uprising against Russian rule.[28]

On June 5, 1832, the funeral procession for Lamarque in Paris escalated into a violent confrontation when insurgents attempted to spark a Republican uprising—an event later known as the June Rebellion. The revolt received limited support from segments of the National Guard but failed to gain broader momentum.[26] King Louis-Philippe responded swiftly by deploying government troops to suppress the insurrection. The rebellion began to falter as several opposition leaders, including those involved in the Compte rendu des Trente-Neuf, shifted from advocating for a republic to calling for constitutional reforms within the monarchy. Key figures such as General Lafayette distanced themselves from the uprising, while others were arrested or withdrew from public activity.[29]

By June 6, government forces had quelled the rebellion. The monarchy, refusing to make concessions to moderate opposition figures such as Odilon Barrot, reasserted its control.[29] The suppression of the rebellion angered many Republicans, including Alexandre Auguste Ledru-Rollin, who criticized what he saw as the hypocrisy of a regime that had itself come to power through revolution now violently repressing popular protest.[30] The exact origins and coordination of the June Rebellion remain debated. Some contemporary sources and police reports suggest involvement by members of the Society of the Rights of Man (Société des Droits de l'Homme), including Éléonore-Louis Godefroi Cavaignac, who may have acted independently.[31] Other accounts cite lesser-known associations such as the Société Gauloise de Deschapelles as possible organizers, though direct evidence remains limited.[32]

Arrival of Thiers

Following the June Rebellion of 1832, the French government, facing significant unrest, dissolved the Society of the Friends of the People after a trial in which Éléonore-Louis Godefroi Cavaignac criticized Article 291 of the Penal Code for restricting freedom of association, arguing that such freedoms were essential for addressing social issues.[33] In October 1832, Adolphe Thiers was appointed Minister of the Interior and intensified efforts to suppress Republican activity. Drawing on his experience with clandestine networks during the Bourbon Restoration, Thiers launched over 300 legal actions against Republican publications, notably targeting La Tribune, edited by Armand Marrast, and Le Populaire, edited by Étienne Cabet, which had a circulation of 27,000.[6] The government imposed fines totaling over 215,000 francs on the Republican press—a considerable sum at the time.[34] In response, Republicans established associations to defend press freedom, asserting that the press, rather than the limited electorate, best represented the population. These associations called for public support to help pay the fines.[35]

The Republican opposition, supported by the newly formed Comité d'Action Central de Paris, organized into five specialized committees to coordinate its efforts. The Inquiry Committee, led by Étienne Cabet, Armand Marrast, and Joseph Guinard, examined government restrictions on press freedom. The Legal Defense Committee, headed by Jacques-Charles Dupont de l'Eure, managed court defenses. The Relief Committee, under Louis-Marie de Lahaye Cormenin, raised funds for imprisoned Republicans and their families. The Legislation Committee, led by Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, Armand Carrel, and Étienne Joseph Louis Garnier-Pagès, focused on legislative matters. The Central Press Committee, directed by Voyer d’Argenson and Éléonore-Louis Godefroi Cavaignac, coordinated Republican press activities.[36] Supported by the Aide-toi, le ciel t'aidera society and the Society for the Rights of Man, the successor to the Society of the Friends of the People, the committee appointed regional coordinators—Cabet for the East, Ulysse Trélat for the South, Garnier-Pagès for the North, and Berrier-Fontaine for the West—to strengthen provincial republican newspapers.[37] These efforts led to the revival of several regional publications, including one in Puy-de-Dôme by Trélat, Le Patriote de Juillet in Toulouse by Jacques Joly, and Le Patriote de la Côte-d’Or by Cabet.[37] In November 1833, workers closely aligned with Republican associations organized a strike, which Republican leaders supported. Thiers, with backing from deputies including François Guizot and Victor de Broglie, allowed the strike to collapse due to lack of provisions, forcing workers to return to their jobs. The event prompted an escalation of government repression against Republicans in 1834.[38]

1834

In early 1834, Adolphe Thiers, serving as Minister of the Interior, introduced a law requiring peddlers to obtain state authorization to distribute printed materials. This measure curtailed a traditional means of disseminating information among France’s largely illiterate population, many of whom relied on peddlers to read newspapers aloud and circulate almanacs.[39] The restriction provoked widespread opposition, particularly in Lyon, where silk workers (canuts) launched a month-long strike, and in Nantes, where Republican associations demanded universal suffrage for the election of deputies.[40] On February 22, 1834, a new law was enacted banning unauthorized associations, with exceptions only for artistic, religious, or literary groups. The legislation targeted Republican clubs and workers’ mutual aid societies.[40] Its passage sparked protests across France, where demonstrators sang La Marseillaise and chanted Republican slogans. Outside of Orléanist circles, the law was widely condemned as excessively repressive.[40] Thiers’s actions were perceived by many as an attempt to provoke a Republican backlash that could serve as justification for harsher repression. Republican leaders were divided: some called for direct resistance, while others urged caution to avoid being drawn into confrontation. The movement's cohesion was further undermined by the fragmentation of local associations and lack of centralized coordination.[41]

On April 9, 1834, the trial of canut leaders involved in the February unrest in Lyon began, prompting around 6,000 demonstrators to gather in support of the accused.[42] Tensions escalated when soldiers fired on an unarmed crowd during a speech by defense attorney Jules Favre, contributing to the outbreak of violent confrontations in Paris, including the Massacre of the Rue Transnonain, where troops killed residents of a working-class building suspected of harboring insurgents.[43] The incident triggered a wave of protests across the country. Although plans for uprisings in western France and the Jura were abandoned, the government launched a broad crackdown, arresting over 2,000 suspected Republicans and conducting extensive house searches nationwide.[44] The Republican press faced intensified censorship. Armand Marrast, editor of La Tribune, was imprisoned at Sainte-Pélagie, whiled Armand Carrel continued to publish Le National before going into exile in England.[45] The 1834 legislative elections produced mixed outcomes for Republicans: although they lost some seats, prominent liberal figures such as Jacques Laffitte and Odilon Barrot were elected. In October 1834, the Chamber of Peers was designated as a high court to try the approximately 2,000 arrested Republicans in what historian Pierre Larousse later referred to as the "Monster Trial."[44][46]

Remove ads

Trial and the period of decline

Summarize

Perspective

Initiatives

By late 1834, the Republican movement was in decline due to weak leadership and ineffective communication. In May 1835, the trial of the April 1834 insurgents, known as the "Monster Trial," began, with Republicans attempting to use it for propaganda purposes.[47] However, their efforts largely failed as they were branded Jacobins, alienating the bourgeoisie, who took measures to block Republican advances.[47] The court handed down relatively lenient sentences to avoid further unrest. Of the approximately 2,000 defendants, 121 were convicted, with 43 tried in absentia. Most received multi-year prison terms; some were acquitted or deported. No death sentences were imposed, in part to avoid creating Republican martyrs.[47]

Following the "Monster Trial," the Republican movement weakened further as the bourgeoisie distanced itself and public opinion increasingly portrayed Republicans as agitators. On July 28, 1835, during a military review marking the anniversary of the July Monarchy, an explosive device detonated at 50 Boulevard du Temple despite prior warnings of potential assassination attempts.[47] Although the royal family escaped unharmed, General Mortier and seventeen others were killed. The attackers—Giuseppe Marco Fieschi and two accomplices linked to the Society for the Rights of Man, were arrested, tried, sentenced to death, and executed on February 19, 1836.[48] The attack dealt a severe blow to the Republican movement’s public standing.[47]

Reorganization

During the July Monarchy, the Republican movement diversified, with socialist ideologies gaining prominence. Thinkers such as Louis Blanc and Louis Auguste Blanqui influenced these ideas, though their approaches differed.[49] Blanc advocated social democracy and universal male suffrage, while Blanqui rejected electoral politics in favor of land collectivization. Despite their shared goal of overthrowing the July Monarchy, Republicans and socialists remained divided, with many Republicans opposing the idea of a social republic.[50] By the 1840s, internal divisions among socialists, neo-communists, and moderates weakened the Republican movement. Although secret societies multiplied, their overall impact was limited.[3] Central disputes concerned the right to work and government intervention in social issues, with moderates opposing state involvement, while radicals—drawing inspiration from the Canut revolts—advocated linking governmental authority with social reform.[51]

After the banning of Armand Marrast’s La Tribune des départements, new Republican publications emerged, including Louis Blanc’s La Revue du Progrès in 1839 and La Réforme in 1843, founded by Alexandre Auguste Ledru-Rollin, Louis-Eugène Cavaignac, and Victor Schœlcher. These outlets championed male suffrage and freedom of association, rights curtailed by the April 10, 1834 law. Republicans also contributed to Le National, associated with Adolphe Thiers, to promote republican ideals among the petite bourgeoisie.[52]

In 1839, a Republican insurrection led by radicals Louis Auguste Blanqui and Armand Barbès and organized by the Jacobin-inspired Society of the Seasons, attempted to overthrow the July Monarchy.[49] The poorly coordinated revolt failed to seize Paris’s city hall, and its leaders were quickly arrested.[53] In 1841, Republicans, along with legitimists, supported rural riots opposing Finance Minister Georges Humann’s plan to reassess the portes et fenêtres tax, accusing François Guizot’s government of seeking to reinstate Ancien Régime taxation and increase the tax burden.[54]

During the 1839 legislative elections, several Republican deputies, including Louis-Antoine Garnier-Pagès, François Arago, and Hippolyte Carnot, were elected to the Chamber of Deputies. In subsequent elections, about ten Republicans gained seats. The growing acceptance of Republicans was partly influenced by evolving historiography, with intellectuals such as Jules Michelet and Louis Blanc working to separate the French Revolution from the Reign of Terror.[55]

Remove ads

Republican resurgence

Summarize

Perspective

Actions toward a new revolution

In the late 1830s and early 1840s, France experienced economic hardship caused by poor harvests, the collapse of railroad speculation, and François Guizot’s conservative policies. These factors contributed to the country’s last major famine, sparking food riots and widespread unrest. The government’s commitment to laissez-faire economics and refusal to intervene exacerbated the crisis. Amid growing discontent, Republicans regained political prominence.[56]

Guizot’s government further alienated rural populations through policies such as the 1844 hunting permit requirement, which was seen as undermining rights established since the French Revolution of 1789 and raised fears of a return to Ancien Régime practices. Although the February 1848 insurrection was primarily driven by Parisians, the absence of rural uprisings helped legitimize the new republican regime.[57]

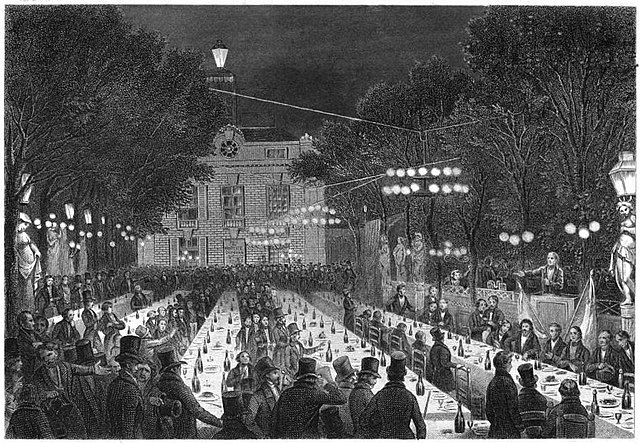

Banquets: A lethal weapon

In early 1847, opposition Republicans and liberals organized political banquets to discuss reforms, initially advocating moderate change within the July Monarchy. The first banquet, held in Paris on July 9, 1847, featured Odilon Barrot addressing 1,200 attendees. The campaign expanded, with about 70 banquets held across cities such as Autun, Dijon, and Toulouse, elevating Republicans above the Dynastic Opposition, which favored reform but remained loyal to the monarchy.[58] Discussions increasingly addressed social issues, including workers’ conditions and, in some cases, socialist ideas. At a Valenciennes banquet, participants toasted “the abolition of misery through labor.” Prominent figures such as Alphonse de Lamartine, Louis Blanc, and Marie, who invoked “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” in Orléans, took part. By January 1848, support for fundamental freedoms had largely replaced loyalty to the monarchy. Republicans used these events to mobilize the petite and middle bourgeoisie, although radicals like Ledru-Rollin opposed bourgeois Orléanist participation, calling for a purely republican revolution.[58]

Revolution

In February 1848, the Guizot government faced mounting opposition. On February 17, conservative deputies proposed moderate reforms, which Guizot rejected. Amid the ongoing banquet campaign, Guizot banned a planned banquet in Paris’s 12th arrondissement on February 21, intensifying Republican resolve. On February 22, about 3,000 demonstrators protested against the July Monarchy and Guizot, marching toward the Chamber of Deputies. Despite King Louis-Philippe’s confidence in his 30,000-strong army, tensions escalated on February 23 when soldiers of the 14th Line Regiment fired on a crowd at Boulevard des Capucines, killing 50 people.[59] This violence fueled further unrest. On February 24, insurgents seized armories, and Louis-Philippe, unwilling to risk further bloodshed, lost control of Paris. Unlike the 1830 Revolution, which resulted in a constitutional monarchy, Republicans took decisive action. As the bourgeoisie sought to form a new government, Republicans stormed the Palais Bourbon and established a provisional government. Alphonse de Lamartine proclaimed the Second Republic, ending the July Monarchy.[59]

Remove ads

Republican ideology under the July Monarchy

Summarize

Perspective

The republican movement in 1830 included not only supporters of the Republic but also socialists, Saint-Simonians, and Bonapartists.

Following the February 1848 Revolution, which established the Second French Republic following over three decades of monarchy, many progressive Orléanists and Legitimistssupported the new republic, welcoming the fall of the July Monarchy. Historian Maurice Agulhon termed them "Republicans of the day after," distinguishing them from "Republicans of the day before," who had long advocated for a republic.[60]

Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte's collaboration with monarchists during the Second Restoration ended the tentative alliance between Bonapartists and Republicans. This shift weakened the Napoleonic legend that had linked Napoleon I to the ideals of the French Revolution.[61]

Following the June 1848 events, the abandonment of a social republic caused a lasting split within the republican movement, dividing democratic-socialists,[62] who supported a social republic, from moderates favoring a conservative republic. This ideological divide persisted into the Third Republic, where radicals and opportunists frequently clashed, particularly over colonial policy.[63][64]

Remove ads

See also

References

Bibliography

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads