Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

List of French monarchs

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

France was ruled by monarchs from the establishment of the kingdom of West Francia in 843 until the end of the Second French Empire in 1870, with several interruptions.

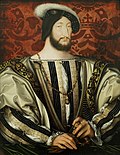

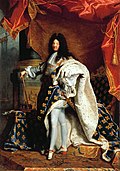

From top; left to right: Robert I, Hugh Capet, Louis IX, Francis I, Henry IV, Louis XIV, Louis XVI, Napoleon I, Napoleon III

Classical French historiography usually regards Clovis I, king of the Franks (r. 507–511), as the first king of France. However, most historians today consider that such a kingdom did not begin until the establishment of West Francia, after the fragmentation of the Carolingian Empire in the 9th century.[1][2]

Remove ads

Titles

Summarize

Perspective

The kings used the title "King of the Franks" (Latin: Rex Francorum) until the late twelfth century; the first to adopt the title of "King of France" (Latin: Rex Franciae; French: roi de France) was Philip II in 1190 (r. 1180–1223), after which the title "King of the Franks" gradually lost ground.[3] However, Francorum Rex continued to be sometimes used, for example by Louis XII in 1499, by Francis I in 1515, and by Henry II in about 1550; it was also used on coins up to the eighteenth century.[4]

During the brief period when the French Constitution of 1791 was in effect (1791–1792) and after the July Revolution in 1830, the style "King of the French" (roi des Français) was used instead of "King of France (and Navarre)". It was a constitutional innovation known as popular monarchy which linked the monarch's title to the French people rather than to the possession of the territory of France.[5]

With the House of Bonaparte, the title "Emperor of the French" (Empereur des Français) was used in 19th-century France, during the first and second French Empires, between 1804 and 1814, again in 1815, and between 1852 and 1870.[6]

From the 14th century down to 1801, the English (and later British) monarch claimed the throne of France, though such claim was purely nominal excepting a short period during the Hundred Years' War when Henry VI of England had control over most of Northern France, including Paris. By 1453, the English had been mostly expelled from France and Henry's claim has since been considered illegitimate; French historiography commonly does not recognize Henry VI of England among the kings of France.

Remove ads

Frankish kings (843–987)

Summarize

Perspective

Carolingian dynasty (843–887)

The Carolingians were a Frankish noble family with origins in the Arnulfing and Pippinid clans of the 7th century AD. The family consolidated its power in the 8th century, eventually making the offices of mayor of the palace and dux et princeps Francorum hereditary and becoming the real powers behind the Merovingian kings. The dynasty is named after one of these mayors of the palace, Charles Martel, whose son Pepin the Short dethroned the Merovingians in 751 and, with the consent of the Papacy and the aristocracy, was crowned King of the Franks.[7] Under Charles the Great (r. 768–814), better known as "Charlemagne", the Frankish kingdom expanded deep into Central Europe, conquering Italy and most of modern Germany. He was also crowned "Emperor of the Romans" by the Pope, a title that was eventually carried on by the German rulers of the Holy Roman Empire.

Charlemagne was succeeded by his son Louis the Pious (r. 814–840), who eventually divided the kingdom between his sons. His death, however, was followed by a three-year-long civil war that ended with the Treaty of Verdun, which divided Francia into three kingdoms, one of which (Middle Francia) was short-lived. Modern France developed from West Francia, while East Francia became the Holy Roman Empire and later Germany. By this time, the eastern and western parts of the land had already developed different languages and cultures.[8][9]

Robertian dynasty (888–898)

Carolingian dynasty (898–922)

Robertian dynasty (922–923)

Bosonid dynasty (923–936)

Carolingian dynasty (936–987)

Remove ads

Capetian dynasty (987–1792)

Summarize

Perspective

The Capetian dynasty is named for Hugh Capet, a Robertian who served as Duke of the Franks and was elected King in 987. Except for the Bonaparte-led Empires, every monarch of France was a male-line descendant of Hugh Capet. The kingship passed through patrilineally from father to son until the 14th century, a period known as Direct Capetian rule. Afterwards, it passed to the House of Valois, a cadet branch that descended from Philip III. The Valois claim was disputed by Edward III, the Plantagenet king of England who claimed himself as the rightful king of France through his French mother Isabella. The two houses fought the Hundred Years' War over the issue, and with Henry VI of England being for a time partially recognized as King of France.

The Valois line died out in the late 16th century, during the French Wars of Religion, to be replaced by the distantly related House of Bourbon, which descended through the Direct Capetian Louis IX. The Bourbons ruled France until deposed in the French Revolution, though they were restored to the throne after the fall of Napoleon. The last Capetian to rule was Louis Philippe I, king of the July Monarchy (1830–1848), a member of the cadet House of Bourbon-Orléans.

House of Capet (987–1328)

The House of Capet are also commonly known as the "Direct Capetians".

House of Valois (1328–1589)

The death of Charles IV started the Hundred Years' War between the House of Valois and the House of Plantagenet, whose claim was taken up by the cadet branch known as the House of Lancaster, over control of the French throne. The Valois claimed the right to the succession by male-only primogeniture through the ancient Salic Law, having the closest all-male line of descent from a recent French king. They were descended from the third son of Philip III, Charles, Count of Valois. The Plantagenets based their claim on being closer to a more recent French king, Edward III of England being a grandson of Philip IV through his mother, Isabella.

The two houses fought the Hundred Years War to enforce their claims. The Valois were ultimately successful, and French historiography counts their leaders as rightful kings. One Plantagenet, Henry VI of England, enjoyed de jure control of the French throne following the Treaty of Troyes, which formed the basis for continued English claims to the throne of France until 1801. The Valois line ruled France until the line became extinct in 1589, in the backdrop of the French Wars of Religion. As Navarre did not have a tradition of male-only primogeniture, the Navarrese monarchy became distinct from the French with Joan II, a daughter of Louis X.

House of Valois-Orléans (1498–1515)

House of Valois-Angoulême (1515–1589)

House of Bourbon (1589–1792)

The Valois line looked strong on the death of Henry II, who left four male heirs. His first son, Francis II, died in his minority. His second son, Charles IX, had no legitimate sons to inherit. Following the premature death of his fourth son Hercule François and the assassination of his third son, the childless Henry III, France was plunged into a succession crisis over which distant cousin of the king would inherit the throne. The best claimant, King Henry III of Navarre, was a Protestant, and thus unacceptable to much of the French nobility.

Ultimately, after winning numerous battles in defence of his claim, Henry converted to Catholicism and was crowned as King Henry IV, founding the House of Bourbon. This marked the second time the thrones of Navarre and France were united under one monarch, as different inheritance laws had caused them to become separated during the events of the Hundred Years Wars. The House of Bourbon was overthrown during the French Revolution and replaced by a short-lived republic.

Remove ads

Long 19th-century (1792–1870)

Summarize

Perspective

The period known as the "long nineteenth century" was a tumultuous time in French politics. The period is generally considered to have begun with the French Revolution, which deposed and then executed Louis XVI. Royalists continued to recognize his son, the putative king Louis XVII, as ruler of France. Louis was under arrest by the government of the Revolution and died in captivity having never ruled. The republican government went through several changes in form and constitution until France was declared an empire, following the ascension of the First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte as Emperor Napoleon I. Napoleon was overthrown twice following military defeats during the Napoleonic Wars.

After the Napoleonic period followed two different royal governments, the Bourbon Restoration, which was ruled successively by two younger brothers of Louis XVI, and the July Monarchy, ruled by Louis Philippe I, a distant cousin who claimed descent from Philippe I, Duke of Orléans, younger brother of Louis XIV. The French Revolution of 1848 brought an end to the monarchy again, instituting a brief Second Republic that lasted four years, before its president declared himself Emperor Napoleon III, who was deposed and replaced by the Third Republic, and ending monarchic rule in France for good.

House of Bonaparte, First French Empire (1804–1814)

House of Bourbon, First Restoration (1814–1815)

House of Bonaparte, Hundred Days (1815)

House of Bourbon, Second Restoration (1815–1830)

House of Bourbon-Orléans, July Monarchy (1830–1848)

The Bourbon Restoration came to an end with the July Revolution of 1830, which deposed Charles X and replaced him with Louis Philippe I, a distant cousin with more liberal politics. Charles X's son Louis signed a document renouncing his own right to the throne only after a 20-minute argument with his father. Because he was never crowned he is disputed as a genuine king of France. Louis's nephew Henry was likewise considered by some to be Henry V, but the new regime did not recognise his claim and he never ruled.

Charles X named Louis Philippe as Lieutenant général du royaume, a regent to the young Henry V, and charged him to announce his desire to have his grandson succeed him to the Chamber of Deputies, the lower house of the French Parliament at the time, the French equivalent at the time of the UK House of Commons. Louis Philippe did not do this, in order to increase his own chances of succession. As a consequence, and because the French parliamentarians were aware of his liberal policies and of his popularity at the time with the French population, they proclaimed Louis Philippe as the new French king, displacing the senior branch of the House of Bourbon.

House of Bonaparte, Second French Empire (1852–1870)

The French Second Republic lasted from 1848 to 1852, when its president, Charles-Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, was declared Emperor of the French under the regnal name of Napoleon III. He would later be overthrown during the events of the Franco-Prussian War, becoming the last monarch to rule France.

Remove ads

Later pretenders

Summarize

Perspective

Various pretenders descended from the preceding monarchs have claimed to be the legitimate monarch of France, rejecting the claims of the president of France and of one another. These groups are:

- Legitimist claimants to the throne of France: Descendants of Louis XIV through the senior branch of the House of Bourbon, claiming precedence over the House of Bourbon-Orléans by virtue of primogeniture. In 1883, these were split into two factions as Henri V died without heirs, and his successor as head of the House of Bourbon would have a Spanish Bourbon. Earlier, King Philip V of Spain (also of the House of Bourbon) had earlier renounced the throne of France for himself and his descendants in the Peace of Utrecht. One faction were the Unionists, who recognized the Orléanist claimant Philippe as the pretender to the throne of France and disqualifying the Spanish branch from succession; the other were the Blancs d'Espagne, who insisted that claimant to the throne would remain to be from the Spanish branch according to primogeniture, disregarding the Spanish renunciation.

- Orléanist claimants to the throne of France: Descendants of Louis-Phillippe, himself descended from a junior line of the Bourbon dynasty, rejecting all heads of state since 1848. They argue that King Louis Philippe acquired legitimacy via popular sovereignty when the representatives of the French people in the French Parliament recognized him as king, with the Bourbons having already been rejected and dethroned by the French people after two revolutions.

- Bonapartist claimants to the throne of France: Descendants of Napoleon I and his brothers, rejecting all heads of state 1815–48 and since 1870. They argue that the Imperial throne needs to return to the House of Bonaparte, as the monarchs of this house had been chosen directly by the people through referendums, giving them legitimacy to reign via popular sovereignty, and both the Bourbons and the Orléans were rejected and dethroned through revolutions and that the Bonapartes were only dethroned due the interference of foreign enemies, with no popular revolution taking place to overthrow the Bonapartes and that the Third Republic was originally intended to be a provisional regime to return the throne to an Orléans or Bourbon (that never happened).

- English claimants to the throne of France: kings of England and later of Great Britain (renounced by Hanoverian King George III upon union with Ireland in 1800).

- Jacobite claimants to the throne of France: senior heirs-general of Edward III of England and thus his claim to the French throne, also claiming England, Scotland, and Ireland.

Remove ads

Timeline

See also

- Family tree of French monarchs

- Family tree of French monarchs (simplified)

- English claims to the French throne

- Fundamental laws of the Kingdom of France

- List of French royal consorts

- List of heirs to the French throne

- List of presidents of France

- Style of the French sovereign

- Succession to the French throne

- Coronation of the French monarch

Notes

- Louis the Pious and Charlemagne are both enumerated as "Louis I" and "Charles I" in the lists of French and German monarchs.

- Not to be confused with Louis II the German, son of Louis the Pious and king of East Francia (Germany). Both French and German monarchs saw themselves as the successors of Charlemagne, which is why many rulers share the same regnal name.

- Charles the Fat was initially king of East Francia (Germany) and Holy Roman Emperor. Given that he was the third emperor with that name, he is also known as Charles III. He must not to be confused with Charles the Simple, who is also enumerated as Charles III. This discrepancy originates from the regnal number adopted by Charles V, the first French king to assume one.[25]

- See main entry for references.

- "Capet" (Latin: Cappetus) was not actually a name, but a nickname adopted by later historians. It probably derived from chappe, an ecclesiastical mantle wore at the Abbey of Saint Martin of Tours.[44]

- Hugh was also descendant of Charlemagne's sons Louis the Pious and Pepin of Italy through his mother and paternal grandmother, respectively, and was also a nephew of Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor.[46]

- Because neither Hugh nor Philip were sole or senior king in their own lifetimes, they are not traditionally listed as kings of France and are not given ordinals.

- He lived from 15 to 19 November according to the continuator of Guillaume de Nangis.[61] The Chronique Parisienne Anonyme de 1316 à 1339 gives 13 and 18 November.[62] Modern sources often give his lifespan as 15–20 November.[63]

- Sources give his birth date as 6, 16, 20 or 26 April.

- Lower Navarre was integrated into France during his reign.

- Louis XVI's powers as king became obsolete following the March on Versailles on 5 October 1789, after which he became a hostage of the revolutionary forces.

- The Sénat proclaimed the deposition in absentia of Napoleon on 2 April, which was followed by the Corps législatif on 3 April. Napoleon wrote an act of abdication on 4 April renouncing the throne in favour of his son. However, this was not accepted by the Coalition, so he wrote an unconditional abdication on 6 April renouncing his rights and that of his family.[91]

- Although claimed as the shortest reigning monarch by the Guinness World Records,[97] this claim appears to be unsustained.[98] The exact circumstances of his "abdication" are unknown, as it was announced in a document signed by both Charles X and Louis, who is only called Dauphin. He is said to have been "king" between his father's signature and his own, as he (allegedly) initially refused to sign the document.

Coronations

- Charles II was crowned emperor on 25 December 875. For later Frankish and German emperors, see Holy Roman Emperor.

- Charles the Fat was most likely crowned on 20 May 885.[26] He was already king of East Francia since 28 August 876. He was also crowned emperor on 12 February 881.[27]

- Louis IV was crowned on 19 June 936, following a brief interregnum after the death of Rudolph.

- Lothair was crowned on 12 November 954.

- Louis V was crowned on 8 June 979.

- Hugh was elected and crowned king on 1 June 987, in Noyon. He was crowned again on 3 July in Paris by the archbishop of Reims. The latter date is usually regarded as the "official" start of the Capetian dynasty.[45]

- Henry I was crowned on 14 May 1027.

- Philip I was crowned on 23 May 1059.

- Louis VI was crowned on 3 August 1108.

- Louis VII was crowned as a child on 25 October 1131, and again on 25 December 1137 alongside Eleanor of Aquitaine.

- Philip II was crowned on 1 November 1179.

- Louis VIII was crowned on 6 August 1223.

- Louis IX was crowned on 29 November 1226.

- Philip III was crowned on 30 August 1271.

- Philip IV was crowned on 6 January 1286.

- Louis X was crowned on 24 August 1315.

- Charles IV was crowned on 21 February 1322.

- Philip VI was crowned on 29 May 1328.

- John II was crowned on 26 September 1350.

- Charles V was crowned on 19 May 1364.

- Charles VI was crowned on 4 November 1380.

- Henry (II) was crowned on 16 December 1431, at Notre-Dame de Paris.

- Charles VII was crowned on 17 July 1429.

- Louis XI was crowned on 15 August 1461.

- Charles VIII was crowned on 30 May 1484.

- Louis XII was crowned on 27 May 1498.

- Francis I was crowned on 25 January 1515.

- Henry II was crowned on 26 July 1547.

- Francis II was crowned on 18 September 1559.

- Charles IX was crowned on 15 May 1561.

- Henry III was crowned on 13 February 1575.

- Henry IV was crowned on 27 February 1594.

- Louis XIII was crowned on 17 October 1610.

- Louis XIV was crowned on 7 June 1654.

- Louis XV was crowned on 25 October 1722.

- Louis XVI was crowned on 11 June 1775.

- Louis XVIII decided not to have a coronation.

- Charles X was crowned on 29 May 1825, an unsuccessful attempt to revive the old monarchical traditions.

- Louis Philippe I decided not to have a coronation.

- A coronation ceremony for Napoleon III was planned, but never executed.

Remove ads

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads