Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Healthcare in Germany

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Germany has a universal multi-payer health care system. It is financed through a combination of statutory health insurance (Gesetzliche Krankenversicherung) and private health insurance (Private Krankenversicherung).[1]

Germany pioneered social health insurance in 1883. The first law covered certain groups of workers and raised national coverage to about 5–10 percent of the population.[2] Universal coverage was reached gradually and achieved by 1988.[3]

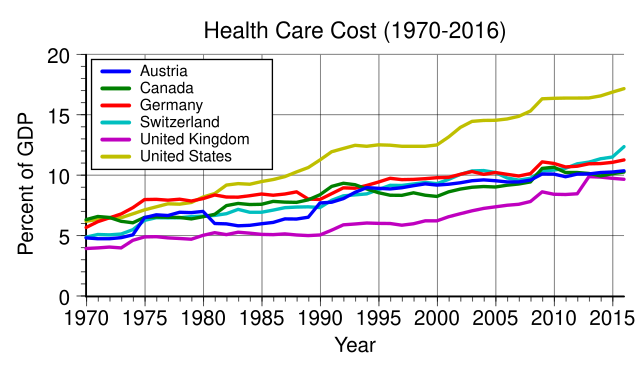

In 2010 the health sector’s turnover was about US$369 billion (€287 billion), equal to 11.6 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) and about US$4,500 (€3,510) per capita.[4] According to the World Health Organization, the system was 77% government-funded and 23% privately funded in 2004.[5] Total health spending in 2001 was 10.8 percent of GDP.[6]

Germany’s health outcomes are generally high. In 2004 male life expectancy was 78 years, ranking 30th worldwide. Physician density reached 4.5 per 1,000 inhabitants in 2021, up from 4.4 in 2019.[7] Infant mortality was 4.7 per 1,000 live births.[note 1][8]

The Euro Health Consumer Index ranked Germany seventh in 2015, describing it as one of the most consumer-oriented healthcare systems in Europe, with patients able to access almost any type of care without major restrictions.[9]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

1883

Germany has the world's oldest national social health insurance system,[10] with origins dating back to Otto von Bismarck's social legislation, which included the Health Insurance Bill of 1883, Accident Insurance Bill of 1884, and Old Age and Disability Insurance Bill of 1889. Bismarck stressed the importance of three key principles; solidarity, the government is responsible for ensuring access by those who need it, subsidiarity, policies are implemented with the smallest political and administrative influence, and corporatism, the government representative bodies in health care professions set out procedures they deem feasible.[11] Mandatory health insurance originally applied only to low-income workers and certain government employees, but has gradually expanded to cover the great majority of the population.[12]

1883–1970

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2020) |

Unemployment insurance was introduced in 1927.[13] In 1932, the Berlin treaty (1926) expired and Germany's modern healthcare system started shortly afterwards. In 1956, Laws on Statutory health insurance (SHI) for pensioners come into effect. New laws came in effect in 1972 to help finance and manage hospitals. In 1974 SHI covered students, artists, farmers and disabled living shelters. Between 1977 and 1983 several cost laws were enacted. Long-term care insurance (Pflegeversicherung) was introduced in 1995.

1976–2000

Since 1976, the government has convened an annual commission, composed of representatives of business, labor, physicians, hospitals, and insurance and pharmaceutical industries. The commission takes into account government policies and makes recommendations to regional associations with respect to overall expenditure targets.[14] Historically, the level of provider reimbursement for specific services is determined through negotiations between regional physicians' associations and sickness funds.[citation needed]

In 1986, expenditure caps were implemented and were tied to the age of the local population as well as the overall wage increases. Copayments were introduced in the 1980s in an attempt to prevent overutilization and control costs. [citation needed]

21st century

As of 2007, providers have been reimbursed on a fee-for-service basis; the amount to be reimbursed for each service is determined retrospectively to ensure that spending targets are not exceeded. Capitated care, such as that provided by U.S. health maintenance organizations, has been considered as a cost-containment mechanism, but since it would require consent of regional medical associations, it has not materialized.[15]

The average length of hospital stay in Germany has decreased in recent years from 14 days to 9 days, still considerably longer than average stays in the U.S. (5 to 6 days).[16][17] The difference is partly driven by the fact that hospital reimbursement is chiefly a function of the number of hospital days, as opposed to procedures or the patient's diagnosis. Drug costs have increased substantially, rising nearly 60% from 1991 through 2005. Despite attempts to contain costs, overall health care expenditures rose to 10.7% of GDP in 2005, comparable to other western European nations, but substantially less than that spent in the U.S. (nearly 16% of GDP).[18]

The system is decentralized[when?] with private practice physicians providing ambulatory care, and independent, mostly non-profit hospitals providing the majority of inpatient care. Approximately 92%[when?] of the population are covered by a 'Statutory Health Insurance' plan, which provides a standardized level of coverage through any one of approximately 1,100 public or private sickness funds. Standard insurance is[when?] funded by a combination of employee contributions, employer contributions and government subsidies on a scale determined by income level. Higher-income workers sometimes[when?] choose to pay a tax and opt-out of the standard plan, in favor of 'private' insurance. The latter's premiums are not linked to income level, but instead to health status.[19][20]

Remove ads

Regulation

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2017) |

Since 2004 the Federal Joint Committee (Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss) has overseen regulation of the German health care system. It is a public body that issues binding rules under health reform laws and makes routine coverage decisions.[21]

The committee has 13 voting members: representatives of insurers, hospitals, physicians, dentists, and three independent members. Five patient representatives take part in an advisory role but do not vote.[22]

It is governed by the Fifth Book of the German Social Code (Fünftes Sozialgesetzbuch). One of its main tasks is to decide which treatments and services statutory health insurance must cover. Decisions are based on whether care is necessary, cost-effective, sufficient, and appropriate.[23]

Remove ads

Health insurance

Summarize

Perspective

Since 2009, health insurance has been compulsory for the entire population in Germany, extending coverage from most residents to all citizens and permanent residents.[24]

Germany’s system consists of two main branches: public health insurance (gesetzliche Krankenversicherung, GKV) and private health insurance (private Krankenversicherung, PKV). Coverage is regulated by the Sozialgesetzbuch V (SGB V), with benefits defined by the Federal Joint Committee.

As of 2024, about 88% of the working population is insured through statutory funds and around 11% through private insurance.[25][26] A very small minority remain uninsured despite the legal requirement.[27] The annual income threshold for opting into private insurance is €73,800 (2025).

Statutory health insurance (GKV)

As of 2025, salaried employees earning less than €73,800 per year are automatically enrolled in one of about 105 non-profit sickness funds (Krankenkassen).[28] This income threshold is known as the Versicherungspflichtgrenze. Employees above this limit may choose private insurance.

Freelancers and self-employed persons may join either system regardless of income, though public insurers are not obliged to accept them. Foreign freelancers have reported difficulties obtaining coverage from both GKV and PKV.[29] As health insurance is a requirement for residence permits, rejection can place residency at risk.

In GKV, contributions:

- are set by the Federal Ministry of Health under SGB V, restricted to “economically viable, sufficient, necessary and meaningful services”;

- are income-based, at 14.6% of salaried income up to €64,350 per year (2021), shared equally between employer and employee;

- include an additional contribution rate determined by each fund, averaging 1.3% in 2021;

- cover dependent family members at no extra cost (Familienversicherung);

- operate on a pay-as-you-go basis, with the working population financing the retired population.[30]

GKV insurers reported reserves of more than €18 billion in 2017,[31] but a deficit of €6.25 billion by early 2025.[32]

Funds must accept all applicants and offer a comprehensive benefits package. Members may choose optional tariffs such as higher deductibles, reimbursement bonuses, or reduced benefits for lower contributions.[33][34][35]

Self-employed persons and unemployed individuals without benefits must pay the full premium. Those unemployed but insured under GKV pay a minimum of €279.60 per month (2025).[36]

Provider payment is negotiated corporatistically between physicians’ associations and insurers at the Länder level.[37] Social welfare beneficiaries are also covered, with municipalities paying contributions.[38]

Private health insurance (PKV)

Residents may qualify for private insurance if their annual income exceeds €73,800 (2025), or if they are civil servants, self-employed, or students.[39] About 11% of the population is privately insured.[40][41]

In PKV, the premium:

- is defined by contract between insurer and insured;

- depends on chosen services, age, and health status at entry;

- includes mandatory reserves for old age (Alterungsrückstellungen).[42][43]

Returning from PKV to GKV is only possible under certain conditions (e.g. under age 55 and below the income threshold). For older policyholders, PKV can become more expensive than GKV.[44]

Civil servants receive state reimbursement for about half of medical costs and usually choose PKV for the remainder.[45] Private insurers also offer supplementary policies, for example for dental treatment, vision, or care abroad.

Germany also has a “second health market” for privately financed services not covered by GKV or PKV, such as fitness, wellness, assisted living, and health tourism. In 2011, publicly insured patients spent €1.5 billion on such services, and about 82% of physicians offered additional treatments.[46]

Coverage decisions in GKV are made by the Federal Joint Committee, which defines sufficient, necessary, and cost-effective services. Because statutory dental benefits are limited, supplementary dental insurance is common.[47]

Supplementary insurance

Many residents purchase additional insurance alongside GKV or PKV. Common forms include dental coverage, supplementary hospital insurance, and daily sickness benefits.

Private health insurance in Germany often covers 90–100% of dental costs, so supplementary dental insurance is usually unnecessary. Public health insurance (GKV), however, offers much lower subsidies (e.g., low subsidy for professional cleaning) making supplementary coverage important for many GKV members. [48] [49] [50]

Reimbursement under public health insurance's dental coverage is capped in the first years of coverage, and dentists calculate fees according to standardized schedules (GOZ for dental, GÖA for medical). [51] Supplementary insurance reimburses up to these maximum rates; patients pay costs above them.[52]

Self-payment for foreign or uninsured patients

Hospitals in Germany generally require advance payment from patients without German insurance. Clinics provide cost estimates that must be settled in full or in part before treatment. At university hospitals, deposits may range from the entire estimated amount to a smaller percentage, with patients responsible for unexpected costs such as complications.[53][54]

Coverage by status

Children

Children must be health insurance, whether through the public or private system, under the system of their parents. [55]

- If both parents are in GKV, children are included at no additional cost through Familienversicherung.[56]

- If both parents are in PKV, the child must also be insured privately.

- If parents are split (one GKV, one PKV), the child may be in either system. However, GKV family insurance is excluded if: the parents are married or in a registered partnership; the privately insured parent earns more than the publicly insured parent; and that monthly income exceeds the threshold (€73,800 in 2025). [55] [57] [58]

Unemployed persons

Health insurance remains compulsory during unemployment.

- Unemployment Benefit I (Arbeitslosengeld I): recipients are automatically insured under GKV, with contributions paid by the Federal Employment Agency. Privately insured persons may stay in PKV if they apply for exemption.[59]

- Unemployment Benefit II (Bürgergeld): recipients remain in GKV, with contributions covered by the Jobcenter. PKV policyholders receive a subsidy but must pay costs above the public base rate.

- Without benefits: individuals not receiving unemployment benefits must self-insure, either through voluntary GKV (minimum ~€280 per month in 2025) or by continuing PKV at full cost. [60]

Uninsured

Although insurance is mandatory, some people remain uninsured. In 2019, about 61,000 people (less than 0.1% of the population) had no coverage, with higher rates among the self-employed (0.4%) and unemployed (0.8%).[61] Professional associations estimate the true figure may be several hundred thousand. In Hamburg alone, more than 20,000 residents are thought to be uninsured.[62]

Employee social insurance

Employees contribute jointly with employers to three mandatory insurances:

- health insurance,

- accident insurance (Arbeitsunfallversicherung), funded entirely by employers and covering work and commuting accidents,

- long-term care insurance (Pflegeversicherung), financed equally by employer and employee at about 2% of income.

Insuring organizations

After reunification in 1991, a segmented system was introduced in the new federal states, followed by mergers and consolidations.[63]

The number of statutory health insurance funds has declined by more than 90% since 1970, from 1,815 funds in 1970 to 960 in 1995 and 96 in 2023.[63][64]

The Gesundheitsfonds (Health Fund), introduced in 2009, and the GKV-Wettbewerbsstärkungsgesetz (2007) accelerated this consolidation.[63]

Current statutory fund types include:

- Ersatzkasse,

- Allgemeine Ortskrankenkasse (AOK),

- Betriebskrankenkasse (BKK),

- Innungskrankenkasse (IKK),

- Knappschaft (Krankenkasse),

- Landwirtschaftliche Krankenkasse.

As long as an insured person is eligible to choose, they may join any statutory fund that accepts new members.[65]

Remove ads

Economics

Summarize

Perspective

The Institut Arbeit und Technik (IAT) at the University of Applied Sciences Gelsenkirchen describes the health sector using an "onion model of health care economics":[67]

- The core consists of ambulatory and inpatient acute care, geriatric care, and health administration.

- Surrounding this are wholesale and supplier industries, including the pharmaceutical industry, medical technology, health services, and the trade of medical products.

- On the outer margins are fitness and spa facilities, assisted living, and health tourism.

In 2009, some analysts argued that a fully regulated market, as in the UK, would not suit Germany, while a largely deregulated model, as in the United States, would also be suboptimal. Instead, a hybrid system combining social balance with competitive elements was considered most effective.[68] In practice, Germany’s healthcare market is shaped by frequent reforms to the Social Security Code (Sozialgesetzbuch, SGB) over the past three decades.[timeframe?]

Health care, including industry and services, is one of the largest sectors of the German economy. Direct inpatient and outpatient care represents about one quarter of the sector.[4] In 2007, about 4.4 million people were employed in healthcare, roughly one in ten workers.[69] Total expenditure in 2010 amounted to €287.3 billion, or 11.6% of gross domestic product (GDP), equivalent to about €3,510 per capita.[70]

Drug costs

The pharmaceutical industry plays a major role in Germany both within and beyond direct health care. Expenditure on pharmaceutical drugs accounts for almost half the costs of the hospital sector. Between 2004 and 2010, drug spending increased by an average of 4.1% per year, prompting several health care reforms.

In 2010–2011, for the first time since 2004, pharmaceutical expenditure fell, from €30.2 billion in 2010 to €29.1 billion in 2011 (a decline of €1.1 billion or 3.6%). This resulted from amendments to the Social Security Code, including raising the manufacturer discount from 6% to 16%, a price moratorium, expanded rebate contracts, and higher discounts from wholesalers and pharmacies.[71]

Germany uses reference pricing and cost sharing to encourage generic substitution. Newer and more effective drugs often require higher patient co-payments.[72] Since 2013, however, out-of-pocket payments for medications have been capped at 2% of household income, and 1% for people with chronic illnesses.[73]

Health insurance costs

Germany’s aging population places increasing strain on the health insurance system. The public system (GKV) relies on contributions from the working population to finance the care of retirees, without building reserves.[citation needed] By contrast, private insurers (PKV) set aside part of premiums in aging provisions to stabilize costs in old age.[citation needed]

By 2050, one-third of the population will be aged 60 or older.[74] With fewer working-age contributors, GKV could face substantial cost increases. Some experts[which?] predict that contributions might rise to between 25% and 32% of gross salary in coming decades.[citation needed]

Remove ads

Statistics

Summarize

Perspective

In a sample of 13 developed countries Germany was seventh in its population weighted use of medications in 2009 and tenth in 2013. The drugs studied were selected on the basis that the conditions treated had high incidence, prevalence and/or mortality, caused significant long-term morbidity and incurred high levels of expenditure and significant developments in prevention or treatment had been made in the last 10 years. The study noted considerable difficulties in cross border comparison of medication use.[75] As of 2015 it had the highest number of dentists in Europe with 64,287.[76]

Hospitals

Types:

There are[when?] three main types of hospital in the German healthcare system:

- Public hospitals (öffentliche Krankenhäuser).

- Charitable hospitals (frei gemeinnützige Krankenhäuser).

- Private hospitals (Privatkrankenhäuser).

As of 2011, the average length of hospital stay in Germany had decreased from 14 days to 9 days,[77] still considerably longer than average stays in the United States (5 to 6 days)[78] from 1991 through 2005, drug costs have increased substantially, rising nearly 60% . Despite attempts to contain costs, overall health care expenditures rose to 10.7% of GDP in 2005, comparable to other western European nations, but substantially less than that spent in the U.S. (nearly 16% of GDP).[79]

In 2017 the BBC reported that compared with the United Kingdom the Caesarean rate, the use of MRI for diagnosis and the length of hospital stay are all higher in Germany.[80]

Remove ads

Waiting times and capacity

Summarize

Perspective

In 1992, a study by Fleming et al. 19.4% of German respondents said they had waited more than 12 weeks for their surgery. (cited in Siciliani & Hurst, 2003, p. 8),[81]

In the Commonwealth Fund 2010 Health Policy Survey in 11 countries, Germany reported some of the lowest waiting times. Germans had the highest percentage of patients reporting their last specialist appointment took less than 4 weeks (83%, vs. 80% for the U.S.), and the second-lowest reporting it took 2 months or more (7%, vs. 5% for Switzerland and 9% for the U.S.). 70% of Germans reported that they waited less than 1 month for elective surgery, the highest percentage, and the lowest percentage (0%) reporting it took 4 months or more.[82] Waits can also vary somewhat by region. Waits were longer in eastern Germany according to the KBV (KBV, 2010), as cited in "Health at a Glance 2011: OECD Indicators".[83]

As of 2015, waiting times in Germany were reported to be low for appointments and surgery, although a minority of elective surgery patients face longer waits.[84][85]

According to the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians in 2016,(KBV, Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung), the body representing contract physicians and contract psychotherapists at federal level, 56% of Social Health Insurance patients waited 1 week or less, while only 13% waited longer than 3 weeks for a doctor's appointment. 67% of privately insured patients waited 1 week or less, while 7% waited longer than 3 weeks. The KBV reported that both Social Health Insurance and privately insured patient experienced low waits, but privately insured patients' waits were even lower. [86]

As of 2022, Germany had a large hospital sector capacity measured in beds with the highest rate of intensive care beds among high income countries and the highest rate of overall hospital capacity in Europe.[87] High capacity on top of significant day surgery outside of hospitals (especially for ophthalmology and orthopaedic surgery) with doctors paid fee-for-service for activity performed are likely factors preventing long waits, despite hospital budget limitations.[81] Activity-based payment for hospitals also is linked to low waiting times.[81] As of 2014, Germany had introduced Diagnosis-related group activity-based payment for hospitals with a soft cap budget limit.[88]

Remove ads

See also

Notes

- Infant mortality definitions differ by country. For example, the United States includes infants under 500 g, while Germany does not. Social factors also influence outcomes.

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads