Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

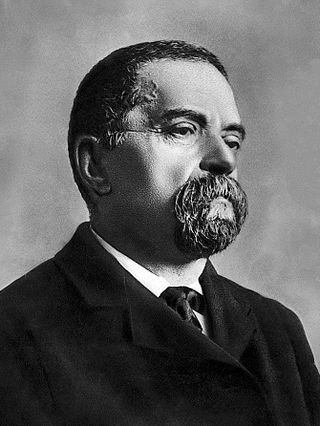

Giovanni Schiaparelli

Italian astronomer and science historian (1835–1910) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Giovanni Virginio Schiaparelli ForMemRS HFRSE (/ˌskæpəˈrɛli, ˌʃæp-/ SKAP-ə-REL-ee, SHAP-,[2][3] US also /skiˌɑːp-/ skee-AHP-,[3][4] Italian: [dʒoˈvanni virˈdʒiːnjo skjapaˈrɛlli]; 14 March 1835 – 4 July 1910) was an Italian astronomer and science historian. Schiaparelli established the Martian system of nomenclature still in use today; before him, features of the planet bore the names of contemporary astronomers, similar to the lunar map of van Langren that preceded that of Hevelius.[5]

Remove ads

Biography

Summarize

Perspective

Born in Savigliano, Piedmont, on 14 March 1835, Schiaparelli graduated from the University of Turin in 1854. From 1857 to 1859, he spent a period of post-graduate study in Berlin under the guidance of the director of the Berlin Observatory Johann Franz Encke.[6] In 1859–1860 he worked in Pulkovo Observatory near Saint Petersburg. Back in Italy, he received the appointment of second astronomer to the Brera Observatory in Milan, where he worked for over forty years. In 1862, he succeeded Francesco Carlini as director of the Observatory.

Schiaparelli became internationally famous for his studies of Mars. He was responsible for some of the best contemporary maps of Mars and was the first to locate many of the features of the planet with considerable accuracy. In his classic work on Martian observations, La Planète Mars, published in 1892, Camille Flammarion stated that Schiaparelli's was 'the greatest work which has been carried out with regard to Mars.'[7]

Schiaparelli was a member of many academies, Italian and foreign, including the Accademia dei Lincei, the Royal Academy of Sciences of Turin and the Regio Istituto Lombardo. He was appointed a senator of the Kingdom of Italy in 1889. Schiaparelli was the recipient of many national and international honours, including the unprecedented award of two Lalande Prizes from the French Academy of Sciences. In 1872, he was awarded the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society "for his researches on the connexion between the orbits of comets and meteors". Schiaparelli was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1901.[8] He retired in 1900 and died in Milan on 4 July 1910.

Remove ads

Mars

Summarize

Perspective

Among Schiaparelli's contributions are his telescopic observations of Mars. In his initial observations, he named the "seas" and "continents" of Mars. During the planet's "great opposition" of 1877, he observed a dense network of linear structures on the surface of Mars, which he called canali in Italian, meaning "channels", but the term was mistranslated into English as "canals".[9]

While the term "canals" indicates an artificial construction, the term "channels" connotes indicates that the observed features were natural configurations of the planetary surface. From the incorrect translation into the term "canals", various assumptions were made about life on Mars; as these assumptions were popularized, the "canals" of Mars became famous, giving rise to waves of hypotheses, speculation, and folklore about the possibility of Martians, intelligent life living on Mars. Among the most fervent supporters of the artificial-canal hypothesis was the American astronomer Percival Lowell, who spent much of his life trying to prove the existence of intelligent life on the red planet.[9] After Lowell's death in 1916, astronomers developed a consensus against the canal hypothesis, but the popular concept of Martian canals excavated by intelligent Martians remained in the public mind for the first half of the 20th century and inspired a corpus of works of classic science fiction.

Later, with notable thanks to the observations of the Italian astronomer Vincenzo Cerulli, scientists came to the conclusion that the famous channels were actually mere optical illusions. The last popular speculations about canals were finally put to rest during the spaceflight era beginning in the 1960s, when visiting spacecraft such as Mariner 4 photographed the surface with much higher resolution than Earth-based telescopes, confirming that there are no structures resembling "canals".

In his book Life on Mars, Schiaparelli wrote: "Rather than true channels in a form familiar to us, we must imagine depressions in the soil that are not very deep, extended in a straight direction for thousands of miles, over a width of 100, 200 kilometres and maybe more. I have already pointed out that, in the absence of rain on Mars, these channels are probably the main mechanism by which the water (and with it organic life) can spread on the dry surface of the planet."

Remove ads

Martian nomenclature

Summarize

Perspective

In his 1877 Map of Mars, Schiaparelli devised an entirely new system of nomenclature that quickly superseded the previous one established by Richard A. Proctor. An expert on ancient astronomy and geography, Schiaparelli used Latin names, drawn from the myths, history and geography of classical antiquity; dark features were named after ancient seas and rivers, light areas after islands and legendary lands.

When E. M. Antoniadi took over as the leading telescopic observer of Mars in the early 20th century, he followed Schiaparelli's names rather than Proctor's, and the Proctorian names quickly became obsolete. In his encyclopedic work La Planète Mars (1930), Antoniadi used all Schiaparelli's names and added more of his own from the same classical sources. However, there was still no 'official' system of names for Martian features.

In 1958, the International Astronomical Union set up an ad hoc committee under Audouin Dollfus, which settled on a list of 128 officially recognised albedo features. Of these, 105 came from Schiaparelli, 2 from Camille Flammarion, 2 from Percival Lowell, and 16 from Antoniadi, with an additional 3 from the committee itself.

Astronomy and history of science

| 69 Hesperia | 29 April 1861 | MPC |

An observer of objects in the Solar System, Schiaparelli worked on binary stars, discovered the large main-belt asteroid 69 Hesperia on 29 April 1861,[11] and demonstrated that the meteor showers were associated with comets.[12] He proved, for example, that the orbit of the Leonid meteor shower coincided with that of the comet Tempel-Tuttle. These observations led the astronomer to formulate the hypothesis, subsequently proved to be correct, that the meteor showers could be the trails of comets. He was also a keen observer of the inner planets Mercury and Venus. He made several drawings and determined their rotation periods.[12] In 1965, it was shown that his and most other subsequent measurements of Mercury's period were incorrect.[13]

Schiaparelli was a scholar of the history of classical astronomy. He was the first to realize that the concentric spheres of Eudoxus of Cnidus and Callippus, unlike those used by many astronomers of later times, were not to be taken as material objects, but only as part of an algorithm similar to the modern Fourier series.[citation needed]

Remove ads

Honors and awards

Awards

- Lalande Prize (1868)

- Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society (1872)

- Bruce Medal (1902)

Named after him

- The main-belt asteroid 4062 Schiaparelli,[12] named on 15 September 1989 (M.P.C. 15090).[14]

- The lunar crater Schiaparelli[12]

- The Martian crater Schiaparelli[12]

- Schiaparelli Dorsum on Mercury[15]

- The 2016 ExoMars' Schiaparelli lander.[16]

Remove ads

Relatives

His niece, Elsa Schiaparelli, became a noted designer or maker of haute couture.[17]

Selected writings

- Sulla determinazione della posizione geografica dei luoghi per mezzo di osservazioni astronomiche (in Italian). Milano. 1872.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1873 – Le stelle cadenti (The Falling Stars)

- Osservazioni sulle stelle doppie (in Italian). Milano: Hoepli. 1888.

- Sulla distribuzione apparente delle stelle visibili ad occhio nudo (in Italian). Milano: Hoepli. 1889. Bibcode:1889sdas.book.....S.

- 1893 – La vita sul pianeta Marte (Life on Mars)

- 1925 – Scritti sulla storia della astronomia antica (Writings on the History of Classical Astronomy) in three volumes. Bologna. Reprint: Milano, Mimesis, 1997.

Remove ads

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads