Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Politics of Papua New Guinea

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The politics of Papua New Guinea takes place in a framework of a parliamentary representative democratic multi-party system, whereby the prime minister is the head of government. Papua New Guinea is an independent Commonwealth realm, with the monarch serving as head of state and a governor-general, nominated by the National Parliament, serving as their representative. Executive power is exercised by the government. Legislative power is vested in both the government and parliament.

Constitutional safeguards include freedom of speech, press, worship, movement, and association. The judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature.

Remove ads

Executive branch

Summarize

Perspective

Main office-holders

Papua New Guinea is a Commonwealth realm with Charles III as king. The monarch's representative is the governor-general of Papua New Guinea, who is elected by the unicameral National Parliament of Papua New Guinea.[1]: 9 Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands are the only realms in which the governor-general is elected by parliament; the governor-general is still formally appointed by the monarch per parliamentary vote. The governor general acts on the advice of the prime minister and the cabinet.

The Constitution of Papua New Guinea provides for the executive to be responsible to parliament as the representative of the Papua New Guinean people.[citation needed] The National Parliament elects the prime minister of Papua New Guinea, who is then appointed by the governor-general. The other ministers are appointed by the governor-general on the prime minister's advice and form the National Executive Council of Papua New Guinea, which acts as the country's cabinet. The National Parliament has 111 seats, of which 22 are occupied by the governors of the 21 provinces and the National Capital District, and sits for a maximum of five years.[1]: 9 [2] Candidates for members of parliament are voted upon when the prime minister asks the governor-general to call a national election.

The governments of Papua New Guinea are characterized by weak political parties and highly unstable parliamentary coalitions. The prime minister, elected by Parliament, chooses the other members of the cabinet. Each ministry is headed by a cabinet member, who is assisted by a permanent secretary, a career public servant, who directs the staff of the ministry. The cabinet consists of members, including the prime minister and ministers of executive departments. They answer politically to the parliament.

The governor general appoints the chief justice of the supreme court on the advice of the prime minister and the leader of the opposition. The governor general appoints the other justices with the advice of a judicial commission. The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (based in the United Kingdom) serves as the highest appellate court.

Remove ads

Legislative branch

Summarize

Perspective

Papua New Guinea has a unicameral National Parliament, previously known as the House of Assembly. It has 111 seats, with 89 elected from single-member "Open" electorates and 22 from province-level "Provincial" electorates. Members are elected by popular vote to serve five-year terms. The most recent election was held in June to July of 2022.

Members of Parliament are elected from the nineteen provinces and the National Capital District. After independence in 1975, members were elected by the first past the post system, with winners frequently gaining less than 15% of the vote. Electoral reforms in 2001 introduced the Limited Preferential Vote system (LPV), a modified version of alternative vote, where voters number their first three choices among the candidates. The first general election to use LPV was held in 2007.

Parliament introduced reforms in June 1995 to change the provincial government system, with provincial members of Parliament becoming provincial governors, while retaining their national seats in Parliament. However, if a provincial member accepts a position as a cabinet minister, the role of governor falls to one of the Open members of Parliament from the province.

As of 1 February 2019, Papua New Guinea was one of only three countries in the world out of 235 that had no women in its legislative branch or parliament.[3] There have only been seven women elected to parliament ever, one of the lowest rates of legislative representation in the world.[citation needed] Proposals to have nominated (unelected) women MPs have not gained support.[4]

The Speaker of the National Parliament of Papua New Guinea has considerable power, and can allow the executive to exercise considerable control over parliament. This has been described as a "fatal flaw" of the constitution.[5]: 7

While dual citizens cannot hold office, naturalised citizens can if they renounce their other citizenship(s). As of 2023, many naturalised citizens had served as MPs, with 17 becoming ministers in government.[6]

Remove ads

Political parties and elections

Summarize

Perspective

Papua New Guinea has maintained continuous democratic elections and changes in government since independence.[7]: 1 [8]: 10 While seat results are often contested, the overall results of elections are accepted.[7]: 7 Elections in PNG attract numerous candidates. After independence in 1975, members were elected by the first-past-the-post system, with many winners gaining less than 10% of the vote.[8]: 17 In 1972, there was an average of six candidates contesting each seat; by 2002 that reached 26, with a higher proportion of independents.[9]: 100 Voting now takes place through the Limited Preferential Vote system (LPV), a version of the alternative vote.[7]: 2 [8]: 17 Under this system, voters must give preference votes for at least three candidates.[10]: 118 This is intended to reduce confrontation due to the need to court second and third preferences, as well as provide outlets for those, especially women, who might be pressured to select one candidate by others to also vote for their preferred candidate.[10]: 119

While political parties exist, they are not ideologically differentiated. Instead they generally reflect the alliances made between their members, and have little relevance outside of elections. All governments since 1972 have been coalitions, and the number of independent candidates that run has increased. Having no party makes it easier for winning politicians to negotiate with those trying to establish a majority coalition. When formed, such coalitions are unstable due to the potential for party hopping,[11]: 3 [7]: 7 referred to as "yo-yo" politics. Almost all parties have formed coalition with the others,[8]: 13 and some coalitions have consisted of up to 10 separate parties. Ministerial positions are valuable,[1]: 9 and constituents may often have little issue with their elected representatives switching parties to join the government, as it gives their district more representation.[12]: 94 Political parties can have MPs in government while others remain in opposition.[13]: 255, 269 Opposition MPs have been appointed to government.[13]: 262

Changes in government mostly affected patronage and individual positions, rather than changing government priorities and programmes.[1]: 6 Due to this, despite the fractiousness of politics, policy is relatively stable.[14]: 62 Many parties might run on similar platforms, with common policies including rural development, better health, education, and other public services, and being anti-corruption. This further weakens policy debate, as candidates campaign on local representation rather than their platforms.[12]: 95 Party whipping is uncommon.[14]: 61 The lack of strong parties lasting between elections contributes to poor finances, meaning parties can not really support candidates outside of personal funds from party leaders.[14]: 60 Pre-election coalitions are rare.[14]: 62 A weak parliament has also resulted in a much stronger executive, a process strengthened by governments using procedural methods to control parliament.[15]: 247 An increasing reliance on judicial methods to combat the government has increased the risk of the judiciary being seen as politicised.[15]: 247–248

The support bases of political parties are usually personal or geographical. Even when nominally national parties emerge, they are often strong in specific regions.[16]: 45 [8]: 15 Most parties exist only for a short time, and are highly dependent on their leaders.[14]: 64 Conversely, initial governing coalitions are large, albeit fragile, as MPs seek to gain the benefits of being in government.[5]: 1 Coalitions that emerge during mid-term political disputes however may be much closer to a basic majority.[5]: 6

For the first couple of decades of independence, there was at least one change of government within each parliamentary period.[11]: 4 In total, only two prime ministers have finished a full term from election to election.[17][7]: 7 Votes of no confidence are common, and while few are successful,[1]: 12 [18] multiple prime ministers have pre-emptively resigned to try and engineer reselection or adjourned parliament in order to avoid them.[11]: 5 [1]: 20 [9]: 101 Prime ministers also engage in large-scale reshuffles to split opposition parties and craft new majorities.[19] In October 2016, the government of Peter O'Neill launched a motion of no confidence against itself while much of the opposition was absent, which was voted down 78 to 2.[5]: 8 The first successful vote of no confidence occurred in 1980, with one following in 1985, and the third in 1988, with many unsuccessful attempts in between.[9]: 101 Motions of no confidence must be "constructive", ie. they must include a nomination for a replacement prime minister.[20] (This does not apply in the final 12 months of a parliament, when a successful motion of no confidence would lead directly to an election.[5]: 11 ) Debate over a motion of no confidence is limited to seven days. They have historically been unpredictable, with embattled prime ministers sometimes surviving, and those with large coalitions sometimes falling.[5]: 3

The political culture is influenced by existing kinship and village ties, with communalism an important cultural factor given the many small and fragmented communities.[16]: 38–40 Regional and local identities are strong, and traditional politics has integrated with the modern political system.[16]: 46 There is a broad Papuan regional identity, and to some extent a highlands one, which can affect politics.[12]: 93 However, outside of Bougainville, regional politics are autonomist rather than separatist, with separatism often used as rhetoric rather than as an ultimate goal.[21]: 71 The importance of community ties to their land are reflected in the legal system, with 97% of the country designated as customary land, held by communities. Many such effective titles remain unregistered and effectively informal.[22]: 53–54

Voting often occurs along tribal lines,[23] an issue exacerbated by politicians who might be able to win off the small vote share provided by a unified tribe. Political intimidation and violence are common. Politicians have been prevented from campaigning in tribes with a rival candidate, and candidates are sometimes put up by opponents to split a different tribe's vote.[11]: 5 [8]: 14, 18 One saying to describe candidate choice is "Candidates do not win because they are endorsed by parties; rather parties endorse candidates who are going to win".[24] Bloc voting is practiced by some communities, especially in the highlands.[12]: 96 Large numbers of independent candidates means that winners are often elected on very small pluralities, including winning less than 10% of votes. Such results raise concerns about the mandates provided by elections.[11]: 4–5

In every election prior to at least 2004, the majority of incumbents lost their seats. This has created an incentive for newly elected politicians to seek as much personal advantage as possible within their term.[11]: 4 Each MP controls Rural Development Funds for their constituency, providing easy opportunities for corruption.[11]: 10 It also means many prioritise new expenditure, rather than delivering existing services.[25] This has led to the impression that politics is a type of business. Parties in parliament serve primarily as factions. They have no particular hold on MPs,[9]: 100 except as a vehicle for personal advancement.[9]: 103 Political strategy and tactics to achieve power as an end in itself matter more than questions of policy.[9]: 100 This short-term procedural method of politics impedes long-term political strategy.[9]: 101 The total amount of funding under the discretionary control of each MP is amongst the highest in the world.[17] This has generated significant cynicism, and reduced the perceived legitimacy of the national government.[26]: 318 The control of such funds may also contribute to commonality and severity of electoral violence.[17] Other challenges to elections include issues with administration, issues with electoral rolls, and vote buying.[7]: 7 [27]: 5 The provision of constituency funds to MPs has been delayed by prime ministers to influence coalition-building.[1]: 9

Corruption is a widespread issue within Papua New Guinea. While notable instances have been identified amongst high-profile individuals, spreading petty corruption has likely had a greater effect of degrading government services. While some corruption is for personal gain, other corruption emerges from the social obligations of the wantok system, with constituents expecting reciprocal benefits and loyalty from their elected officials and from others in their communities and kin networks.[28]: 155–156 This exacerbates national political stability, keeping political contests local and focused on allegiances.[9]: 100 Politicians jailed for corruption have been re-elected, as their corrupt activities were seen an expected part of benefiting their communities. This clash of individual community expectations and local acceptance of what might be called corruption with widespread disillusionment over national corruption is likely one reason that anti-corruption actions rarely match political rhetoric.[28]: 157–158 These cultural expectations also sometimes clash with the formal legal and political system which inherited Australian norms.[22]: 41–42 Resentment of elites and clear inequality also drive expectations of patronage.[29]: 209 Former Prime Minister Mekere Morauta described corruption as "systematic and systemic".[22]: 39

The control of constituency funds has also resulted in MPs being seen as individually responsible for the delivery of government services, especially as few other pathways for government services exist, compounding the cultural importance of expectations of rewards for voting for a winning candidate. This responsibility for services is thought to contribute to high levels of absenteeism in parliament, and thus means MPs are not able to effectively act as lawmakers within the Westminster system of government. Instability in parliament further hampers lawmaking. A 2018 commission found 370 laws thought to be at least 50 years out of date.[30] Constituency boundaries are the same as administrative boundaries, strengthening the conceptual link between elections and service provisions. This also distorts politics, by making electoral boundaries unresponsive to changes in population.[27]: 3 Changing these boundaries to reflect population is hindered by the vested interests of those elected under the current system.[4] Rural communities have a much more difficult time accessing government services, with facilities such as banking sometimes being days of travel away.[29]: 208 In some rural areas, villages have little interaction with the state.[8]: 21

The Constitutional Planning Committee that decided to adopt a Westminster system expected that the legislature would act as a check on the executive, however political developments did not achieve this. Instead, the executive exerts significant control over parliament, especially with its ability to adjourn the parliament and thus prevent legislative scrutiny.[9]: 99–100 Adjournments also avoid votes of no confidence, and can last for months.[9]: 101

Governments cannot face no confidence votes within six months of the most recent election.[1]: 6 This was extended to 18 months in 1991, and 30 months in 2012,[1]: 10 although in 2015 the supreme court ruled such changes were unconstitutional.[1]: 11 Votes of no confidence are generally not held in the fifth year of a parliament, as this would trigger an immediate election,[1]: 18 risking the seats of incumbent MPs.[20]

Ministerial tenures are often short, averaging half the length of a parliament from 1972 to 2016. This 29–30 months is reduced to just 24 months if considering service under one prime minister.[1]: 17 The average length a minister spends at a particular portfolio is even shorter, at just 16 months, or 15 months under one prime minister. Excluding the unusual 1972–77 parliament, the average is just 12 months.[1]: 18

The Organic Law on the Integrity of Political Parties and Candidates, which passed in December 2000, incentivised the formation of political parties and barred independent MPs from electing the prime minister.[11]: 6–7 Changes in 2003 barred party hopping and forced MPs to vote for prime ministers representing the party they had campaigned for. Such changes facilitate the relatively long time Michael Somare was prime minister. However, in 2010 these laws and related constitutional changes were deemed unconstitutional. The other prime minister with a long time in office, Peter O'Neill, had his position facilitated by constitutional changes restricting no confidence votes and reducing the parliamentary period. These changes were also later declared unconstitutional.[31][1]: 13 [12]: 83–84

Under a 2002 amendment, the leader of the party, who wins the largest number of seats in the election, is invited by the governor-general to form the government if they can muster the necessary majority in parliament.[citation needed] Forming such a coalition involves considerable negotiations between party leaders, both to create and maintain coalitions.[14]: 59

2022 parliamentary election results

Remove ads

Judicial branch

Summarize

Perspective

Papua New Guinea's judiciary is independent of the government. It protects constitutional rights and interprets the laws. There are several levels, culminating in the Supreme Court of Papua New Guinea.

There is a Supreme Court of Papua New Guinea, not separately constituted but an appellate Full Court of the National Court. Its chief justice, also the chief justice of the National Court, is appointed by the governor general on the proposal of the National Executive Council after consultation with the minister responsible for justice. Other justices of the National Court, who are available to sit as members of ad hoc benches of the supreme court, are appointed by the Judicial and Legal Services Commission.

Litigation has become common, increasing the cost of the judicial system.[15]: 211–212 Government infrastructure, including schools and airstrips, often lead to demands for compensation from local communities, impeding development and creating local tensions.[11]: 10 [26]: 320–321 [8]: 14 Media is generally free, but weak.[29]: 231–237 Of national newspapers, there are two national English language daily newspapers, two English language weekly ones, and one weekly Tok Pisin newspaper. There are some local television services, as well as both government-run and private radio stations.[29]: 227–228 There are 3 mobile carriers, although Digicel has a 92% market share due to its more extensive coverage of rural areas.[29]: 240 Around two-thirds of the population is thought to have some mobile access, if intermittent.[29]: 241

Remove ads

Provincial government

Summarize

Perspective

Reforms in June 1995 changed the provincial government system. Regional (at-large) members of Parliament became provincial governors, while retaining their national seats in Parliament.

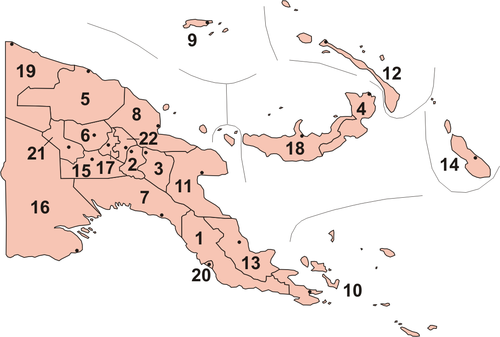

While Papua New Guinea is a unitary state, it is highly decentralised.[8]: 11 Papua New Guinea is divided into four regions. Although these are not the primary administrative divisions,[32] they are significant in many aspects of government,[33] commercial, sporting, and other activities.[citation needed] The nation has 22 province-level divisions: twenty provinces, the Autonomous Region of Bougainville and the National Capital District. Each province is divided into districts (with 89 overall), which in turn are divided into one or more Local-Level Government areas (LLGs). There are over 300 LLGs, which are divided between a small number of urban LLGs, and rural LLGs, which have slightly different governance structures.[34][35] The smallest province by size and population, Manus, has just one coterminous district.[36] Provinces[note 1] are the primary administrative divisions of the country, with provincial governments consisting of the national MPs elected from that province. Local governments exist parallel to traditional tribal leadership.[37] They are very dissimilar in population: the most populous six make up half of the national population, while the smallest six make up 14%.[38]: 31 Provinces can levy their own taxes, and have some control over education, health, and development.[39]: 15 The province-level divisions are as follows:

|

North Solomons (Bougainville)

On Bougainville Island, initially focused on traditional land rights, environmental and economic issues stemming from the operation of the Panguna mine, (a Conzinc RioTinto Australia (now Rio Tinto Limited) and PNG government joint venture), a civil war quickly grew into a war for independence from PNG.

From early 1989 until a truce came into effect in October 1997 and a permanent cease-fire was signed in April 1998 as many as 20,000 people were killed. Under the eyes of a regional peace-monitoring force and a United Nations observer mission, the government and provincial leaders established an interim government. In 2019 a non-binding referendum was held in which 98.31% of voters voted in favor of independence.

The people of Bougainville are closely related to those of the nearby Solomon Islands.

Remove ads

Instability

Summarize

Perspective

The Morauta government brought in a series of electoral reforms in 2001, designed to address instability and corruption. Among the reforms was the introduction of the Limited Preferential Vote system (LPV), a modified version of Alternative vote, for future elections in PNG. (The introduction of LPV was partly in response to calls for changes in the voting system by Transparency International and the European Union.) The first general election to use LPV was held in 2007.

There are many parties, but party allegiances are weak. Winning candidates are usually courted in efforts to forge the majority needed to form a government, and allegiances are fluid. No single party has yet won enough seats to form a government in its own right.[40]

Papua New Guinea has a history of changes in government coalitions and leadership from within Parliament during the five-year intervals between national elections. New governments are protected by law from votes of no confidence for the first 18 months of their incumbency, and no votes of no confidence may be moved in the 12 months preceding a national election.

On Bougainville Island, a rebellion occurred from early 1989 until a truce came into effect in October 1997 and a permanent cease-fire was signed in April 1998. Under the eyes of a regional peace-monitoring force and a United Nations observer mission, the government and provincial leaders established an interim government and made efforts toward toward election of a provincial government and a referendum on independence, the latter of which occurred in 2019. Michael Somare was reelected Prime Minister, a position he also held in the country's first parliament after independence, in 2002, where he won amidst violence-marred polling. Supplementary elections were held in Southern Highlands province in June 2003 after record levels of electoral fraud and intimidation during the 2002 polls.

A study by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, entitled "Strengthening our neighbour: Australia and the future of Papua New Guinea" and published in December 2004 found that PNG's weak government and policing has allowed organized crime gangs to relocate from Southeast Asia in recent years.

Remove ads

2011–12 political crisis

From 2011 to 2012, there was a constitutional dispute between parliament and Peter O'Neill and the judiciary, governor-general and Sir Michael Somare. The crisis involved the status of the prime minister and who is the legitimate head of government between O'Neill and Somare.

After 2019

In May 2019, James Marape was appointed as the new prime minister, after a tumultuous few months in the country’s political life. Marape was a key minister in his predecessor Peter O’Neill’s government, and his defection from the government to the opposition camp had finally led to O’Neill’s resignation from office.[41] In July 2022, Prime Minister James Marape's PANGU Party secured the most seats of any party in the election, meaning James Marape was elected to continue as PNG's Prime Minister.[42]

Remove ads

Foreign relations

Summarize

Perspective

Papua New Guinea has sought to maintain good relations with its neighbours Australia, Indonesia, and the Solomon Islands, while also building links to Asian countries to the north. Tensions sometimes emerge with Australia due to changes in aid, while regional conflicts have complicated relations with the Solomon Islands and Indonesia, due to the Bougainville conflict and the Papua conflict respectively. In 1986, Papua New Guinea became a founding member of the Melanesian Spearhead Group alongside the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu, and the three signed a formal cooperation agreement in 1988. A cooperation treaty was signed with Indonesia in 1986, and Australia in 1987.[11]: 14–15 [43]: 258–259

Papua New Guinea has provided support to Indonesia's control of neighbouring Western New Guinea,[44] the focus of the Papua conflict where numerous human rights violations have reportedly been committed by the Indonesian security forces.[45][46][47] Those living in communities near the border are able to cross it for customary purposes.[48]: 33 Australia remains linked to Papua New Guinea through institutional and cultural ties, and has remained the most consistent provider of foreign aid, as well as providing peacekeeping and security assistance. There are growing ties to China, mostly as a source of infrastructure investments.[22]: 12–13 The strategic position of the country, linking Southeast Asia to the Pacific, has increased geopolitical interest in the 21st century.[49]

Papua New Guinea has been an observer state in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) since 1976,[22]: 18 [50] followed later by special observer status in 1981.[51] It has filed its application for full membership status.[52] Papua New Guinea is a member of the Non-Aligned Movement,[43]: 258–259 the Commonwealth of Nations,[22]: 14 [53] the Pacific Community,[citation needed] the Pacific Islands Forum,[22]: 15 [54] APEC, and the United Nations.[22]: 5

Papua New Guinea has been a member of the Forum of Small States (FOSS) since the group's founding in 1992.[55][page needed] Papua New Guinea is part of the ACP forum associated with the European Union.[56][non-primary source needed]

International organization participation

ACP, APEC, AsDB, ASEAN (observer), C, CP, ESCAP, FAO, G-77, IBRD, ICAO, ICFTU, ICRM, IDA, IFAD, IFC, IFRCS, IHO, ILO, IMF, IMO, Intelsat, IFRCS, IMO, ICRM, Interpol, IOC, IOM (observer), ISO (correspondent), ITU, NAM, OPCW, SPF, Sparteca, SPC, UNCTAD, UNESCO, UNIDO, UN, UPU, WFTU, WHO, WIPO, WMO, WTrO

Remove ads

Military

Summarize

Perspective

The Papua New Guinea Defence Force is the military organisation responsible for the defence of Papua New Guinea. It consists of three wings.[57][page needed] Its primary role is internal security, although it also patrols the border with Indonesia and the country's exclusive economic zone.[58]: 238–239 The Land Element has seven units: the Royal Pacific Islands Regiment, a special forces unit, a battalion of engineers, three other small units primarily dealing with signals and health, and a military academy. The Air Element consists of one aircraft squadron, which transports the other military wings. The Maritime Element consists of four Pacific-class patrol boats, three ex-Australian Balikpapan-class landing craft, and one Guardian-class patrol boat. One of the landing craft is used as a training ship. Three more Guardian-class patrol boats are under construction in Australia to replace the old Pacific-class vessels. The main tasks of the Maritime Element are to patrol inshore waters and to transport the Land Element. Because of its extensive coastline, Papua New Guinea has a very large exclusive economic zone. The Maritime Element relies heavily on satellite imagery to surveil the country's waters. Patrolling is generally ineffective because underfunding often leaves the patrol boats unserviceable. This problem will be partially corrected when the larger Guardian-class patrol boats enter service.

Remove ads

Law

Summarize

Perspective

The unicameral Parliament enacts legislation like in other Commonwealth realms that use the Westminster system of government. The cabinet collectively agrees on government policy, and then the relevant minister introduces bills to Parliament, depending on which government department is responsible for implementing a particular law. Backbench members of parliament can also introduce bills. Parliament debates bills (section 110.1 of the Constitution), which become enacted laws when the Speaker certifies that Parliament has passed them. There is no Royal assent.

All ordinary statutes enacted by Parliament must be consistent with the Constitution. The courts have jurisdiction to rule on the constitutionality of statutes, both in disputes before them and on a reference where there is no dispute but only an abstract question of law. Unusually among developing countries, the judicial branch of government in Papua New Guinea has remained remarkably independent, and successive executive governments have continued to respect its authority.

The "underlying law" (Papua New Guinea's common law) consists of principles and rules of common law and equity in English[59][non-primary source needed] common law as it stood on 16 September 1975 (the date of independence), and thereafter the decisions of PNG's own courts. The Constitution directs the courts and, latterly, the Underlying Law Act to take note of the "custom" of traditional communities. They are to determine which customs are common to the whole country and may also be declared to be part of the underlying law. In practice, this has proved difficult and has been largely neglected. Statutes are largely adapted from overseas jurisdictions, primarily Australia and England. Advocacy in the courts follows the adversarial pattern of other common-law countries. This national court system, used in towns and cities, is supported by a village court system in the more remote areas. The law underpinning the village courts is 'customary law'.

Remove ads

Crime and human rights

Summarize

Perspective

Papua New Guinea is considered to have one of the highest rates of violence against women in the world.[60][61] Such violence imposes both personal and communal costs, and is likely a reason why female participation in politics is the lowest in the region, and deters parents from sending their daughters to school.[62]: 167 A 2013 study found that 27% of men on Bougainville Island reported having raped a non-partner, while 14.1% reported having committed gang rape.[63] According to UNICEF, nearly half of reported rape victims are under 15 years old, and 13% are under 7 years old.[64] Former Parliamentarian Carol Kidu stated that 50% of those seeking medical help after rape are under 16, 25% are under 12, and 10% are under 8.[65] Under Dame Carol's term as Minister for Community Development, Parliament passed the Family Protection Act (2013) and the Lukautim Pikini Act (2015), although the Family Protection Regulation was not approved until 2017, delaying its application in the Courts.[66][failed verification] Changing views on violence being a normal part of relationships is a key part of efforts to decrease such violence.[67]

The 1971 Sorcery Act allowed for accusations of sorcery to act as a defence for murder until the act was repealed in 2013.[68] An estimated 50–150 alleged witches are killed each year in Papua New Guinea.[69] A Sorcery and Witchcraft Accusation Related National Action Plan was approved by the Government in 2015,[70] although funding and application has been deficient.[citation needed] Both men and women can be accused of sorcery, although in some areas it is more common for one gender to be accused. Accusations in Bougainville generally target men, while in the Highlands such accusations generally target women.[22]: 37–38 There are no protections given to LGBT citizens in the country.[citation needed] Homosexual acts are prohibited by law in Papua New Guinea.[71]

While tribal violence has long been a way of life in the highlands regions, an increase in firearms has led to greater loss of life. In the past, rival groups had been known to utilise axes, bush knives and traditional weapons, as well as respecting rules of engagement that prevented violence while hunting or at markets. These norms have been changing with a greater uptake of firearms. These are believed to be losses from government armouries,[72] as well as sourced from smuggling operations over the border into Indonesia.[23] Only 1/5th of 5000 Australian-made Self Loading Rifles[citation needed] and half of the 2000 M16s delivered to the PNGDF from the 1970s-1990s were found in government armouries during an audit in 2004 and 2005.[72] The smuggling and theft of ammunition have also increased violence in these regions. The police forces and military find it difficult to maintain control. Village massacres have increased with 69 villagers killed in a single attack in February 2024 in Enga Province.[73] Violence between raskol gangs occurs in both urban and rural areas, and some gangs have become linked to politicians. Raskol violence has had a marked impact on economic activity in rural areas.[62]: 167 While in the past traditional dispute resolution mechanisms may have reduced violence, these likely have not persisted into the modern economic and social system.[22]: 38

Papua New Guinea received a score of 5.6 out of 10 for safety from the state from the Human Rights Measurement Initiative.[74]

Royal PNG Constabulary

Summarize

Perspective

The Royal Papua New Guinea Constabulary is responsible for maintaining law and order. It has been challenged in this as more advanced weaponry exacerbates tribal conflicts, as well as being unable to prevent violence against women.[7]: 6 These challenges are compounded by underfunding, which has led to low morale. Issues have been raised regarding human rights abuses and destruction of property as a result of police actions.[62]: 168

The constabulary has been troubled in recent years by infighting, political interference and corruption. It was recognised from early after Independence (and hitherto) that a national police force alone could never have the capacity to administer law and order across the country, and that it would also require effective local-level systems of policing and enforcement, notably the village court magisterial service.[75][page needed] The weaknesses of police capacity, poor working conditions and recommendations to address them were the subject of the 2004 Royal PNG Constabulary Administrative Review to the Minister for Internal Security.[76] In 2011, Commissioner for Police Anthony Wagambie took the unusual step of asking the public to report police asking for payments for performing their duties.[77]

In September 2020, Minister for Police Bryan Jared Kramer launched a broadside on Facebook against his own police department, which was subsequently reported in the international media. In the post, Kramer accused the Royal PNG Constabulary of widespread corruption, claiming that "Senior officers based in Police Headquarters in Port Moresby were stealing from their own retired officers’ pension funds. They were implicated in organised crime, drug syndicates, smuggling firearms, stealing fuel, insurance scams, and even misusing police allowances. They misused tens of millions of kina allocated for police housing, resources, and welfare. We also uncovered many cases of senior officers facilitating the theft of Police land." Commissioner for Police David Manning, in a separate statement, said that his force included "criminals in uniform".[78][79]

Notes

- The Constitution of Papua New Guinea sets out the names of the 19 provinces at the time of Independence. Several provinces have changed their names; such changes are not strictly speaking official without a formal constitutional amendment, though "Oro," for example, is universally used in reference to that province.

See also

References

External links

Further reading

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads