Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

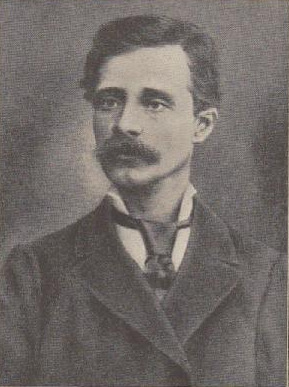

Grigor Parlichev

Bulgarian writer (1830–1893) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Grigor Stavrev Parlichev (Bulgarian: Григор Ставрев Пърличев; Macedonian: Григор Ставрев Прличев, romanized: Grigor Stavrev Prličev; 18 January 1830 – 25 January 1893), also known as Grigorios Stavridis (Greek: Γρηγόριος Σταυρίδης), was a Bulgarian writer, teacher and translator.[1][2][3] He received acclaim as a "second Homer" in Greece for his poem O Armatolos. Afterwards, he became a Bulgarian national activist. His other notable works include the poems Skenderbeg, 1762 leto, and his autobiographical work Autobiography. In North Macedonia and Bulgaria, he is regarded as a pioneer of national awakening, but his national identity has been also disputed between both countries.

Remove ads

Life

Summarize

Perspective

Grigor Parlichev was born on 18 January 1830 in Ohrid, Ottoman Empire (present-day North Macedonia), the fourth child of Maria Gyokova and Stavre Parlichev, a craftsman.[4] He was six months old when his father died. His paternal grandfather, a farmer, took over the care of the family. He was taught to read Greek by his grandfather. Parlichev studied in a Greek school in Ohrid.[5] He was taught by Dimitar Miladinov, a Bulgarian National Revival activist.[6] In 1839 or 1840, his grandfather died. His family lived in poverty. Parlichev's mother worked as a house servant, while he also contributed to the living of his family by selling goods at the market and copying Greek handwritings.[5] In 1848–1849, he was a teacher in a Greek school in Tirana, probably in Greek.[7] There, he experienced homesickness.[8] He went to Athens to study medicine in 1849 but lacking money to pay for his studies, he returned to Ohrid the following year.[9] In the 1850s, he worked as a teacher in Dolna Belica, Bitola, Prilep and Ohrid.[4] In this period, he was seen as a "Grecoman" by his contemporaries.[5] In 1858 Parlichev returned to Athens to study medicine in the second year, but later transferred to the Faculty of Linguistics.[5] Adopting the Hellenized form of his name, Grigorios Stavridis, in 1860 he took part in the annual poetry competition in Athens, winning first prize for his poem "O Armatolos" (Greek: Ο Αρματωλός), written in Greek.[10] Acclaimed as "second Homer" and given a bursary to study abroad, he gave part of it to a poor student and spent the rest of it.[6] Fellow contestant Theodoros Orphanidis accused him of being a Bulgarian and associated him with Bulgarian propaganda.[8] In 1862, he wrote another poem titled "Skenderbeg" (Greek: Σκενδέρμπεης) in Greek, with which he participated in the poetry competition, but it did not win an award.[11] After the death of his teacher Dimitar Miladinov in the same year, he returned to Ohrid.[12]

Upon his return, he became familiar with the Bulgarian language and the Cyrillic script.[11] Parlichev continued to teach Greek for a living. He encouraged the Bulgarians of Ohrid to send a petition to the Ottoman sultan for the restoration of the Archbishopric of Ohrid in May 1867.[9] In May 1868, he went to Istanbul (Constantinople) to study the Church Slavonic language.[11][6] After studying, he returned to Ohrid in November.[11] In the same year, he advocated for the use of Bulgarian in the schools and churches.[9] He also replaced Greek with Bulgarian in the Ohrid school where he was a teacher.[13] Parlichev was arrested and spent several months in an Ottoman jail in Debar after a complaint was sent by the Greek bishop of Ohrid Meletius due to his activities.[9]

He married Anastasiya Hristova Uzunova in 1869 and had five children: Konstantinka, Luisa, Kiril, Despina and Georgi.[4][5] In the 1870s, Marko Balabanov and the other editors of the magazine Chitalishte (Reading room) in Istanbul made him the suggestion to translate Homer's Iliad into Bulgarian.[11] In 1870 Parlichev translated his award-winning poem "O Armatolos" into Bulgarian in an attempt to popularize his earlier works, which were written in Greek, among the Bulgarian audience.[5] Parlichev was the first Bulgarian translator of Iliad in 1871.[10] However, he was criticized by Bulgarian literary critics because they considered his knowledge of Bulgarian as poor.[12] Parlichev used a specific mixture of Church Slavonic, Bulgarian, Russian and his native Ohrid dialect.[11] In 1872, he published the poem called 1762 leto.[4] He worked as a teacher in Gabrovo in 1879–1880 but he was not satisfied with the climate and the dialect there.[8] In 1883 Parlichev moved to Thessaloniki where he taught at the Thessaloniki Bulgarian Male High School from 1883 to 1889. During his stay there he wrote his autobiography between 1884 and 1885.[12][14] After his retirement in 1890, he returned to Ohrid, where he lived with a pension until his death on 25 January 1893.[9][5]

Identification and views

Per historian Raymond Detrez, who received his PhD for his thesis on Parlichev,[15] in his early life Parlichev was a member of the Romaic community, a multi-ethnic proto-nation, comprising all Orthodox Christians of the Ottoman Empire.[16] It had been under way until the 1830s, with the rise of nationalism in the Balkans. In his youth, he had no well-defined sense of national identity and developed a Greek (Rum Millet) identity (in the sense of being an Orthodox Christian), but as an adult, he adopted a Greek and later a Bulgarian national identity. In the last decade of his life, he adhered to a form of vague local Macedonian patriotism, though continued to identify himself as a Bulgarian. Thus, in the context of discussions about the existence of the Macedonian nation, his national identity became disputed between Bulgarian and Macedonian (literary) historians.[17] However, he never identified himself as an ethnic Macedonian.[18] As a Bulgarian national activist, he used German historian Jakob Fallmerayer's discontinuity thesis against the Greeks. In his autobiography, he wrote that the Bulgarians had been scorned and abused enough by other peoples and advised them to become aware of themselves, instead of despising themselves, to become confident of their abilities and rely on their hard work to achieve progress.[19] In 1889, under a translation, he signed himself as "Gr. S. Părličev, killed by the Bulgarians" (Гр. С. Пърличевъ, убитий българами).[5]

Language

As a child, Parlichev learned to write excellent Greek and later wrote in his autobiography that he mastered literary Greek better than a native speaker.[13] However, as an adult, despite his Bulgarian self-identification, Parlichev had poor knowledge of literary Bulgarian, which appeared to him as a "foreign language". He started learning to read and write in Bulgarian only after his return from Athens in 1862.[11] In his autobiography, Parlichev wrote: "I was, and I am still weak with the Bulgarian language,"[20][13] and "In Greek I sang like a swan, now in Slavic I cannot even sing like a donkey."[21] His native Ohrid dialect was different from the eastern Bulgarian dialects.[13] He used a mix of Church Slavonic, Russian and Bulgarian words and forms, as well as elements from his dialect, a mixture he called "common Slavic".[11] Because of this, he was criticized for his translation of Homer's Iliad.[22] Thus, according to Bulgarian historian Roumen Daskalov, Parlichev reacted against his Bulgarian literary critics by withdrawing into "an alternative Macedonian regional identity, a kind of Macedonian particularism."[19] However, when he came to write his autobiography, Parlichev used the standard Bulgarian language with some influence of his native Ohrid dialect.[23][24]

Legacy

His autobiography was published posthumously in Sofia in a Bulgarian periodical called Folklore and Ethnography Collection, produced by the Bulgarian Ministry of Education, in 1894.[6] Parlichev's son Kiril Parlichev became a prominent member of the revolutionary movement in Macedonia and a Bulgarian public figure.[12] After World War II, Macedonian historians started regarding him as an ethnic Macedonian author.[25] Both North Macedonia and Bulgaria regard him as a pioneer of national awakening.[12] The Parlichev Ridge in Antarctica is named after him.[26] A digital monument honoring him was set up in the center of Ohrid in 2022.[27][28]

Remove ads

See also

References

Further reading

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads