Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Hendra virus

Species of virus From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

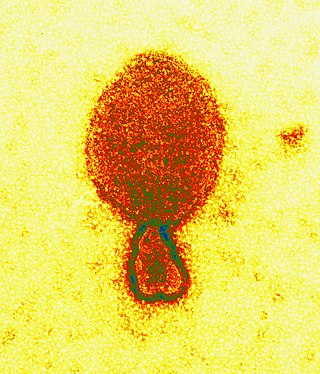

Hendra virus (Henipavirus hendraense) is a zoonotic virus found solely in Australia. First isolated in 1994, the virus has since been connected to numerous outbreaks of disease in domestic horses and seven human cases.[1] Hendra virus belongs to the genus Henipavirus, which also contains the zoonotic Nipah virus.[2] The reservoir species of Hendra virus are four species of bat within the genus Pteropus native to Australia.[3]

Remove ads

Pathology

The Pteropus fruit-eating bats, commonly known as flying foxes, experimentally infected with the Hendra virus develop a viraemia and shed the virus in their urine, faeces and saliva for approximately one week. There is no other indication of an illness in them.[4] Symptoms of Hendra virus infection of humans may be respiratory, including hemorrhage and edema of the lungs, or in some cases viral meningitis. In horses, infection usually causes one or more of pulmonary oedema, congestion and neurological signs.[5]

Ephrin B2 has been identified as the main receptor for the henipaviruses.[6]

Remove ads

Transmission

Flying foxes have been identified as the reservoir host of Hendra virus. A seroprevalence of 47% is found in the flying foxes, suggesting an endemic infection of the bat population throughout Australia.[7] Horses become infected with Hendra after exposure to bodily fluid from an infected flying fox. This often happens in the form of urine, feces, or masticated fruit covered in the flying fox's saliva when horses graze below roosting sites.[7]

In 2021 a new variant of Hendra virus named "Hendra virus genotype 2" (HeV-g2) was identified in two flying fox species in Australia.[8] It shares 84% sequence homology to other published Hendra virus genomes.[8] This variant has been identified in at least two horses that showed signs of Hendra virus infection.[9]

Remove ads

Prevention, detection and treatment

Summarize

Perspective

Three main approaches are currently followed to reduce the risk to humans.[10]

- Vaccine for horses.

- In November 2012, a vaccine became available for horses. The vaccine is to be used in horses only, since, according to CSIRO veterinary pathologist Deborah Middleton, breaking the transmission cycle from flying foxes to horses prevents it from passing to humans, as well as, "a vaccine for people would take many more years."[11][12]

- The vaccine is a subunit vaccine that neutralises Hendra virus and is composed of a soluble version of the G surface antigen on Hendra virus and has been successful in ferret models.[13][14][15]

- By December 2014, about 300000 doses had been administered to more than 100000 horses. About 3 in 1000 had reported incidents; the majority being localised swelling at the injection site. There had been no reported deaths.[16]

- In August 2015, the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA) registered the vaccine. In its statement the Australian government agency released all its data on reported side effects.[17] In January 2016, APVMA approved its use in pregnant mares.[18]

- Stall-side test to assist in diagnosing the disease in horses rapidly.

- Although the research on the Hendra virus detection is ongoing, a promising result has found using antibody-conjugated magnetic particles and quantum dots.[19][20]

- Post-exposure treatment for humans.

- Nipah virus and Hendra virus are closely related paramyxoviruses that emerged from bats during the 1990s to cause deadly outbreaks in humans and domesticated animals. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)-supported investigators developed vaccines for Nipah and Hendra virus based on the soluble G-glycoproteins of the viruses formulated with adjuvants. Both vaccines have been shown to induce strong neutralizing antibodies in different laboratory animals.

- Trials began in 2015 to evaluate a monoclonal antibody to be used as a possible complementary treatment for humans exposed to Hendra virus infected horses.[21]

- Deforestation Impact.

- When considering any zoonosis, one must understand the social, ecological, and biological contributions that may be facilitating this spillover. Hendra virus is believed to be partially seasonally related, and there is a suggested correlation between breeding time and an increase in the incidence of Hendra virus in flying fox bats.[22][23]

- Additionally, recent research suggests that the upsurge in deforestation within Australia may be leading to an increase in the incidence of Hendra virus. Flying fox bats tend to feed in trees during a large part of the year. However, due to the lack of specific fruit trees within the area, these bats are having to relocate and thereby are coming into contact with horses more often. The two most recent outbreaks of Hendra virus in 2011 and 2013 appear to be related to an increased level of nutritional stress among the bats as well as relocation of bat populations. Work is currently being done to increase vaccination among horses as well as replant these important forests as feeding grounds for the flying fox bats. Through these measures, the goal is to decrease the incidences of the highly fatal Hendra virus.[23]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

Emergence

Hendra virus (originally called "Equine morbillivirus") was discovered in September 1994 when it caused the deaths of thirteen horses, and a trainer at a training complex at 10 Williams Avenue, Hendra, a suburb of Brisbane in Queensland, Australia.[24][25]

The index case, a mare called Drama Series, brought in from a paddock in Cannon Hill, was housed with 19 other horses after falling ill, and died two days later. Subsequently, all of the horses became ill, with 13 dying. The remaining six animals were subsequently euthanised as a way of preventing relapsing infection and possible further transmission.[26] The trainer, Victory "Vic" Rail, and the stable foreman, Ray Unwin, were involved in nursing the index case, and both fell ill with an influenza-like illness within one week of the first horse's death. The stable hand recovered but Rail died of respiratory and kidney failure. The source of the virus was most likely frothy nasal discharge from the index case.[27]

A second outbreak occurred in August 1994 (chronologically preceding the first outbreak) in Mackay 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) north of Brisbane resulting in the deaths of two horses and their owner.[28] The owner assisted in necropsies of the horses, and within three weeks was admitted to hospital suffering from meningitis. He recovered, but 14 months later developed neurologic signs and died. This outbreak was diagnosed retrospectively by the presence of Hendra virus in the brain of the patient.[29]

Outbreak in Australia

As of June 2014, a total of fifty outbreaks of Hendra virus have occurred in Australia, all involving infection of horses. Since 1994, Hendra virus has been the cause of death in over 100 horses. Most cases have been the result of spillover infection from flying-foxes. Others have been the result of direct transmission from infected horses.[30]

Case fatality rate in humans is 60% and in horses 75%.[31]

Four of these outbreaks have spread to humans as a result of direct contact with infected horses. On 26 July 2011 a dog living on the Mt Alford property was reported to have HeV antibodies, the first time an animal other than a flying fox, horse, or human has tested positive outside an experimental situation.[32]

These events have all been on the east coast of Australia, with the most northern event at Cairns, Queensland and the event furthest south at Scone, New South Wales. Until the event at Chinchilla, Queensland in July 2011, all outbreak sites had been within the distribution of at least two of the four mainland flying foxes (fruit bats); Little red flying fox, (Pteropus scapulatus), black flying fox, (Pteropus alecto), grey-headed flying fox, (Pteropus poliocephalus) and spectacled flying fox, (Pteropus conspicillatus). Chinchilla is considered to be only within the range of little red flying fox and is west of the Great Dividing Range. This is the furthest west the infection has ever been identified in horses.[citation needed]

The timing of incidents indicates a seasonal pattern of outbreaks. Initially this was thought to possibly be related to the breeding cycle of the little red flying foxes. These species typically give birth between April and May.[33][34] Subsequently, however, the Spectacled flying fox and the Black flying fox have been identified as the species more likely to be involved in infection spillovers.[35]

Timing of outbreaks also appears more likely during the cooler months when it is possible the temperature and humidity are more favourable to the longer term survival of the virus in the environment.[36]

There is no evidence of transmission to humans directly from bats, and, as such it appears that human infection only occurs via an intermediate host, a horse.[37] Despite this in 2014 the NSW Government approved the destruction of flying fox colonies.[38]

Events of June–August 2011

This section needs to be updated. (July 2020) |

In the years 1994–2010, fourteen events were recorded. Between 20 June 2011 and 28 August 2011, a further seventeen events were identified, during which twenty-one horses died.[citation needed]

It is not clear why there was a sudden increase in the number of spillover events between June and August 2011. Typically HeV spillover events are more common between May and October. This time is sometimes called "Hendra Season",[115] which is a time when there are large numbers of fruit bats of all species congregated in SE Queensland's valuable winter foraging habitat. The weather (warm and humid) is favourable to the survival of henipavirus in the environment.[36]

It is possible flooding in SE Queensland and Northern NSW in December 2010 and January 2011 may have affected the health of the fruit bats. Urine sampling in flying fox camps indicate that a larger proportion of flying foxes than usual are shedding live virus. Biosecurity Queensland's ongoing surveillance usually shows 7% of the animals are shedding live virus. In June and July nearly 30% animals have been reported to be shedding live virus.[116] Present advice is that these events are not being driven by any mutation in HeV itself.[117]

Other suggestions include that an increase in testing has led to an increase in detection. As the actual mode of transmission between bats and horses has not been determined, it is not clear what, if any, factors can increase the chance of infection in horses.[118]

Following the confirmation of a dog with HeV antibodies, on 27 July 2011, the Queensland and NSW governments will boost research funding into the Hendra virus by $6 million to be spent by 2014–2015. This money will be used for research into ecological drivers of infection in the bats and the mechanism of virus transmission between bats and other species.[119][120] A further 6 million dollars was allocated by the federal government with the funds being split, half for human health investigations and half for animal health and biodiversity research.[121]

Remove ads

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads