Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Historical reliability of the Quran

Aspect of Islam From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The Quran is viewed to be the scriptural foundation of Islam and is believed by Muslims to have been sent down by Allah (God) and revealed to Muhammad by the angel Jibreel (Gabriel). Muslims have not used historical criticism in the study of the Quran, but they have used textual criticism in a similar way used by Christians and Jews.[1] It has been practiced primarily by secular, Western scholars such as John Wansbrough, Joseph Schacht, Patricia Crone, and Michael Cook, who set aside doctrines of the Quran's divinity, perfection, unchangeability, etc., accepted by Muslim scholars,[2] and instead investigate the Quran's origin, text, composition, and history.[2]

Scholars have identified several pre-existing sources for some Quranic narratives.[3] The Quran assumes its readers' familiarity with the Christian Bible and there are many parallels between the Bible and the Quran. Aside from the Bible, the Quran includes legendary narratives about Dhu al-Qarnayn, apocryphal gospels,[4] and Jewish legends.

Some philosophers and scholars such as Mohammed Arkoun, who emphasize the mythological content of the Quran, are met with rejectionist attitudes in Islamic circles.[5] In the Muslim world, scholarly criticism of the Quran can be considered an apostasy. Scholarly criticism of the Quran is thus a nascent field of study in the Islamic world.[6][7] Another -pretty new- interpretation of historical figures in the Qur'an is that the characters mentioned are not historical figures but certain typologies of evil people such as Nimrod (the king who humiliated and imprisoned Abraham), Haman, Qarun and Pharaoh, which we should understand as concepts related to human beings.[8]

Remove ads

Textual history

Summarize

Perspective

In Sunni tradition, it is believed that the first caliph Abu Bakr ordered Zayd ibn Thabit to compile the written Quran, relying upon both textual fragments and the memories of those who had memorized it during Muhammad's lifetime,[9] with the rasm (undotted Arabic text) being officially canonized under the third caliph Uthman ibn Affan (r. 644–656 CE),[10] leading the Quran as it exists today to be known as the Uthmanic codex.[11] Some Shia Muslims believe that the fourth caliph Ali ibn Abi Talib was the first to compile the Quran shortly after Muhammad died.[12]

The canonization process is believed to have been highly conservative,[13] although some amount of textual evolution is also indicated by the existence of codices like the Sanaa manuscript.[14][15] Beyond this, a group of researchers explores the irregularities and repetitions in the Quranic text in a way that refutes the traditional claim that it was preserved by memorization alongside writing. According to them, an oral period shaped the Quran as a text and order, and mentioned repetitions and irregularities were remnants of this period.[16]

Some Western scholars,[17] question the accuracy of the traditional accounts on whether the holy book existed in any form before the last decade of the seventh century (Patricia Crone and Michael Cook);[18] and/or argue it is a "cocktail of texts", some of which may have been existent a hundred years before Muhammad, that evolved (Gerd R. Puin),[18][19][20] or was redacted (J. Wansbrough),[21][22] to form the Quran.

It is also possible that the content of the Quran itself may provide data regarding the date and probably nearby geography of writing of the text. Sources based on some archaeological data give the construction date of Masjid al-Haram, an architectural work mentioned 16 times in the Quran, as 78 AH[23] an additional finding that sheds light on the evolutionary history of the Quranic texts mentioned,[24] which is known to continue even during the time of Hajjaj,[25][26][27] in a similar situation that can be seen with al-Aksa, though different suggestions have been put forward -contrary to some of the hadiths of Muhammad's ascension, which indicate that these places are architectural structures[28]- to explain.[Note 1] These structures, expected to be somewhere near Muhammad,[Note 2] which were placed in cities like Mecca and Jerusalem, which are thousands of kilometers apart today, with interpretations based on narrations and miracles, were only a night walk away according to the outward and literal meaning of the verse.Surah Al-Isra 17:1 (See also:Bakkah)

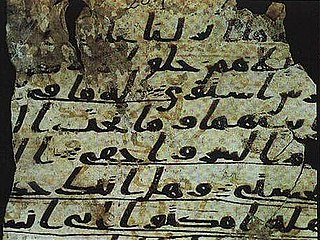

Early manuscripts

In the 1970s, 14,000 fragments of Quran were discovered in the Great Mosque of Sana'a, the Sana'a manuscripts. About 12,000 fragments belonged to 926 copies of the Quran, the other 2,000 were loose fragments. The oldest known copy of the Quran so far belongs to this collection. According to Sadeghi and Bergmann, the results indicated that the parchment had a 68% (1σ) probability of belonging to the period between 614 CE to 656 CE. It had a 95% (2σ) probability of belonging to the period between 578 CE and 669 CE. The carbon dating was applicable to the lower text. But paleography suggest a date from mid to latter half of the 7th century CE. Upper text dated between end of 7CE and beginning of the 8CE.

In 2015, a single of folio dating from between approximately AD 568 and 645, were identified at the University of Birmingham.[35] Islamic scholar Joseph E. B. Lumbard of Hamad Bin Khalifa University in Qatar has written in the Huffington Post in support of the dates proposed by the Birmingham scholars. Professor Lumbard notes that the discovery of a Qur'anic text that may be confirmed by radiocarbon dating as having been written in the first decades of the Islamic era, and includes variations in the “under text.” recorded in the Islamic historiographical tradition .[36] [unreliable source?]

Remove ads

Quran and History

Summarize

Perspective

Creation narrative

The Quran contains a creation narrative and may refer to the world being created in six days (yawm), although this is highly debatable. In Sūrah al-Anbiyāʼ, the Quran states that "the heavens and the earth were of one piece" before being parted.[37] God then created the landscape of the earth, placed the sky above it as a roof, and created the day and night cycles by appointing an orbit for both the sun and moon.[38] Some Muslim apologists, like Zakir Naik and Adnan Oktar advocate creationism and contemporary Islamic scholar Yasir Qadhi believes that the idea that humans evolved is against the Quran.[39] Most Muslims do not accept the theory of evolution, although there are substantial differences among countries (from <10% acceptance in Egypt to about 40% in Kazakhstan).[40] Some Muslims point to a verse in the Quran as evidence for Evolution “when He truly created you in stages ˹of development˺?” Verse 71:14. Evolution is taught in many Islamic countries, and some scholars have tried to reconcile the Quran and evolution.[41]

Around Moses

Qārūn

Korah is also mentioned in the Quran by the name of Qārūn (Arabic: قارون). He is recognized as wealthy, and became very arrogant due to his pride and ignorance.[42] He gave the credit for his wealth to his knowledge instead of to God.[43]

Indeed, Qarun was from the people of Moses, but he tyrannized them. And We gave him of treasures whose keys would burden a band of strong men; thereupon his people said to him, "Do not exult. Indeed, Allah does not like the exultant.

Haman

The name Haman, also appears in the biblical Book of Esther where Haman is a counselor of Ahasuerus, king of Persia and an enemy of the Jews. The relationship between the Biblical and Quranic Haman has been a topic of debate. There is no evidence of such stories in Egyptian history.[44] Some Islamic scholars compared plot elements of the book of Esther when they elaborated on the Quranic narrative of the Exodus.[45]

A Legendary Tower

The Quranic narrative brings together Moses, Pharaoh, Karun, Haman, and a tower made of mud bricks in the same story.[46] While some commentators, in an attempt to harmonize these elements from different geographical and historical periods, suggest that the structure in question could be a pyramid, the architecture of Egyptian pyramids does not resemble a tower, nor is the construction material made of clay, as the Quran describes. Another interpretation of the matter is that the characters mentioned are not historical figures, but rather specific typologies.[47]

Finally, Pharaoh's family found and took the child, who would become their enemy and a source of distress. Indeed, Pharaoh, his vizier Haman, and their soldiers were making a mistake. (Al-Qasas-8)

Pharaoh said, "I know of no god for you other than myself. O Haman, kindle a furnace for me in clay and build me a tower, perhaps I will ascend to the god of Moses, but I surely think he is one of those who lied." (Al-Qasas-38)

Samiri

Quran recounts a story of the golden calf, where it mentions that Samiri, a rebellious follower of Moses, created the calf while Moses was away for 40 days on Mount Sinai, receiving the Ten Commandments.[48] Due to the fact that as-Samiri can mean the Samaritan,[49] some believe that his character is a reference to the worship of the golden calves built by Jeroboam of Samaria, conflating the two idol-worshiping incidents into one.

Alexander the Great legends

Quran also employs popular legends about Alexander the Great called Dhul-Qarnayn ("he of the two horns") in the Quran. The story of Dhul-Qarnayn has its origins in legends of Alexander the Great current in the Middle East in the early years of the Christian era. According to these the Scythians, the descendants of Gog and Magog, once defeated one of Alexander's generals, upon which Alexander built a wall in the Caucasus Mountains to keep them out of civilised lands (the basic elements are found in Flavius Josephus).

The reasons behind the name "Two-Horned" are somewhat obscure: the scholar al-Tabari (839–923 CE) held it was because he went from one extremity ("horn") of the world to the other,[50] but it may ultimately derive from the image of Alexander wearing the horns of the ram-god Zeus-Ammon, as popularised on coins throughout the Hellenistic Near East.[51] The wall Dhul-Qarnayn builds on his northern journey may have reflected a distant knowledge of the Great Wall of China (the 12th century scholar al-Idrisi drew a map for Roger of Sicily showing the "Land of Gog and Magog" in Mongolia), or of various Sasanian Persian walls built in the Caspian area against the northern barbarians, or a conflation of the two.[52]

Dhul-Qarneyn also journeys to the western and eastern extremities ("qarns", tips) of the Earth.[53] In the west he finds the sun setting in a "muddy spring", equivalent to the "poisonous sea" which Alexander found in the Syriac legend. [54] In the Syriac original Alexander tested the sea by sending condemned prisoners into it, but the Quran changes this into a general administration of justice.[54] In the east both the Syrian legend and the Quran have Alexander/Dhul-Qarneyn find a people who live so close to the rising sun that they have no protection from its heat.[54]

"Qarn" also means "period" or "century", and the name Dhul-Qarnayn therefore has a symbolic meaning as "He of the Two Ages", the first being the mythological time when the wall is built and the second the age of the end of the world when Allah's shariah, the divine law, is removed and Gog and Magog are to be set loose.[55] Modern Islamic apocalyptic writers, holding to a literal reading, put forward various explanations for the absence of the wall from the modern world, some saying that Gog and Magog were the Mongols and that the wall is now gone, others that both the wall and Gog and Magog are present but invisible.[56]

Around Jesus

Death of Jesus

This section possibly contains original research. (July 2025) |

The Quran maintains that Jesus was not actually crucified and did not die on the cross. The general Islamic view supporting the denial of crucifixion was probably influenced by Manichaenism (Docetism), which holds that someone else was crucified instead of Jesus, while concluding that Jesus will return during the end-times.[58]

That they said (in boast), "We killed Christ Jesus the son of Mary, the Messenger of Allah";- but they killed him not, nor crucified him, but so it was made to appear to them, and those who differ therein are full of doubts, with no (certain) knowledge, but only conjecture to follow, for of a surety they killed him not:-

Nay, Allah raised him up unto Himself; and Allah is Exalted in Power, Wise;-

Despite these views, scholars maintain the historicity of the Crucifixion of Jesus.[60] The view that Jesus only appeared to be crucified and did not actually die predates Islam, and is found in several apocryphal gospels.[58]

Irenaeus in his book Against Heresies describes Gnostic beliefs that bear remarkable resemblance with the Islamic view:

He did not himself suffer death, but Simon, a certain man of Cyrene, being compelled, bore the cross in his stead; so that this latter being transfigured by him, that he might be thought to be Jesus, was crucified, through ignorance and error, while Jesus himself received the form of Simon, and, standing by, laughed at them. For since he was an incorporeal power, and the Nous (mind) of the unborn father, he transfigured himself as he pleased, and thus ascended to him who had sent him, deriding them, inasmuch as he could not be laid hold of, and was invisible to all.-

— Against Heresies, Book I, Chapter 24, Section 40

Irenaeus mentions this view again:

He appeared on earth as a man and performed miracles. Thus he himself did not suffer. Rather, a certain Simon of Cyrene was compelled to carry his cross for him. It was he who was ignorantly and erroneously crucified, being transfigured by him, so that he might be thought to be Jesus. Moreover, Jesus assumed the form of Simon, and stood by laughing at them.[61][62] Irenaeus, Against Heresies.[57]

Another Gnostic writing, found in the Nag Hammadi library, Second Treatise of the Great Seth has a similar view of Jesus' death:

I was not afflicted at all, yet I did not die in solid reality but in what appears, in order that I not be put to shame by them

and also:

Another, their father, was the one who drank the gall and the vinegar; it was not I. Another was the one who lifted up the cross on his shoulder, who was Simon. Another was the one on whom they put the crown of thorns. But I was rejoicing in the height over all the riches of the archons and the offspring of their error and their conceit, and I was laughing at their ignorance

Coptic Apocalypse of Peter, likewise, reveals the same views of Jesus' death:

I saw him (Jesus) seemingly being seized by them. And I said 'What do I see, O Lord? That it is you yourself whom they take, and that you are grasping me? Or who is this one, glad and laughing on the tree? And is it another one whose feet and hands they are striking?' The Savior said to me, 'He whom you saw on the tree, glad and laughing, this is the living Jesus. But this one into whose hands and feet they drive the nails is his fleshly part, which is the substitute being put to shame, the one who came into being in his likeness. But look at him and me.' But I, when I had looked, said 'Lord, no one is looking at you. Let us flee this place.' But he said to me, 'I have told you, 'Leave the blind alone!'. And you, see how they do not know what they are saying. For the son of their glory instead of my servant, they have put to shame.' And I saw someone about to approach us resembling him, even him who was laughing on the tree. And he was with a Holy Spirit, and he is the Savior. And there was a great, ineffable light around them, and the multitude of ineffable and invisible angels blessing them. And when I looked at him, the one who gives praise was revealed.

However, Islamic scholar Mahmoud M. Ayoub and historian of religion Gabriel Said Reynolds disagree with the mainstream interpretation of the Quranic narrative of Jesus' death, arguing that the Quran nowhere disputes that Jesus died.[63][64][further explanation needed]

Remove ads

See also

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads