Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

History of Somaliland

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

The history of Somaliland, an unrecognised country in the Horn of Africa, bordered by the Gulf of Aden, and the East African land mass, begins with human habitation tens of thousands of years ago. It includes the civilizations of Punt, the Ottomans, and colonial influences from Europe and the Middle East.

Islam was introduced to the area early on by the first Muslims of Mecca fleeing prosecution during the first Hejira with Masjid al-Qiblatayn in Zeila being built before the Qiblah towards Mecca. It is one of the oldest mosques in Africa.[1] In the late 9th century, Al-Yaqubi wrote that Muslims were living along the northern Somali seaboard.[2] Various Somali Muslim kingdoms were established in the area in the early Islamic period.[3] In the 14th to 15th centuries, the Zeila-based Adal Sultanate battled the Ethiopian Empire,[4] at one point bringing the three-quarters of Christian Abyssinia under the control of the Muslim empire under military leader Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi[5]

In the early modern period, successor states to the Adal Sultanate began to flourish in the region, including the Isaaq Sultanate led by the Guled dynasty.[6][7][8] The modern Guled Dynasty of the Isaaq Sultanate was established in the middle of the 18th century by Sultan Guled.[9] The Sultanate had a robust economy and trade was significant at the main port of Berbera but also eastwards along the coast, with the Isaaq controlling various trade routes into the port cities.[10][6][8]

In the late 19th century, the United Kingdom signed agreements with the Gurgure, Gadabuursi, Issa, Habr Awal, Garhajis, Habr Je'lo and Warsangeli clans establishing the Somaliland Protectorate,[11][12][13] which was formally granted independence by the United Kingdom as the State of Somaliland on 26 June 1960. Five days later, on 1 July 1960, the State of Somaliland voluntarily united with the Trust Territory of Somalia (the former Italian Somalia) to form the Somali Republic.[14][11]

The union of the two states proved problematic early on,[15] and in response to the harsh policies enacted by Somalia's Barre regime against the main clan family in Somaliland, the Isaaq, shortly after the conclusion of the disastrous Ogaden War,[16] a group of Isaaq businesspeople, students, former civil servants and former politicians founded the Somali National Movement (SNM) in London in 1981, leading to a 10 year war of independence that concluded in the declaration of Somaliland's independence in 1991.[17]

Remove ads

Prehistory

Summarize

Perspective

Somaliland has been inhabited since at least the Paleolithic. During the Stone Age, the Doian and Hargeisan cultures flourished.[18] The oldest evidence of burial customs in the Horn of Africa comes from cemeteries in Somalia dating back to the 4th millennium BC.[19] The stone implements from the Jalelo site in the north were also characterized in 1909 as important artefacts demonstrating the archaeological universality during the Paleolithic between the East and the West.[20]

According to linguists, the first Afro-Asiatic-speaking populations arrived in the region during the ensuing Neolithic period from the family's proposed urheimat ("original homeland") in the Nile Valley,[21] or the Near East.[22] Other scholars propose that the Afro-Asiatic family developed in situ in the Horn, with its speakers subsequently dispersing from there.[23]

The Laas Geel complex on the outskirts of Hargeisa in northwestern Somaliland dates back around 5,000 years, and has rock art depicting both wild animals and decorated cows.[24] Other cave paintings are found in the northern Dhambalin region, which feature one of the earliest known depictions of a hunter on horseback. The rock art is in the distinctive Ethiopian-Arabian style, dated to 1000 to 3000 BCE.[25][26] Additionally, between the towns of Las Khorey and El Ayo in eastern Somaliland lies Karinhegane, the site of numerous cave paintings of real and mythical animals. Each painting has an inscription below it, which collectively have been estimated to be around 2,500 years old.[27][28]

Remove ads

Antiquity

Summarize

Perspective

Land of Punt

Most scholars locate the ancient Land of Punt in the Horn of Africa between present-day Opone in Somaliland, Somalia, Djibouti, and Eritrea. This is based in part on the fact that the products of Punt, as depicted on the Queen Hatshepsut murals at Deir el-Bahri, were abundantly found in the region but were less common or sometimes absent in the Arabian Peninsula. These products included gold and aromatic resins such as myrrh, and ebony; the wild animals depicted in Punt include giraffes, baboons, hippopotami, and leopards. Says Richard Pankhurst : "[Punt] has been identified with territory on both the Arabian and the Horn of Africa coasts. Consideration of the articles which the Egyptians obtained from Punt, notably gold and ivory, suggests, however, that these were primarily of African origin. ... This leads us to suppose that the term Punt probably applied more to African than Arabian territory."[29][30][31][32] The inhabitants of Punt procured myrrh, spices, gold, ebony, short-horned cattle, ivory and frankincense which was coveted by the Ancient Egyptians. An Ancient Egyptian expedition sent to Punt by the 18th dynasty Queen Hatshepsut is recorded on the temple reliefs at Deir el-Bahari, during the reign of the Puntite King Parahu and Queen Ati.[33]

- Sculptures have the cobra emblem (uraeus) that is wedged in the personages headdress Discover in Berbera, Somaliland

Remove ads

Periplus

In the Classical era, the city states of Malao (Berbera) and Mundus ([Xiis/Heis) [See original map] prospered, and were deeply involved in the spice trade, selling myrrh and frankincense to The Romans and Egyptians Somaliland and Puntland became known as hubs for spices mainly cinnamon and the cities grew wealthy from it the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea tells us that the northern Somaliland and Puntland regions of modern-day Somalia were independent and competed with Aksum for trade.[34]

Early Islamic states

Summarize

Perspective

With the introduction of Islam in the 7th century in what are now the Afar-inhabited parts of Eritrea and Djibouti, the region began to assume a political character independent of Ethiopia. Three Islamic sultanates were founded in and around the area named Shewa (a Semitic-speaking sultanate in eastern Ethiopia, modern Shewa province and ruled by the Mahzumi dynasty, related to Muslim Amharas and Argobbas), Ifat (another Semitic-speaking[35] sultanate located in eastern Ethiopia in what is now eastern Shewa) and Adal and Mora (Gadabursi Clan, Somali, and Harari vassal sultanate of Ifat by 1288, centered on Dakkar and later Harar, with Zeila as its main port and second city, in eastern Ethiopia and in Somaliland's Awdal region; Mora was located in what is now the southern Afar Region of Ethiopia and was subservient to Adal).[citation needed]

At least by the reign of Emperor Amda Seyon I (r. 1314-1344) (and possibly as early as during the reign of Yekuno Amlak or Yagbe'u Seyon), these regions came under Ethiopian suzerainty. During the two centuries that it was under Ethiopian control, intermittent warfare broke out between Ifat (which the other sultanates were under, excepting Shewa, which had been incorporated into Ethiopia) and Ethiopia. In 1403 or 1415[36] (under Emperor Dawit I or Emperor Yeshaq I, respectively), a revolt of Ifat was put down during which the Walashma ruler, Sa'ad ad-Din II, was captured and executed in Zeila, which was sacked. After the war, the reigning king had his minstrels compose a song praising his victory, which contains the first written record of the word "Somali". Upon the return of Sa'ad ad-Din II's sons a few years later, the dynasty took the new title of "king of Adal," instead of the formerly dominant region, Ifat.[citation needed]

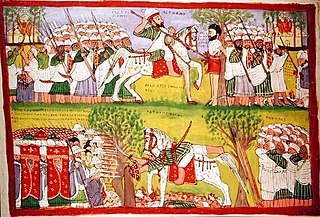

The area remained under Ethiopian control for another century or so. However, starting around 1527 under the charismatic leadership of Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrihim al-Ghazi (Gurey in Somali, Gragn in Amharic, both meaning "left-handed"), Adal revolted and invaded medieval Ethiopia. Regrouped Muslim armies with Ottoman support and arms marched into Ethiopia employing scorched earth tactics and slaughtered any Ethiopian that refused to convert from Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity to Islam.[37] Moreover, hundreds of churches were destroyed during the invasion, and an estimated 80% of the manuscripts in the country were destroyed in the process. Adal's use of firearms, still only rarely used in Ethiopia, allowed the conquest of well over half of Ethiopia, reaching as far north as Tigray. The complete conquest of Ethiopia was averted by the timely arrival of a Portuguese expedition led by Cristovão da Gama, son of the famed navigator Vasco da Gama. The Portuguese had been in the area earlier in early 16th centuries (in search of the legendary priest-king Prester John), and although a diplomatic mission from Portugal, led by Rodrigo de Lima, had failed to improve relations between the countries, they responded to the Ethiopian pleas for help and sent a military expedition to their fellow Christians. a Portuguese fleet under the command of Estêvão da Gama was sent from India and arrived at Massawa in February 1541. Here he received an ambassador from the Emperor beseeching him to send help against the Muslims, and in July following a force of 400 musketeers, under the command of Christovão da Gama, younger brother of the admiral, marched into the interior, and being joined by Ethiopian troops they were at first successful against the Somalis but they were subsequently defeated at the Battle of Wofla (28 August 1542), and their commander captured and executed. On February 21, 1543, however, a joint Portuguese-Ethiopian force defeated the Somali-Ottoman army at the Battle of Wayna Daga, in which al-Ghazi was killed and the war won.[citation needed]

Ahmed al-Ghazi's widow married Nur ibn Mujahid in return for his promise to avenge Ahmed's death, who succeeded Imam Ahmad, and continued hostilities against his northern adversaries until he killed the Ethiopian Emperor in his second invasion of Ethiopia, Emir Nur died in 1567. The Portuguese, meanwhile, tried to conquer Mogadishu but according to Duarta Barbosa never succeeded in taking it.[38] The Sultanate of Adal disintegrated into small independent states, many of which were ruled by Somali chiefs.[citation needed]

Remove ads

Early modern period

Summarize

Perspective

In the early modern period, successor states to the Adal Sultanate began to flourish in Somaliland, and by the 1600s the Somali lands split into numerous clan states, among them the Isaaq.[39] These successor states continued the tradition of castle-building and seaborne trade established by previous Somali empires.

These included the Isaaq Sultanate led by the Guled dynasty.[6][40] The Isaaq Sultanate was established in 1750 and was a Somali sultanate that ruled parts of the Horn of Africa during the 18th and 19th centuries.[6][40] It spanned the territories of the Isaaq clan, descendants of the Banu Hashim clan,[41] in modern-day Somaliland and Ethiopia. The sultanate was governed by the Rer Guled branch established by the first sultan, Sultan Guled Abdi, of the Eidagale clan.[42][43][44]

According to oral tradition, prior to the Guled dynasty the Isaaq clan-family were ruled by a dynasty of the Tolje'lo branch starting from, descendants of Ahmed nicknamed Tol Je'lo, the eldest son of Sheikh Ishaaq's Harari wife. There were eight Tolje'lo rulers in total who ruled for centuries starting from the 13th century.[45][46] The last Tolje'lo ruler Boqor Harun (Somali: Boqor Haaruun), nicknamed Dhuh Barar (Somali: Dhuux Baraar) was overthrown by a coalition of Isaaq clans. The once strong Tolje'lo clan were scattered and took refuge amongst the Habr Awal with whom they still mostly live.[47][48][49]

The modern Guled Dynasty of the Isaaq Sultanate was established in the middle of the 18th century by Sultan Guled of the Eidagale line of the Garhajis clan. His coronation took place after the victorious battle of Lafaruug in 1749 in which his father, a religious mullah Chief Abdi Chief Eisa successfully led the Isaaq in battle and defeated the Absame tribes who were allied to Garaad Dhuh Barar near Berbera where a century earlier the Isaaq clan expanded into.[9] After witnessing his leadership and courage, the Isaaq chiefs recognized his father Abdi who refused the position instead relegating the title to his underage son Guled while the father acted as the regent until the son came of age. Guled was crowned the as the first Sultan of the Isaaq clan in July 1750.[50] Sultan Guled thus ruled the Isaaq up until his death in 1808.[51]

After the death of Sultan Guled a dispute arose as to which of his 12 sons would succeed him. His eldest son Roble Guled, who was due to be crowned, was advised by his brother Du'ale to raid and capture livestock belonging to the Ogaden so as to serve the Isaaq sultans and dignitaries who would attend, as part of a plot to discredit the would-be sultan and usurp the throne. After the dignitaries were made aware of this fact by Du'ale they removed Roble from the line of succession and offered to crown Jama, his half brother, who promptly rejected the offer and suggested that Farah, Du'ale's full brother of Du'ale, son of Guled's fourth wife Ambaro Me'ad Gadidbe, be crowned.[51] The Isaaq subsequently crowned Farah,[52][51]

Early European Conflict

One of the most important settlements of the Sultanate was the city of Berbera which was one of the key ports of the Gulf of Aden. Caravans would pass through Hargeisa and the Sultan would collect tribute and taxes from traders before they would be allowed to continue onwards to the coast. Following a massive conflict between the Ayal Ahmed and Ayal Yunis branches of the Habr Awal over who would control Berbera in the mid-1840s, Sultan Farah brought both subclans before a holy relic from the tomb of Aw Barkhadle. An item that is said to have belonged to Bilal Ibn Rabah.

When any grave question arises affecting the interests of the Isaakh tribe in general. On a paper yet carefully preserved in the tomb, and bearing the sign-manual of Belat [Bilal], the slave of one [of] the early khaleefehs, fresh oaths of lasting friendship and lasting alliances are made...In the season of 1846 this relic was brought to Berbera in charge of the Haber Gerhajis, and on it the rival tribes of Aial Ahmed and Aial Yunus swore to bury all animosity and live as brethren.[53]

With the new European incursion into the Gulf of Aden and Horn of Africa contact between Somalis and Europeans on African soil would happen again for the first time since the Ethiopian–Adal war.[54] When a British vessel named the Mary Anne attempted to dock in Berbera's port in 1825 it was attacked and multiple members of the crew were massacred by the Habr Awal. In response the Royal Navy enforced a blockade and some accounts narrate a bombardment of the city.[55][6] In 1827 two years later the British arrived and extended an offer to relieve the blockade which had halted Berbera's lucrative trade in exchange for indemnity. Following this initial suggestion the Battle of Berbera 1827 would break out.[56][6] After the Isaaq defeat, 15,000 Spanish dollars was to be paid by the Isaaq Sultanate leaders for the destruction of the ship and loss of life.[55] In the 1820s Sultan Farah Sultan Guled of the Isaaq Sultanate penned a letter to Sultan bin Saqr Al Qasimi of Ras Al Khaimah requesting military assistance and joint religious war against the British.[57] This would not materialize as Sultan Saqr was incapacitated by prior Persian Gulf campaign of 1819 and was unable to send aid to Berbera. Alongside their stronghold in the Persian Gulf & Gulf of Oman the Qasimi were very active both militarily and economically in the Gulf of Aden and were given to plunder and attack ships as far west as the Mocha on the Red Sea.[58] They had numerous commercial ties with the Somalis, leading vessels from Ras Al Khaimah and the Persian Gulf to regularly attend trade fairs in the large ports of Berbera and Zeila and were very familiar with the Isaaq Sultanate respectively.[59][60]

Remove ads

British Somaliland

Summarize

Perspective

The British Somaliland protectorate was initially ruled from British India (though later on by the Foreign Office and Colonial Office), and was to play the role of increasing the British Empire's control of the vital Bab-el-Mandeb strait which provided security to the Suez Canal and safety for the Empire's vital naval routes through the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden.

Resentment against the British authorities grew: Britain was seen as excessively profiting from the thriving coastal trading and farming occurring in the territory.[citation needed] Beginning in 1899, religious scholar Mohammed Abdullah Hassan began a campaign to wage a holy war.[61] Hassan raised an army united through the Islamic faith[62] and established the Dervish State, fighting Ethiopian, British, and Italian forces,[63] at first with conventional methods but switching to guerilla tactics after the first clash with the British.[61] The British launched four early expeditions against him, with the last one in 1904 ending in an indecisive British victory.[64] A peace agreement was reached in 1905, and lasted for three years.[61] British forces withdrew to the coast in 1909. In 1912 they raised a camel constabulary to defend the protectorate, but the Dervishes destroyed this in 1914.[64] In the First World War the new Ethiopian Emperor Iyasu V reversed the policy of his predecessor, Menelik II, and aided the Dervishes,[65] supplying them with weapons and financial aid. Germany sent Emil Kirsch, a mechanic, to assist the Dervish Forces as an armourer at Taleh[66] from 1916–1917,[64] and encouraged Ethiopia to aid the Dervishes while promising to recognise any territorial gains made by either of them.[67] The Ottoman Empire sent a letter to Hassan in 1917 assuring him of support and naming him "Emir of the Somali nation".[66] At the height of his power, Hassan led 6000 troops, and by November 1918 the British administration in Somaliland was spending its entire budget trying to stop Dervish activity. The Dervish state fell in February 1920 after a British campaign led by aerial bombing.[64]

In 1920, the British colonial administration exiled the chieftain of the Warsangali clan to the Seychelles, accusing him of supporting the rebellion led by Mohammed Abdullah Hassan (known as the "Mad Mullah"). He was pardoned in 1928 and subsequently reinstated as clan chief.[68]

In 1920, facing severe financial constraints after the defeat of Hassan’s movement, the British Somaliland authorities established a public corporation intended to attract private investment. In 1922, they imposed new taxes on Somalis, triggering an armed protest in Burao. The colonial administration's locally recruited Somali troops refused orders to suppress the revolt, leading to the replacement of the governor. The new governor abandoned the taxation plan and again attempted to promote private investment, but the effort failed and the corporation was dissolved by 1926. By the late 1920s, oil exploration was conducted near Burao, but no deposits were discovered. Attempts to develop agriculture and livestock production also proved unsuccessful.[68]

Educational initiatives advanced slowly: the British sought to introduce instruction in the Somali language, while many local notables demanded Arabic-based education, causing prolonged disagreement.[68]

When the Second World War began, Italy temporarily occupied British Somaliland in August 1940 but was driven out six months later by British forces during the Battle of Somaliland.[69]

- Aerial bombardment of Dervish forts in Taleh.

- Map of invasion route of the Italian conquest of British Somaliland in August 1940

- Buralleh (Buralli) Robleh, Sub-Inspector of Police of Zeila, and General Gordon, Governor of British Somaliland, in Zeila (1921).

Moves toward independence

In 1947, the entire budget for the administration of the British Somaliland protectorate was only £213,139.[70]

Due to the limited development of formal education, few indigenous politicians emerged in British Somaliland.[71] In 1947, a council was established to represent the principal clans and districts of the protectorate, aiming to ensure a balance of regional and communal interests.[72] The body had only limited advisory authority and served primarily as a channel of communication between the British colonial administration and local Somali leaders.[73] The council consisted of forty-eight members and was designed to reflect clan proportionality within the protectorate.[74]: 23–24

In November 1949, the United Nations General Assembly decided the post-war fate of the former Italian colonies, stipulating that Italian Somaliland should be recognized as an independent state within ten years of the adoption of the trusteeship agreement. Italian administration under the United Nations Trust Territory officially began on 1 April 1950, and the Trusteeship Agreement was promulgated on 7 December 1951.[75]: 46–47

The Haud region, corresponding to the northern part of today's Somali Region in Ethiopia, came under Italian control in 1935 and later under British military administration in 1941. Although it was initially considered for inclusion in a future independent Somalia, the area was instead transferred to Ethiopian sovereignty under the 1954 Anglo–Ethiopian Agreement.[75]: 52–54 The decision, made with no consultation of local Somalis, triggered formal petitions submitted to the Government of the United Kingdom in London and to the United Nations in New York City.[71] The protests included participation from Michael Mariano, a member of the Habr Je'lo clan and one of the few Somali Roman Catholics, who leveraged both London and UN-based advocacy to draw international attention.[76] In these campaigns, Mariano and others sought the treatment of the Haud issue at the United Nations, visiting London and the UN to press their case.[71] A minority of Guardians, Councilors, and clan leaders aligned with Mariano’s position, but the larger colonial and diplomatic responses downplayed their views.[74]

The transfer of territory to Ethiopia in 1954 became a significant catalyst for nationalist sentiment and the emergence of the independence movement in British Somaliland.[77] Following the decision, Somali representatives submitted petitions and sent delegations to both the Government of the United Kingdom in London and the United Nations Headquarters in New York City.[71] In 1956, the Government of the United Kingdom declared that it would not oppose a future political union between British Somaliland and the Trust Territory of Somaliland (former Italian Somaliland) should such a request be made by the people of the protectorate.[78][79]

Somali participation in the colonial administration expanded during the late 1950s, as more Somalis were appointed to replace European officials in local government positions.[80] In 1957, the British authorities began to consider the introduction of an electoral framework, but instead opted to establish a Legislative Council composed of appointed representatives rather than a full party-based system.[81] The council’s unofficial members were nominated by the Governor, reflecting major clans and regions of the protectorate.[72] The number of members is not consistently recorded across sources; a figure of twenty-four members is attested in later research.[74]: 25–26

In January 1959, the British government announced that it would support closer relations with the Italian-administered Trust Territory of Somalia if desired by the Somaliland Legislative Council.[82] The council was subsequently expanded in February to include new appointed and elected members under a limited franchise system, with urban voters restricted to adult males owning a house or a camel, while rural representatives were chosen through traditional clan assemblies.[83] In the elections that followed, the National United Front (NUF), supported mainly by the Habr Je'lo sub-clan of the Isaaq, won seven seats,[84] while the Somali National League (SNL), which had boycotted the election in protest of the restrictive electoral system,[85] secured only one seat, with four independents elected.[74]: 26–27 Although the franchise was narrow, even the urban elections effectively reflected clan affiliations rather than party platforms.[74]

In November 1959, elections were held for 33 of the 37 seats in the Legislative Council, following the constitutional framework established earlier that year. Under this arrangement, three ministers were to be appointed directly by the Government of the United Kingdom, while four were to be chosen from among the elected Somali members, in line with the recommendations of the constitutional conference.[72] The electoral system employed a first-past-the-post method, and voting eligibility was limited to a restricted franchise based on earlier regulations.[83] The Somali National League (SNL), supported mainly by Isaaq sub-clans other than the Habr Je'lo, won the majority of the elected seats, while the United Somali Party (USP), backed largely by non-Isaaq clans such as the eastern Dhulbahante and Warsangali and the western Issa and Gadabuursi, emerged as the primary opposition. The National United Front (NUF), primarily supported by the Habr Je'lo, obtained only limited representation.[86] Candidates from the Somali Youth League (SYL) also participated, forming a temporary alliance with the NUF, but their combined electoral support—though substantial—did not translate into proportional representation due to the first-past-the-post system. Ministerial appointments following the election were distributed between the SNL and USP in proportion to their legislative strength.[74]

Remove ads

State of Somaliland

Summarize

Perspective

In May 1960, the British Government stated that it would be prepared to grant independence to the then Somaliland protectorate. The Legislative Council of British Somaliland passed a resolution in April 1960 requesting independence. The legislative councils of the territory agreed to this proposal.[87]

In April 1960, leaders of the two territories met in Mogadishu and agreed to form a unitary state.[88] An elected president was to be head of state, and full executive powers would be exercised by a prime minister responsible to an elected National Assembly of 123 members representing the two territories.[89][71]

On 26 June 1960, the British Somaliland protectorate gained independence as the State of Somaliland before uniting five days later with the Trust Territory of Somalia to form the Somali Republic (Somalia) on 1 July 1960.[90]

The legislature appointed the speaker Hagi Bashir Ismail Yousuf as first President of the Somali National Assembly and, the same day, Aden Abdullah Osman Daar become President of the Somali Republic.

- Agreements and Exchanges of Letters between the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the Government of Somaliland in connexion with the Attainment of Independence by Somaliland[91]

- The Somaliland Protectorate Constitutional Conference, London, May 1960 in which it was decide that 26 June be the day of Independence, and so signed on 12 May 1960. Somaliland Delegation: Mohamed Haji Ibrahim Egal, Ahmed Haji Dualeh, Ali Garad Jama and Haji Ibrahim Nur. From the Colonial Office: Ian Macleod, D. B. Hall, H. C. F. Wilks (Secretary)

Remove ads

Union with the Trust Territory of Somaliland

Summarize

Perspective

On 1 July 1960, the State of Somaliland united with the Trust Territory of Somaliland (former Italian Somaliland) as planned, forming the Somali Republic.[92] The first president was Aden Abdullah Osman Daar of the Somali Youth League (SYL) and the Hawiye clan, while the first prime minister was Abdirashid Ali Shermarke of the Majeerteen clan. Among those from the former British Somaliland, the highest-ranking position was held by Ibrahim Egal of the Isaaq clan, who served as Minister of Defence.[74]: 113

In July 1961, a national referendum was held on the new Constitution of Somalia, which had been largely based on an Italian draft prepared during the trusteeship period.[93] The Italian influence in the drafting process caused resentment in the north, where many residents of the former British Somaliland felt marginalized.[94] The ruling Somali National League (SNL) in the north called for a boycott of the referendum, leading to very low participation. Only around 100,000 voters took part in the northern regions, and a majority of these votes were cast against the constitution.[94] However, on a national level, the constitution was overwhelmingly approved, with approximately 1.7 million votes in favor and about 180,000 opposed, according to official results.[95] The referendum thus confirmed the unification framework between the two territories despite widespread discontent in the north.[96]: 3–5

In December 1961, a coup attempt took place in the former British Somaliland, where rebel officers temporarily seized control of key northern towns before being quickly suppressed.[74]: 113 [97]

In the 1964 Somali parliamentary election, the Somali Youth League (SYL) won a parliamentary majority, gaining 69 of the 123 seats in the National Assembly of Somalia. Within three months after the election, seventeen opposition members defected to the ruling party, strengthening SYL’s dominance.[98] Aden Abdullah Osman Daar of the Hawiye clan was reappointed as president, while Abdirizak Haji Hussein of the Majeerteen clan replaced Abdirashid Ali Shermarke as prime minister.[99] Abdirizak Haji Hussein pursued administrative reforms and expanded cabinet representation for politicians from the former British Somaliland, increasing the number of northern ministers from two to five.[98]

Meanwhile, Ibrahim Egal of the Isaaq clan, a former cabinet member from the ex-British Somaliland, did not serve in the new government under Prime Minister Abdirizak Haji Hussein.[74]: 115 During this period, Egal developed a close political relationship with former prime minister Abdirashid Ali Shermarke, who would later become president of the Somali Republic.[100] In October 1966, Ibrahim Egal left the Somali National League (SNL), which had been the ruling party in the north, and joined the Somali Youth League (SYL) as part of his growing alliance with Shermarke.[101]

In June 1967, Abdirashid Ali Shermarke was elected president, and Ibrahim Egal—also from the Isaaq clan of the former British Somaliland—was appointed prime minister.[100] The Somali Youth League (SYL) again won the 1969 Somali parliamentary election, and both Shermarke and Egal continued to serve in their respective offices until 1969.[102]: 337–341

Meanwhile, Ibrahim Egal of the Isaaq clan, a former cabinet member from the ex-British Somaliland, did not serve in the new government under Prime Minister Abdirizak Haji Hussein.[74]: 115 During this period, Egal developed a close political relationship with former prime minister Abdirashid Ali Shermarke, who would later become president of the Somali Republic.[100] In October 1966, Ibrahim Egal left the Somali National League (SNL), which had been the ruling party in the north, and joined the Somali Youth League (SYL) as part of his growing alliance with Shermarke.[101]

In June 1967, Abdirashid Ali Shermarke was elected president, and Ibrahim Egal—also from the Isaaq clan of the former British Somaliland—was appointed prime minister.[100] The Somali Youth League (SYL) again won the 1969 Somali parliamentary election, and both Shermarke and Egal continued to serve in their respective offices until 1969.[102]: 337–341

Repression of the Isaaq clan under the authoritarian president and the move toward renewed independence

In October 1969, President Abdirashid Ali Shermarke was assassinated by one of his bodyguards during a visit to Las Anod, and shortly afterward, on October 21, the civilian government led by Prime Minister Ibrahim Egal was overthrown in a bloodless coup led by army officer Mohamed Siad Barre.[103][104] Prime Minister Egal and several cabinet ministers were arrested and detained without trial, remaining in custody until 1975 according to international reports.[105][106][107]

After a revolution in Ethiopia in 1974, the Somali government covertly supported anti-government forces among Somali populations in Ethiopia by facilitating arms delivery and logistical aid to the Western Somali Liberation Front (WSLF).[108] In 1977, large contingents of the Somali National Army crossed into Ethiopia, launching the Ogaden War.[109] Though both nations possessed limited military capacity, Somalia achieved initial successes, capturing key towns and supply routes within Ogaden.[110][111] In 1978, Ethiopia mounted a counteroffensive supported by the Soviet Union and deployed Cuban troops, turning the tide of war and driving Somali forces back.[112]

As part of the Ogaden War, President Mohamed Siad Barre provided military support to the Ogaden clan of Somalis living in Ethiopia, primarily by arming and financing elements of the Western Somali Liberation Front (WSLF).[113] However, Ogaden militias also clashed with the Isaaq clan in the former British Somaliland, exacerbating long-standing local rivalries and leading many Isaaq to denounce Barre’s regional policies.[113][74]: 122 In response, Barre—by then a consolidated dictator—launched systematic repression against the Isaaq population, including arbitrary arrests, torture, and the destruction of communities under the pretext of counterinsurgency.[114]: 13 [74]: 122

In April 1981, members of the Isaaq clan based in the United Kingdom and Saudi Arabia met in London and founded the Somali National Movement (SNM), a rebel organization that later became the nucleus of the Somaliland independence movement.[115]: 33–36 At the time of its creation, however, the SNM did not advocate for secession but rather opposed President Mohamed Siad Barre’s authoritarian rule.[96]: 3–5 [74]: 124

In the capital of the former British Somaliland, Hargeisa, members of a diaspora group who had returned to improve medical facilities—known as the Uffo or Hargeisa Hospital Group—became increasingly vocal in criticizing government corruption and human rights abuses.[116] Beginning in 1981, many members of this group were arrested and subjected to harsh interrogations by the National Security Service.[117] Student protests and public demonstrations erupted soon after, and government troops opened fire on demonstrators, killing several people and detaining hundreds.[118] In early 1982, a special National Security Court sentenced fourteen of the arrested activists to long prison terms ranging from eight to thirty years.[119] Following appeals from international organizations, including Amnesty International, the detainees were eventually released after years of imprisonment.[120][74]: 125

Around this time, the Somali government introduced a neighborhood responsibility system known as tabeleh Somalia, under which local leaders were required to monitor and report any anti-government activity or unauthorized travel within their groups.[74]: 125 The regime also arrested prominent Isaaq clan, including former foreign minister Umar Arteh Ghalib, on fabricated charges.[121][122] The government armed neighboring clans such as the Dhulbahante and Gadabuursi to incite conflict with the Isaaq and maintain control in the north.[74]: 125 In 1982, the Somali National Movement (SNM) relocated its base of operations to Ethiopia, following intensified crackdowns in the north.[123] In 1983, the SNM launched a successful raid on Mandera Prison near Berbera, freeing a number of political prisoners.[124] In retaliation, President Mohamed Siad Barre ordered indiscriminate bombings within a fifty-kilometer radius of Mandera, resulting in widespread civilian casualties and property destruction.[118][74]: 127 The government also confiscated livestock and disrupted local trade in retaliation against clans accused of aiding the SNM.[74]: 127

By 1988, both Ethiopia and Somalia were experiencing major anti-government movements that threatened their regimes. The two governments consequently signed an agreement to cease mutual support for each other's insurgent groups, forcing the SNM to abandon its bases in Ethiopia and face possible dissolution. In May 1988, seeking to revive its cause, the SNM entered the territory of the former British Somaliland and temporarily captured Burao and Hargeisa.[74]: 127 [125][126] The Somali government responded with indiscriminate aerial bombardments of SNM-held areas, resulting in an estimated 50,000 to 60,000 deaths, although figures vary. The event is referred to in present-day Somaliland as the Isaaq genocide. Approximately 400,000 residents fled to Hart Sheik in Ethiopia,[127][128] while another 400,000 were displaced within Somalia.[129] [130] As a result, much of the Isaaq population became openly hostile to the government, and support for the SNM increased.[74]: 128

In 1990, Garad Abdiqani Garad Jama, the leading elder of the Dhulbahante in the east, asked that his clan be admitted into cooperation with the Somali National Movement (SNM), but the SNM declined due to the clan’s prior alignment with President Mohamed Siad Barre and participation in hostilities against the Isaaq.[74]: 131 A ceasefire was nevertheless reached between the parties in the east.[74]: 132 Meanwhile, the SNM initiated dialogue with western clans including the Gadabuursi, holding preliminary talks at Oog between Burao and Las Anod on 2–8 February 1991 and later convening a wider conference at Berbera on 15–27 February 1991, where inter-clan ceasefires and commitments to continued reconciliation were agreed.[131][132]: 16–17 [123]

Remove ads

Declassified U.S. Intelligence (1950s–1990s)

Summarize

Perspective

Declassified documents from the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) offer unique insight into how U.S. intelligence agencies viewed Somaliland’s political trajectory from the colonial period through the end of the 20th century. These reports, released under the Freedom of Information Act, reveal that the CIA closely monitored nationalist movements in British Somaliland, the 1960 unification with Somalia, Cold War alignments, and the eventual collapse of the Somali Democratic Republic’s central government.[133]

In March 1960, a CIA bulletin noted growing nationalist pressure for British Somaliland to achieve independence and unite with the Trust Territory of Somalia. The Agency described the situation as “confused and explosive,” warning that rapid unification might lead to instability especially given Ethiopia’s concerns over Somali irredentism and the idea of a “Greater Somalia.” After the 1 July 1960 union, CIA reports documented early signs of regional friction, including a failed coup d'état attempt by northern officers in 1961.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, CIA analyses highlighted the north (Somaliland) as a strategic zone due to its military buildup, Soviet influence, and tensions with Ethiopia. During Siad Barre’s regime, CIA assessments tracked the growing unrest in the north, particularly among the Isaaq clan. A 1982 intelligence report warned that Barre’s rule was weakening and that his government faced serious internal rebellion, with the SNM gaining ground in the north.[134]

By 1988, CIA and U.S. Defense sources documented the devastating counterinsurgency campaign launched by Barre’s military in response to SNM offensives in Hargeisa and Burao. The bombings of civilian areas in Somaliland cities were noted, although detailed reports remain classified. Following the collapse of Barre’s government in 1991, CIA records show that the SNM declared the Somaliland Declaration of Independence, reclaiming its brief 1960 sovereignty.

While the international community did not recognize Somaliland, CIA documents acknowledged its relative stability compared to the south (Somalia). A 1992 U.S. intelligence memorandum even suggested that self-governing regions like Somaliland might offer a foundation for future Somali stability.[135]

These records portray Somaliland not only as a subject of foreign strategic interest, but as a consistent focal point in U.S. assessments of Horn of Africa dynamics during and after the Cold War.

Remove ads

Restoration of Sovereignty

Summarize

Perspective

Declaration of Independence

At the second national meeting of the Burao grand conference on 18 May 1991, the Somali National Movement Central Committee, with the support of a meeting of elders representing the major clans in the Northern Regions, declared the restoration of the Republic of Somaliland in the territory of the former British Somaliland protectorate and formed a government for the self-declared state.[137] This followed the collapse of the central government in Somalia in the Somali Civil War. However, the region's self-declared independence remains unrecognized by any country or international organization.[138][139]

Under the agreement, the SNM was to exercise interim governance over Somaliland for a two-year period.[140] On proclamation day, SNM Chairman Abdirahman Ahmed Ali Tuur was inaugurated as President of the self-declared Republic of Somaliland.[124][74]: 134

However, within the Dhulbahante clan, opinions regarding Somaliland’s independence were divided. Only those who supported separation from Somalia participated in the Burao conference.[74]: 134 While a segment of Dhulbahante elders attended the Burao meeting, others convened a parallel assembly in Bo'ame, viewing the invitation to Burao as an attempt to undermine clan unity.[141] Some analysts have also argued that, at the time of Somaliland’s reassertion of independence, the Somali National Movement (SNM) held overwhelming military dominance in the region, leaving non-Isaaq clans little choice but to acquiesce to its authority.[142][123][143]

The Somaliland government officially commemorates 18 May as the “Restoration of Sovereignty Day,” marking the 1991 declaration that re-established Somaliland’s self-governance. According to the official register of public holidays, the date is designated as “Somaliland Re-assertion of Independence, 18 May.”[144][145] Annual nationwide celebrations are held in major cities such as Hargeisa, Borama, and Burao, featuring parades and cultural events to commemorate the anniversary.[146] Meanwhile, the 26th of June is recognized as Somaliland’s original Independence Day, commemorating its brief sovereignty in 1960 before unification with Somalia.[145]

Within the Somali National Movement (SNM), two major factions emerged: one loyal to the president, mainly composed of administrative and political figures, and another referred to as the "Red Flag" (Somali: Calan Cas), which functioned as the military wing. Some sources note that the term “Red Flag” was originally used by the faction’s opponents rather than by the members themselves.[147][148] The "Red Flag" faction was led by Colonel Ibrahim Abdillahi Dhegaweyne, a senior SNM commander who represented the movement’s militarized wing.[149][150] Following independence, Dhegaweyne and his faction sought to retain control over the revenues of the port of Berbera, which was under their administration.[151][152][142]

In February 1992, the Somaliland government initiated a campaign to disarm militias, prompting armed backlash in the town of Burao. The ensuing conflict lasted approximately one week and resulted in roughly three hundred fatalities.[74]: 134 In the weeks that followed, the government attempted to nationalize the key port of Berbera, provoking opposition from the Issa Musa sub-clan of Habr Awal, which had significant economic interests tied to the port. Authorities then tried to deploy forces composed largely of the Sa'ad Musa sub-clan, but these troops refused to act. President Tuur subsequently ordered an intervention force primarily drawn from Habar Yoonis, setting off intermittent fighting that persisted for about six months. Ultimately, the anti-Tuur Issa Musa forces prevailed, and the government lost control of a major revenue source.[74]: 135 The conflict is framed in multiple analyses as a struggle for economic authority over Berbera’s port revenues and regional influence following the collapse of central Somali state control. Longstanding factional tensions within the SNM and rivalries among sub-clans, particularly between Issa Musa and Habar Yoonis, played a decisive role in shaping the conflict’s trajectory.[153][154]

In response, a dialogue was held in the capital between Somaliland’s ruling party and opposition leaders, during which an agreement was reached to place Berbera port under direct government control. However, the Issa Musa clan elders rejected the terms, arguing their clan would be treated unfairly. In September 1992, mediation by the Gadabuursi clan led to a peace accord in Berbera under which other strategic facilities, including Hargeisa airport and Zeila port, would fall under equitable government oversight.[154]: 65 [132]: 16–17, 34–38 Although prisoners’ return and compensation had not been finalized, these matters were addressed in the November 1992 Sheikh conference, which helped stabilize the agreement. Nevertheless, the series of conflicts dealt a serious blow to the government’s legitimacy.[155]: 9–10 [156][74]: 136

National Reconciliation Conference and the Presidency of Egal: Transition from Clan Governance to Government Institutions

By late 1992, President Tuur, having failed to consolidate full executive control, appealed to Somaliland’s clan elders to mediate the political impasse. Consequently, a elders’ council, or Guurti, convened in the town of Burao for what would become known as the National Reconciliation Conference. Approximately 150 elders were empowered to vote, alongside 700–1,000 additional participants, representing a broad constituency across Somaliland’s clans.[132]: 20, 50–52 Under the terms of the agreement, a House of Elders (Guurti) composed of clan-based seats was instituted, along with plans for a lower house of elected representatives (which would not materialize until 2005).[132] The clan allocation was set at 90 seats for Isaaq, 30 seats for Darod, and 30 seats collectively for Gadabuursi and Issa. Crucially, the Guurti operated by consensus and deliberation rather than majority voting; the conference extended over four months, with reports of proposals being withdrawn due to the chairman’s ill health and calls to resume discussion rather than resort to ballot voting.[157]: 28, 36 [132]

In May 1993, the Guurti elected Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal as president for a two-year term. Egal was chosen largely because he was viewed as a civilian figure unaffiliated with the Somali National Movement (SNM) or other military factions, and thus acceptable to rival groups seeking a neutral leader.[158]: 446 Contemporary reports also describe his election at the Borama Conference as the result of deliberations among 150 voting elders representing all major clans.[153] Other analyses emphasize that Egal’s presidency was part of a wider transition from SNM-led revolutionary rule to a civilian administration, formalized through the National Charter adopted at Borama.[155]: 9–10 However, some sources suggest that Egal’s appointment also reflected strong backing from the “Calan Cas” (Red Flag) military faction within the SNM, whose leaders sought stability under a president who could reconcile the movement’s internal divisions.[142][159][132]: 20–21

Following the Borama Conference, Somaliland’s Guurti (House of Elders) initially convened in Borama rather than in the capital, Hargeisa. Because the House of Representatives had not yet been established, a de facto system emerged in which executive authority operated from Hargeisa while legislative deliberations were held in Borama. Over time, however, the Guurti began to be perceived as increasingly aligned with the executive branch.[157]: 30 [96]: 19, 31

Despite the Borama Conference’s achievements, stability was not immediately restored. The Habar Yoonis clan, to which former president Abdirahman Ahmed Ali Tuur belonged, declined participation in government posts after failing to secure the presidency. Within the broader Isaaq clan, rival sub-clans held differing degrees of political and historical prominence, and the absence of reliable demographic data led Habar Yoonis leaders to believe their influence had been unfairly reduced. Subsequently, former President Abdirahman Ahmed Ali Tuur traveled to Mogadishu and expressed support for Somali reunification. In April 1994, he publicly opposed Somaliland’s separation during a press conference in Addis Ababa, declaring his commitment to national unity.[153] He later participated in political meetings in Mogadishu aimed at promoting reconciliation across Somalia.[160] According to reports, he also aligned himself with a southern faction opposing Somaliland’s secession following internal divisions in 1993–1994.[132]: 22, 54

In 1993, President Mohamed Haji Ibrahim Egal established the Berbera Port Authority (BPA) and placed it directly under the Office of the President, thereby preventing the diversion of port revenues to former SNM military factions.[142] He lowered customs duties at the port, which was primarily controlled by his own Habar Awal clan, and received substantial loans from Habar Awal businessmen. These funds were used to finance the government’s operations and to support the disarmament of remaining militias.[155]: 46–49 [161][158]: 448

Later in 1994, the arrival of Somaliland shilling banknotes—originally ordered under the previous administration—led to further tension when Egal introduced the currency under terms seen as favorable to the government. This move fueled public distrust, particularly among the Habar Yoonis clan, many of whose elders expressed support for renewed union with Somalia.[158]: 448 [162][142]

The Habar Yoonis clan, based around Hargeisa Airport, began collecting unauthorized usage fees from passengers and, in October 1994, seized the airport by force. Fighting also broke out in Burao after the government sought to take control of its main trading center. An estimated 85,000 residents fled from Burao and as many as 200,000 from Hargeisa, though other sources suggest lower figures.[74]: 143 [153][163][164]

Conflict also extended to Zeila Port and trade routes near the Djibouti border, where clashes occurred between local militias and government forces. Although clan-based mediation efforts were attempted, Egal insisted on a state-led approach to conflict resolution, which prolonged the negotiations.[74]: 143 [165][166]

In November 1994, government forces seized Hargeisa Airport by force, triggering heavy fighting in and around the city.[153] The clashes drew widespread criticism, leading to peace conferences held first in Gothenburg, Sweden, and later in London in April 1995.[115]: 96–102 Funding for these reconciliation efforts was provided largely by the Somaliland diaspora, which played a central role in organizing the meetings and facilitating dialogue.[132]: 23–25 [74]: 144

In 1995, President Egal’s term officially ended, but ongoing conflicts and instability made elections impossible. The legislature extended his mandate by 18 months, a decision that was met with strong criticism from opposition figures.[96]: 5–6, 19 [74]: 146 However, the recurrence of localised armed confrontations did not necessarily indicate a lack of leadership. Some researchers have argued that through managing these limited clan-based conflicts, the government gradually consolidated its authority and strengthened state institutions.[155]: 48–49 [167]: 77

In October 1995, a peace conference was held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, where the "Somaliland Peace Committee" was established to mediate between the government and opposition forces.[74]: 145 According to the Academy for Peace and Development, the meeting aimed to create a reconciliation mechanism capable of facilitating dialogue between different clans and political actors, thereby preventing renewed escalation of armed conflict.[132]: 23–25, 31–33 Although clan rivalries continued within Somaliland, an agreement to end hostilities between the prominent Habr Yunis and Habr Je'lo clans was reached in September 1996 at Beer.[74]: 151 [115]: 102–109

Meanwhile, President Egal, with the cooperation of the Guurti (House of Elders), organized another peace conference in Hargeisa in October 1996.[158]: 449 Although the government failed to secure the participation of the Habr Je'lo clan, it successfully brought representatives of the Habr Yunis clan to the table.[74]: 151 [96]: 6–7, 19–21 The meeting was generally considered successful, marking a shift in authority over conflict resolution from clan-based structures to formal government institutions.[158]: 449 [155]: 26–27 In the aftermath, several international organizations that had previously operated from Borama relocated to Hargeisa, the capital.[158]: 450 This administrative centralization contributed to Hargeisa’s growing political importance, while Borama’s economic and institutional significance gradually declined.[168]

In 1997, Somaliland adopted a provisional constitution that included provisions extending the Guurti’s (House of Elders) term to six years.[169] Section 58 of the constitution explicitly designates the Guurti’s term as six years.[170] (Despite this, the Guurti has never been re-elected, with its members’ mandates continuously extended, and by 2025 no new election had taken place.[114])

In July 1998, the state of Puntland was proclaimed in northeastern Somalia. During its formation conference in Garowe, leaders declared that their territory would include regions claimed by Somaliland, namely areas inhabited by Warsangeli and Dhulbahante clans, placing the two entities in a latent territorial dispute.[171] Puntland’s territorial claims created a continuing source of border and resource tensions with Somaliland, particularly over the contested Sool and Sanaag regions, which straddle clan boundaries.[172] These contested borderlands, including parts of eastern Togdheer, have since experienced shifting control and intermittent militarization involving the Dhulbahante and Warsangeli clans.[173]: 24–25, 50, 153–161

In 1999, the Somaliland government attempted to establish administrative and police centers in the eastern regions of Sanaag and Sool, leading to a potential conflict with neighboring Puntland. Both President Mohamed Haji Ibrahim Egal and the Puntland administration chose to resolve the issue through dialogue, and the territorial status of the disputed regions remained undefined.[174]: 167 During this period, Sool and Sanaag were characterized by quiet negotiations and localized mediation efforts that prevented escalation, even as both administrations sought to expand their authority.[171][173]: 24–25, 50, 153–161

In November 1999, during President Egal’s visit to Borama, a group of residents publicly voiced opposition to Somaliland’s independence, marking one of the few official demonstrations against secession in recent years.[174]: 167 At that time, segments of the population in the Awdal region expressed reservations about Somaliland’s independence, and political debate over the question of unity with Somalia remained active.[115]: 110–114 [96]: 6–8, 19

In January 2000, the port of Berbera in Somaliland began to be used for trade between Ethiopia and overseas partners, and road improvements from Berbera to the Ethiopian border commenced.[175][176] Around this time, Ethiopia was affected by famine, and about 100,000 tons of food were delivered through the port of Berbera for relief operations.[177][178] This led to expectations that Ethiopia might recognize Somaliland, but such recognition did not occur. Analysts note that the Ethiopian government was concerned that formal recognition of Somaliland might contribute to instability in Somalia and the wider region.[174][179] Since 2000, the Somaliland government has imposed restrictions on local administrations collecting taxes directly, increasing their financial dependence on the central government.[158]: 450 [132]: 20–21, 34–38 [180]

Since March 1999, peace conferences aiming to end Somalia’s civil war had been organized in Djibouti under the mediation of its president and the auspices of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD). In April 2000, as part of this process, a Djiboutian delegation attempted to visit Somaliland, but the Somaliland government denied them entry. In response, the Djiboutian government expelled Somaliland’s representative from Djibouti.[181][182] In August 2000, another Somali peace conference was held in Djibouti, leading to the formation of the Transitional National Government (TNG) of Somalia, with Abdiqasim Salad Hassan as interim president. Somaliland did not participate. Abdiqasim, who was born in the former British Somaliland, appointed Ali Khalif Galaydh of the Dhulbahante clan as prime minister and Ismail Mahmud Hurre of the Isaaq clan as foreign minister.[174]: 168 [183] However, several major warlords based in Mogadishu also refused to join the TNG at that time.[184]

In 2001, the British government proposed that the European Union issue a statement welcoming the constitutional referendum held in Somaliland, but the initiative failed, largely due to strong opposition from Italy.[174]: 171 [185][186]

In May 2001, the Somaliland government announced that Ethiopia had begun accepting Somaliland passports and that regular air services were operating between the two territories.[175][187][188]

On 31 May 2001, Somaliland held a constitutional referendum that explicitly affirmed Somaliland’s independence. On 5 June, the government announced that the constitution had been approved with a 97% majority. President Egal stated that “85% of Somaliland’s people supported separation from Somalia,” though analysts estimated that about 70% of the population were actually in favor, given that opponents of independence largely boycotted the vote.[174]: 165 [96]: 13, 18, 29 Although the constitution formally provided for an electoral system based on individual voting rather than clan representation, the voting process remained strongly influenced by clan affiliations.[189]: 10 [140]: 14, 53–65 However, some analysts argue that the adoption of the constitution—and the subsequent 2002 local elections—marked Somaliland’s transition from a system of elder-led consensus politics to a more democratic, electoral-based political order.[142][190][191]

In July 2001, thirty-six members of the Somaliland House of Representatives accused President Egal of corruption and demanded his resignation, but their attempt to remove him failed.[174]: 166 [192]

In 2002, Somaliland held its first local council elections, which were also the first direct elections in the country’s history.[193][194]

Third President Kahin

After the death of President Mohamed Haji Ibrahim Egal in May 2002, Vice President Dahir Riyale Kahin assumed office as acting president.[195] Kahin subsequently ran in the 2003 presidential election and won, marking the first direct presidential election in Somaliland’s history.[193][196] The election was regarded by international observers as free and fair.[158]: 452 At the beginning of his term, there were concerns that instability might arise because Kahin was not from the dominant Isaaq clan of Somaliland.[174]: 175 However, in later years, his presidency came to be viewed positively for demonstrating that non-Isaaq politicians could also attain the presidency. Kahin had previously served as a senior officer in the National Security Service (NSS) under former Somali dictator Siad Barre, and his decision to appoint former NSS colleagues as advisors and ministers drew criticism. His administration also faced condemnation for its restrictive policies, including the arrest of journalists who published articles critical of the president and his wife, under charges of “false reporting against the government.”[158]: 453

As of 2002, it was reported that about 70 percent of Somaliland’s national budget was allocated to salaries for the army and police forces. However, this heavy security spending was also understood as part of a policy to re-employ former clan militiamen who had fought during Somaliland’s independence war, and analysts noted that reducing this budget could have led to severe security deterioration.[174]: 162 [197]

In December 2003, sub-clans of the Dhulbahante clan engaged in armed clashes, and under the pretext of mediation, Puntland forces occupied the Dhulbahante-inhabited town of Las Anod in southeastern Somaliland.[198][199]

In 2005, Somaliland held elections for the House of Representatives, which were the country’s first direct parliamentary elections.[193][200] The number of representatives from the dominant Isaaq clan increased, while the representation of eastern clans such as the Dhulbahante and Warsangali decreased. The elections were generally assessed as free and fair, although reports indicated that isolated incidents of vote-buying and irregularities occurred.[189]: 10 [201]

In September 2007, internal power struggles within the Puntland administration led a militia supporting a Dhulbahante minister to occupy Las Anod while claiming to represent Somaliland forces. In October of the same year, Somaliland’s regular army advanced into the town and took control.[202][203] Since then, Las Anod remained under Somaliland’s control until 2023.[204][205]

In 2008, President Kahin postponed the presidential election.[189]: 11 According to later analysis, some observers interpreted this as an attempt by Kahin to cling to power.[193][206][207]

In December 2008, while piracy was spreading across the Somali coast, reports noted that Somaliland had organized a coastal guard to contain such activities, whereas Puntland had become a center for pirate operations.[208][209][210]

In October 2009, members of the Dhulbahante clan in southeastern Somaliland formed a militia known as SSC (Sool, Sanaag and Cayn) to oppose Somaliland’s authority. However, internal clan divisions weakened the group, and by 2011 it had effectively disbanded.[211][173]: 153–161

Fourth President Silanyo

In June 2010, Somaliland held its second direct presidential election, in which Ahmed Silanyo was elected.[212] The voter registration at the time was reported as 1,069,914, but by 2016 the biometric registration total stood at 873,331—suggesting that a substantial number of registrations in 2010 may have been fraudulent.[213]

In January 2012, the Dhulbahante clan declared the formation of a new militia polity, the Khatumo State. Initially aiming to be admitted into the nascent Federal Government of Somalia, Khatumo was unable to consolidate control over its claimed capital in Las Anod, and only its military wings dispersed across regions. In October 2017, Khatumo formally announced its reintegration back into Somaliland authority.[214] The 2017 Ainabo agreement is often cited as the instrument of reconciliation and reabsorption of Khatumo elements. [215]

In March 2012, the Somaliland authorities employed counter-terrorism police units to dissolve a peaceful protest.[216]

As of 2012, the World Bank estimated Somaliland’s per capita GDP at approximately US$347, ranking it as the fourth poorest economy globally. Approximately 70 percent of the labor force was engaged in pastoralism and related trade. Annual remittances from the diaspora were estimated at US$500 million.[217][218] The government’s official statistical abstract confirms a 2021 per capita GDP estimate of US$775.[219]

In 2015, President Silanyo reached the end of his initial term, but the upper house (Guurti) extended his mandate by nine months due to delays in voter registration, which ultimately resulted in a two-year extension.[193][220][221]

In May 2016, the United Arab Emirates-based port operator DP World signed a 30-year concession agreement to develop and manage the Port of Berbera.[222] The project was seen as strategically significant not only for Somaliland but also for landlocked Ethiopia, providing it an alternative trade route to the sea besides Djibouti.[223] The Somali Federal Government objected to the deal, arguing that it had been made without Mogadishu’s authorization.[224]

By September 2017, the BBC reported that inflation had accelerated in Somaliland, leading to the widespread use of mobile-based electronic payment systems for even small transactions. In one shop, electronic payments rose from 5% to over 40% in two years.[225] Earlier studies also showed that Somaliland had become one of the most cashless economies in Africa due to the growth of the ZAAD mobile-money system and the dominance of digital transactions in daily life.[226][227][228]

Fifth President Muse Bihi Abdi

In December 2017, Muse Bihi Abdi was elected as the fifth President of Somaliland.[229] The election followed a 2016 nationwide voter registration that used iris recognition technology, reported by international observers as the first such countrywide use in Africa and applied to a large share of the electorate.[230]

In January 2018, Somaliland forces seized Tukaraq, east of Las Anod, from Puntland after clashes, escalating tensions between the two sides.[231]

In January 2018, Somaliland’s House of Representatives passed a law addressing women’s rights by criminalising rape with severe penalties, a measure subsequently advanced through the legislative process that year; the enacted Rape and Sexual Offences Law (Law No. 78/2018) codified offences including rape, gang rape, child-related sexual crimes and sexual harassment, and specified sentencing ranges up to lengthy terms of imprisonment.[232][233]

In September 2020, the Government of Somaliland opened a representative office in Taipei, thereby establishing bilateral relations with the Republic of China (Taiwan).[234][235] The two sides had earlier agreed in July 2020 to establish reciprocal representative offices in their respective capitals.[236] Although Taiwan is not a member of the United Nations, it maintains diplomatic relations with several UN member states.[237] The recognition by Taiwan marked the first formal recognition of Somaliland by another government.[238] (However, as of 2025, no country other than Taiwan has officially recognized Somaliland.[239])

In May 2021, Somaliland held its second elections for the House of Representatives since 2005.[240][241]

In October 2021, the Somaliland government deported over 7,000 residents, including 2,400 individuals from Las Anod, who did not hold Somaliland nationality.[242][243][244]

In August 2022, Somaliland forces seized Bo'ame, a major base of Puntland in the Sool region; Puntland troops withdrew without counterattacking, allowing Somaliland to assert control over much of the surrounding area.[245][246][247][248]

In February 2023, a large-scale rebellion by the Dhulbahante clan broke out in Las Anod, a city in southeastern Somaliland’s Sool region. According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), more than 200,000 people were displaced internally within Somaliland, while tens of thousands fled to Ethiopia.[249] UNHCR later reported that over 100,000 Somalis had crossed into Ethiopia following the fighting in and around Las Anod, primarily women and children seeking refuge in Somali Regional State camps.[250] A fact sheet published by the U.S. Government in September 2023 estimated the total displacement from the Las Anod crisis at approximately 280,000 people, with continuing humanitarian needs and protection concerns in both Somaliland and Ethiopia.[251] The insurgents proclaimed themselves as the “SSC-Khatumo State,” and in October 2023, the Federal Government of Somalia recognized the SSC-Khatumo administration.[252]

In January 2024, a memorandum of understanding was signed between Somaliland and Ethiopia. Although the details were not made public, statements by both leaders suggested that the agreement might include provisions for granting the Ethiopian Navy access to Somaliland’s coastline and for Ethiopia’s potential recognition of Somaliland as a sovereign state. The United States, Turkey, and Egypt reaffirmed that the area in question remains under the sovereignty of the Federal Government of Somalia.[253]

Sixth President Abdirahman Mohamed Abdullahi

In November 2024, Abdirahman Mohamed Abdullahi Irro was elected president, resulting in a change of administration. He was inaugurated on 12 December of the same year.[254]

Remove ads

References

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads