Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Hunminjeongeum

1446 Korean document on Hangul From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

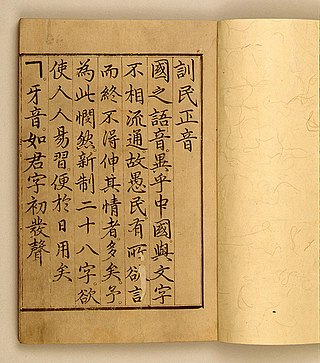

Hunminjeongeum[a] (Korean: 훈민정음[b]; Hanja: 訓民正音; lit. 'The Correct Sounds for the Instruction of the People'[1]) is a 1446 work that formally introduced the first native Korean alphabet. That alphabet was originally also called "Hunminjeongeum", although it is now widely called "Hangul" (international spelling; spelled in South Korea "Hangeul") or "Chosŏn'gŭl" (in North Korea).

The term Hunminjeongeum is used in a number of different ways, often due to the various editions and sections of the text. The term is sometimes used to refer to only the first two sections of the text: the preface and description of Hangul. That "base" Hunminjeongeum is sometimes referred to as the Yeui (예의; 例義). There is also a commentary section, the Hunminjeongeum Haerye, that was published alongside the base Hunminjeongeum. Sometimes, the base Hunminjeongeum and Haerye together are sometimes referred to only as Hunminjeongeum.

The base Hunminjeongeum was first published around October 1446 (Gregorian calendar) and authored by Joseon king Sejong the Great (r. 1418–1450). It was originally written in Classical Chinese using the Hanja script. It was later translated to the Korean language using Korean mixed script; such translated editions are called Eonhae (언해; 諺解; Ŏnhae). While the base Hunminjeongeum remained in the historical record, the Hunminjeongeum Haerye was lost and forgotten. It was only rediscovered in 1940.

The Hunminjeongeum and Haerye are considered to be among the most important works in the study of the Korean language. A copy of the full text, including the Haerye section, was designated a National Treasure of South Korea in 1962 and entered into the UNESCO Memory of the World Register in 1997.

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

Background

Before the invention of Hangul, Korea had been using Hanja (Chinese characters) since antiquity. The difficulty of the script limited its use to mostly upper-class people; commoners were largely illiterate. Hanja is not well suited for representing the Korean language; the Chinese and Korean languages are not closely related and differ in significant ways. For example, Classical Chinese uses subject–verb–object word order while Middle Korean uses subject–object–verb word order.[2]

Due to a lack of records, it is unknown when work on Hangul first began, nor what that process looked like. Joseon king Sejong the Great (r. 1418–1450) was responsible for and significantly involved in Hangul's creation.[3]

Hangul was first introduced, likely in a mostly complete form, to Sejong's court in the 12th month of 1443 of the Korean calendar (around December 30, 1443 to January 28, 1444 in the Gregorian calendar). Work then began on applying the script and developing official documentation for it; this would eventually culminate in the creation of the Hunminjeongeum and Haerye.[4]

Publication date

An exact publication date for the Hunminjeongeum and Haerye is not known. The base Hunminjeongeum claims to have been published in the 9th month of 1446 (Korean calendar). The postface to the Haerye is dated to the first ten days (상한; 上澣) of that month; it does not specify which day in that range the postface was completed. If the 10th day is assumed, that is October 9 in the Gregorian calendar; that day is celebrated as Hangul Day in South Korea.[5][6]

Remove ads

Content

Summarize

Perspective

The base Hunminjeongeum text was authored by Sejong and is composed of two parts: a brief preface and a description of the alphabet.[7] In the Hunminjeongeum Haerye edition, the base Hunminjeongeum consists of four leaves (sheets of paper).[8] The contents of the text are summarized below.

The preface is as follows:

The sounds of our country's language are different from those of the Middle Kingdom and are not confluent with the sounds of characters. Therefore, among the ignorant people, there have been many who, having something they want to put into words, have in the end been unable to express their feelings. I have been distressed because of this, and have newly designed twenty-eight letters, which I wish to have everyone practice at their ease and make convenient for their daily use.[9]

After the preface, the 28 letters are introduced. Each letter has their shape and brief description of their sound given using a Hanja character for reference. The 17 consonants are introduced first in the following order: ㄱ, ㅋ, ㆁ, ㄷ, ㅌ, ㄴ, ㅂ, ㅍ, ㅁ, ㅈ, ㅊ, ㅅ, ㆆ, ㅎ, ㅇ, ㄹ, ㅿ. Then the 11 vowels are introduced in this order: ㆍ, ㅡ, ㅣ, ㅗ, ㅏ, ㅜ, ㅓ, ㅛ, ㅑ, ㅠ, ㅕ.[10]

After the letters are introduced, these orthographic principles are given in the following order:[11]

- Initial consonants can also be used as terminal consonants.

- The light labial letters (연서; 連書; yŏnsŏ[12]) letters, ㅸ, ㆄ, ㅱ, and ㅹ, are introduced. These letters are formed by adding ㅇ directly underneath the labial consonants ㅂ, ㅍ, ㅁ, and ㅃ, and indicate lighter sounds.

- Initial and terminal consonants can be combined; when they are, they are written horizontally side-by-side.

- The vowels ㆍ, ㅡ, ㅗ, ㅜ, ㅛ, and ㅠ are written underneath the initial consonant, while ㅣ, ㅏ, ㅓ, ㅑ, and ㅕ are written just to the right of it. An initial consonant must always be paired with at least a vowel to form a syllable.

- Tone markings, called bangjeom or pangchŏm (방점; 傍點; lit. side dots), are placed to the left side of Hangul characters in a system called gajeom or kachŏm (가점; 加點):[13][14]

- Level tone (평성; 平聲) is indicated with no dots

- Departing tone (거성; 去聲) has a single dot ( 〮)

- Rising tone (상성; 上聲) has two dots ( 〯)

- Entering tone (입성; 入聲) does not receive its own dot indication. Pronunciation of characters in entering tone is quick and tense.

Remove ads

Versions and copies

Summarize

Perspective

There are various surviving pre-modern versions and copies of the text. Many of them were lost to the historical record and have been gradually rediscovered even into recent history.[15]

The extant versions of the text can be broadly categorized as follows:

- Yeui (예의; 例義; Yeŭi; 'Examples and Usages of the New Writing System'[16]): the base Hunminjeongeum by Sejong,[c] originally written in original Classical Chinese and Hanja.[7]

- Eonhae (언해; 諺解; Ŏnhae):[d] these are editions that have been translated to Korean and mixed script (Hangul and Hanja). All the extant Eonhae editions are translations of the Yeui. They are all likely to be related to and/or descended from the version in the Wŏrin sŏkpo.[18]

- Hunminjeongeum Haerye (훈민정음 해례; 訓民正音 諺解):[e] this is a modern term[f] used to refer to the edition of the Hunminjeongeum that contains both the Yeui and the commentary section on it, which is individually called Haerye. This version is in the original Classical Chinese and Hanja.[8]

Tone markings for Chinese (which appear as dots in corners of some cells[g]) vary between the copies and editions; they serve as an important tool for comparing and contrasting them.[20]

Hunminjeongeum Haerye

The Hunminjeongeum Haerye is believed to be closest to the original form of the text published in 1446. The Hunminjeongeum and Haerye are of separate authorship; the Haerye was written by a group of scholars led by Chŏng Inji.[8] While the Hunminjeongeum remained in the historical record, the Haerye was eventually lost and forgotten, possibly by the early 16th century. It was only rediscovered in 1940. This copy is referred to as the "Kansong copy".[22] This copy was designated a National Treasure of South Korea in 1962[23][24] and a UNESCO Memory of the World in 1997.[25][24][26]

A second copy, the Sangju copy, was discovered in 2008. However, its discoverer has refused to show it to others, even after the South Korean government was ruled the owner of the copy in 2019.[27]

Veritable Records of Sejong edition

One edition is included in the Veritable Records of Sejong, part of the Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty (also called sillok). It is in the original Hanja.[16][28][29] It contains the text of the Hunminjeongeum and excerpts of the Haerye, namely Chŏng's postface to it. There are some differences in the text of both Sejong's foreward and Chŏng Inji's preface with other editions. The excerpts of the Haerye were of particular historiographical importance until the rediscovery of the Haerye.[16]

Ahn argued that a copy of the Hunminjeongeum that appeared in a 1678 abridged copy of the text Paejayebuullyak seems to be based on the Veritable Records edition.[30]

Hunminjeongeum Eonhae

The Hunminjeongeum Eonhae edition contains the original Hanja text, annotations on that text, and a translation into Korean (using mixed script).[31] The oldest known variant of this edition was included as part of the opening chapter of the 1459 text Wŏrin sŏkpo, although it is unclear if this edition first appeared in that text. Wŏrin sŏkpo is likely a combination of two books originally published in the late 1440s: Wŏrin ch'ŏn'gangjigok and Sŏkposangjŏl. It is speculated that the inclusion of the Eonhae was possibly a practice adopted from Sŏkposangjŏl.[32] These editions have the title Sejong eoje hunminjeongeum (세종 어제 훈민정음; 世宗御製訓民正音; Sejong ŏje hunminjŏngŭm) written on them, where Sejong eoje means "authored by His Majesty Sejong".[33]

This edition contains some apparent additions, changes, and annotations that do not appear in the Haerye edition, which suggests that it was authored after that. For example, the Wŏrin sŏkpo version is the only version of the Hunminjeongeum to contain guidance on pure dental sibilants and palatal-supradental sibilants (치두음; 齒頭音 and 정치음; 正齒音),[h] which were used to transcribe Chinese. ᄼ, ᄽ, ᅎ, ᅏ, and ᅔ are the incisor-anteriors and ᄾ, ᄿ, ᅐ, ᅑ, and ᅕ are the incisor-palatals.[36][34]

The annotations explain meanings of the Chinese characters in the text, as well as further explanations of technical terminology.[37] The quality of the translation to Korean has also been scrutinized by modern scholars. Ahn argues that several alleged mistakes in translation are in fact efforts to deal with issues relating to Chinese tones.[38]

Various copies of this edition exist, with some minor variations in content and style.

- The oldest known copy, believed to be an original, was discovered in 1972 and became stored in Sogang University.[39] It is a Treasure of South Korea.[40]

- The first edition to be historiographically accounted for was a 1568 woodblock print originally at the temple Huibangsa.[39] The blocks were destroyed during the 1950–1953 Korean War.[41][42]

- An apparent copy of the Wŏrin sŏkpo edition was in the private collection of Pak Sŭngbin (1880–1943[43]) and later at Korea University, although that copy was apparently published separate from the rest of the Wŏrin sŏkpo. According to Ahn, scholars believe that changes in the text correspond not to 15th-century grammar but instead to the grammar of around King Sukjong's reign (r. 1661–1720).[44] It was held in high esteem until the rediscovery of the Haerye. The first page is missing and was replaced at some point.[45]

- One copy is in the collection of the Japanese Imperial Household Agency. Until the end of the first chapter, it is identical to the Pak Sŭngbin copy. It was possibly printed around the reigns of King Yeongjo (r. 1694–1776) or King Jeongjo (1776–1800).[46]

- One copy is in the private collection of the late Japanese linguist Shōzaburō Kanazawa. This copy appears identical to the original Wŏrin sŏkpo edition.[46]

Remove ads

Legacy

The Hunminjeongeum and Haerye are considered to be foundational works in the study of the Korean language.[47] A copy of the Haerye edition was designated a National Treasure of South Korea on December 20, 1962[23][24] and a UNESCO Memory of the World in 1997.[25]

Notes

- This is the Revised Romanization spelling used by UNESCO and the South Korean government. Also sometimes spelled Hunmin jeongeum (with a space). In the McCune–Reischauer romanization system, it is spelled Hunminjŏngŭm or Hunmin chŏngŭm.

- Spelling as given in the Hunminjeongeum Eonhae: 훈〮민져ᇰ〮ᅙᅳᆷ.

- I.e. Hunminjeongeum Eonhae or Hunminjeongeum Eonhaebon (언해본; 諺解本).

- Sometimes called Hunminjeongeum Haeryebon (훈민정음 해례본; 訓民正音諺解本)

Remove ads

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads